Trump admin dismisses Endangered Species List as “Hotel California”

“Once a species enters, they never leave,” interior secretary says. But there’s more to the story.

A female northern spotted owl catches a mouse on a stick at the Hoopa Valley Tribe on the Hoopa Valley Reservation on Aug. 28, 2024. Credit: The Washington Post/Getty Images

“You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.”

It’s the ominous slogan for “Hotel California,” an iconic fictional lodging dreamed up by the Eagles in 1976. One of the rock band’s lead singers, Don Henley, said in an interview that the song and place “can have a million interpretations.”

For US Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, what comes to mind is a key part of one of the country’s most central conservation laws.

“The Endangered Species List has become like the Hotel California: once a species enters, they never leave,” Burgum wrote in an April post on X. He’s referring to the roster of more than 1,600 species of imperiled plants and animals that receive protections from the federal government under the Endangered Species Act to prevent their extinctions. “In fact, 97 percent of species that are added to the endangered list remain there. This is because the status quo is focused on regulation more than innovation.”

US Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum speaks during a press conference on Aug. 11, 2025. Credit: Yasin Ozturk/Anadolu via Getty Images

Since January, the Endangered Species Act has been a frequent target of the Trump administration, which claims that the law’s strict regulations inhibit development and “energy domination.” Several recent executive orders direct the federal government to change ESA regulations in a way that could enable businesses—fossil fuel firms in particular—to bypass the typical environmental reviews associated with project approval.

More broadly, though, Burgum and other conservative politicians are implying the law is ineffective at achieving its main goal: recovering biodiversity. But a number of biologists, environmental groups and legal experts say that recovery delays for endangered species are not a result of the law itself.

Instead, they point to systemically low conservation funding and long-standing political flip-flopping as wildlife faces mounting threats from climate change and widespread habitat loss.

“We continue to wait until species are in dire straits before we protect them under the Endangered Species Act,” said David Wilcove, a professor of ecology, evolutionary biology, and public affairs at Princeton University, “and in doing that, we are more or less ensuring that it’s going to be very difficult to recover them and get them off the list.”

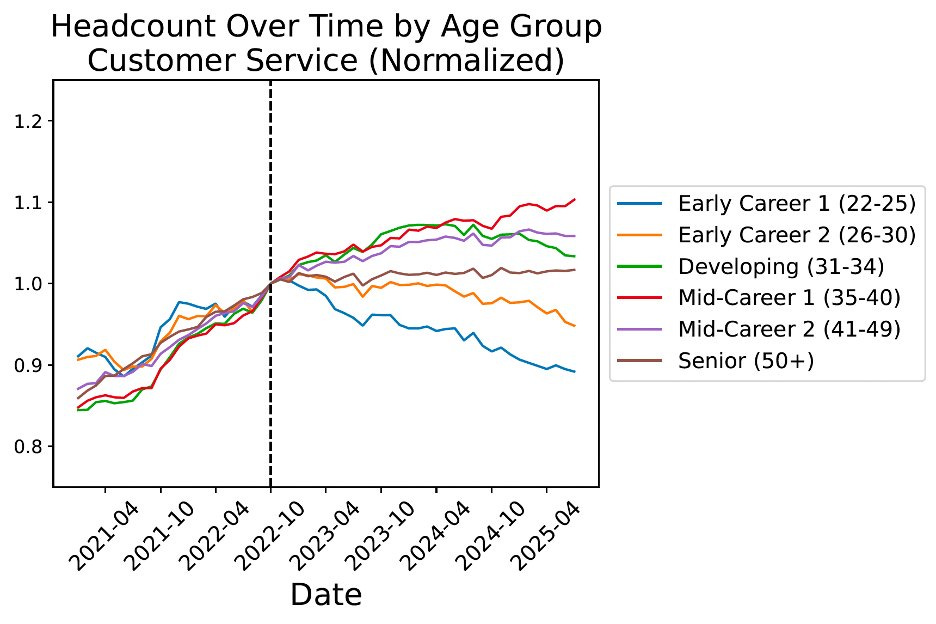

Endangered species by the numbers

Since the Endangered Species Act was enacted in 1973, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have listed more than 2,370 species of plants and animals as threatened or endangered—from schoolbus-sized North Atlantic right whales off the East Coast to tiny Oahu tree snails in Hawaii. In some cases, the list covers biodiversity abroad to prevent further harm from the global wildlife trade.

