This post brings together various questions about the college application process, as well as practical considerations of where to apply and go. We are seeing some encouraging developments, but mostly the situation remains rather terrible for all concerned.

Paul Graham: Colleges that weren’t hard to get into when I was in HS are hard to get into now. The population has increased by 43%, but competition for elite colleges seems to have increased more. I think the reason is that there are more smart kids. If so that’s fortunate for America.

Are college applications getting more competitive over time?

Yes and no.

-

The population size is up, but the cohort size is roughly the same.

-

The standard ‘effort level’ of putting in work and sacrificing one’s childhood and gaming the process is dramatically up. So you have to do it to stay in place.

-

There is a shift in what is valued on several fronts.

-

I do not think kids are obviously smarter or dumber.

This section covers the first two considerations.

Admission percentages are down, but additional applications per student, fueled by both lower transaction costs and lower acceptance rates, mostly explains this.

This means you have to do more work and more life distortion to stay in place in the Red Queen’s Race. Everyone is gaming the system, and paying higher costs to do so.

If you match that in relative terms, for a generic value of ‘you,’ your ultimate success rate, in terms of where you end up, will be unchanged from these factors.

The bad news for you is that previously a lot of students really dropped the ball on the admissions process and paid a heavy price. Now ‘drop the ball’ means something a lot less severe.

This is distinct from considerations three and four.

It is also distinct from the question of whether the sacrifices are worthwhile. I will return to that question later on, this for now is purely the admission process itself.

The size of our age cohorts has not changed. The American population has risen, but so has its age. The number of 17-year-olds is essentially unchanged in the last 40 years.

GPT-4 says typical behavior for an applicant was to send in 1-3 applications before 1990, 4-7 in the 1990s-2000s, 7-10 in the late 2000s or later, perhaps more now. Claude said it was 3-5 in the 1990s, 5-7 in the early 200s and 7-10 in the 2010s.

In that same time period, in a high-end example, Harvard’s acceptance rate has declined from 16% to 3.6%. In a middle-range example, NYU’s acceptance rate in 2000 was 29% and it is now 12%. In a lower-end example, SUNY Stony Brook (where my childhood best friend ended up going) has declined from roughly 65% to roughly 44%.

The rate of return on applying to additional colleges was always crazy high. It costs on the order of hours of work and about $100 to apply to an additional college, and the common app lowers that further. Each college has, from the student’s perspective, a high random element in its decision, and that decision includes thousands to tens of thousands in scholarship money. If you apply to a safety school, there is even the risk you get rejected for being ‘too good’ and thus unlikely to attend.

Yes, often there will be very clear correct fits and top choices for you, but if there is even a small chance of needing to fall back or being able to reach, or finding an unexpectedly large scholarship offer you might want, it is worth trying.

As colleges intentionally destroy the objectivity of applications (e.g. not requiring the SAT, although that is now being reversed in many places, or relying on hidden things that differ and are hard to anticipate) that further decreases predictability and correlation, so you have to apply to more places, which forces others to follow and creates a doom loop.

This process should accelerate even more. Not only is there a doom loop already in place, ChatGPT and other AI services (right now I would use Claude Opus here) are dramatically lowering the time cost of a good marginal application. Whether or not you spend a lot of time on your top picks, if you are not also flooding the zone, why not?

Also, outside of early admission, your time figuring out your true preference order is much better served after you know who will accept your application and what deals they are offering, rather than before. You will have so much better information then, and the ability to automatically exclude most of the possibilities.

This was my personal experience as well. Once I saw where I had been admitted, there was no choice at all. The rank order was obvious. In other scenarios I would have had a decision to make, but I got to skip that question entirely.

Note that this remains true no matter your priority order. If different schools may or may not admit you or give you a good aid package, apply now, sort it out later.

This all goes double now that you can use AI help to lower application time costs. My model is the majority of students were severely underapplying before ChatGPT, even more severely underapplying now, the gap will rise over time, and that this mistake is expensive.

There also seems like little reason not to use early admission, which is currently used only about half the time. If you have a clear first pick among plausible choices, then presumably you pick there. If you do not, and don’t have anything else you are using the slot on, then you might as well try for a reach. Even a 1% shot at MIT or Harvard is well worth it if you didn’t have a better play. Another good reason to apply early is that this is insurance against something happening that trashes your application’s quality.

I see two reasons not to apply early. The first is that you think your applications will be much stronger with the delay, due to new evidence you can cite, so much so that even your reaches are better off with the delay. Seems rare. The second is if you are close enough between several candidates where you expect to be admitted that scholarships and final cost are the key factor, so you need to see everyone’s offer.

As noted above, kids are getting smarter about admissions. They are doing a lot more strategic behavior with the goal of getting in. Are kids getting smarter over time more generally, beyond many putting in more effort to game the system?

My answer is no. My best guess is that kids are about as smart as they used to be on net. Some aspects improved, some got worse. What they can do now is much better access and share information and play the games they are forced to play at the expense of actual games they would want to play, the same as everyone else.

Someone like Paul Graham or Tyler Cowen is noticing more smarter kids, because we now have much better systems for putting the smarter kids into contact with people like Paul Graham and Tyler Cowen. They have better opportunity especially in non-traditional paths.

Indeed, from what I see there is consensus that academic standards on elite campuses are dramatically down, likely this has a lot to do with the need to sustain holistic admissions.

As in, the academic requirements, the ‘being smarter’ requirement, has actually weakened substantially. You need to be less smart, because the process does not care so much if you are smart, past a minimum. The process cares about… other things.

I think this is the main reason getting in seems harder, especially to smarter kids.

From what I can tell, there are two highly related dramatic changes in admissions criteria. Both make it harder for ‘purely’ smart students to get into a good college.

The first is the shift to ‘holistic’ admissions, and the quest for kids who are ‘well rounded’ and who display various other desirable attributes and signals.

As mentioned already, the holistic admissions process is less predictable, feeding into the doom loop in applications, but that is not the main issue.

The main issue, as the next section tackles, is that its hunger knows no bounds. The race has no limits, it will eat your entire childhood.

For someone like me, or I am guessing most of you, this is ruinous.

It is ruinous for my chances of getting in, even if I play the games. But also it is ruinous for my childhood, unless I am willing to opt out entirely, and take an even bigger hit than the unavoidable one. I do think the opt out is mostly wise.

For others, it means they are in game on a much higher level. For better and worse.

I think this is a no-good, very bad shift in priorities. Of course I am biased.

The second is far more determined efforts to outright discriminate, whatever you think about such efforts.

This obviously makes admission into any given school much harder for anyone who is on the wrong end of the discrimination.

Holistic admissions are a great idea under two key conditions.

-

The new metric is a superior measure when not twisted.

-

The applications are not twisting their whole lives to game the metric.

It is plausible to me that consideration #1 is true. Alas, #2 is true no longer.

So when we ask what is going on with what look like completely insane efforts to get kids into college, why is that happening? Well, we all know the answer to this, don’t we?

T. Greer: Everything in this article… the hopes of the kids, the ambitions of the parents, the schemes of admissions whisperers… just makes me so sad. This is not the way.

I saw this culture, participated in it, when I lived in China. I condemned it as wicked. But the gap between the Chinese and American striving classes erodes every year.

How can this be stopped?

I am serious. What, practically, can be done to stop this? What are the steps?

Tracing Woodgrains: an admissions system that persuades people to structure their whole lives around it is profoundly inhumane

people who celebrate holistic admissions should remember: what a system can consider, it can control

if an admissions system can consider a person’s whole life…

Emmett Shear: I might even go farther and say, “what a system can consider, it will attempt to control.”

The NY Magazine article linked points out that admissions is hardest when making between about $150k and $250k a year, because at that point you don’t get any benefits from being poor and also you aren’t rich enough to bribe and manipulate the system (including for free via being a plausible future donor), or in many cases even afford the tuition on which you will get no discounts.

Another issue is that this group will shop aid packages and make rational decisions, whereas colleges want to juice the rate of admitted students attending, so outside of early admission they are a ‘bad risk.’

According to the article, the rich advantage breaks down into this:

20% due to higher application rates.

12% due to higher attendance rates when accepted.

About 50% due to legacy status, which is a ~5x multiplier.

25% due to athletics, and ability to train in rich person sports.

31% due to being ‘judged stronger on non-academic categories.’

(Missing: X% due to superior academic performance.)

(Implied at least (X+28)% handicap from other factors, or this doesn’t add up.)

Added the last one because I notice this adds to 128%. That is (I presume) because these children also face severe smackdown for their backgrounds in other ways. There are stories of parents moving to Ohio or Florida to try and mitigate such smackdowns. Other aspects are unavoidable.

The 128% here also excludes being able to get superior academic evaluations, by posting superior academics, via a variety of methods, however you think of that.

What can be done about this dynamic, where the admissions process plus tuition eats all family resources and kids entire lives unless they are well into the 1%, and everyone who opts out of this falls quite far in where they can go to college relative to if they had participated?

I see three ways out.

-

The elite universities could continue burning their reputations to the ground sufficiently, combined with technological change, that there is not enough of a prize left to be worth fighting to get. If Ivy+ institutions no longer have demand vastly in excess of supply, at least at full tuition rates for students who can actually handle the coursework, you can relax.

