I call the section ‘Money Stuff’ but as a column name that is rather taken. There has been lots to write about on this front that didn’t fall neatly into other categories. It clearly benefited a lot from being better organized into subsections, and the monthly roundups could benefit from being shorter, so this will probably become a regular thing.

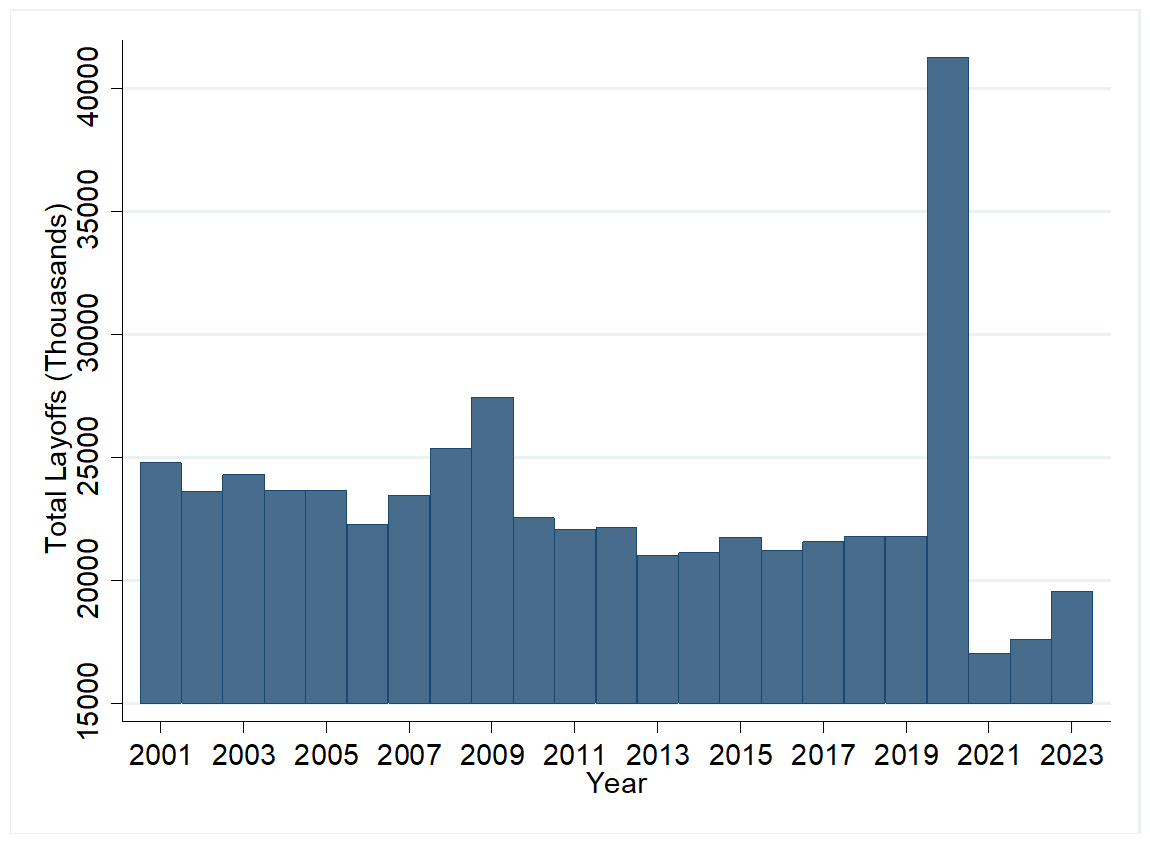

Quite the opposite, actually. Jobs situation remains excellent.

Whatever else you think of the economy, layoffs are still at very low levels, the last three years are the lowest levels on record, do note that the bottom of this chart is 15,000 rather than zero even without adjusting for population size.

Ford says it is reexamining where to make cars after the UAW strikes. The union responded by saying, essentially, ‘fyou, pay me’:

“Maybe Ford doesn’t need to move factories to find the cheapest labor on Earth,” he said. “Maybe it needs to recommit to American workers and find a CEO who’s interested in the future of this country’s auto industry,” Fain said.

Which is, of course, what both of them would always say no matter what. I do presume that now that the UAW has raised the price and expected future price of dealing with them, Ford is now placing a higher priority in getting new factories and jobs outside the reach of the UAW.

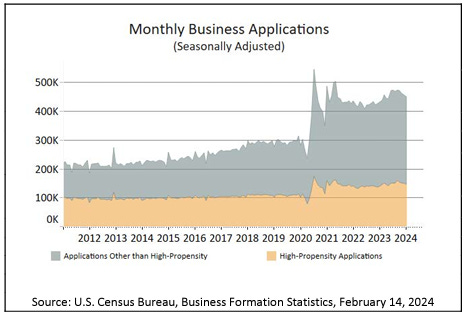

Something rather remarkable happened here in 2020.

High-propensity applications means businesses likely to hire employees with payroll. The number was holding steady for a decade at 100k such applications per month, then it jumped and is now stable at closer to 150k, with other applications a similar percentage above previous trend. This really is a big game.

Tom Gara: NY Mag’s personal finance columnist was convinced by a cold caller claiming to be a CIA agent in Langley that she needed to empty her bank account, put the money in a shoebox and give it to a guy coming to meet her on the street.

Falling for this scam was unbelievably stupid. I do not understand how they pulled this off and she fell for it. However writing the details of this up is a public service, as is admitting that this happened to you, so we thank her for that.

Critical Bureaucracy Theory: A lot of people dunking on this, but she’s doing society a service by describing it in detail, at her own expense.

Knowing about index funds and being able to compound performance doesn’t necessarily make you immune to pressure tactics.

Andrew Rettek: I would not hand $50,000 to a stranger.

I mean yes, that is true, it is possible to be good at figuring out index funds while still falling for scams. Indeed, a key reason to invest in index funds is that you do not have good judgment, the whole idea is that index funds do not use judgment. I still do think that there is a common factor that I want present wherever I seek advice.