Once a plant or animal is added, it receives certain protections by the federal government to stanch population losses. Those measures include safeguards from adverse effects of federal activities, restrictions on hunting or development, and active conservation plans like seed planting or captive rearing of animals.

Despite these steps, only 54 of the several thousand species listed from 1973 to 2021 recovered to the point where they no longer needed protection. A number of factors play into this low recovery rate, according to a 2022 study.

The team of researchers who worked on it dove into the population sizes for species of concern, the timelines of their listings, and recovery efforts.

A few trends emerged: Most of the imperiled plants and animals in the US do not receive protections until their populations have fallen to “dangerously low levels,” with less genetic diversity and more vulnerability to extinction from extreme events like severe weather or disease outbreaks.

Additionally, the process to get a species listed frequently took several years, allowing time for populations to dip even lower, said Wilcove, a co-author of the study.

“It’s simply a biological fact that if you don’t start protecting a species until it’s down to a small number of individuals, you’re going to face a long uphill battle,” he said. On top of that, “there are more species in trouble, but at the same time, we are providing less funding on a per-species basis for the Fish and Wildlife Service, so we’re basically asking them to do more and more with less and less.”

These findings echo a similar paper Wilcove co-authored in 1993. Since that analysis was published, the number of listings has risen, while federal funding per species has dropped substantially. “Hotel California” isn’t the right analogy for the endangered species list, in Wilcove’s view: He says it’s more akin to “the critical care unit of the hospital”—one that is struggling to stay afloat.

“It’s as though you built a great hospital and then didn’t pay any money for medical equipment or doctors,” he said. “The hospital isn’t going to work.”

Even so, it has prevented a lot of deaths, experts say. Since the law was passed, just 26 listed species have gone extinct, many of which had not been seen in the wild for years prior to their listing. An estimated 47 species have perished while being considered for a listing, as they were still exposed to the threats that helped reduce their populations in the first place, according to an analysis by the High Country News. Some listing decisions take more than a decade.

“I think the marquee statistic is how few animals have gone extinct under the watch of the federal government,” said Andrew Mergen, the director of Harvard Law School’s Emmett Environmental Law and Policy Clinic. He spent more than 30 years serving as legal counsel in the US Department of Justice, where he litigated a bevy of cases related to the Endangered Species Act.

“Our goal should be to get them off the list and to recover them, but it requires a commitment to this enterprise that we don’t see very often,” Mergen said.

History shows it can be done. Bald eagles—widely considered an emblem of American patriotism—nearly disappeared in the 1960s, with just 417 known nesting pairs left in the lower 48 states. This was largely due to habitat loss and the pesticide DDT, which caused eagle eggshells to become too brittle to survive incubation. By the time the bald eagle was listed as threatened or endangered in all lower 48 states in 1978, DDT had been outlawed, a regulation that the ESA helped enforce, experts say.

A bald eagle flies over the Massapequa Preserve on March 25, 2025 in Massapequa, New York. Credit: Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

This step, along with captive breeding programs, reintroduction efforts, law enforcement, and habitat protection, helped recover populations to nearly 10,000 nesting pairs. In 2007, bald eagles came off the list. Other once-endangered animals like American alligators and Steller sea lions have also been delisted in recent decades due to targeted limits on actions that led to their decline, such as hunting.

Recovery gets trickier when threats to species are more multifaceted, according to Taal Levi, an associate professor at Oregon State University.

