Brace for impact —

Seismic information now allows us to make a planet-wide estimate of impact rates.

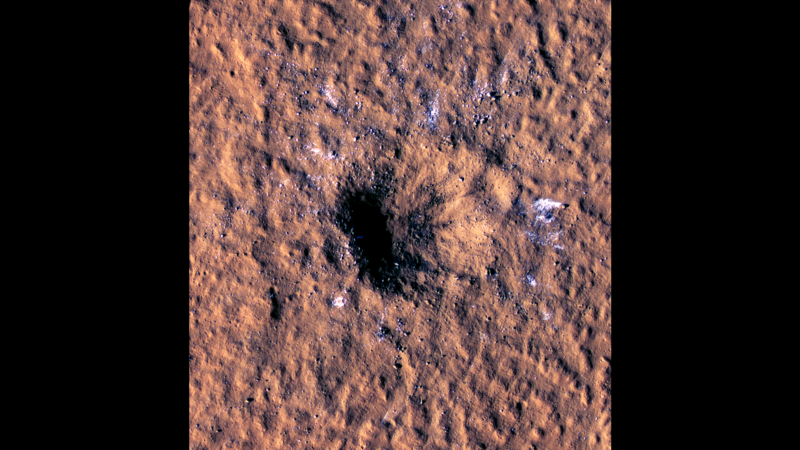

Enlarge / One of the craters identified seismically, then confirmed through orbital images.

Mars trembles with marsquakes, but not all of them are driven by phenomena that occur beneath the surface—many are the aftermath of meteorite strikes.

Meteorites crash down to Mars every day. After analyzing data from NASA’s InSight lander, an international team of researchers noticed that its seismometer, SEIS, detected six nearby seismic events. These were linked to the same acoustic atmospheric signal that meteorites generate when whizzing through the atmosphere of Mars. Further investigation identified all six as part of an entirely new class of quakes known as VF (very high frequency) events.

The collisions that generate VF marsquakes occur in fractions of a second, much less time than the few seconds it takes tectonic processes to cause quakes similar in size. This is some of the key seismological data that has helped us understand the occurrence of earthquakes caused by meteoric impacts on Mars. This is also the first time seismic data was used to determine how frequently impact craters are formed.

“Although a non-impact origin cannot be definitively excluded for each VF event, we show that the VF class as a whole is plausibly caused by meteorite impacts,” the researchers said in a study recently published in Nature.

Seismic shift

Scientists had typically determined the approximate meteorite impact rate on Mars by comparing the frequency of craters on its surface to the expected rate of impacts calculated using counts of lunar craters that were left behind by meteorites. Models of the lunar cratering rate were then adjusted to fit Martian conditions.

Looking to the Moon as a basis for comparison was not ideal, as Mars is especially prone to being hit by meteorites. The red planet is not only a more massive body that has greater gravitational pull, but it is located near the asteroid belt.

Another issue is that lunar craters are often better preserved than Martian craters because there is no place in the Solar System dustier than Mars. Craters in orbital images are often partly obscured by dust, which makes them difficult to identify. Sandstorms can complicate matters by covering craters in more dust and debris (something that cannot occur on the Moon due to the absence of wind).

InSight deployed its SEIS instrument after it landed in the Elysium Planitia region of Mars. In addition to detecting tectonic activity, the seismometer can potentially determine the impact rate through seismic data. When meteorites strike Mars, they produce seismic waves just like tectonic marsquakes do, and the waves can be detected by seismometers when they travel through the mantle and crust. An immense quake picked up by SEIS was linked to a crater 150 meters (492 feet) wide. SEIS would later detect five more marsquakes that were all associated with an acoustic signal (detected by a different sensor on InSight) that is a telltale sign of a falling meteorite.

A huge impact

Something else stood out about the six impact-driven marsquakes detected with seismic data. Because of the velocity of meteorites (over 3,000 meters or 9,842 feet per second), these events happened faster than any other type of marsquake, even faster than quakes in the high frequency (HF) class. That’s how they earned their own classification: very high frequency, or VF, quakes. When the InSight team used the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s (MRO) Context Camera (CTX) to image the locations of the events picked up by SEIS, there were new craters present in the images.

There are additional seismic events that haven’t been assigned to craters yet. They are thought to be small craters formed by meteorites about the size of basketballs, which are extremely difficult to see in orbital images from MRO.

The researchers were able to use SEIS data to estimate the diameters of craters based on distance from InSight (according to how long it took seismic waves to reach the spacecraft) and the magnitude of the VF marsquakes associated with them. They were also able to derive the frequency of quakes picked up by SEIS. Once a frequency estimate based on the data was applied to the entire surface area of Mars, they estimated that around 280 to 360 VF quakes occur each year.

“The case is strong that the unique VF marsquake class is consistent with impacts,” they said in the same study. “It is, therefore, worthwhile considering the implications of attributing all VF events to meteoroid impacts.”

Their detection has added to the estimated number of impact craters on Mars since many could not be seen from space before. What can VF impacts tell us? The impact rate on a planet or moon is important for determining the age of that object’s surface. Using impacts has helped us determine that the surface of Venus is constantly being renewed by volcanic activity, while most of the surface of Mars has not been covered in lava for billions of years.

Figuring out the rate of meteorite impacts can also help protect spacecraft and, someday, maybe Martian astronauts, from potential hazards. The study suggests that there are periods where impacts are more or less frequent, so it might be possible to predict when the sky is a bit more likely to be clear of falling space rocks—and when it isn’t. Meteorites are not much of a danger to Earth since most of them burn up in the atmosphere. Mars has a much thinner atmosphere that more can make it through, and there is no umbrella for a meteor shower.

Nature Astronomy, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02301-z