On Friday’s launch, United Launch Alliance will test the limits of its Centaur upper stage.

United Launch Alliance’s second Vulcan rocket underwent a countdown dress rehearsal Tuesday. Credit: United Launch Alliance

The second flight of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan rocket, planned for Friday morning, has a primary goal of validating the launcher’s reliability for delivering critical US military satellites to orbit.

Tory Bruno, ULA’s chief executive, told reporters Wednesday that he is “supremely confident” the Vulcan rocket will succeed in accomplishing that objective. The Vulcan’s second test flight, known as Cert-2, follows a near-flawless debut launch of ULA’s new rocket on January 8.

“As I come up on Cert-2, I’m pretty darn confident I’m going to have a good day on Friday, knock on wood,” Bruno said. “These are very powerful, complicated machines.”

The Vulcan launcher, a replacement for ULA’s Atlas V and Delta IV rockets, is on contract to haul the majority of the US military’s most expensive national security satellites into orbit over the next several years. The Space Force is eager to certify Vulcan to launch these payloads, but military officials want to see two successful test flights before committing one of its satellites to flying on the new rocket.

If Friday’s test flight goes well, ULA is on track to launch at least one—and perhaps two—operational missions for the Space Force by the end of this year. The Space Force has already booked 25 launches on ULA’s Vulcan rocket for military payloads and spy satellites for the National Reconnaissance Office. Including the launch Friday, ULA has 70 Vulcan rockets in its backlog, mostly for the Space Force, the NRO, and Amazon’s Kuiper satellite broadband network.