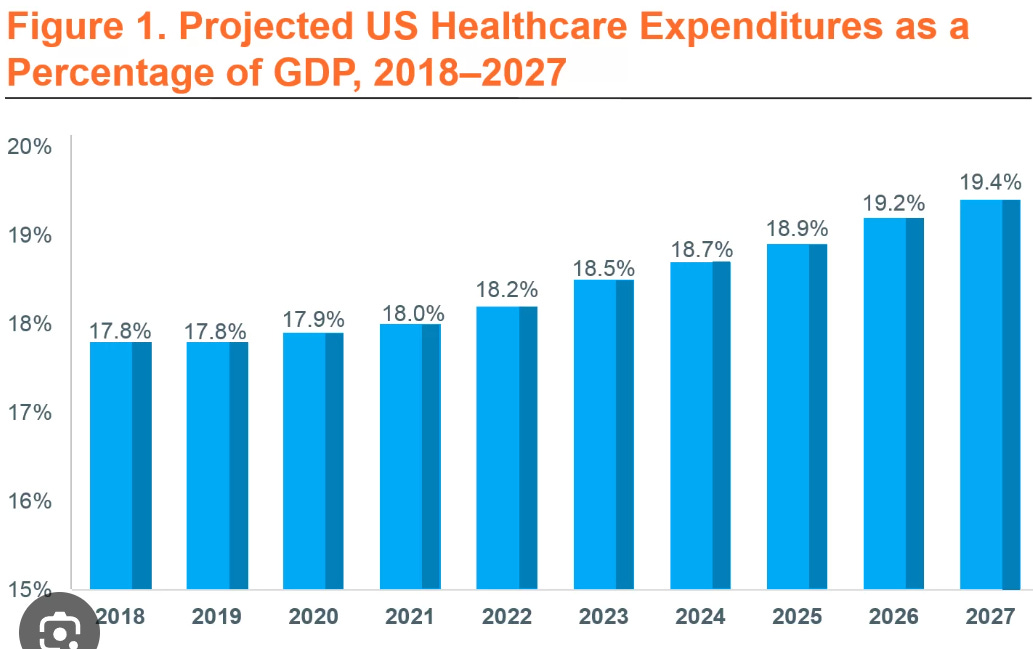

Arnold Kling links to Moses Strenstein, with the claim that GDP growth is ‘driven primarily by old folks buying healthcare stuff (variously, on the taxpayer’s dime.)

As always, one can check the data. Even if you think GDP is not a good measure, the healthcare share of GDP should check out.

Health care spending continues to rise as a share of GDP, but it is clearly not growing so fast that we lack other RGDP gains.

It does seem valid to say that marginal healthcare spending is Hansonian, as in spending more does not lead to better health or less death, so any such increases in spending should be considered wasted, and not count as people being better off.

(As usual, standard caveat that of course much of healthcare is highly valuable, as was driven home to me this past two weeks. I am fine now.)

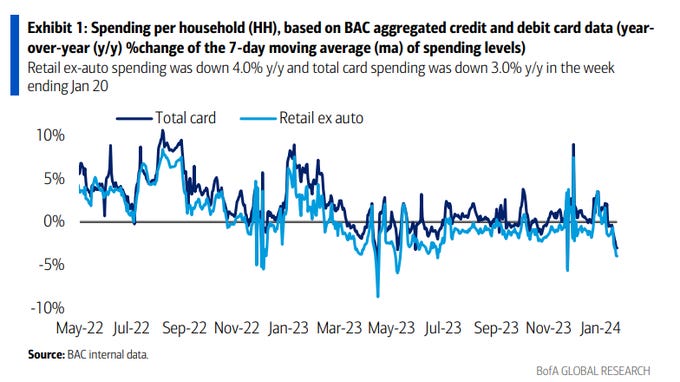

Similarly, Moses claims service inflation is still too high, but we should expect service inflation to exceed general inflation, and indeed want that to drive up real wages. And he complains that consumer spending is down:

Is higher consumer spending the goal, a cause, or both? I get confused about that. If people think the economy is bad so they cut their spending, that can make things bad, but if they do that and the economy remains good then that seems great and should lead to more savings and investment? Whereas the savings rate is quite low? So what is going on, if both savings and consumer spending are down, but GDP is up? That part does seem suspicious on first glance. It can be explained, and some of the explanations pass muster, but it is not going to feel like a good economy even then.

Yet another round of ‘life can’t be bad look at all your Nice Things.’

Overeducated Gibbon: All these doomposts about how people are worse off materially than they used to be, but then I look at the size of houses people buy, the niceness of cars they drive, the massive increase in air travel, the boom in restaurant spending etc.

Marc Andreessen: 💯

I continue to think that we can simultaneously live in what in many ways is great material abundance, and also be materially worse off. Yes, the basket of goods we currently buy was impossible to access in the past and would have been immensely costly. Yes, we have much better material possessions in many, even most, ways.

None of that matters if mandatory largely signaling and positional goods, especially education, health care and housing, are eating everyone’s budgets alive, to the point where many people feel they cannot afford children, and few feel they can afford four or more children. No cell phone or fast car is going to make up for that.

Our houses and apartments are bigger, but a lot of that is that they are required to be bigger, from a mix of regulations and cultural expectations. Being forced to buy more housing than you need, that you cannot afford, is not doing you any favors.

Vibecession Even if Inaccurate

As Scott Sumner points out, we are also clearly outperforming all our rivals. He ascribes this misconception to bad luck. I agree it is bad luck, but in terms of the initial conditions handed to Biden.