-

Your family can opt out anyway, noticing that the price of this game is already not worth paying. This is my plan. The game is rigged, but no one forces you to play. By the time my kids are ready to consider college, you will not need college to learn, nor do I predict that such a degree will be needed for what they will want to do, even in relatively normal-looking ‘AI Fizzle’ worlds.

-

We can severely collectively restrict what (at least some) colleges are permitted to consider in the college admissions process.

I would vote for option number three, and will fall back on number two. It is a big lift from where we are, but with a sufficiently strong will to do it there is no reason it could not be done. Every statistical study shows that admissions purely on the basis of relatively objective criteria such as the SAT, would give richer applicants a smaller advantage than the current system.

We could adjust or not adjust for specific other factors as desired. You could also include a carve-out for a small number of slots that could be given out under truly special circumstances, sufficiently special that a typical student can’t aspire to them.

I also continue to support auctioning off a few slots. It is a Pareto improvement.

Meanwhile (almost) everyone gets their lives back.

What else does the alternative imply?

Paul Graham: The more arbitrary college admissions criteria become, the more the students at elite universities will simply be those who were most determined to get in.

Sudhir Nain: So is that a good thing or bad.

Paul Graham: On the whole bad.

I can think of worse systems than ‘who wants it more’ if you have a reasonable way to measure who wants it more. If the way you measure is largely who burns more of their lives trying? That is not as great. And the idea that ‘wants it more’ will dominate ‘has money to spend or other resources to help get it’ in the arbitrary criteria Olympics seems dubious at best.

To summarize the model of the application process itself so far: I model the big changes in college admissions, especially near the top, not as increased quality and quantity of real competition, but as a combination of:

-

A real shift in what factors get how much consideration, making things easier for those who have or can get or fake the required attributes and harder for everyone else.

-

Less advantage for ‘realizing you should apply to more places’ because everyone does it.

-

A lot of extra applications that mostly have no chance of acceptance or almost no chance of being utilized, and don’t change things much except the reported numbers.

The question is mostly how to think about (1). I do think it would be harder for me in particular to get into an elite college now, due to this effect, but that has little to do with overall difficulty and more to do with colleges valuing me less and others more.

Similarly, an inconclusive argument that college admissions are less competitive is that the number of elite college slots per high school graduate has increased. Even if you exclude questions of foreign students applying, this tells us little about the lived experience and chances of an actual applicant, even once we confirm that high school graduation rates are not doing anything weird. We need to know how many of those slots are ‘live slots’ that aren’t reserved in some way, we need to know how much effort is being put towards the elite slots. Also most of us should care far less about the true elite slots than we do about the tiers below them.

