Invention of printing press, influence of nearby cities created perfect conditions for social contagion.

Between 1400 and 1775, a significant upsurge of witch trials swept across early-modern Europe, resulting in the execution of an estimated 40,000–60,000 accused witches. Historians and social scientists have long studied this period in hopes of learning more about how large-scale social changes occur. Some have pointed to the invention of the printing press and the publication of witch-hunting manuals—most notably the highly influential Malleus maleficarum—as a major factor, making it easier for the witch-hunting hysteria to spread across the continent.

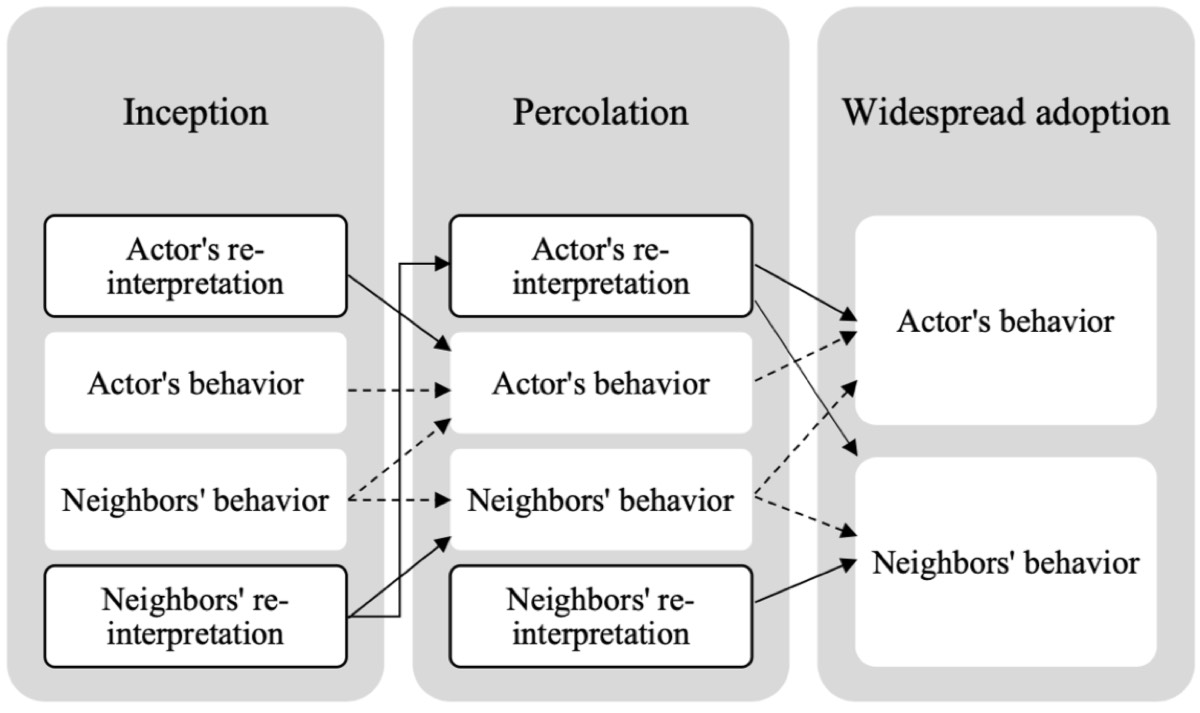

The abrupt emergence of the craze and its rapid spread, resulting in a pronounced shift in social behaviors—namely, the often brutal persecution of suspected witches—is consistent with a theory of social change dubbed “ideational diffusion,” according to a new paper published in the journal Theory and Society. There is the introduction of new ideas, reinforced by social networks, that eventually take root and lead to widespread behavioral changes in a society.

The authors had already been thinking about cultural change and the driving forces by which it occurs, including social contagion—especially large cultural shifts like the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, for example. One co-author, Steve Pfaff, a sociologist at Chapman University, was working on a project about witch trials in Scotland and was particularly interested in the role the Malleus maleficarum might have played.

“Plenty of other people have written about witch trials, specific trials or places or histories,” co-author Kerice Doten-Snitker, a social scientist with the Santa Fe Institute, told Ars. “We’re interested in building a general theory about change and wanted to use that as a particular opportunity. We realized that the printing of the Mallleus maleficarum was something we could measure, which is useful when you want to do empirical work, not just theoretical work.”

Ch-ch-ch-changes…

The Witch, No. 1, c. 1892 lithograph by Joseph E. Baker. Credit: Public domain

Modeling how sweeping cultural change happens has been a hot research topic for decades, hitting the cultural mainstream with the publication of Malcolm Gladwell’s 2000 bestseller The Tipping Point. Researchers continue to make advances in this area. University of Pennsylvania sociologist Damon Centola, for instance, published How Behavior Spreads: the Science of Complex Contagions in 2018, in which he applied new lessons learned in epidemiology—on how viral epidemics spread—to our understanding of how social networks can broadly alter human behavior. But while epidemiological modeling might be useful for certain simple forms of social contagion—people come into contact with something and it spreads rapidly, like a viral meme or hit song—other forms of social contagion are more complicated, per Doten-Snitker.