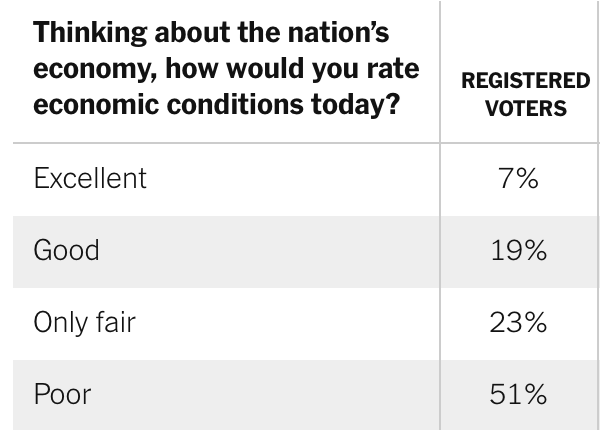

Scott Sumner also makes the case that yes, the economy is actually good, the numbers are real, it is that the public is being dumb at evaluating conditions, it is bad at that, you can tell because all they actually know are local conditions and they agree local conditions are fine.

I do think people are making the mistake of not comparing conditions to the right counterfactuals, not considering the initial conditions of the pandemic and previous administration’s choices, and not having reasonable expectations going forward. Compared to what could have been reasonably expected, compared to how others are doing, we are doing well.

Given those conditions, Biden needed to manage expectations, to explain the consequences of our Covid economic policies. Instead, he did not explain any of that, and then spent more.

Also people do not remember what the past was like, and imagine people used to be much richer than they were, with better consumption of goods then they had, and less stupid annoyances and time sinks than there were.

Most basically they forget how much more money people now make.

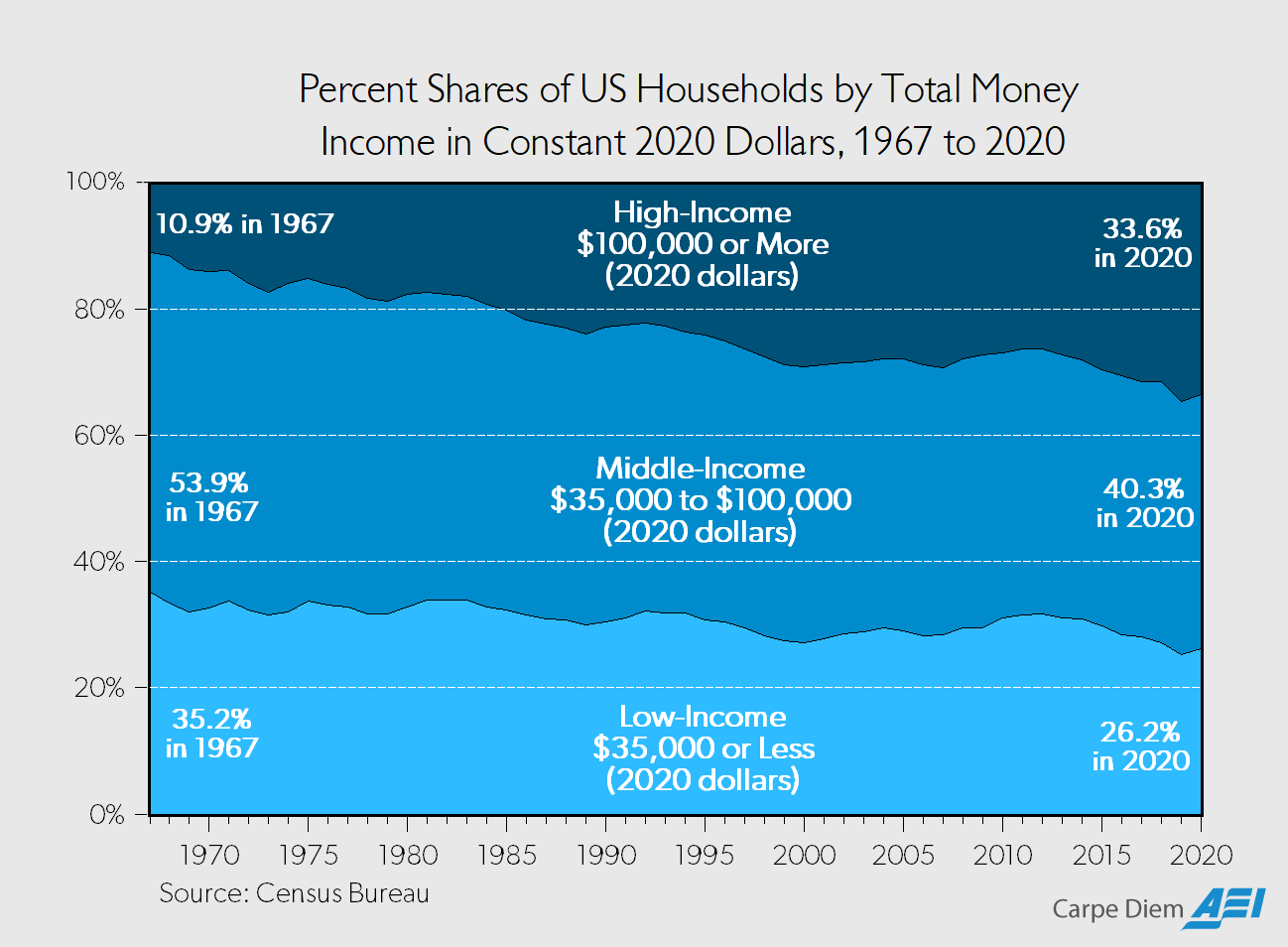

As some commenters point out, to the extent people are moving up in the general, that does not move up people overall in relative terms. So if your sense of ‘middle class’ membership, and what it means for middle class people to do well, is mostly relative, then this chart is a problem for those not in that new upper third.

Scott Sumner asks a related question more generally. Should a price index measure constant utility or constant quantity, or what?

Imagine an economy where the aggregate quantity of the only good increases at 5% per year, while the price of that good rises by 10%/year. You can think of that economy as having a 15% nominal growth rate. (I’ll ignore compounding for simplicity; technically it’s 15.5%). How much extra income would a person need each year in order to maintain a constant utility? I’m not sure, but I’m pretty confident the answer is not 10%, and it’s also not 15%.