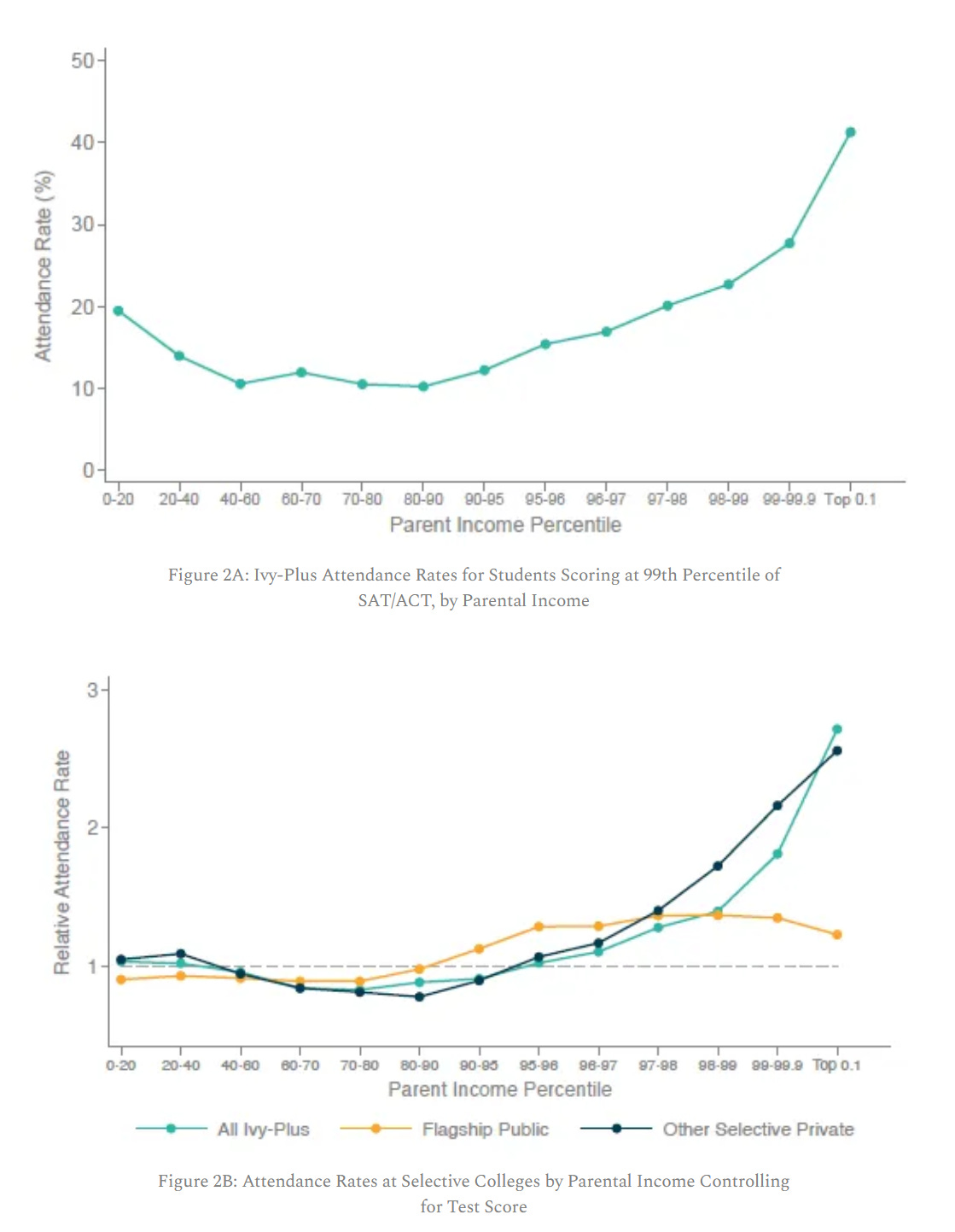

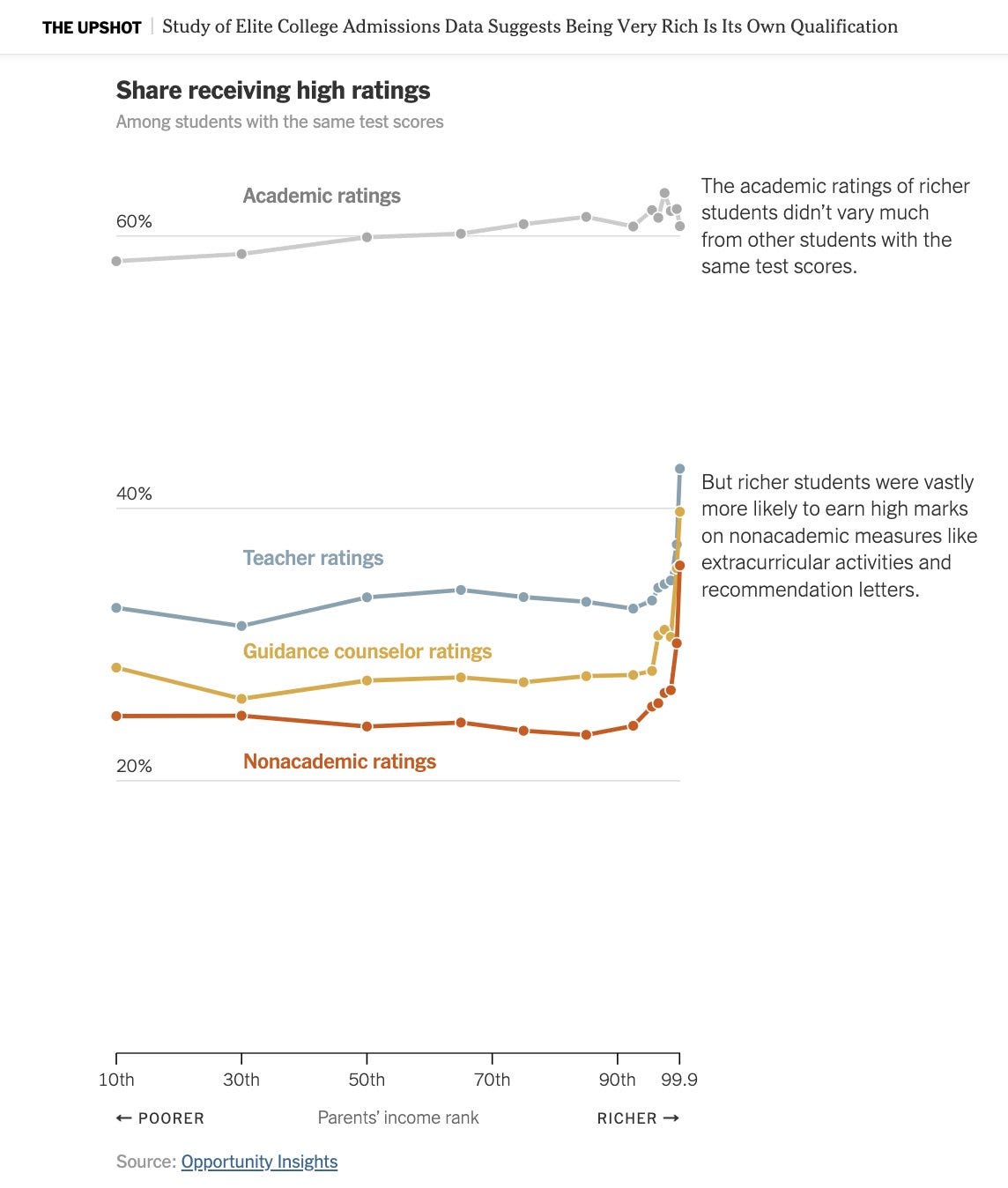

Meanwhile elite colleges are responding to the shifting policy regime that includes a ban on explicit affirmative action, and their own incentives, by shifting ever-more away from objective measures like SATs and GPAs, and towards intangibles that greatly favor the super rich. The NYT covered this here on the high end, based on this paper, which notes that being from a highly rich family is a large advantage in Ivy+ college admissions when controlling for SAT scores (and the fact that you would control for this is a hint).

Note that being merely well-off does not give you an advantage. Indeed, quite the opposite, you get to pay a lot more money and get the product no more often. It is only around the 98th percentile that you get much effect, and the major effect is confined to the top 1% or even 0.1%.

Forked Lightning’s David Deming (an author of the paper): The question is, why? Do rich kids apply to Ivy-Plus colleges at higher rates? Are they admitted at higher rates? Or once admitted, are they more likely to accept the offer, perhaps because they don’t need financial aid?

The answer is yes to all three, but it’s mostly admissions. We estimate that about 2/3 of the “extra” rich kids at Ivy-Plus colleges are there because of preferential admissions practices.

…

Three factors explain almost all of it. The biggest chunk – about half – is preferential admission for legacies. Legacies are richer than the average applicant. Also, the legacy admissions boost is greater for high-income legacy applicants (see Figure 7b). The second factor is recruited athletes. Again, athletes are richer than average Ivy-Plus student, and they comprise 10% of the total class at such colleges, compared to 5% or less at large public universities.

The third factor is that rich kids receive systematically higher “non-academic” ratings.

The solution to fixing this, if you want it fixed, is to put greater focus on academic considerations, especially standardized test scores including things like AP exams, that are objective and harder to game or buy. We are seeing some ‘coming back from the brink’ on this, but not the kind of shift that solves the problem.

Also helpful are things like this: Caltech drops calculus, chemistry and physics class requirements for admission. I was ready to be deeply sad at the vanishing of some of the few real standards left. Then I realized they didn’t drop the calculus, chemistry or physics requirements. They will, as an alternative, accept evidence of actual knowledge of calculus, chemistry and physics. You can satisfy this with Khan Academy as verified by Schoolhouse, or a 5 on an AP exam. If anything this does not go far enough. A class is no substitute for knowledge.

NY Magazine profiles a high end Ivy admissions consulting firm. 190 clients pay $120k each year, in exchange for 24/7 access to an Ivy league alumni, they claim high success rates but no one knows let alone knows the counterfactual. Pay for the alumni is $50k-$70k base with up to $200k bonuses for getting students in, very good incentives.

The amazing extra note is that students who fail early admission can buy a $250k two week intensive unit to ‘get their regular-decision applications in fighting shape.’

Via Alex Tabarrok, Lloyd Cohen offers a taxonomy of different discrimination methods, reformatted a bit for readability, note this is 20 years old:

Not all procedures for engaging in racial discrimination are equal. They differ in their legal standing, their social meaning, and their “economic” efficiency. The Supreme Court in distinguishing Grutter and Graatz, and the admissions regimes of the various state universities suggest a useful taxonomy.

There are three generic forms of racial discrimination not merely in admissions decisions but in other practices and policies as well:

Express and objective (i.e., points and quotas)

Facially neutral and objective (e.g., the top 10% of graduates from each high school)

Implied and subjective (“we look at the whole person”).

From an efficiency perspective the first form of discrimination is the least harmful. It does not corrupt the measure of merit, it only sets a different standard for “minorities.”

Its shortcomings are twofold. First, as the Supreme Court decisions in Grutter and Grattz makes abundantly clear it is the one method most likely to be found illegal.

This is implicitly related to its second shortcoming, it is so barefaced. It makes clear to both those favored and those harmed that the favored are otherwise inferior in their qualifications.

The second method, using a facially neutral operational measure to achieve a suspect theoretical goal, now favored by the state universities of California, Texas and Florida, in granting admission to those who finish in the top X% of their high school class and by the United Network for Organ Sharing in granting more “points” in the organ allocation scheme for time on the waiting list, has the virtue of being an objective measure, and the virtue (?) of a disguise that reduces shame.

Its shortcoming is that its effectiveness in bringing about the preferred ethnic distribution is tied to its inefficiency. It employs an objective measure of merit that substantially distorts. Thus, the rankings of both the favored and the unfavored groups are misaligned.

The third measure, a subjective, ad-hoc eclectic judgment, can in practice be a mimic of the first, the second, or anything else. The process becomes a beclouded mystery. This is both its virtue and its vice. There is no clear trail, evidence or standards that mark the favored as inferior–feelings are spared. On the other hand the absence of an objective measure means that the decisionmakers are effectively unanswerable and may indulge in any form of corruption.

Method (1) is clearly falling by the wayside. Is there likely to be a clear political winner between (2) and (3)?

As you would expect, I strongly favor (1) over (2) over (3), with (3) being far, far worse for ‘eating your whole childhood’ reasons. Do, or do not.

If we decide we cannot support doing (1) we also shouldn’t do (2) or (3). But if ‘we’ are divided, as we are, and ‘because of reasons’ (1) is off the table, then I vastly prefer (2) to (3).

The question on (2) is how distortionary it is, and in which ways.

If families mostly do not respond to the resulting incentives, then (2) should mostly be fine. You are in important senses ‘choosing the wrong’ applicants, but also you can be addressing multiple goals, aiming to also discriminate by geography, economic class and circumstances for their own sakes. It will not be perfect, but it will be fine.

Also, most students who get their ‘top 10%’ ticket via geography end up turning it down. Many know they are not ready, others simply cannot imagine the path. This has its advantages – it means you can offer admission to many more students than you could with a better fit path.

What about if (2) causes major distortions? One could think that this kind of strong incentive for other forms of diversification is wonderful. One could also think it is hugely distortionary, costly and bad. And one could worry that this would make getting in without such tactics prohibitively difficult for everyone else if this process takes off.

The ideal admissions policy for a state school is presumably to expand your size sufficiently that you can admit everyone who could plausibly succeed at your school. At that point, discrimination on admissions would be pointless, you would be actively hurting the additional students you admit. Instead, if you wanted to discriminate, you would discriminate with scholarships. The problem, like other admissions problems, only arises if you have far more students who can hack it than you have slots.

If admitting everyone who could benefit would not solve your true goal, then you would need to stay smaller than that and perhaps also lower your standards, but I would then assert you have the wrong goal.

Alas, if the law says (2) is no good, then in practice (3) it is. We await SFFA v. Harvard.

I am very happy to see the return of standardized testing.

As Alec Stapp puts it: Sanity is returning, nature is healing, as more schools including MIT, Dartmouth and Yale once again require the SAT, this link covers Dartmouth. CalTech did the same, after previously disallowing all test scores of any kind. That MIT in particular did away with standardized tests, even briefly, still makes me shudder.

As may point out, the SAT (or ACT) is by far the most egalitarian option we have, the closest thing to a level playing field. And while yes you can cram and prepare for it, doing so is far less destructive, time-consuming and soul-crushing, and far more optional, than optimizing other parts of your application.

Dan Riffle: My mom was a Red Lobster waitress. I never met or got child support from my dad. We moved a lot, so my teachers/counselor didn’t know me. I waited tables and loaded UPS trucks at night, so my grades sucked and I had no extracurriculars. Acing the ACT was my only shot at college.

Matt Bruenig offers a personal case for college admissions exams, noting it was his way in, making the usual (true) case that exams are far less biased against the poor.

Jay Van Bavel points to this analysis that essay content has a higher correlation with household income (R^2 = 16%) than SAT scores, based on 240k admissions essays.

It is very difficult to game the SAT and other similar tests. You can get tutors and specialists and yes they help a modest amount, but that tops out fast. Whereas every other rating measure we have that is not a standardized test or an explicit discrimination schema is much, much easier to game.

I note that he claims there is obviously no difference between the 90th percentile and 99th percentile college applicants, which is very obviously not true.

What happened to students who were admitted without checking their SAT or ACT scores? University of Texas ran the experiment and found out.

Max Meyer: University of Texas data dump on test-optional students. I’ve been waiting for this! Ivies will never publish out of embarrassment, but UT did.

Test-optional admits had a first semester GPA 0.86 points lower than those who submitted SAT/ACT. A whole grade!