Doten-Snitker et al.’s ideational diffusion model differs from Centola’s in some critical respects. For cases like the spread of witch trials, “It’s not just that people are coming into contact with a new idea, but that there has to be something cognitively that is happening,” said Doten-Snitker. “People have to grapple with the ideas and undergo some kind of idea adoption. We talk about this as reinterpreting the social world. They have to rethink what’s happening around them in ways that make them think that not only are these attractive new ideas, but also those new ideas prescribe different types of behavior. You have to act differently because of what you’re encountering.”

The authors chose to focus on social networks and trade routes for their analysis of the witch trials, building on prior research that prioritized broader economic and environmental factors. Cultural elites were already exchanging ideas through letters, but published books added a new dimension to those exchanges. Researchers studying 21st century social contagion can download massive amounts of online data from social networks. That kind of data is sparse from the medieval era. “We don’t have the same archives of communication,” said Doten-Snitker. “There’s this dual thing happening: the book itself, and people sharing information, arguing back and forth with each other” about new ideas.

The stages of the ideation diffusion model. Credit: K. Dooten-Snitker et al., 2024

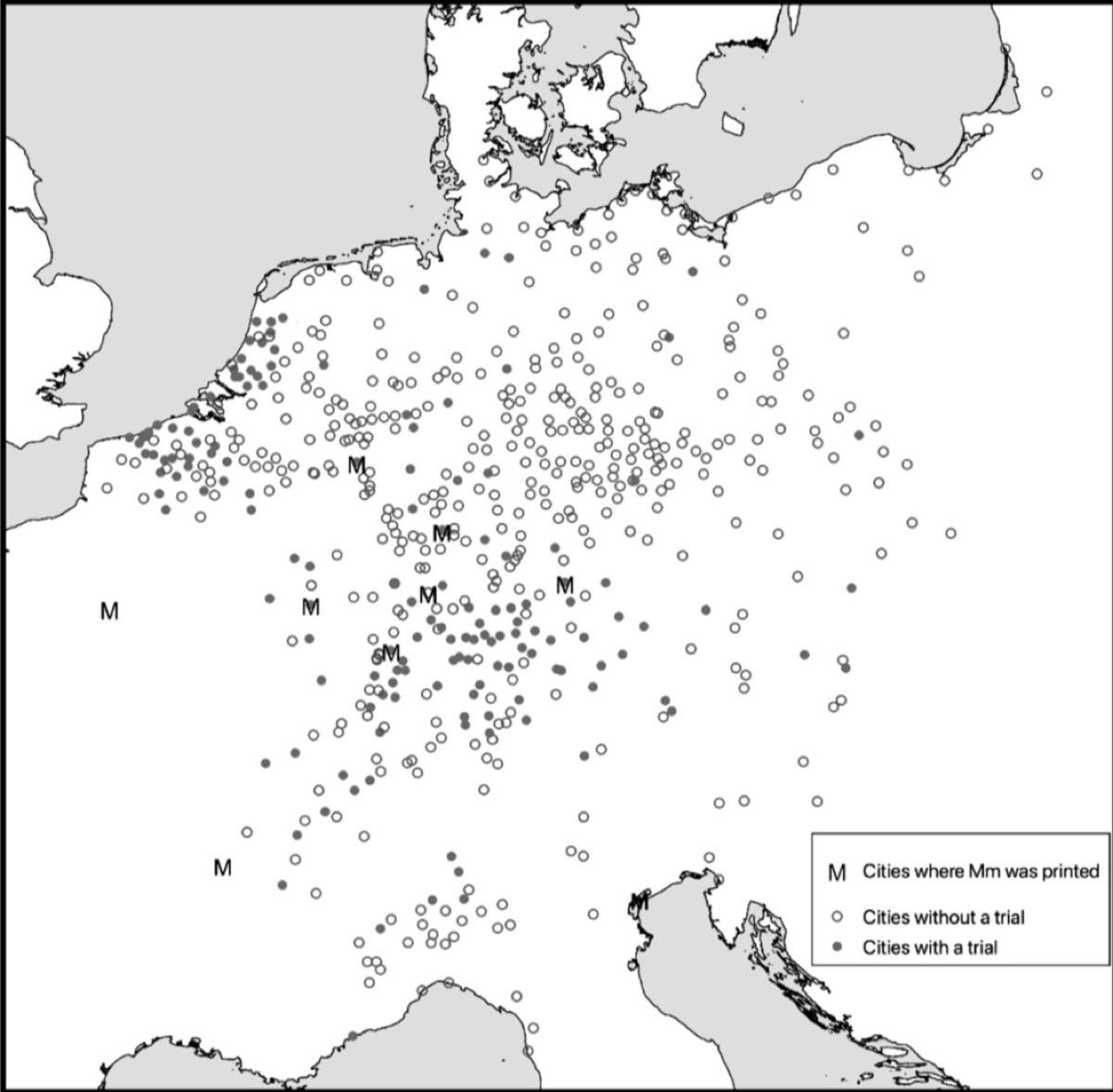

So she and her co-authors et al. turned to trade routes to determine which cities were more central and thus more likely to be focal points of new ideas and information. “The places that are more central in these trade networks have more stuff passing through and are more likely to come into contact with new ideas from multiple directions—specifically ideas about witchcraft,” said Doten-Snitker. Then they looked at which of 553 cities in Central Europe held their first witch trials, and when, as well as those where the Malleus maleficarum and similar manuals had been published.

Social contagion

They found that each new published edition of the Malleus maleficarum corresponded with a subsequent increase in witch trials. But that wasn’t the only contributing factor; trends in neighboring cities also influenced the increase, resulting in a slow-moving ripple effect that spread across the continent. “What’s the behavior of neighboring cities?” said Doten-Snitker. “Are they having witch trials? That makes your city more likely to have a witch trial when you have the opportunity.”

In epidemiological models like Centola’s, the pattern of change is a slow start with early adoption that then picks up speed and spreads before slowing down again as a saturation point is reached, because most people have now adopted the new idea or technology. That doesn’t happen with witch trials or other complex social processes such as the spread of medieval antisemitism. “Most things don’t actually spread that widely; they don’t reach complete saturation,” said Doten-Snitker. “So we need to have theories that build that in as well.”

In the case of witch trials, the publication of the Malleus maleficarum helped shift medieval attitudes toward witchcraft, from something that wasn’t viewed as a particularly pressing problem to something evil that was menacing society. The tome also offered practical advice on what should be done about it. “So there’s changing ideas about witchcraft and this gets coupled with, well, you need to do something about it,” said Doten-Snitker. “Not only is witchcraft bad, but it’s a threat. So you have a responsibility as a community to do something about witches.”