1. A person that got a 15% raise would be able to buy 5% more real goods. So presumably their utility would be higher than before.

2. A person that got a 10% raise would be able to buy the same amount of goods, while that person’s acquaintances would be 5% ahead in real terms. So presumably that person would feel worse off in terms of utility.

This suggests that a measure of inflation that holds utility constant would be somewhere between 10% and 15%.

One index has to create one number. Then that number is equated to multiple different things.

It gets even more complicated if the quality of those goods also rises 10%/year, for varying versions of quality.

Let’s assume that instead of holding utility constant, we hold quantity constant. Then it becomes easy to calculate inflation—which would be exactly 10% in this case. Unfortunately, our textbooks seem to conflate “constant quantity” and “constant utility” in a way that ignores the social aspect of consumption.

My thought experiment involves an economy where quantity grows over time. But the same problem occurs with quality improvements. Here again, a “hedonic” adjustment that attempts to account for quality changes will typically come up with a lower estimate of inflation than an index that holds utility constant. Thus the BLS says that the price of TVs has fallen by more than 99% since 1959 (due to quality improvements), but average people don’t think that way.

They want to know how much more it costs to buy the sort of TV their neighbors have, not how much more it costs to buy the sort of TV their grandparents had.

You want to know all of these things.

You definitely want to know what it costs to get the things people typically get, so you can feel like you are keeping up, maintaining social status and dignity, buying what you are entitled to. The Iron Law of Wages covers what families expect to need, not the theoretical bare minimums.

It is also valuable to have the option to buy a really terrible today but fine 40 years ago television for $5 (remember, down 99%!) instead of a good one for $500 or great one for $2000, or to spend $0 and use your phone or tablet you have anyway as a TV potentially better than what you used to have growing up.

A lot of the problem today is that the metaphorical cheap TV, or the option to go without one, is not available.

Consider what it would cost to get the 40-years-ago quality car, or school, or healthcare, or housing, or childcare, or even food. It is easy to forget how universally worse was the quality of most goods and services back then, of course with notably rare exceptions.

In many ways it would suck to have to, today, consume that 1984 basket, even if you got to also pick some cheap stuff from the 2024 basket like a discount cell phone and all the free internet services. But the option to go with that basket to save money, to be confident you could keep your head above water? That would be great. And also there are some places where you would happily take the discount, whereas society is forcing you to buy cars with various features, childcare from college students on ground floors and hyper expensive health insurance that has not been shown to improve health, and so on.

This is related to my thoughts on the Cost of Thriving Index, and the fact that what matters is not the CPI per se but the expected purchases you have to make and costs imposed on you, and that your practical lived experience is not going to reflect the ‘value’ of the goods purchased all that tightly.

Also related is the increasing complexity of life, and the fact that the ‘intelligence waterline’ required to navigate things reasonably keeps rising. We largely self-segregate by intelligence and it is very easy to be completely out of touch with the lived experience of the majority, and especially of a substantial minority. See this Damon Sasi thread, and the original thread from Nathan Culley.

Kimberly Strassel: Among the elite, 74% say their finances are getting better, compared with 20% of the rest of voters. (The share is 88% among elites who are Ivy League graduates.) The elite give President Biden an 84% approval rating, compared with 40% from non-elites.

I have a hard time believing that only 20% of ‘non-elite’ voters are seeing their finances improve. Here elite is defined as more than 150k in income, living in a high-density area and with a postgraduate degree, which should be a single-digit percentage of the population. Most people’s finances should be improving most of the time, since you get older and likely avoid extreme bad outcomes.

Also, the post claims these ‘elites’ have 77% support for “strict rationing of gas, meat, and electricity.” To contain climate change, you see. Support for rationing of electricity is certifiably nuts, as nuts as the ‘only four flights in a lifetime’ proposal.

When people say they believe the economy sucks for people like them, I continue to believe them. If your response is a bunch of economic statistics saying otherwise, you are asking the wrong questions.

John Arnold: 3.7% unemployment rate

3.2% annualized GDP growth

1.8% real wage growth 2023

3.1% annualized CPI

27% S&P 500 return past year

Larry Summers echoes that a lot of why people feel the economy is bad is that they hate high interest rates, because the cost of money is one of people’s main expenses. Housing is a huge cost in particular, and mortgage costs have shot through the roof mostly without coming down.

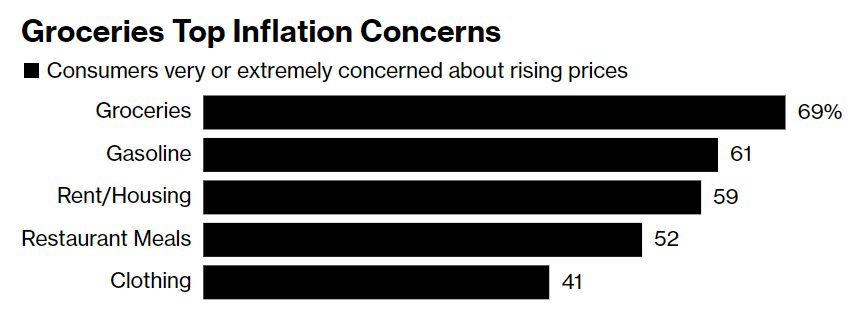

And of course people do not think about or care about the forward rate of change of the price level, they care a lot about current prices versus past prices and versus their pocketbooks, and they notice some prices more than others. So when grocery prices are up 25% in four years, that is a big deal. Everything still feels outrageously expensive, and ‘the last year has been fine’ is not yet bringing much comfort.

Nor does ‘food and clothing are actually outrageously cheap, historically speaking, you should be focused on the newly expensive things like health care and housing and education’ although that is very true.

Bloomberg: By volume, steak sales over the last 12 months were down 20% from the same period four years earlier, according to consumer research firm NIQ.

