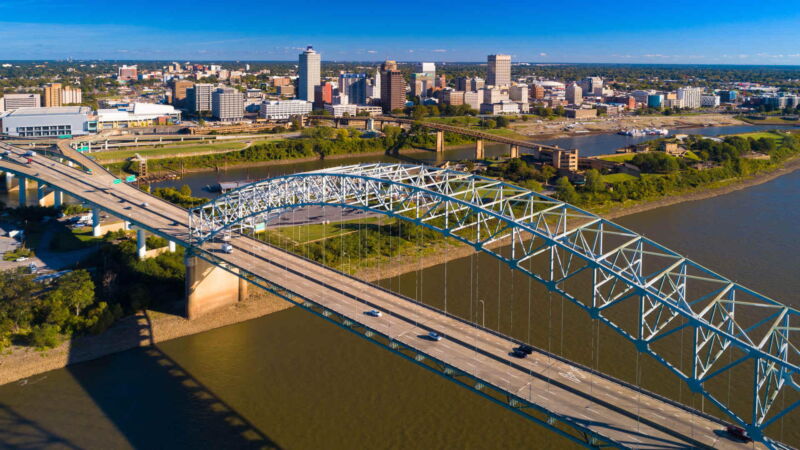

Enlarge / Top: A view of the downtown Memphis skyline, including the Hernando De Soto bridge which has been retrofitted for earthquakes. Memphis is located around 40 miles from a fault line in the quake-prone New Madrid system.

iStock via Getty Images

The first earthquake struck while the town was still asleep. Around 2: 00 am on Dec. 16, 1811, New Madrid—a small frontier settlement of 400 people on land now located in Missouri—was jolted awake. Panicked townsfolk fled their homes as buildings collapsed and the smell of sulfur filled the air.

The episode didn’t last long. But the worst was yet to come. Nearly two months later, after dozens of aftershocks and another massive quake, the fault line running directly under the town ruptured. Thirty-one-year-old resident Eliza Bryan watched in horror as the Mississippi River receded and swept away boats full of people. In nearby fields, geysers of sand erupted, and a rumble filled the air.

In the end, the town had dropped at least 15 feet. Bryan and others spent a year and a half living in makeshift camps while they waited for the aftershocks to end. Four years later, the shocks had become less common. At last, the rattled townspeople began “to hope that ere long they will entirely cease,” Bryan wrote in a letter.

Whether Bryan’s hope will stand the test of time is an open question.

The US Geological Survey released a report in December 2023 detailing the risk of dangerous earthquakes around the country. As expected on the hazard map, deep red risk lines run through California and Alaska. But the map also sports a big bull’s eye in the middle of the country—right over New Madrid.

The USGS estimates that the region has a 25 to 40 percent chance of a magnitude 6.0 or higher earthquake in the next 50 years, and as much as a 10 percent chance of a repeat of the 1811-1812 sequence. While the risk is much lower compared to, say, California, experts say that when it comes to earthquake resistance, the New Madrid region suffers from inadequate building codes and infrastructure.

Caught in this seismic splash zone are millions of people living across five states—mostly in Tennessee and Missouri, as well as Kentucky, Illinois, and Arkansas—including two major cities, Memphis and St. Louis. Mississippi, Alabama, and Indiana have also been noted as places of concern.

In response to the potential for calamity, geologists have learned a lot about this odd earthquake hotspot over the last few decades. Yet one mystery has persisted: why earthquakes even happen here in the first place.

This is a problem, experts say. Without a clear mechanism for why New Madrid experiences earthquakes, scientists are still struggling to answer some of the most basic questions, like when—or even if—another large earthquake will strike the region. In Missouri today, earthquakes are “not as front of mind” as other natural disasters, said Jeff Briggs, earthquake program manager for the Missouri State Emergency Management Agency.

But when the next big shake comes, “it’s going to be the biggest natural disaster this state has ever experienced.”