The median SAT of those who asked not to have their score considered for admission was nearly 300 points lower than those who wanted them considered (1160 vs 1420). That’s more than a standard deviation!

I will be really curious to see what the 5-year GPA chart for 2020-2024 looks like compared to the one above, 2015-2019.

The whole movement toward test-optional has been funny but it should really be over now.

Kitten poster: Let me further clarify I did terrible on SAT but passed AP physics b, calc ab, AP us history, ap biology , AP English all with 4s, with history a 5. Does this mean my ability sucks compared to the skater who dropped out after the first semester that had a higher sat?

Zlinsky Silverwords: Apparently you didn’t study Statistics.

It is good to confirm the obvious. If your score is good you opt in, if it is poor you opt out, that is how this will work. So there will be a huge gap in scores, here 260 points. It does not seem so surprising to have that translate to 0.86 in GPA. My guess is this gap is mostly driven by the students well below 1160, where the bottom falls out because they simply cannot handle courses at this level.

It does tell us that the holistic other considerations did not correct for the problem. We did not see otherwise much stronger candidates emerge from the non-test pool.

Tracing Woods wrote an extensive commentary on this, pointing out various obvious things, but it got deleted.

James Kim (responding to Woods): Former admissions officer here — this is all spot on. None of it is controversial _within_ admissions departments either; they just can’t say it publicly because the demographic reality is deeply uncomfortable and politically incorrect.

There’s one other reason for mandating tests that is strictly pragmatic. When colleges went test-optional, they started receiving 1000s of “throw my hat in the ring”-style apps that they still had to review in order to disqualify. It’s been making my former colleagues miserable.

This thread is starting to do numbers, so let me state for the record that I have nothing but respect for my former admissions colleagues, who do the best they can in the face of conflicting institutional priorities and their personal convictions. It’s a tough and thankless job.

Oh. That. Yeah, that was rather inevitable. If you are not being ruled out by default, why would you not spray and pray even more than before? And now when they do that, you cannot take one look and reject, you have to do the work, and every so often you will screw up. If there are no hard numbers, the correct answer to ‘where to apply’ rapidly becomes rather similar to ‘actual everywhere you would want to go.’

When they discontinued the SAT, many schools also threw out the GRE. The fight continues to undo that mistake as well.

Steven Pinker is trying to get the GRE reinstated at Harvard. So far no luck. He notes that the Ivy+ applicants are heavily favored without the GRE, because they get tons of applications and have no good other way to filter. Steve Hsu here raises the same point about CalTech.

I expect more similar things as AI allows applicants of all sorts to flood the zone. If you are getting lots of low-quality low-cost applications, that means you will look for signals that are hard to fake and easy to evaluate, that you can use to narrow the field.

Another problem is the continued neutering of many tests. Starting in August 2024, LSAT to eliminate the Logic Games (Analytic Reasoning) section, the hardest, most fun and most objective and intelligence-testing part of the whole test. Normally I would be against dumbing down our testing, but keeping smart people from becoming lawyers is not the worst idea.

Tyler Cowen argues against banning legacy college admissions. His framing seems unstrategic, framing it as the right-wing principle that growing university wealth enables innovation and wealth creation, ultimately benefiting everyone. Why must selling a quality product be inherently right wing?

Without legacy admissions, selective colleges would be a worse product that would make vastly less money.

-

The legacies provide networking.

-

The promise of a legacy makes admission far more valuable.

-

The promise of a legacy is a key reason people donate.

-

This together allows allows massively more fundraising.

-

This also ensures loyalty and school pride, the building of traditions.

The rich are buying a mix of a luxury good and a positional good, at prices vastly greater than what that good is worth to others, who have fine alternatives. We use that money to fund education and research, and to sell others contact with those rich folks.

Unless you believe the entire elite university system is so corrupted you want it destroyed (and I can see why one could think that), why not let the rich buy?

We will test this theory now that Virginia has banned legacy admissions in public universities, if they enforce it statistically, which seems difficult. If I have to choose between the University of Virginia and a similar rival, why wouldn’t I want there to be a place my future kids have a leg up?

This does not rise to the level of ‘pay out-of-state tuition to avoid it.’ But if I was considering going out of state already, going to Virginia got a lot worse.

Alternatively to the plan to end legacy admissions, one can propose replacing legacies with an action system, as suggested by Nate Silver above. This has a lot of the same effects. You don’t have to buy a slot for your kids at the same place you attended, but a lot of people will anyway.

Nate Silver suggests two proposed admissions modifications.

Nate Silver: If you put me in charge of an Ivy League school I’d auction off 10% of the admission slots to the highest bidders (you’d graduate with a scarlet ‘A’ on your diploma for Auction) and determine the remaining 90% by lottery among all reasonably qualified candidates.

I like the idea of auctioning off 10% of the slots. As many have noted, being around the rich is part of the product, plausibly the very rich get higher marginal returns to attending. And we want to encourage elite participation and provide a strong incentive for people to earn more and then return that money to society, and to do that in an open and honest way rather than via tax deductible ‘donations.’

It’s also smart price discrimination. That 10% then subsidizes the other students, who plausibly can now go for free.

You could require that the students meet a minimum standard, where they could plausibly succeed. Or you can say why cares, caveat emptor, if you buy your way in and then fail out that is on you. I would understand the first approach, but if given the choice I would go for the second one.

Indeed, I get the appeal of the scarlet A, but you can probably raise a lot more money if you get rid of that. The product would be a lot more valuable.

Another way to see this is that either you can auction off 10% of the slots, or you can do what we are doing now, which is to charge 100% of students a much higher tuition cost, often to the point of taking everything their family has and loading them with debt on top of that, and letting a few mitigate this by working the scholarship system.

That seems way worse for everyone.

Yes, in the new system a few students get demoted a notch in terms of where they go, but those students save a lot of money.

Consider also the current phenomenon of the ‘non-elite private’ schools, where tuition is super high and economic returns look terrible. These schools are effectively allocating most of their slots via auction, which does a similar thing inefficiently while reducing elite participation and contact with others.

What about the lottery for the other slots? There I am far more skeptical.

Yes, there are ten times as many people who would be reasonable Harvard picks as there are slots for them. Perhaps far more than ten.

That does not mean all those applicants are created equal.

You would get a lot of students ‘coming out of the woodwork’ and flooding the zone with applications, with the new lower bar of getting into the random admissions pool.

It also means, if the Ivies all did this, that you would essentially be forcing everyone who can pass the Ivy bar to apply to all of the Ivy schools, and then they go wherever they happened to land, and then additionally applying all over again to other schools for the scenario where all their Ivy lottery tickets miss.

Anyone who can’t do this gets punished. Students don’t get to choose where they prefer to go. Also colleges now can’t much compete for individual students, so they won’t offer the good ones deals. That all does not seem great?

Worse, if you have specific criteria (for example, sports teams you want) then you either have to make an exception that then forces everyone who cares down such paths, or roll the dice and risk utter disaster. Also doesn’t seem great.

And of course, if you do random admissions above a threshold, and others don’t, the adverse selection is brutal. If you’re a reach they accept every time. No one applies to you early admission. And so on.

You also greatly increase the variance from the school side, and the number of kids that get taken off of (also randomized) waiting lists. The law of large numbers helps somewhat, but there will be lots of students where whether they accept the offer is random because it depends on the result of other lotteries. Which also means that tons of students will spend months with some chance of getting a last-minute change of venue, which then cascades.

A top priority is keeping things simple. So you don’t want to do some monstrosity of a four-category three-step system that I designed in my head right now to solve a bunch of problems. Then again, the current system is super complex under the hood, and forces students to do very complex strategic games without knowing the rules?

The obvious solution if you wanted to go down this path, if it was permitted by law for the schools to coordinate this way, would be a common Ivy (or ‘elite’) application, matching system and lottery.

-

Each student enters a rank order of the elite schools they are applying to.

-

Each school either accepts into the lottery, or rejects, each student.

-

Schools can coordinate on that decision to the extent their thresholds match (so for example my presumption is that if you can hack it at Princeton you can mostly hack it at Yale and vice versa, but MIT should care about somewhat different things if it is participating.)

-

-

Students have their order randomized by lottery.

-

You go down the list of students, each one is placed at their top choice that has at least one open slot. Presumably mostly Harvard fills up, then Yale, and so on, but if someone has different preferences they get what they want.

-

Students who get at least one acceptance but no match get a certificate of this, which other schools can choose to consider, or accept as an automatic admission.

I initially thought that a matching system would not work because it was not reasonable to ask students to rank all the schools prior to application. That is a cost, but I have reconsidered this for a few reasons.

-

The marginal rank order is not that important. If you rank X ahead of Y and are 10% to get into both from lottery alone, at most 1% of the time does not matter.

-

If you get it wrong, you are probably making a small mistake.

-

There is a reasonably public and consensus rank order to use as a default, it would be reasonable to enter that order without thinking about most of it.

I do not think a lottery is a good idea. But if you did one, that is how I’d do it.

Why are there far more women than men in college? Could it be that the system systematically favors girls over boys? That school as currently instantiated is a highly non-neutral world, in which the natural behaviors of boys are considered bugs to be fixed, where bias is only ever allowed in one direction and not the other, and that evaluates them on the basis of age when their development is periodically behind, and so on?