“The other class of species with complex, multicausal, or poorly understood threats can be like Hotel California,” Levi said over email. “This is in part because we don’t always have funding to research the threats, and if we identify them, we don’t always have funding to mitigate the threats.”

That is particularly true for the primary driver of biodiversity decline: habitat loss. Levi studies the endangered Humboldt marten, a small carnivore that lives on the Northern California and Southern Oregon coast. The animal was once widespread, but logging in old-growth and coniferous forests decimated their habitats. Now, Levi said it is difficult to fund research that helps unveil basic things about the animals, including what constitutes high-quality habitats. Other animals, like endangered Florida panthers, also struggle to maintain high populations in environments fragmented by urbanization.

“Sometimes being in Hotel California isn’t the worst thing,” Levi wrote in his email. “We’d prefer that Florida Panthers expand into other available habitat to the North of South Florida, but in lieu of that, maintaining them on the ESA seems wise to prevent their extinction.”

The private lands predicament

The federal government manages around 640 million acres of public lands and more than 3.4 million nautical miles of ocean, and it has final say on how endangered species are protected within these areas. However, more than two-thirds of species listed under the Endangered Species Act depend at least in part on private lands, with 10 percent residing only on such property.

The law prohibits any action that would harm a listed species wherever it might be, even if unintentionally. There is also a provision that enables the government to designate certain “critical habitat” areas that are crucial for a species’ survival, including on private land.

As a result, landowners and businesses often see endangered species as a detriment to their operations, said Jonathan Adler, an environmental law professor at William & Mary Law School in Virginia.

“Your ability to use that land is going to be limited, and you can be prosecuted… That creates a lot of conflict, and it discourages landowners from being cooperative,” he said. Adler published a paper in 2024 that argued the Endangered Species Act has been largely ineffective at conserving species, mainly due to the private land problem.

In some cases, this dynamic can create what Adler calls “perverse incentives” for landowners to destroy a habitat before a species is found on their land or listed to avoid any restrictions or costs associated with the endangered label.

Take the red-cockaded woodpecker, which typically relies on old-growth pine trees for nesting. This bird was part of the first cohort listed as endangered under the Act, which limited timber production in many areas of North Carolina. However, an analysis of timber harvests from 1984 to 1990 found that the closer a timber plot was to red-cockaded woodpeckers, the more likely the pines were to be harvested at a young age. This was most likely to prevent the trees from reaching maturity and avoid critical habitat regulation altogether, according to the 2007 study.

Adler argues that the ESA in its current form has too many sticks and not enough carrots. Over the years, Congress has implemented a few strategies to incentivize biodiversity protection on private lands, including providing tax benefits or purchasing conservation easements. This voluntary legal agreement allows an individual to receive compensation for a portion of their land while still owning it, in exchange for agreeing to certain restrictions, such as limiting development or following sustainable farming practices. Environmental groups often purchase conservation easements as well.

This strategy has helped protect animals like the California tiger salamander, San Joaquin kit fox, waterfowls, and other imperiled species. However, providing incentives to landowners for conservation is becoming less common under the Trump administration, Princeton’s Wilcove said.

The Department of the Interior did not respond to requests for comment.

“You shouldn’t reduce the prohibition on harming endangered species, but you should make it easier for landowners to do the right thing, and there are ways for doing that, and this administration is not a champion of those ways,” Wilcove said. “We’re waiting too long to protect species, and when we get around to protecting them, we’re not giving the government sufficient resources to do the job.”

Is the Endangered Species Act itself endangered?

The Endangered Species Act was passed with wide bipartisan support. But it has become one of the most highly litigated environmental laws in the US, in part because anyone can petition to have a species listed as endangered.

A number of conservative presidential administrations and members of Congress have tried to soften the law’s power, but more environmentally minded administrations often strengthened it once again.

“It’s been a very strong law, partly because so much of the public supports it,” said Kristen Boyles, an attorney at the nonprofit Earthjustice, which has frequently filed ESA-related lawsuits. “Whenever legislative changes have been proposed, we’ve pretty much been able to defeat those.”

