Arsenic and old books —

Old books with toxic dyes may be in universities, public libraries, private collections.

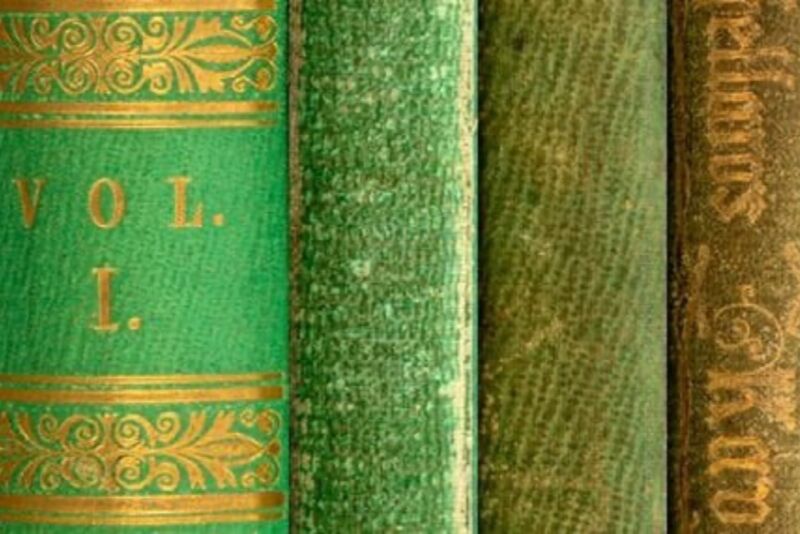

Enlarge / Composite image showing color variation of emerald green bookcloth on book spines, likely a result of air pollution

In April, the National Library of France removed four 19th century books, all published in Great Britain, from its shelves because the covers were likely laced with arsenic. The books have been placed in quarantine for further analysis to determine exactly how much arsenic is present. It’s part of an ongoing global effort to test cloth-bound books from the 19th and early 20th centuries because of the common practice of using toxic dyes during that period.

Chemists from Lipscomb University in Nashville, Tennessee, have also been studying Victorian books from that university’s library collection in order to identify and quantify levels of poisonous substances in the covers. They reported their initial findings this week at a meeting of the American Chemical Society in Denver. Using a combination of spectroscopic techniques, they found that several books had lead concentrations more than twice the limit imposed by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

The Lipscomb effort was inspired by the University of Delaware’s Poison Book Project, established in 2019 as an interdisciplinary crowdsourced collaboration between university scientists and the Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library. The initial objective was to analyze all the Victorian-era books in the Winterthur circulating and rare books collection for the presence of an arsenic compound called cooper acetoarsenite, an emerald green pigment that was very popular at the time to dye wallpaper, clothing, and cloth book covers. Book covers dyed with chrome yellow—favored by Vincent van Gogh— aka lead chromate, were also examined, and the project’s scope has since expanded worldwide.

The Poison Book Project is ongoing, but 50 percent of the 19th century cloth-case bindings tested so far contain lead in the cloth across a range of colors, as well as other highly toxic heavy metals: arsenic, chromium, and mercury. The French National Library’s affected books included the two-volume Ballads of Ireland by Edward Hayes (1855), an anthology of translated Romanian poetry (1856), and the Royal Horticultural Society’s book from 1862–1863.

Levels were especially high in those bindings that contain chrome yellow. However, the project researchers also determined that, for the moment at least, the chromium and lead in chrome yellow dyed book covers are still bound to the cloth. The emerald green pigment, on the other hand, is highly “friable,” meaning that the particles break apart under even small amounts of stress or friction, like rubbing or brushing up against the surface—and that pigment dust is hazardous to human health, particularly if inhaled.

Enlarge / Lipscomb University undergraduate Leila Ais cuts a sample from a book cover to test for toxic dyes.

Kristy Jones

The project lists several recommendations for the safe handling and storage of such books, such as wearing nitrile gloves—prolonged direct contact with arsenical green pigment, for instance, can lead to skin lesions and skin cancer—and not eating, drinking, biting one’s fingernails or touching one’s face during handling, as well as washing hands thoroughly and wiping down surfaces. Arsenical green books should be isolated for storage and removed from circulating collections, if possible. And professional conservators should work under a chemical fume hood to limit their exposure to arsenical pigment dust.

X-ray diffraction marks the spot

In 2022, Libscomb librarians heard about the Poison Book Project and approached the chemistry department about conducting a similar analytical survey of the 19th century books in the Beaman Library. “These old books with toxic dyes may be in universities, public libraries, and private collections,” said Abigail Hoermann, an undergraduate studying chemistry at Lipscomb University who is among those involved in the effort, led by chemistry professor Joseph Weinstein-Webb. “So, we want to find a way to make it easy for everyone to be able to find what their exposure is to these books, and how to safely store them.”

The team relied upon X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to conduct a broad survey of the collection to determine the presence of arsenic or other heavy metals in the covers, followed by plasma optical emission spectroscopy to measure the concentrations in snipped samples from book covers where such poisons were found. They also took their analysis one step further by using X-ray diffraction to identify the specific pigment molecules within the detected toxic metals.

The results so far: Lead and chromium were present in several books in the Lipscomb collection, with high levels of lead and chromium in some of those samples. The highest lead level measured was more than twice the CDC limit, while the highest chromium concentration was six times the limit.

The Lipscomb library decided to seal any colored 19th century books not yet tested in plastic for storage pending analysis. Those books, now known to have covers colored with dangerous dyes, have been removed from public circulation and also sealed in plastic bags, per Poison Book Project recommendations.

The XRD testing showed that lead(II) chromate was present in a few of those heavy metals as well—a compound of the chrome yellow pigment. In fact, they were surprised to find that the book covers contained far more lead than chromium, given that there are equal amounts of both in lead(II) chromate. Further research is needed, but the working hypothesis is that there may be other lead-based pigments—lead(II) oxide, perhaps, or lead(II) sulfide—in the dyes used on those covers.