That is a very clear sign of feeling poorer, whether or not one is actually poorer. This is not about overall meat consumption or veganism, since Americans consumed 57.6 pounds of beef in 2023, down only 1% from 58.1 in 2019.

Robin Hanson points out that the best participants in prediction markets reliably outperform others, and that a market with only them would be far more accurate if they were still willing to participate and others could be kept out. Given arbitrage opportunities, this seems extremely difficult. If you could do it, though, it would totally work. The EMH is false, centrally because the market is a compromise between inertia and dumb money on one side, and smart money with its cognitive and capital and opportunity costs on the other.

So what can you do? The answer is simple. You let everyone participate, but you track who does what, and you figure out what the fair price is given everyone’s trades and track records. I have some experience with this. If you knew what everyone in market was doing, you would often say that the market price and the ‘fair’ price were distinct. There is no reason you could not also do this with prediction markets, or with the stock market.

If you know who is on both sides of every trade, and you pay attention, you can be a profitable trader indeed.

Markets are weak-form efficient if and only if P=NP, claims paper. Which we already knew, given that we knew that the efficient market hypothesis is false and also that P almost certainly does not equal NP. Now we have a claim that those two are logically linked.

Mira extends the market concept.

Mira: You should be able to buy anything with a limit order.

“I don’t feel like paying $250 for an anime figurine, but I left an order up for $50”

If they saw 10,000 orders at a lower price rung sitting there eventually they would take it. Otherwise, the demand gradient at $250 is ~0

“ebay but we virtualized all transactions so you can speculate on everything without worrying about shipping(unless you want to).

You can buy call options on your waifu’s figurine to hedge against the risk the manufacturer goes out of business and the price increases.”

The b2b version of this is “financializing the supply chain so that car companies don’t need to keep their own stockpile of parts and estimate demand to hedge against disruptions. they can buy options on necessary parts and some hedge fund will take the risk of war or sanctions”.

Kickstarter is arguably a variant of this.

As usual the answer is transaction costs, and general inability to make this sufficiently smooth and easy. Still, I do think there are many things to be done in such a space. I even have ideas about how one can use AI to do this better – you can privately indicate what you want in plain English, and then there is a background universal matching system of sorts.

The Argentinian province of La Rioja is attempting to print its own currency.

Quintela said that Bocades would be exchangeable for pesos at the provincially-owned bank. However, given the province’s scarce supply of pesos, the plan relies on “people starting to trust in the bonds’ value” so that they don’t exchange them immediately.

They want it to be one way. I am pretty sure it is the other way.

I say three cheers for most forms of surge pricing. Alas, most others disagree.

Tyler Durden (as in Zero Hedge): Wendy’s To Test ‘Surge Pricing’ Using ‘High-Tech Menu Boards’ That Change In Real Time.

“Guess people better change their lunch hours from 2pm to 4pm. With all of the concern of rising prices, the last thing you want to have to consider is how much will it cost you for a burger and fries depending on the time of day,” Ted Jenkin, CEO of Atlanta-based wealth management firm oXYGen Financial, told The Post.

Joel Grus:

Yep. There are three kinds of restaurants, those who are much cheaper at lunch, those that are closed for lunch, and those that are neither. If there was a place that gave a discount at 2pm or 3pm? I can (often) happily wait. But the places that are packed for lunch usually are, if not always as cheap as Wendy’s, also not so expensive.

In this case, the question is whether the cognitive cost and stress associated with changing prices is worth the efficiency of moving consumption to less utilized hours. My presumption is that fully dynamic pricing is several bridges too far on this, even without the public reaction, so it is good that Wendy’s backed down. There simply is not enough benefit here.

A constant discount for quiet hours (with raised menu prices otherwise), however, does seem like a good idea?

Biden Administration issues rule capping credit card late fees at $8, and according to CBS is forming a new ‘strike force’ to crack down on ‘illegal and unfair’ pricing on things like groceries, prescription drugs, health care, housing and financial services. It will never not be weird to me that people pay these fees so often, as in 45 million holders saving an average of $220 annually? Autopay exists, including to give minimum payments of similar size to the fee, life does not need to be this hard. Presumably cutting these particular fees will mean increased interest rates and less access to credit. And yes, it should scare you that the government has a ‘strike force’ aiming to target ‘unfair’ grocery prices.

Many (perhaps most) of the modern world’s trends that impact all those prices are out of government control, and that masks the quality of decisions about the parts where we can choose better or worse outcomes.

Burgess Everett: 70-25, Senate votes to disapprove rule allowing imports of fresh beef from Paraguay into the United States. That’s a veto-proof majority

Biden admin “strongly opposes” the move, which was led by Tester and Rounds

Matthew Yglesias: Everyone is mad about food prices and also hates things that would make food cheaper.

Also, yes. Everyone hates all the things that would actually make food cheaper.

Once again we confirm the finding that when you mandate transparent pay policies, as 71% of the OECD countries do, here’s what happens:

Robin Hanson: “71% of OECD countries have … [policies] revealing pay between coworkers doing similar work within a firm. … narrowed coworker wage gaps [but]… led to counterproductive peer comparisons & caused employers to bargain more aggressively, lowering average wages.”

The abstract attempts to somewhat bury the lede, that average wages are down, emphasizing all the other good effects that still combine to lower average pay to ask the title question, ‘Is Pay Transparency Good?’

Abstract: While these policies have narrowed coworker wage gaps, they have also led to counterproductive peer comparisons and caused employers to bargain more aggressively, lowering average wages. Other pay transparency policies, without directly targeting discrimination, have benefited workers by addressing broader information frictions in the labor market. Vertical pay transparency policies reveal to workers pay differences across different levels of seniority. Empirical evidence suggests these policies can lead to more accurate and more optimistic beliefs about earnings potential, increasing employee motivation and productivity. Cross-firm pay transparency policies reveal wage differences across employers. These policies have encouraged workers to seek jobs at higher paying firms, negotiate higher pay, and sharpened wage competition between employers. We discuss the evidence on effects of pay transparency, and open questions.