Back in 2022, the St. Louis Fed claimed that no, it is because women enjoy greater labor market returns to college than men.

One potential reason that could explain this trend is a similar one in the relative academic performance of girls versus boys at the high school level. If girls are increasingly outperforming boys in high school—whatever the reasons may be—it would make sense that they would increasingly outnumber boys in college (although this would not imply causal influence). If this were the case, we would delve into those underlying reasons.

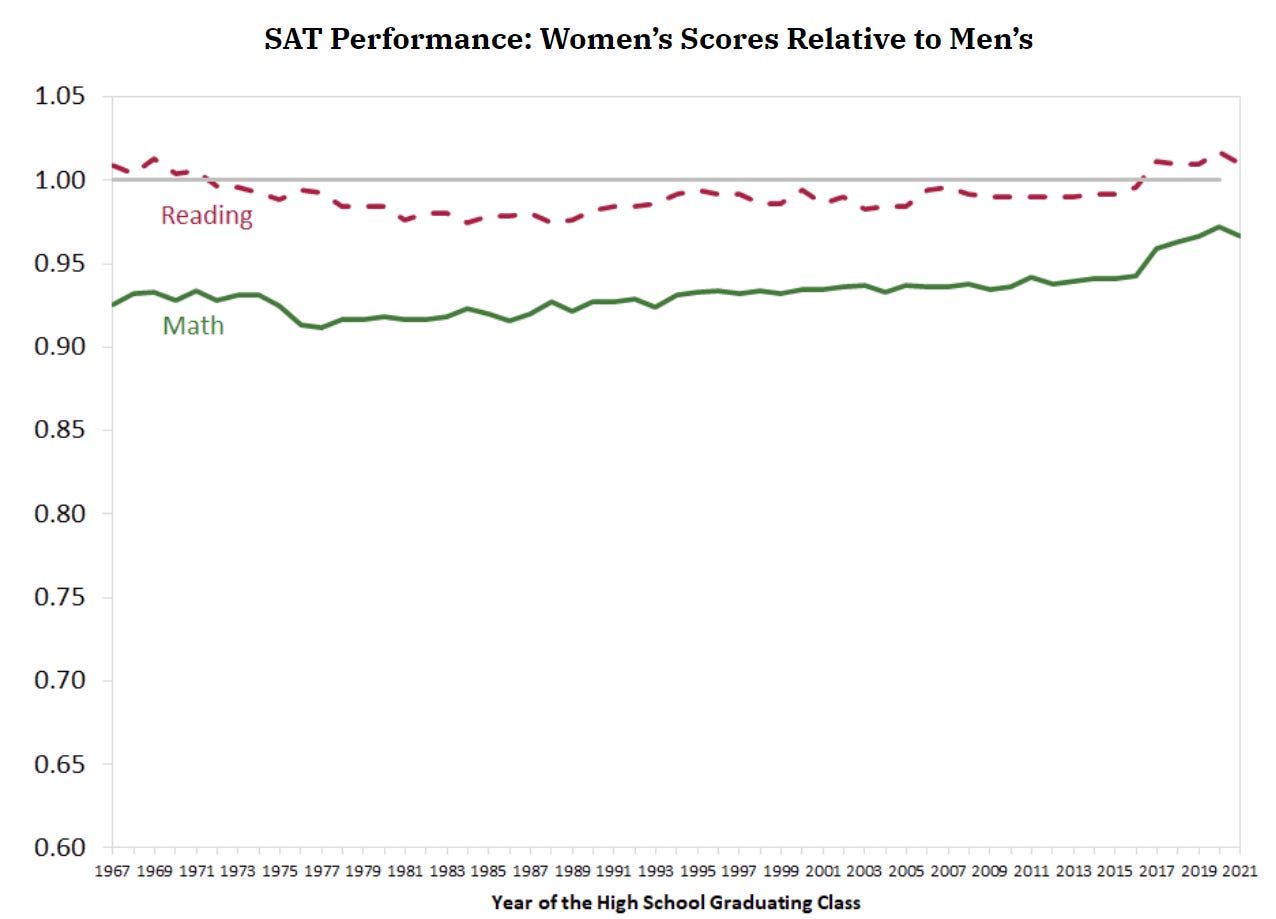

However, it does not appear that there is a systematic trend in the relative performance of boys and girls at the high school level. The next figure shows the relative female-to-male SAT score in reading and math.

There is an objective measure of knowledge and ability, the SAT, where male performance was overall slightly higher. Then in March 2016 they remodeled the test in a way that hurt male relative scores, but they were still slightly higher despite otherwise worse performance in high school.

So what did the colleges do? They mostly stopped using the objective measure. Instead, they now look only at other factors, such whether you can organize your life around checking boxes and forming narratives and maximizing your GPA. Those are all metrics in which the inequality goes the other way and favors girls.

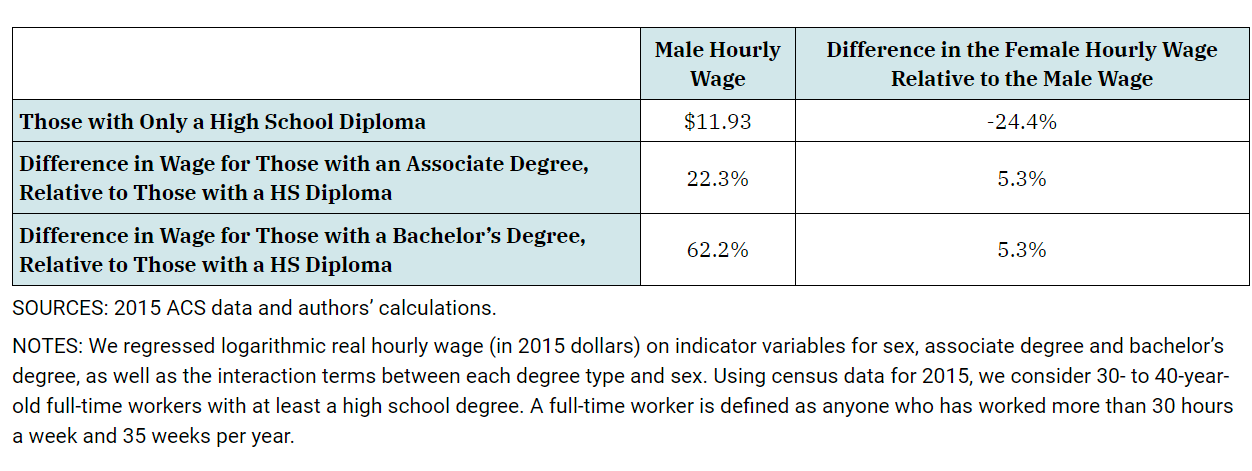

They cite evidence that women enjoy greater returns to college in 2015:

Men go on to college much less, so their college subgroup reflects more selection and should have a bigger non-causal earnings boost, yet women get a 30% larger return. Even if you discount for labor force participation it is still a ~23% edge.

There are several obvious counterarguments.

-

People choosing to go to college do not seem to mostly do so on the basis of realistic estimate of the real rate of return. They certainly do not choose where to go and what to study in a way that maximizes their returns. Mostly the kids choosing are not well informed about their prospects. Flip side is that there is at least some awareness of what the high school graduate job market looks like.

-

Incentives for lifetime earnings have to reflect household income. Men going to college gain the ability to date and marry women who are also college graduates. Women have a strong preference not to ‘date down’ in educational attainment. A man with a college degree has a good chance to land a college graduate, and a man without one is going to have a hard time.

-

Conditional on marriage at all, the chance a man with a degree marries a graduate is something like 75%, whereas without one their chance is more like 20%, and they are less likely to marry at all. So this is a 55% chance to pick up the woman’s income gains from college as well.

-

Whereas for women, the gap (because math) is lower, more like 15% versus 55%, or only a 40% difference. That makes up for a lot purely on income.

-

If you add in other related incentives, and the other incentives men have to be more successful on the dating and marriage markets, one could say that the male incentive for getting a college degree seems clearly in excess of the female one.

-

-

If the math here was fully true and believed (if people in general don’t believe it, it won’t impact decisions), and returns to college for men are a 62% hourly earnings increase, then anyone capable of finishing college would be smart enough to go to college. That is a completely absurd financial return even without considering one’s other prospects.

-

Yes, ~100% is better than 62%, but in a real sense they are the same number, ‘high enough that you should not be asking questions,’ unless you think a huge chunk of that is selection effects and would not be a realized gain. If it’s pure signaling, it’s still worth it individually.

-

I do not think that it is a no brainer to go to college, because I do not think the full 62% or 100% is real due to a lot of it being selection effects and because there are strong other options. But if you think you are looking at 62% higher lifetime earnings for spending four years at a college, plus a giant rise in dating and marriage market value, you should be roaring to go.

-

As many have noted, if you want to help the disadvantaged get better educations, do not focus on elite university admissions policies. Almost all value lies elsewhere.

Richard Ngo: Here’s a paragraph that viscerally highlights how much of a bubble most elite university students + grads are in. It’s crazy that there are so many high schools where even going to the flagship state university is practically unprecedented.

