a rich hunting ground —

Researchers are working to limit the threat while developing better eradication methods.

Enlarge / 2023 marked the first sighting of a yellow-legged hornet in the United States, sparking fears that it may spread and devastate honeybees as it has in parts of Europe.

In early August 2023, a beekeeper near the port of Savannah, Georgia, noticed some odd activity around his hives. Something was hunting his honeybees. It was a flying insect bigger than a yellowjacket, mostly black with bright yellow legs. The creature would hover at the hive entrance, capture a honeybee in flight, and butcher it before darting off with the bee’s thorax, the meatiest bit.

“He’d only been keeping bees since March… but he knew enough to know that something wasn’t right with this thing,” says Lewis Bartlett, an evolutionary ecologist and honeybee expert at the University of Georgia, who helped to investigate. Bartlett had seen these honeybee hunters before, during his PhD studies in England a decade earlier. The dreaded yellow-legged hornet had arrived in North America.

With origins in Afghanistan, eastern China, and Indonesia, the yellow-legged hornet, Vespa velutina, has expanded during the last two decades into South Korea, Japan, and Europe. When the hornet invades new territory, it preys on honeybees, bumblebees, and other vulnerable insects. One yellow-legged hornet can kill up to dozens of honeybees in a single day. It can decimate colonies through intimidation by deterring honeybees from foraging. “They’re not to be messed with,” says honeybee researcher Gard Otis, professor emeritus at the University of Guelph in Canada.

The yellow-legged hornet is so destructive that it was the first insect to land on the European Union’s blacklist of invasive species. In Portugal, honey production in some regions of the country has slumped by more than 35 percent since the hornet’s arrival. French beekeepers have reported 30 percent to 80 percent of honeybee colonies exterminated in some locales, costing the French economy an estimated $33 million annually.

Enlarge / The yellow-legged hornet’s nests can be quite large and house as many as 6,000 workers.

All that destruction may be linked to a single, multi-mated queen that arrived at the port of Bordeaux, France, in a shipment of bonsai pots from China before 2004. During her first spring, she established a nest, reared workers, and laid eggs. By fall, hundreds of new mated queens likely exited and found overwintering sites, restarting the cycle in the spring. The hornet’s fortitude—it is the Diana Nyad of invasive social wasps—allowed it to surge across France’s borders into Spain, Portugal, Italy, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland in only two decades, hurtling onward by as much as 100 kilometers a year.

Suspected stowaway

As the hornet fanned out across Europe, scientists in North America wondered when it might arrive on their side of the Atlantic. Queens sometimes overwinter in crates and containers, allowing them to stow away on ships and be transported long distances. In 2013, researchers cautioned that a yellow-legged hornet invasion at any one point along the US East Coast would have the potential to spread across the country.

After the first sighting last summer, Georgia’s agricultural commissioner urged people to report hornets and nests, and warned that the yellow-legged hornet could threaten the state’s $73 billion agriculture industry. American farmers grow more than 100 different crops, including apples, blueberries, and watermelons, that depend on pollinators. Georgia mass-produces honeybees and ships them north to jumpstart spring crops, like Maine blueberries, before local pollinators have awakened.

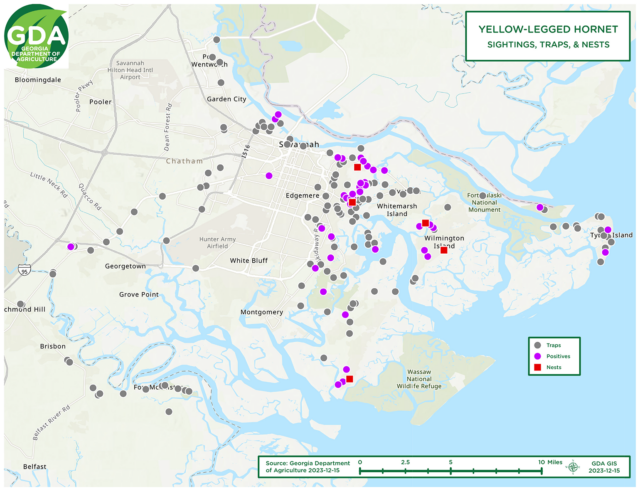

Enlarge / In response to the arrival of the yellow-legged hornet, the Georgia Department of Agriculture has placed hundreds of traps to monitor the insects’ spread near Savannah. This map shows the locations of those traps (gray dots), sightings of the hornet (pink dots) and five nests (red squares) as of December 15, 2023.

Less than two weeks after the first hornet was spotted, scientists found a nest in a tree 25 meters off the ground. In a night operation, while the hornets idled, a tree surgeon climbed to the nest, sprayed it with insecticide, and cut it down. Just a quarter of the full nest was the size of a human torso, and the Georgia Department of Agriculture displayed a chunk, still wrapped around the branch, at a press conference—warning that this was larger than those seen in Europe.

“Savannah, Georgia, is primo climate for these guys,” says Otis. It’s a lush, subtropical paradise, giving the insect a long growing season—and a rich hunting ground.

For the next several months, Bartlett helped the state agricultural researchers set traps and follow individual hornets to find other nests. By the end of 2023, they’d removed four more. “We think we’ve discovered them at a very early stage, which is why pursuing eradication is very, very plausible,” Bartlett said in November. If not, Georgia and its neighbors could get caught in an endless—and costly—game of whack-a-mole.