It is not good.

Pay transparency is even worse than that. It means that your pay must be socially determined as a function of your status and title. The equality of pay means that firms cannot pay extra to superior employees without also giving them the required social status or lifting everyone else’s pay. This not only makes them bargain harder and lowers wages, it means inefficient allocations of labor, such as when pay transparency made me unable to retain a highly valuable software engineer because the other software engineers in the company saw his pay, a small fraction of the value he produced, and threatened to revolt.

It also means that everyone around you knows exactly how much you make, which is kind of an obnoxious privacy issue, one might say. Never ask a man his salary.

Megan McArdle uses economics to argue that air travel pricing is a zero sum game. The airlines do not make real money, they will never make real money. People demand cheap airfare. The way you give it to them is to unbundle the seat with everything else, and engage in price discrimination, so if you dare say ‘families get to sit together for free’ then that generosity must be paid for elsewhere.

In which case, okay, fine, pay for it elsewhere, because that is clearly an efficient allocation and families need subsidies that won’t induce bad behavior, and not doing this increases stress on families.

Should we overall be happy that we use this price discrimination scheme, where you can fly remarkably cheaply if you accept a worse experience?

Yes, I think the optionality and ability to price discriminate outweigh the deadweight losses. I say this as someone who, although I obviously don’t have to, readily accepts the cheapest options, and accepts a slightly smaller seat in the back boarding last without a carry-on bag and so on, because I learned while being a Magic: The Gathering professional how to make that work.

The flip side is that Choices are Bad. I do not want to spend an hour stressing about exactly which features to buy for a flight, where each is priced to frequently make that decision close. I do not want to play an Out to Get You game of ‘upgrades’ against the airline, or feel like I am being threatened with potential disasters if I don’t pay up.

The ultimate version of this: Overbooked flights were always awesome, if not as awesome as having no one next to you. How great is it to suddenly be offered hundreds of dollars to postpone your flight by a few hours? When I was a Magic player I would very often take the deal, especially flying back.

The hourly rate on it was amazing even when you sold out cheap, and you could spend the time reading a book or listening to music. I love this as an example of something that some will say ‘exploits’ poor people when it does nothing of the kind, and call to be banned driving up ticket prices.

Oh, and also it seems this refers to something that happened with Uber and Lyft.

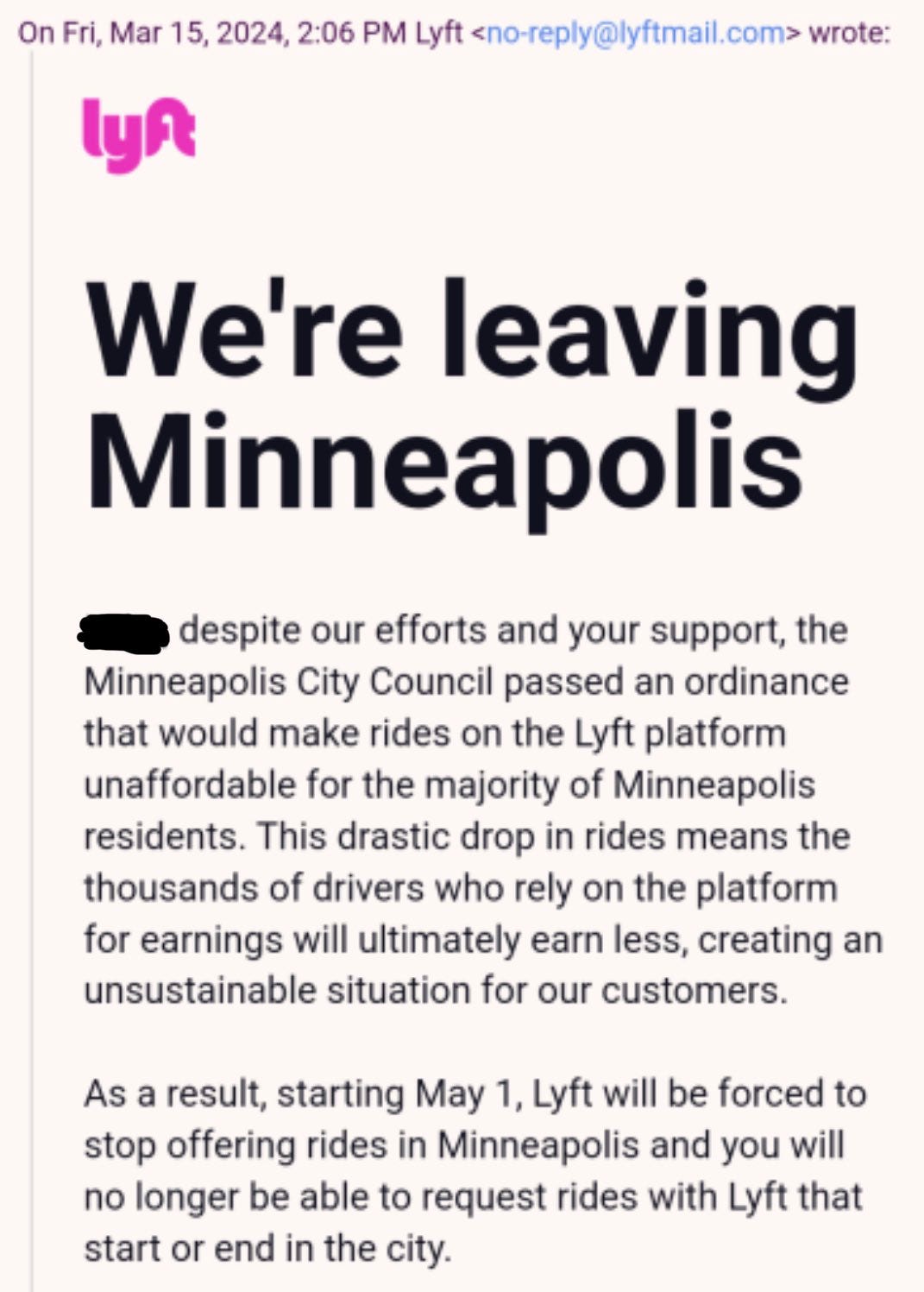

Jordan Valinsky (CNN): Lyft and Uber will stop offering services in Minneapolis on May 1 after the city council overrode the mayor’s veto of a minimum wage for rideshare drivers.