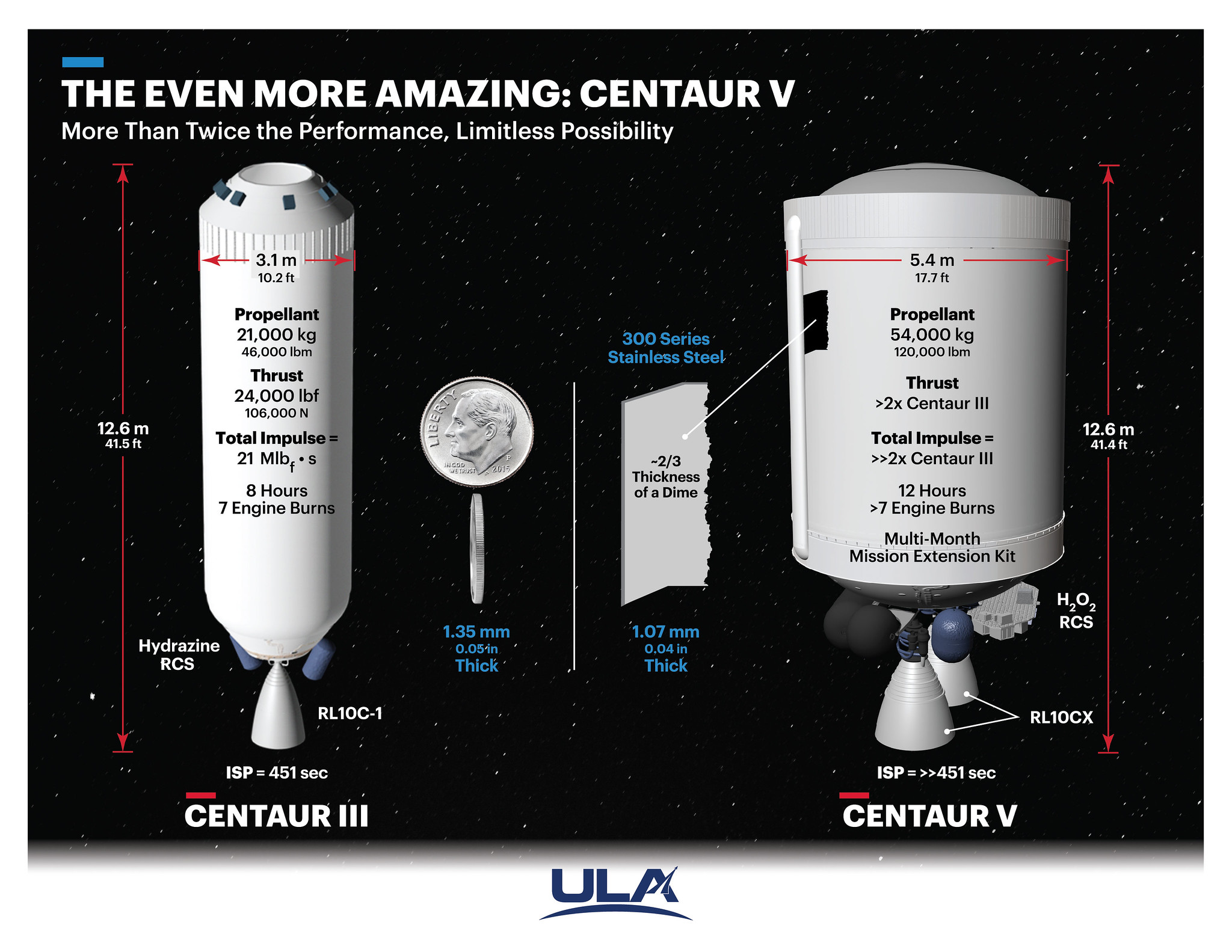

The Vulcan rocket is powered by two methane-fueled BE-4 engines produced by Jeff Bezos’ space company Blue Origin, and ULA can mount zero, two, four, or six strap-on solid rocket boosters from Northrop Grumman around the Vulcan’s first stage to propel heavier payloads to space. The rocket’s Centaur V upper stage is fitted with a pair of hydrogen-burning RL10 engines from Aerojet Rocketdyne.

The second Vulcan rocket will fly in the same configuration as the first launch earlier this year, with two strap-on solid-fueled boosters. The only noticeable modification to the rocket is the addition of some spray-on foam insulation around the outside of the first stage methane tank, which will keep the cryogenic fuel at the proper temperature as Vulcan encounters aerodynamic heating on its ascent through the atmosphere.

“This will give us just over one second more usable propellant,” Bruno wrote on X.

There is one more change from Vulcan’s first launch, which boosted a commercial lunar lander for Astrobotic on a trajectory toward the Moon. This time, there are no real spacecraft on the Vulcan rocket. Instead, ULA mounted a dummy payload to the Centaur V upper stage to simulate the mass of a functioning satellite.

ULA originally planned to launch Sierra Space’s first Dream Chaser spaceplane on the second Vulcan rocket. But the Dream Chaser won’t be ready to fly its first mission to resupply the International Space Station until next year. Under pressure from the Pentagon, ULA decided to move ahead with the second Vulcan launch without a payload at the company’s own expense, which Bruno tallied in the “high tens of millions of dollars.”

Heliocentricity

The test flight will begin with liftoff from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida, during a three-hour launch window opening at 6 am EDT (10: 00 UTC). The 202-foot-tall (61.6-meter) Vulcan rocket will head east over the Atlantic Ocean, shedding its boosters, first stage, and payload fairing in the first few minutes of flight.

The Centaur upper stage will fire its RL10 engines two times, completing the primary mission within about 35 minutes of launch. The rocket will then continue on for a series of technical demonstrations before ending up on an Earth escape trajectory into a heliocentric orbit around the Sun.

“We have a number of experiments that we’re conducting that are really technology demonstrations and measurements that are associated with our high-performance, longer-duration version of Centaur V that we’ll be introducing in the future,” Bruno said. “And these will help us go a little bit faster on that development. And, of course, because we don’t have an active spacecraft as a payload, we also have more instrumentation that we’re able to use for just characterizing the vehicle.”

The Centaur V upper stage for the Vulcan rocket. Credit: United Launch Alliance

ULA engineers have worked on the design of a long-lived upper stage for more than a decade. Their vision was to develop an upper stage fed by super-efficient cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants that could generate its own power and operate in space for days, weeks, or longer rather than an upper stage’s usual endurance limit of several hours. This would allow the rocket to not only deliver satellites into bespoke high-altitude orbits but also continue on to release more payloads at different altitudes or provide longer-term propulsion in support of other missions.

The concept was called the Advanced Cryogenic Evolved Stage (ACES). ULA’s corporate owners, Boeing and Lockheed Martin, never authorized the full development of ACES, and the company said in 2020 that it was no longer pursuing the ACES concept.

The Centaur V upper stage currently used on the Vulcan rocket is a larger version of the thin-walled, pressure-stabilized Centaur upper stage that has been flying since the 1960s. Bruno said the Centaur V design, as it is today, offers as much as 12 hours of operating life in space. This is longer than any other existing rocket using cryogenic propellants, which can boil off over time.

ULA’s chief executive still harbors an ambition for regaining some of the same capabilities promised by ACES.

“What we are looking to do is to extend that by orders of magnitude,” Bruno said. “And what that would allow us to do is have a in-space transportation capability for in-space mobility and servicing and things like that.”

