New evidence that some supernovae may be a “double detonation”

Type Ia supernovae are critical tools in astronomy, since they all appear to explode with the same intensity, allowing us to use their brightness as a measure of distance. The distance measures they’ve given us have been critical to tracking the expansion of the Universe, which led to the recognition that there’s some sort of dark energy hastening the Universe’s expansion. Yet there are ongoing arguments over exactly how these events are triggered.

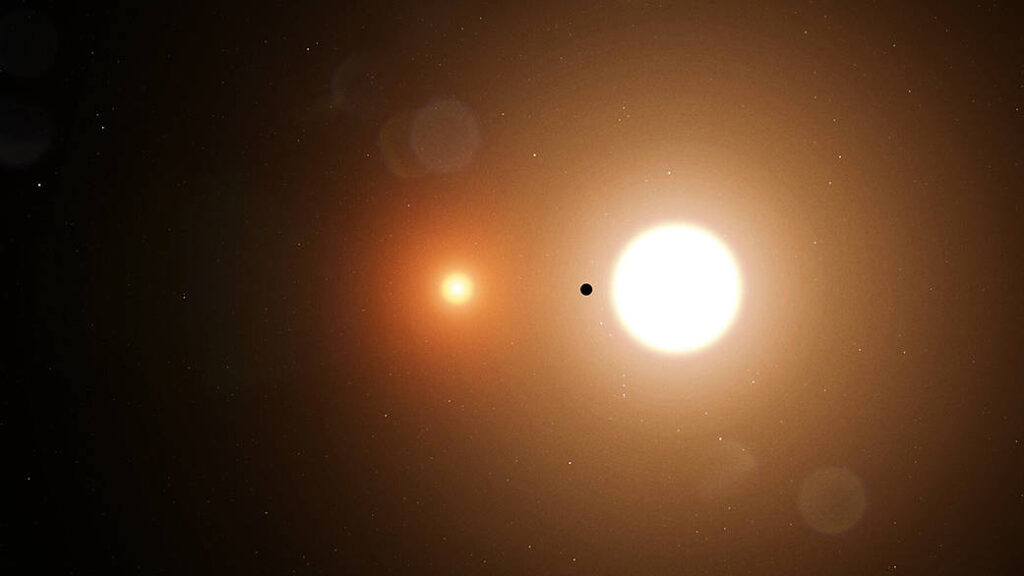

There’s widespread agreement that type Ia supernovae are the explosions of white dwarf stars. Normally, these stars are composed primarily of moderately heavy elements like carbon and oxygen, and lack the mass to trigger additional fusion. But if some additional material is added, the white dwarf can reach a critical mass and reignite a runaway fusion reaction, blowing the star apart. But the source of the additional mass has been somewhat controversial.

But there’s an additional hypothesis that doesn’t require as much mass: a relatively small explosion on a white dwarf’s surface can compress the interior enough to restart fusion in stars that haven’t yet reached a critical mass. Now, observations of the remains of a supernova provide some evidence of the existence of these so-called “double detonation” supernovae.

Deconstructing white dwarfs

White dwarfs are the remains of stars with a similar mass to our Sun. After having gone through periods during which hydrogen and helium were fused, these tend to end up as carbon and oxygen-rich embers: hot due to their history, but incapable of reaching the densities needed to fuse these elements. Left on their own, these stellar remnants will gradually cool.

But many stars are not left on their own; they exist in binary systems with a companion, or even larger systems. These companions can provide the material needed to boost white dwarfs to the masses that can restart fusion. There are two potential pathways for this to happen. Many stars go through periods where they are so large that their gravitational pull is barely enough to hold on to their outer layers. If the white dwarf orbits closely enough, it can pull in material from the other star, boosting its mass until it passes a critical threshold, at which point fusion can restart.

New evidence that some supernovae may be a “double detonation” Read More »