Quoted Text: According to the researchers’ calculations, 45 percent of Texas’s 1,700 public high schools never sent students to UT Austin and Texas A&M, College Station, in the years before the 10 percent program. After the policy change, only 7 of these 775 “never” high schools consistently sent any students to these two flagships. Nearly half never sent a single student to either flagship in the 18 years between 1998 and 2016. The remainder of these “never” schools occasionally had a student or two enroll in a flagship. But these occasional instances didn’t add up to much of a track record.

Richard Ngo: Perhaps the craziest part: the “10 percent program” mentioned guarantees entry to at least 10% of students at every Texas high school. If kids aren’t going because schools didn’t tell them about the program, that feels superlatively incompetent. But what are other explanations?

The other explanation is that the kids from these schools cannot afford to go to UT Austin or Texas A&M, are unwilling or unable to go that far from home, or quite reasonably believe that this automatic admission does not mean they are prepared and they would fail. It makes sense that the majority of admitted students from the bottom half of schools would decline for these reasons.

What this doesn’t explain is 99%+ of them turning the opportunity down. The high schools clearly are not selling this at all. Some additional incentives for the schools are required, if we want the outcome to change. It also would make sense to take the very top of each school, and offer at least the valedictorian a full free ride, which then establishes a link to build upon, someone who can report back.

This points to a clear strategy, if one wants it badly enough, for getting into a pretty good school at a reasonable price. You can move your family to Texas, and live in one of those “never” high school districts that comprise 45% of the state. Yes, your child then still has to place in the top 10% of that school, but this seems not so hard if you take aim at that goal on purpose and the child could handle going to UT Austin or Texas A&M.

You then get in-state tuition of $11.7k at UT Austin or $13k for UT Austin, before any scholarships.

Is moving to a different state and city a big ask? Most definitely. We are asking families and students to upend their lives in order to play this kind of game. It is very reasonable to opt out of that race. But if you do opt in, perhaps play to win it?

Also note that a similar path is available in California, if you do not want to mess with Texas.

Study finds that if you emphasize income sharing agreements (ISAs) then this increases ISA uptake by 43%, and that students are responsive to changes in contract terms when brought to their attention. That is distinct from asking whether ISAs are good or bad.

I have gone back and forth on ISAs over the years.

Right now I am thinking they are a bad idea.

A student considering college is facing a large hold-up problem. Attending college, or the right college, sends a powerful signal, so the colleges can potentially use this positional good to extract a large percentage of the future wealth of the student.

Thus, the student being liquidity constrained, and unable to contract out that future wealth, is protective. If we make it possible and typical to put one’s future income in play this way, then the actual price could go way up, potentially up to the point where one should frequently be indifferent or confused on whether to go to college at all.

Loans of course do the same thing. If students could not take out loans, then the college could only extract the student’s current wealth and that of their family, and force them to do work on the college’s behalf. But loans at least do not give them a share of the fat tailed upside, and are capped by what is repayable in a typical case. An ISA would potentially allow full price discrimination and extraction.

There is also the incentive problem. You do not want to take the best and brightest, and effectively impose an additional income tax. Taxes are dangerously high already.

Bryan Caplan notes that the concept of ‘out of state tuition’ is wild.

In the most recent data, average out-of-state tuition for four-year colleges was $26,382, versus $9,212 for in-state — roughly a 3:1 ratio.

This is a tough break if you’re from Wyoming, which has only one state school, the University of Wyoming. You can either pay $6,612 and go there, or leave the state and pay though the nose.

Do those state schools also favor the wealthy? Kevin Carey of the Atlantic says yes.

Kevin Carey: Remember that study from a couple weeks ago about how Ivy League schools favor the rich in admissions? Many public universities do the same thing.

While there are exceptions, you can mostly predict how sold-out a big public university with a combination of “Is it in a Red state?” and “Does it have a good football team — or *anyfootball team?”

There are also big differences between in-state and out-of-state students. Some flagships are best understood as two universities in parallel — an egalitarian institution for state residents with a side hustle as an expensive private school for the wealthy.

One very notable exception among both public and private colleges: Almost uniformly, engineering schools don’t favor the wealthy. Having real academic standards is a powerful counterbalance to the temptations of money.

Bottom line: It’s a mistake to think that only ultra-rich colleges favor the ultra-rich. The more public universities are starved of resources or just left to their own devices to de facto privatize, the worse this problem will become.

Matthew Yglesias: “If you’re curious about why so many rich kids are on campus, it’s because places like the University of Alabama give an effective 45 percent bump to the children of the top 1 percent.”

This all matches my understanding.

Except that it seems great. Alabama has both Alabama-Instate and Alabama-Outstate.

If you want to attend Alabama-Instate, all you have to do is live in Alabama. You get reasonable tuition, a solid education and the ability to root for the Crimson Tide. The overall acceptance rate is 79%, so for in-state it was even higher. Raising that further on the school’s end would likely not be doing these students any favors, as the marginal student is not going to be prepared for a four-year college.

Meanwhile, those who want to buy a Crimson Tide uniform, or otherwise really like something about Alabama in particular (such as their history of religious tolerance), can pay the full sticker price, and are held to a higher standard, and yes here wealth helps.

But that seems good? If you are an in-state student you want rich kids coming to the university to help pay for everyone else, including via past and future donations, and so you can network with them. Alabama also offers academic scholarships to attract top students from out of state, which again is good for the rest of the students there, they’re not fighting for space. Meanwhile, if you are out of state and not rich, you have your own state school. Almost all of them are similarly solid.

This is also good because of an incentive mismatch in providing public goods. If Alabama were to lower tuition for out-of-state students, or make the university better in other ways, then demand would rise while supply remains fixed, and selectivity would have to rise a lot. This would hurt in-state residents over and above the lost revenue, making them a lot worse off.

Instead, by ensuring that Alabama residents enjoy most of the gains, Alabama has aligned incentives to properly invest in the quality of its university. Good.

Another way to look at this is that these colleges are imposing very high opt-in marginal wealth and income taxes on America, in exchange for those who pay a lot getting small increases in college prestige and moderate increases in ability to select between them, and most rich people feel obligated to pay, while those that don’t want to can opt out. That seems like a great system, if you imposed such tax levels (often essentially 100%) in any other way it would be a complete disaster and they’re not getting that much in return.

The flaw in that plan is that we are also taxing children, while not taxing the childless rich (or middle class), which is a massive distortion we do not want. Ideally we would supplement this with shifting other taxes into a progressive tax on childlessness, or a tax rate deduction for children, to correct the problem.

Alex Tabarrok wonders how all this is constitutional under the Privileges and Immunities Clause (Article IV, section 2). A commentor notes this was unanimously rejected in Martinez v. Bynum, another cites Vlandis v. Kline.

Bryan Caplan: The straightforward explanation for the persistence of the massive price gap is that only in-state students are massively subsidized by their state governments. So instead of picturing out-of-state tuition as a “monopoly price,” we should think of out-of-state tuition as the roughly competitive price.

Which has a shocking implication: Despite much fretting about the exorbitant cost of college, state (and to some extent local) government picks up about two-thirds of the tab.

Alex Tabarrok: My view is that the in-state fee is close to costs (after the obvious subsidies are taken into account) and the out-state fee is well above cost but that it’s not a “monopoly” price per se because the state-schools are not profit-maximizers.

I presume the prices overrepresent the difference, and I do not think one should think of there being a single ‘competitive’ price. This is an oligopoly-style situation, where the college has a lot of pricing power.

If the schools are forced to charge below market for in-state students, that is going to raise the market clearing price for other students in multiple ways. Schools will want to make up the revenue, and also they know that highly price-sensitive students will already be going to their state school, so appealing to the lower end is much less exciting. Also many students get various scholarships and discounts, so this is only the tuition for the truly marginal out of state student, not the average out of state student.

Exactly what is the ‘cost’ depends on how you do the accounting. Schools are providing many services beyond educating undergraduates, and providing those makes the school better for undergraduates but also is important otherwise, so how do you account for such costs?

What about the impact of an Ivy+ education versus what you would expect in a second-tier school? Looking backwards, you get a much better fat tail on the high end, but the default case changes little.

We find that students admitted off the waitlist are about 60 percent more likely to have earnings in the top 1 percent of their age by age 33. They are nearly twice as likely to attend a top 10 graduate school, and they are about 3 times as likely to work in a prestigious firm such as a top research hospital, a world class university, or a highly ranked finance, law or consulting firm. Interestingly, we find only small impacts on mean earnings. This is because students attending good public universities typically do very well. They earn 80th-90th percentile incomes and attend very good but not top graduate schools.

The bottom line is that going to an Ivy-Plus college really matters, especially for high-status positions in society.

This result seems like a strong endorsement of the signaling and networking models of educational advantages at Ivy+ schools. If they provided genuinely superior educations, we would expect to see a very different result. Instead, what we see is a lottery ticket to the elite, because it is exactly in those elite circles that who you know matters and where you need that Ivy+ name to get in the door.

Which, in turn, suggests that it is exactly the legacies and other rich kids that provide the differential value of the Ivy+ degree, as many others have noted.

Should one abandon the top schools at this point?

Nate Silver: Just go to a state school. The premium you’re paying for elite private colleges vs. the better public schools is for social clout and not the quality of the education. And that’s worth a lot less now that people have figured out that elite higher ed is cringe.

