You know that new sound you’re looking for? —

Cornell staff finish the job with new technology but keep Moog’s work in place.

Ryan Young/Cornell University

Mathematician and early AI theorist David Rothenberg was fascinated by pattern-recognition algorithms. By 1968, he’d already done lots of work in missile trajectories (as one did back then), speech, and accounting, but he had another esoteric area he wanted to explore: the harmonic scale, as heard by humans. With enough circuits and keys, you could carve up the traditional music octave from 12 tones into 31 and make all kinds of between-tone tunes.

Happily, he had money from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, and he also knew just the person to build this theoretical keyboard: Robert Moog, a recent graduate from Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, who was just starting to work toward a fully realized Moog Music.

The plans called for a 478-key keyboard, an analog synthesizer, a bank of oscillators, and an impossibly intricate series of circuits between them. Moog “took his time on this,” according to Travis Johns, instructional technologist at Cornell. He eventually delivers a one-octave prototype made from “1960s-era, World-War-II-surplus technology.” Rothenberg held onto the keyboard piece, hoping to one day finish it, until his death in 2018. His widow, Suhasini Sankaran, donated the kit to Cornell in 2022.

Because of that noble garage-cleaning, there now exists a finished device, one that has had work composed and performed upon it: the Moog-Rothenberg Keyboard.

Cornell’s telling of the Moog-Rothenberg keyboard, restored by university staff and students.

The project didn’t start until February 2023, partly because of the intimidating nature of working on a one-of-a-kind early synth prototype. “I would hate to unsolder something that was soldered 50 years ago by Robert Moog,” Johns says in the video.

Johns and his students and staff at Cornell sought to honor the original intent and schematics of the device but not ignore the benefits of modern tech. Programmable micro-controllers were used to divide up an 8 MHz clock signal, creating circuits with several octaves of the same note. Those controllers were then wired, laboriously, to the appropriate keys.

-

Original designs for the Moog-Rothenberg keyboard.

Ryan Young/Cornell University

-

Travis Johns works on some of the newer pieces of the restored (or replicated) Moog-Rothenberg keyboard.

Ryan Young/Cornell University

-

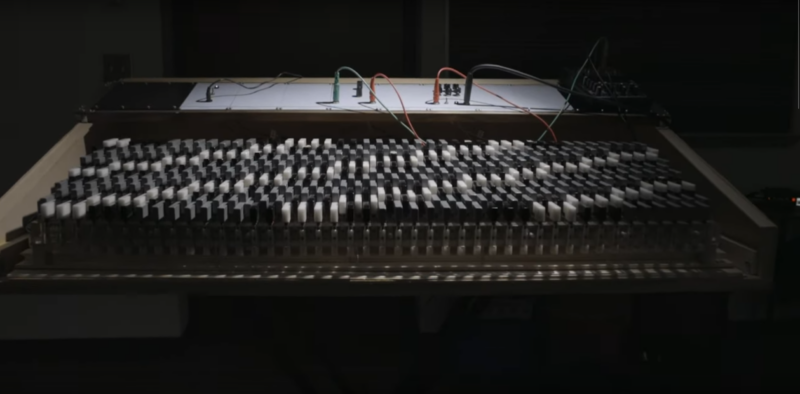

Switches and microcontrollers for the fully realized keyboard.

Ryan Young/Cornell University

-

A bit closer up with some of the original wiring for the one-octave prototype Moog prepared in the late 1960s.

Ryan Young/Cornell University

-

Even closer to those circuits and keypads.

Ryan Young/Cornell University

As Johns notes, it’s hard to categorize the synthesizer now as the original object, a re-creation, or a “playable facsimile” of a planned device. It’s also a particularly strange instrument. His team followed every mathematical and electrical detail of the original plans but found that the keyboard took on “a life of its own,” creating unusual timbres, resonances, and even volumes as soundwaves synchronized and fell away. This is, of course, the kind of thing Rothenberg originally hired Moog to make possible.

By October, the 31-tone synth was ready to play some music. Cornell professors Xak Bjerken and Elizabeth Ogonek performed and composed for it, respectively, and they were joined by members of Cornell’s EZRA quartet, themselves no stranger to strange instruments and new styles. Bjerken described his set as “bluegrass meets experimental improvisation.”

You can certainly hear the experimental come through in bits of the performance captured by Cornell. Ogonek manually controlled the instrument’s filters during the concert to create sustained tones. It requires more than two hands to control the output of 478 keys. The synthesizer now resides in Cornell’s Lincoln Hall for the Department of Music.