The city council on Thursday voted 10-3 in favor of the override, allowing rideshare drivers to be paid the local minimum wage of $15.57 an hour.

Lyft said in a statement the bill was “deeply flawed” and that the ordinance makes its “operations unsustainable.”

“We support a minimum earning standard for drivers, but it should be done in an honest way that keeps the service affordable for riders,” said a Lyft spokesperson.

Uber said in a statement obtained by CNN that it’s “disappointed the council chose to ignore the data and kick Uber out of the Twin Cities, putting 10,000 people out of work and leaving many stranded.”

Presumably there is then a doom loop, where demand drops so wait times increase, and because of minimum wage for down time you can’t get enough drivers standing by, so there is no viable service. Which is a shame. I am not saying I would be happy if rideshare prices doubled, but if there are no easy hailable cabs, the chances I would pay double for a given ride is substantial, especially for shorter ones.

Presumably, of course, Uber and Lyft also want to make a point and send a message to any other cities that might try this. They will survive without Minneapolis. They also would have looked terrible if they had actually doubled prices in the city, whereas they look a lot better withdrawing, the same way everyone hates surge pricing.

Paying minimum wage of $15/hour does not seem so prohibitive as to cause the doom loop. This, however, is something different.

Austen Allred: Important to note Minneapolis didn’t enforce a $15/hr minimum wage. It enforced a minimum of $1.40 per mile and $0.51 per minute (WAY higher than $15/hr), forced the companies to pay 80% of the cost of any canceled ride, and a lot more.

Robot Spider: Wait, so a 30 mile ride taking 30 minutes in medium traffic would require the driver being paid $57.30? For a half hour of work? That’s more than a software engineer.

Hktsre: wait that’s like ~$60/hour.

Joshua Hartley: The scams that 80% rule would have led to… Uber had tons of NYC scammers whenever they first were paying drivers for cancelled rides.

Then you would need to somehow pay Lyft or Uber more on top of that.

Not a reliable source, but I saw a claim that in August 2023 driver pay was $1 base fare, plus $0.20 per minute, plus $0.90 per mile.

So yes. If that is close to accurate, this jump could plausibly cause a doom loop.

It is not completely unheard of, if this discounts time between rides. For comparison: New York City yellow taxis charge $4-$6 up front, $3.50 cents per mile above 12 miles per hour, or 70 cents per minute in slow traffic (so effectively minimum 12 miles per hour in terms of payment). That is solidly more than Minneapolis is requiring.

Adam Platt breaks down what happened as he sees it in its broader context. Uber arrived in 2012, to a city without hailable cabs. Uber rapidly displaced existing very poor heavily regulated taxi service via pricing below cost and ignoring the regulations. Now the drivers are using their pull to get a 40%-50% raise by government mandate, at a level not guaranteed to anyone else, because they have political pull. Sounds right.

If the city does not back down, I do not expect Uber and Lyft to do so. We would then be about to do a natural experiment in so many ways. How much would this cause rents to drop, and how much would good locations rise in relative value?

Detroit is implementing a tax on the unimproved value of land. Tyler Cowen asks how optimistic we should be for this experiment, and brainstorms potential downsides.

One is that Detroit might use this to net raise property taxes by undoing the cut on buildings while keeping the tax on land. This is always possible but I don’t think it is likely, the two taxes are too clearly similar and correlated.

A second is that landowners might try to lower their tax burden by developing low-quality housing, whereas land speculators might otherwise be able to hold out on such low-value uses until they can do something more valuable. If the landowner is profit maximizing, we have made it more profitable to build now but even more additionally profitable to build whatever is net most valuable. Whatever a landowner who is not liquidity constrained chooses to do should be efficient? With the concern that people with negative cash flow often don’t long term maximize. But why would someone like that not simply sell the land to someone else? And in general, I find it hard to think that if this does the job of inducing more construction and more cleanup and such, that this could be net bad.

Beyond that, the big danger is indeed that this might simply not do much.

Tyler Cowen warns that new research shows that California state taxes have reached a tipping point where they are driving many high earners out of the state, erasing half or more of revenue gains, and the state is in crisis. None of that seems like news. I certainly have considered whether to leave New York for the same reason, and almost did so at one point. I ultimately decided to stay put, but I am paying a hell of a lot of money to be here.

Scott Sumner disagrees with me in the nicest possible way.

Scott Sumner: I agree with 95% of the views in this Zvi Mowshowitz post, but not this one:

Andrew Biggs makes the case for eliminating the tax preference for retirement accounts. This mostly benefits the rich, does not obviously increase net savings values, causes lots of hoops to be jumped through, and we can use the money to shore up social security instead, or I would add to cut income tax rates. This would be obviously great on the pure economics, assuming it did not retroactively confiscate existing savings and only applied going forward. But as Matthew Yglesias says, political nonstarter, so much so that not even I support doing it.

For the umpteenth time, retirement accounts (401k, Roth, etc.) do not provide any tax preference for saving. They remove a tax penalty for saving, and make the system neutral between current and future consumption.

Scott and Sumner I are thinking on different margins.

Scott’s point is that currently the tax system penalizes savings and rewards consuming now over consuming later, because it taxes income where it should tax consumption. I agree with him, and would support such a move.