Paul Skallas: I’ve literally sat on hiring committees where my boss put ivy league graduates at the top of the pile if they have similar experience

Nate Silver: Right, and I’m suggesting this will decrease because the Ivy Leagues are rapidly losing status. Not to the point where they’ll lack status. But enough that they won’t be as “worth it” to as many people on the margin.

Paul Graham: Social clout and quality of education aren’t the only two factors in the value of a university. There’s another that’s even more important: the quality of the other people there. And like it or not, that will be higher at an elite university.

Nate Silver: I don’t disagree but think that could also have a multiplier effect, e.g. if elite private schools go from attracting a broader cross-section of smart people to a narrower one, the value of social ties and learning through osmosis declines.

Madison: For low-income students like myself, Harvard is cheaper to attend than a state school. For any family that isn’t earning over $150k, your argument is invalid.

Nate Silver then doubled down with a full article making his case.

If the student’s identity were deeply tied up into being a Princeton Man or a Cornell Woman or whatever, then I’d think that was a little weird — but by all means I’d tell them to go, I’m not here to kink-shame.

I’d also tell them to go with the elite private college if (i) they had a high degree of confidence in what they wanted to do with their degree and (ii) it was in a field like law that regards the credential as particularly valuable.

And I’d tell them to strongly consider going if they came from an economically disadvantaged background and had been offered a golden ticket to join the elite. I’m not super familiar with the literature on the selective college wage premium, but it’s among this group of disadvantaged students where the benefits seem to be concentrated.

But if this student was just going to school to “find herself” — and she or her parents were footing most of the bill? Yeah, probably go with the top-flight state school — especially if she’s in a state with a very good in-state public school where the cost savings are much greater.

What is Nate’s evidence?

