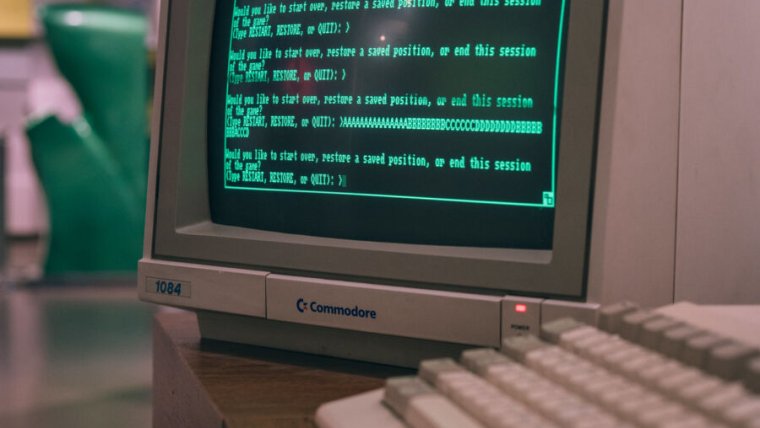

Enlarge / Zork running on an Amiga at the Computerspielemuseum in Berlin, Germany.

You are standing at the end of a road before a small brick building.

That simple sentence first appeared on a PDP-10 mainframe in the 1970s, and the words marked the beginning of what we now know as interactive fiction.

From the bare-bones text adventures of the 1980s to the heartfelt hypertext works of Twine creators, interactive fiction is an art form that continues to inspire a loyal audience. The community for interactive fiction, or IF, attracts readers and players alongside developers and creators. It champions an open source ethos and a punk-like individuality.

But whatever its production value or artistic merit, at heart, interactive fiction is simply words on a screen. In this time of AAA video games, prestige television, and contemporary novels and poetry, how does interactive fiction continue to endure?

To understand the history of IF, the best place to turn for insight is the authors themselves. Not just the authors of notable text games—although many of the people I interviewed for this article do have that claim to fame—but the authors of the communities and the tools that have kept the torch burning. Here’s what they had to say about IF and its legacy.

Examine roots: Adventure and Infocom

The interactive fiction story began in the 1970s. The first widely played game in the genre was Colossal Cave Adventure, also known simply as Adventure. The text game was made by Will Crowther in 1976, based on his experiences spelunking in Kentucky’s aptly named Mammoth Cave. Descriptions of the different spaces would appear on the terminal, then players would type in two-word commands—a verb followed by a noun—to solve puzzles and navigate the sprawling in-game caverns.

During the 1970s, getting the chance to interact with a computer was a rare and special thing for most people.

“My father’s office had an open house in about 1978,” IF author and tool creator Andrew Plotkin recalled. “We all went in and looked at the computers—computers were very exciting in 1978—and he fired up Adventure on one of the terminals. And I, being eight years old, realized this was the best thing in the universe and immediately wanted to do that forever.”

“It is hard to overstate how potent the effect of this game was,” said Graham Nelson, creator of the Inform language and author of the landmark IF Curses, of his introduction to the field. “Partly that was because the behemoth-like machine controlling the story was itself beyond ordinary human experience.”

Perhaps that extraordinary factor is what sparked the curiosity of people like Plotkin and Nelson to play Adventure and the other text games that followed. The roots of interactive fiction are entangled with the roots of the computing industry. “I think it’s always been a focus on the written word as an engine for what we consider a game,” said software developer and tech entrepreneur Liza Daly. “Originally, that was born out of necessity of primitive computers of the ’70s and ’80s, but people discovered that there was a lot to mine there.”

Home computers were just beginning to gain traction as Stanford University student Don Woods released his own version of Adventure in 1977, based on Crowther’s original Fortran work. Without wider access to comparatively pint-sized machines like the Apple 2 and the Vic-20, Scott Adams might not have found an audience for his own text adventure games, released under his company Adventure International, in another homage to Crowther. As computers spread to more people around the world, interactive fiction was able to reach more and more readers.