However, once we have made that decision to mostly tax income rather than consumption, making an exception in particular for retirement accounts seems like a clear mistake to me given everything we now know, if we assume the revenue deficit is made up for by higher income taxes elsewhere.

Patrick McKenzie offers an additional explanation for occupational licensing, which is that it requires you to put a $X00k piece of paper, that also cost a bunch of time and energy, at risk as the price of admission to the chance of doing various crimes.

It is hard to throw someone in jail, it is hard to fine people serious money. It is much easier to take away their piece of paper. So you can keep such people on a much tighter leash.

Patrick McKenzie: One thing the IRS did was starting to assign tax preparers numbers. The biggest single consequence of this is it allows you to cluster tax fraud, which the IRS institutionally perceived as being acts of individual taxpayers, by their preparer.

…

Seen in this light, licensing regimes hear the critics of licensing regimes that suggest they are exclusionary, cost a lot of money, and teach nothing of value, and say “… And?”

They usually don’t say this out loud.

Robin Hanson: We have other much more cost-effective ways to punish offenders than this.

There are obviously much better ways to punish offenders, but in practice are we capable of doing them? Otherwise they do not help.

We have a wise legal principle that punishment legal requires high barriers in terms in terms of both burden of proof and the nature of wrongdoing.

However, in order to make many systems incentive-compatible, it needs to be possible to punish people for much lesser offenses, with a much lighter process that has a much lower burden of proof. If your homeowners association had to go to criminal court every time you failed to mow your lawn, you are not going to be forced to mow your lawn.

This suggests a simple compromise.

Let those who would enter the profession have a choice. They can choose to go through the training and licensing process as it exists today.

Or they can choose to post an actual bond for $X00k, perhaps via insurance. If something goes wrong, you have now agreed to forfeit some or all of that bond via a much lighter process with a much lower punishment threshold than the courts.

To be clear, regardless of the alternatives, this is all a deeply stupid reason to throw up huge barriers to people doing useful things. There are indeed many obvious superior solutions. But you do have to deal with the problem that this is helping to solve. This might beat doing nothing, given the brokenness of our default systems.

Claim that workers are much more productive outside the office, to the tune of £15,000 per worker per year for every extra day (I assume of the week). That is an absurd amount of extra productivity. This seems difficult to reconcile with the additional finding that return-to-office orders had almost no effect on profitability or market value.

The current best theory seems to be that on a given day productivity is often better at home, but that you learn skills, build a team and coordinate better at the office, so the costs of remote largely only show up over time.

Patrick McKenzie promotes Mercury as much better than other banks for wire transfers, with routine payments landing in under a minute.

Patrick McKenzie’s Bits about Money, Financial Systems Take a Holiday, all sorts of annoying persnickety and fascinating (to me anyway) details. Incidentally, such issues will keep the AIs away until suddenly they don’t.

Also his periodic reminder that the things said by customer service representatives at banks correlate remarkably little to what would happen if you wrote the bank a letter from a Dangerous Professional (or got Claude to write it for you), especially when what the CSR says is not in your favor.

The rules for checks are illegible and complex, because illegible and complex rules refined over decades perform better, and as a legal system checks get to keep those rules.

Claims about FTX and Alameda and Tether, that they were engaged in highly systematic money laundering and it is only now starting to come to light and we have only seen the tip of the iceberg. It certainly is hard to reconcile the facts presented with these companies not being a blatant criminal conspiracy in distinct ways from the stealing of customer funds.

Nate Silver: Average monthly price of top 10 paid Substack newsletters, selected categories:

Culture: $6.50

US Politics: $6.60

Sports: $8.10

Business: $22.90

Tech: $28.50

Finance: $45.00

Yes, we’re spending our Saturday afternoon doing a little Market Research™. Silver Bulletin is weirdly like 20% sports-ish, 60% politics-ish and 20% biz/tech-adjacent so it’s kind of a weird one. Big year ahead so I hope you’ll consider reading.

This would suggest I am underpricing at $10, since my comparables are all over $20, usually for a lot less content. But of course those Substacks mostly paywall their content, whereas I paywall absolutely nothing. So the value proposition is in that sense not so great. The $0 deal is, from one’s own perspective, even better. Still, what a deal.

Vitalik Buterin offers thought on ‘the end of my childhood,’ which is more of a wide-ranging survey of what he has learned and how he has changed, with childhood’s end being the taking of responsibility for being ‘one of the others’ who works to make things better.

Offered without comment, except that of the places I’ve worked with others (as opposed to communities, although it is still close) I find the same:

Jim Savage: A friend who worked for startups, nonprofits and the top rungs of government now works for a hedge fund. Calls it the most truth-seeking place she’s ever worked. Interesting how humans thrive when performance is a scalar.

In defense of the Ferengi and the need for markets in Star Trek’s Federation. Akiva Malamet points out that the Federation has turned so far away from markets that it is horribly inefficient at resource allocation and unable to do business where there is not abundance. Earth may be a paradise in Star Trek in many senses, but labor and what is effectively capital are allocated horribly, and the incentives do not work at all. I would add that Starfleet is horribly inefficient as well. Humanity fights existential wars on a regular basis, and no one thought to have a dedicated warship until the Defiant, instead we thought with the same ships we use for trade and exploration? We send gigantic ships to explore strange new worlds when we could send a scout ship, or an unmanned probe (even if you buy random just-so limits on AI)?

Meanwhile yes, things mostly don’t seem great for Ferengi or on Ferenginar, and the author admits there is far too much greed for greed’s sake (and of course the writers give Ferengi many negative attributes not related to being capitalists), but they can get things done. Most of the things shown as wrong with Ferengi society are not actually economically efficient. That they have not long since been eliminated tells you a lot about how that society actually works.

Scott Sumner on China’s weak economy. It does make sense that if youth unemployment is 20% and there are plenty of workers in the countryside, then the impending demographic collapse is not yet an issue, except perhaps for real estate prices. It will bind eventually, but not yet.