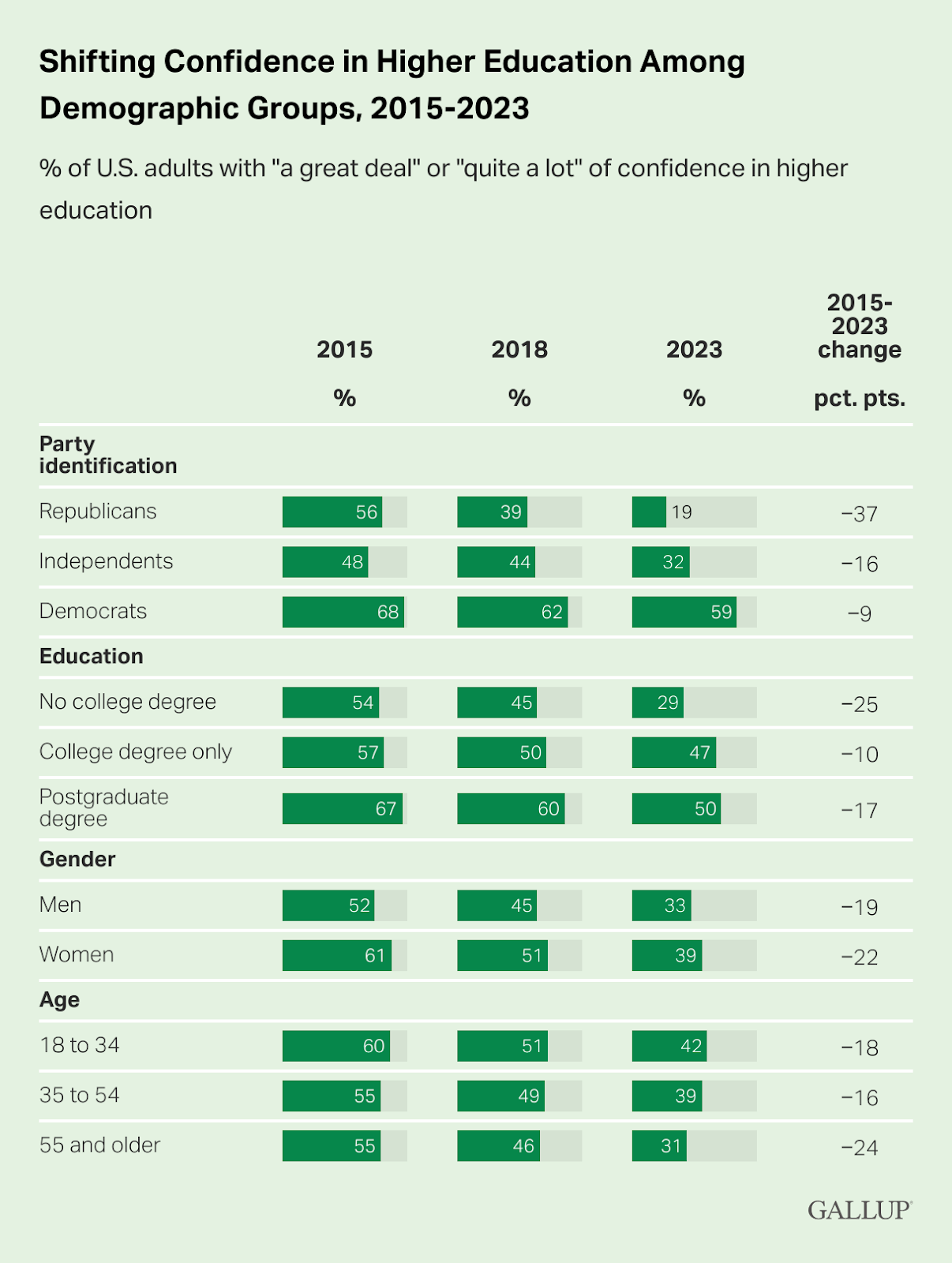

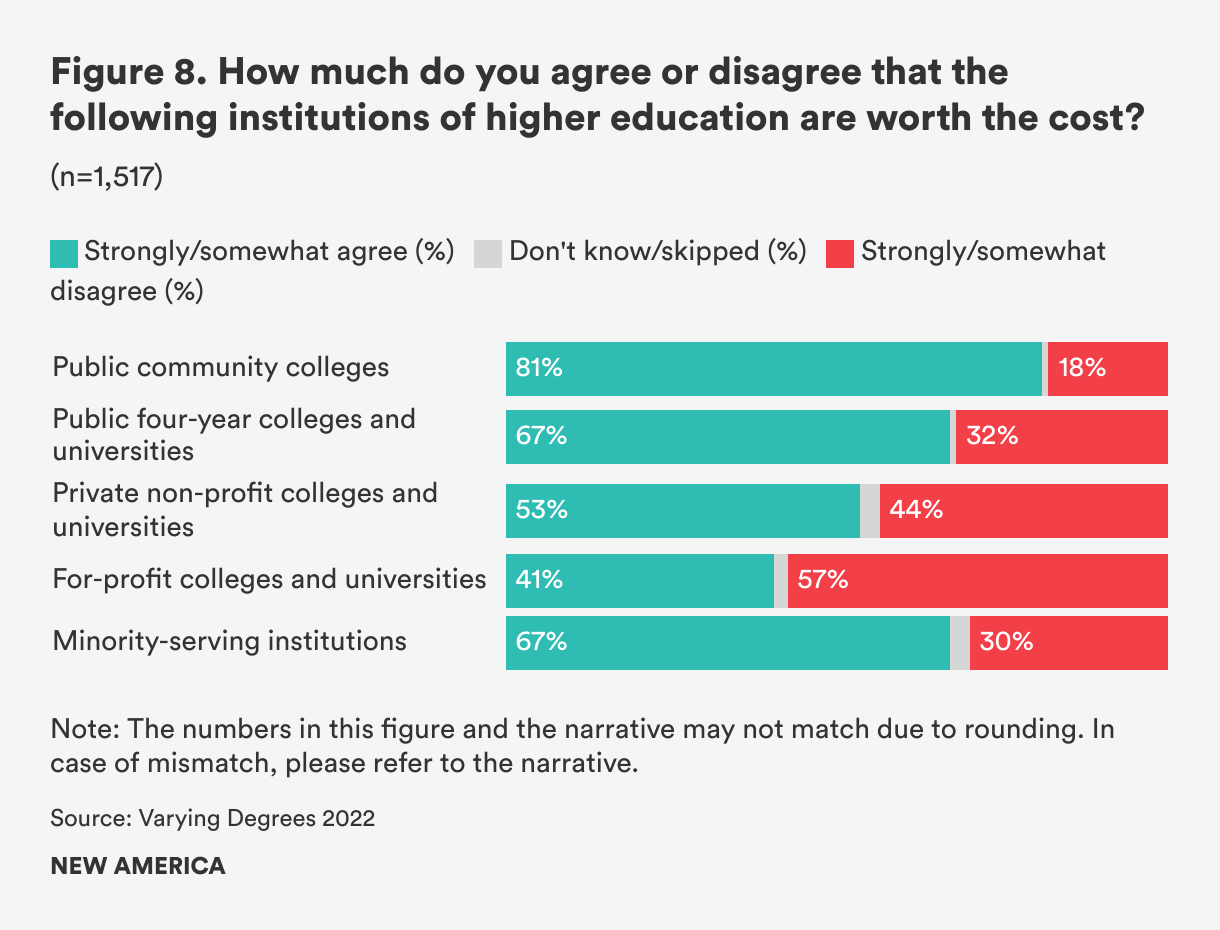

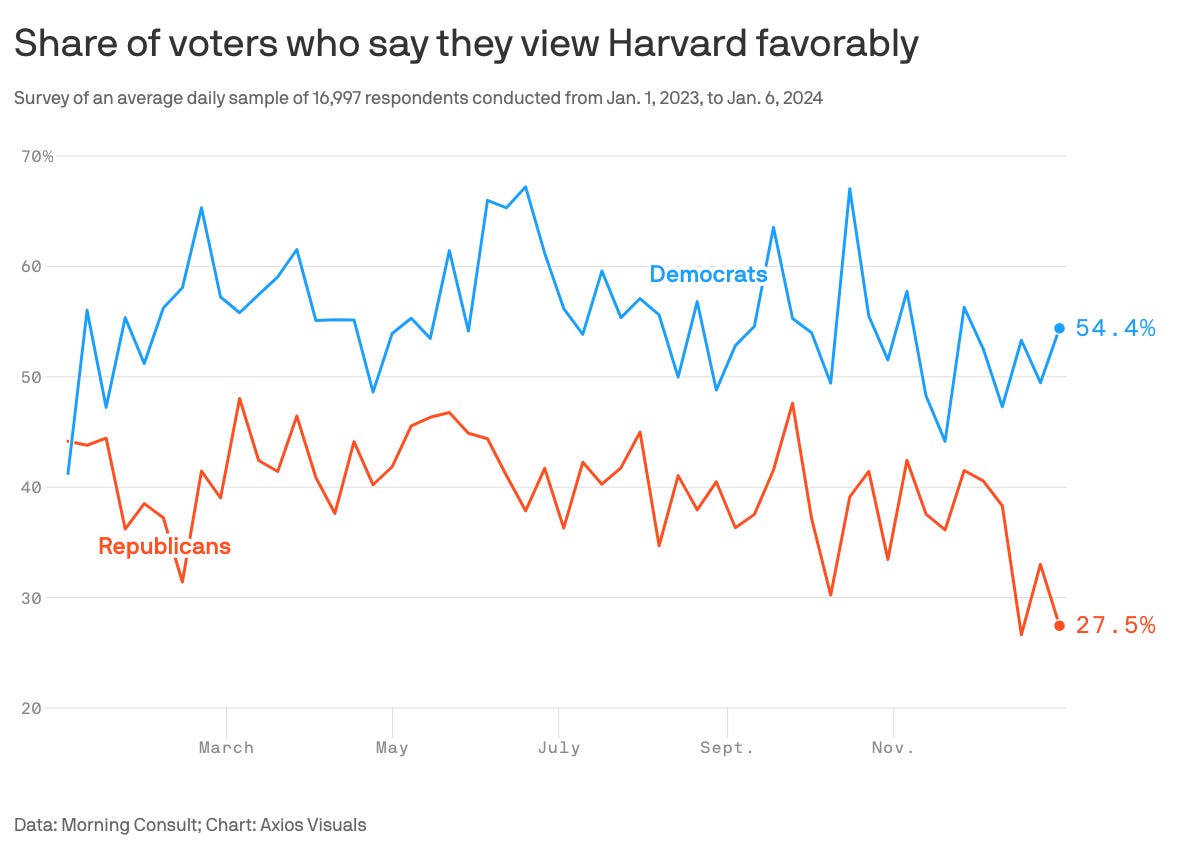

First he points out trust in higher education is declining quite a lot, and people no longer think private college is worth the cost, and everyone hates Harvard.

Hating Harvard is nothing new, that degree has always been very helpful in some places and not taken kindly to in others. There is at least one person who has long said that when asked where you went to college, simply say ‘fyou’ because it would get less hostility than saying Harvard.

Nate recognizes that your degree matters most at the moment of a job application.

mportantly, I expect the decline in perceptions of elite private colleges to extend to people tasked with making hiring decisions. I expect an increasing number of hiring managers to look at two resumes — say, one from a recent graduate of Columbia, and one from a recent graduate of the University of the North Carolina — and potentially see advantages for the UNC student. They’ll regard the Columbia grad as:

More likely to be coddled;

More likely to hold strong political opinions that will distract from their work;

More likely to have benefited from grade inflation and perhaps dubious admissions policies.

Tech and finance aren’t the only professions, obviously. And you could decrease the premium associated with a Harvard or Yale or Columbia degree by 30 percent and it would still be highly valuable. Modern universities serve a lot of different functions and many of them won’t be affected. But I expect the decline in prestige to be enough to have material effects on the value of these degrees, enough they’re no longer “worth it” for some students on the margin.

Some of this has been increasingly going on for a while.

If you are not concerned about such dangers when seeing a recent Ivy graduate, you are not paying attention. No question this degrades the premium. And you will have an adverse selection problem, where those who value your degree are not the places you most want to work.

So the reputation, signaling and status effects are shrinking rapidly. For the true elite, they still remain massive.

The quality of students in terms of business connections and some forms of abstract ‘quality’ will still be higher at the elite schools. This must be balanced against other aspects of your prospective fellow students. Do you want to spend four years with the other students at Columbia, at this point? Have them as my prospective lifelong friends? I sure as hell would not.

Does all this degrade the edges sufficiently to pass the opportunity up?

I do not think we are there yet for the true elite. But only at the very top.

If you get into Harvard or MIT? Well, looks like that is where you are going.

The list of other institutions where you say yes is shrinking.

After the events of April 2024, I cannot say that for Columbia or Yale. No just no.

The bottom also falls away. Pretty much everyone now agrees that the private ‘safety schools,’ the ones that are not near the top, are expensive without giving you much in return.

At that point, yes, your state school is usually the better choice. Indeed, the state schools are plausibly better even at the same price. And the price difference is massive.

To answer a reader request: Never mind top schools versus state schools, say some of the worried. What about those who have short timelines before AGI or ASI? If you believe the world is likely going to at least transform radically and plausibly end soon, is college still worthwhile? If so, does this change other considerations?

The right questions as usual are: What are your alternatives? How much does your decision matter in various future worlds?

There are paths that I consider superior to college, if they are open to you.

If you have the opportunity to go the startup route or real business route in a promising way, I say go for it, including for reasons that have nothing to do with AGI. The same for going into software engineering or other building straight away, if those involved do not care you are young and did not go to college, provided that in your estimation the job is net helpful (or at least non-harmful) to our survival.

If you have the opportunity to do meaningful ‘direct work’ on lowering the probably AI kills us in ways that don’t require the degree, and that would interfere with your ability to attend college, then that seems like a very good justification.

However I would continue to emphasize in general that life must go on. It is important for your mental health and happiness to plan for the future in which the transformational changes do not come to pass, in addition to planning for potential bigger changes. And you should not be so confident that the timeline is short and everything will change so quickly.

The other consideration here is that going to college does not seem like such a high personal cost. You will be going to class eight times a week, and doing a modest amount of additional work, and paying some money. Your time is still largely your own, with lots of opportunities to have fun and explore and do side projects. I started being an essentially full-time professional Magic player well before I was free of college.

So essentially my answer is that this can change the answer if you have a great alternative and it was close, especially if you think you can make a difference quickly. But mostly you should not otherwise alter your plans on this.

The other AI question is, what should we expect to happen to the value of a degree as ordinary mundane AI gets more widespread adaptation, and advances its capabilities? It seems inevitable that this too will hurt the value of a degree, both in earning power and perception and also in terms of actual knowledge. It will be much easier and quicker to learn things on one’s own.

I see this as a similar consideration. It decreases the value proposition, but you still want to hedge your bets, so the discount effect should not be so large. There is a bell curve meme thing going on here.

When the time comes to file applications, it is wise to flood the zone. Putting more marginal effort into the applications themselves seems wise as well, up to a reasonably high point. That is true even if you think there is a good chance you will not want to go to college.

The bigger question is: How much should one structure childhood, yours or your child’s, around maximizing the effectiveness of that application?

One can go all out, as is increasingly common, and as is ubiquitous in East Asia. Consider the entire purpose of childhood to be to ensure admission and to secure one’s future, the rest of it be damned. Do not do zero other things, one must stay sane and learn certain other things, but keep that to an absolute minimum.

I think this is now usually a grave error. The value proposition is too degraded, the fallback options are close enough, there is too little ability to reliably accomplish the mission, the future is far too uncertain especially due to AI. Childhood is too valuable to spend like this.

I can see something approaching this being reasonable in the case where it is vital to maximize aid packages in order to be able to go at all, or especially if one is on the verge of a full free ride at elite institutions. If you have a bunch of various traits that make you highly attractive to top colleges, that increases marginal value a lot.

The better option, I think for most kids, is to strike a balance. You do want to maintain good enough grades and otherwise care on the margin about what your application will look like, so you have better optionality. You still do need to get into the decent state schools, and you want some chance of doing better than that. If you do get into a true elite institution that is great. But unless you have an inside track, do not obsess.

You could also go the whole way and ignore the process entirely, let kids be kids. I have a lot of sympathy for this plan as well. Ultimately we must all talk price. You do want to care a non-zero amount what your transcript looks like and how others will see your story and general record. But yes, focusing on other pursuits and paths seems mostly fine.