But experts say things may be different this time around as the Trump administration takes a more accelerated and aggressive approach to the ESA at a time when environmentalists can’t count on the Supreme Court to push back.

Since January, the president has issued several executive orders that would allow certain fossil fuel projects to get a fast-pass trip through environmental reviews, including those that could harm endangered animals or plants. In April, the Fish and Wildlife Service proposed rescinding certain habitat protections for endangered species, effectively allowing such activities as logging and oil drilling even if they degrade the surrounding environment.

Meanwhile, the Department of the Interior and NOAA have in recent months cut funding for conservation programs and laid off many of the people responsible for carrying out the Endangered Species Act’s mandate. That includes rangers who were monitoring animals like the endangered Pacific fisher in California’s Yosemite National Park.

People observe North Atlantic right whales from a boat in Canada’s Bay of Fundy. Credit: (Photo by: Francois Gohier/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

“One thing that I would say to [Secretary Burgum] is that you have a duty to faithfully execute the law as a member of the executive branch as it was enacted by Congress,” Harvard’s Mergen said. “That’s going to mean that you should not cut all your biologists out but invest in the recovery of these species, understanding what’s putting them at risk and mitigating those harms.”

Conservation funding declined long before Trump entered office, so there is “plenty of blame to go around,” Wilcove said. But political flip-flopping on how recovery projects are carried out inhibit their effectiveness, he added. “If you’re lurching between administrations that care and administrations that are hostile, it’s going to be very hard to make progress.”

For all the discussion about the economic costs of endangered species regulations, studies show that funding biodiversity protection has a strong return on investment for society.

For instance, coastal mangroves around the world reduce property damage from storms by more than $65 billion annually and protect more than 15 million people, according to 2020 research. The Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that insect crop pollination equates to $34 billion in value each year.

Protecting vulnerable animals can also benefit industries that depend on healthy landscapes and oceans. Researchers estimated in 2007 that protecting water flow in the Rio Grande River in Texas for the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow produces average annual benefits of over $200,000 per year for west Texas agriculture and over $1 million for El Paso municipal and industrial water users.

Endangered species can be a boon for the outdoor tourism industry, too. NOAA Fisheries estimates that the endangered North Atlantic right whale generated $2.3 billion in sales in the whale-watching industry and across the broader economy in 2008 alone, compared to annual costs of about $30 million related to shipping and fishing restrictions protecting them.

Beyond financial gains, humanity has pulled a wealth of knowledge from nature to help treat and cure diseases. For example, the anti-cancer compound paclitaxel was originally extracted from the bark of the Pacific yew tree and is “too fiendishly complex” a chemical structure for researchers to have invented on their own, according to the federal government.

Preventing endangered species from going extinct ensures that we can someday still discover what we don’t yet know, according to Dave Owen, an environmental law professor at the University of California Law, San Francisco.

“Even seemingly simple species are extraordinarily complex; they contain an incredible variety of chemicals, microbes, and genetic adaptations, all of which we can learn from—but only if the species is still around,” he said over email.

Last month, the Fish and Wildlife Service announced that the Roanoke logperch—a freshwater fish—has recovered enough to be removed from the endangered species list altogether.

In a post on X, the Interior secretary declared this is “proof that the Endangered Species List is no longer Hotel California. Under the Trump admin, species can finally leave!”

But this striped fish’s recovery didn’t happen overnight. Federal agencies, local partners, landowners, and conservationists spent more than three decades, millions of dollars, and countless hours removing obsolete dams, restoring wetlands, and reintroducing fish populations to help pull the Roanoke logperch back from the brink. And it was the Biden administration that first proposed delisting the fish in 2024.

These types of success stories give reasons for hope, Wilcove said.

“What I’m optimistic about is our ability to save species, if we put our mind and our resources to it.”

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Trump admin dismisses Endangered Species List as “Hotel California” Read More »