The term “witch hunt” gets bandied about frequently in modern times, particularly on social media, and is generally understood to reference a mob mentality unleashed on a given target. But Doten-Snitker emphasizes that medieval witch trials were not “mob justice”; they were organized affairs, with official accusations to an organized local judiciary that collected and evaluated evidence, using the Malleus malficarum and similar treatises as a guide. The process, she said, is similar to how today’s governments adopt new policies.

Why conspiracy theories take hold

Cities where witch trials did and did not take place in Central Europe, 1400–1679, as well as those with printed copies of the Malleus Maleficarum. Credit: K. Doten-Snitker et al., 2024

The authors developed their model using the witch trials as a useful framework, but there are contemporary implications, particularly with regard to the rampant spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories via social media. These can also lead to changes in real-world behavior, including violent outbreaks like the January 6, 2021, attack on the US Capitol or, more recently, threats aimed at FEMA workers in the wake of Hurricane Helene. Doten-Snitker thinks their model could help identify the emergence of certain telltale patterns, notably the combination of the spread of misinformation or conspiracy theories on social media along with practical guidelines for responding.

“People have talked about the ways that certain conspiracy theories end up making sense to people,” said Doten-Snitker. “It’s because they’re constructing new ways of thinking about their world. This is why people start with one conspiracy theory belief that is then correlated with belief in others. It’s because you’ve already started rebuilding your image of what’s happening in the world around you and that serves as a basis for how you should act.”

On the plus side, “It’s actually hard for something that feels compelling to certain people to spread throughout the whole population,” she said. “We should still be concerned about ideas that spread that could be socially harmful. We just need to figure out where it might be most likely to happen and focus our efforts in those places rather than assuming it is a global threat.”

There was a noticeable sharp decline in both the frequency and intensity of witch trial persecutions in 1679 and onward, raising the question of how such cultural shifts eventually ran their course. That aspect is not directly addressed by their model, according to Doten-Snitker, but it does provide a framework for the kinds of things that might signal a similar major shift, such as people starting to push back against extreme responses or practices. In the case of the tail end of the witch trials craze, for instance, there was increased pressure to prioritize clear and consistent judicial practices that excluded extreme measures such as extracting confessions via torture, for example, or excluding dreams as evidence of witchcraft.

“That then supplants older ideas about what is appropriate and how you should behave in the world and you could have a de-escalation of some of the more extremist tendencies,” said Doten-Snitker. “It’s not enough to simply say those ideas or practices are wrong. You have to actually replace it with something. And that is something that is in our model. You have to get people to re-interpret what’s happening around them and what they should do in response. If you do that, then you are undermining a worldview rather than just criticizing it.”

Theory and Society, 2024. DOI: 10.1007/s11186-024-09576-1 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior reporter at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.