Space Force leaders have voiced a desire for future spacecraft to freely maneuver between different orbits, a concept the military calls “dynamic space operations.” This would untether spacecraft operations from fuel limitations and eventually require the development of in-orbit refueling, propellant depots, or novel propulsion technologies.

No one has tried to store large amounts of super-cold propellants in space for weeks or longer. Accomplishing this is a non-trivial thermal problem, requiring insulation to keep heat from the Sun from reaching the liquid cryogenic propellant, stored at temperatures of several hundred degrees below zero.

Bruno hesitated to share details of the experiments ULA plans for the Centaur V upper stage on Friday’s test flight, citing proprietary concerns. He said the experiments will confirm analytical models about how the upper stage performs in space.

“Some of these are devices, some of these are maneuvers because maneuvers make a difference, and some are related to performance in a way,” he said. “In some cases, those maneuvers are helping us with the thermal load that tries to come in and boil off the propellants.”

Eventually, ULA would like to eliminate hydrazine attitude control fuel and battery power from the Centaur V upper stage, Bruno said Wednesday. This sounds a lot like what ULA wanted to do with ACES, which would have used an internal combustion engine called Integrated Vehicle Fluids (IVF) to recycle gasified waste propellants to pressurize its propellant tanks, generate electrical power, and feed thrusters for attitude control. This would mean the upper stage wouldn’t need to rely on hydrazine, helium, or batteries.

ULA hasn’t talked much about the IVF system in recent years, but Bruno said the company is still developing it. “It’s part of all of this, but that’s all I will say, or I’ll start revealing what all the gadgets are.”

A comparison between ULA’s legacy Centaur upper stage and the new Centaur V. Credit: United Launch Alliance

George Sowers, former vice president and chief scientist at ULA, was one of the company’s main advocates for extending the lifetime of upper stages and developing technologies for refueling and propellant depot. He retired from ULA in 2017 and is now a professor at the Colorado School of Mines and an independent aerospace industry consultant.

In an interview with Ars earlier this year, Sowers said ULA solved many of the problems with keeping cryogenic propellants at the right temperature in space.

“We had a lot of data on boil-off, just from flying Centaurs all the way to geosynchronous orbit, which doesn’t involve weeks, but it involves maybe half a day or so, which is plenty of time to get all the temperatures to stabilize at deep space levels,” Sowers said. “So you have to understand the heat transfer very well. Good models are very important.”

ULA experimented with different types of insulation and vapor cooling, which involves taking cold gas that boiled off of cryogenic fuel and blowing it on heat penetration points into the tanks.

“There are tricks to managing boil-off,” he said. “One of the tricks is that you never want to boil oxygen. You always want to boil hydrogen. So you size your propellant tanks and your propellant loads, assuming you’re going to have that extra hydrogen boil-off. Then what you can do is use the hydrogen to keep the oxygen cold to keep it from boiling.

“The amount of heat that you can reject by boiling off one kilogram of hydrogen is about five times what you would reject by boiling off one kilogram of oxygen. So those are some of the thermodynamic tricks,” Sowers said. “The way ULA accomplished that is by having a common bulkhead, so the hydrogen tank and the oxygen tank are in thermal contact. So hydrogen keeps the oxygen cold.”

ULA’s experiments showed it could get the hydrogen boil-off rate down to about 10 percent per year, based on thermodynamic models calibrated by data from flying older versions of the Centaur upper stage on Atlas V rockets, according to Sowers.

“In my mind, that kind of cemented the idea that distribution depots and things like that are very well in hand without having to have exotic cryocoolers, which tend to use a lot of power,” Sowers said. “It’s about efficiency. If you can do it passively, you don’t have to expend energy on cryocoolers.”

“We’re going to go to days, and then we’re going to go to weeks, and then we think it’s possible to take us to months,” Bruno said. “That’s a game changer.”

However, ULA’s corporate owners haven’t yet fully bought into this vision. Bruno said the Vulcan rocket and its supporting manufacturing and launch infrastructure cost between $5 billion and $7 billion to develop. ULA also plans to eventually recover and reuse BE-4 main engines from the Vulcan rocket, but that is still at least several years away.

But ULA is reportedly up for sale, and a well-capitalized buyer might find the company’s long-duration cryogenic upper stage more attractive and worth the investment.

“There’s a whole lot of missions that enables,” Bruno said. “So that’s a big step in capability, both for the United States and also commercially.”