One less thing to worry about in 2025: Yellowstone probably won’t go boom

There’s not enough melted material near the surface to trigger a massive eruption.

It’s difficult to comprehend what 1,000 cubic kilometers of rock would look like. It’s even more difficult to imagine it being violently flung into the air. Yet the Yellowstone volcanic system blasted more than twice that amount of rock into the sky about 2 million years ago, and it has generated a number of massive (if somewhat smaller) eruptions since, and there have been even larger eruptions deeper in the past.

All of which might be enough to keep someone nervously watching the seismometers scattered throughout the area. But a new study suggests that there’s nothing to worry about in the near future: There’s not enough molten material pooled in one place to trigger the sort of violent eruptions that have caused massive disruptions in the past. The study also suggests that the primary focus of activity may be shifting outside of the caldera formed by past eruptions.

Understanding Yellowstone

Yellowstone is fueled by what’s known as a hotspot, where molten material from the Earth’s mantle percolates up through the crust. The rock that comes up through the crust is typically basaltic (a definition based on the ratio of elements in its composition) and can erupt directly. This tends to produce relatively gentle eruptions where lava flows across a broad area, generally like you see in Hawaii and Iceland. But this hot material can also melt rock within the crust, producing a material called rhyolite. This is a much more viscous material that does not flow very readily and, instead, can cause explosive eruptions.

The risks at Yellowstone are rhyolitic eruptions. But it can be difficult to tell the two types of molten material apart, at least while they’re several kilometers below the surface. Various efforts have been made over the years to track the molten material below Yellowstone, but differences in resolution and focus have left many unanswered questions.

Part of the problem is that a lot of this data came from studies of seismic waves traveling through the region. Their travel is influenced by various factors, including the composition of the material they’re traveling through, its temperature, and whether it’s a liquid or solid. In a lot of cases, this leaves several potential solutions consistent with the seismic data—you can potentially see the same behavior from different materials at different temperatures.

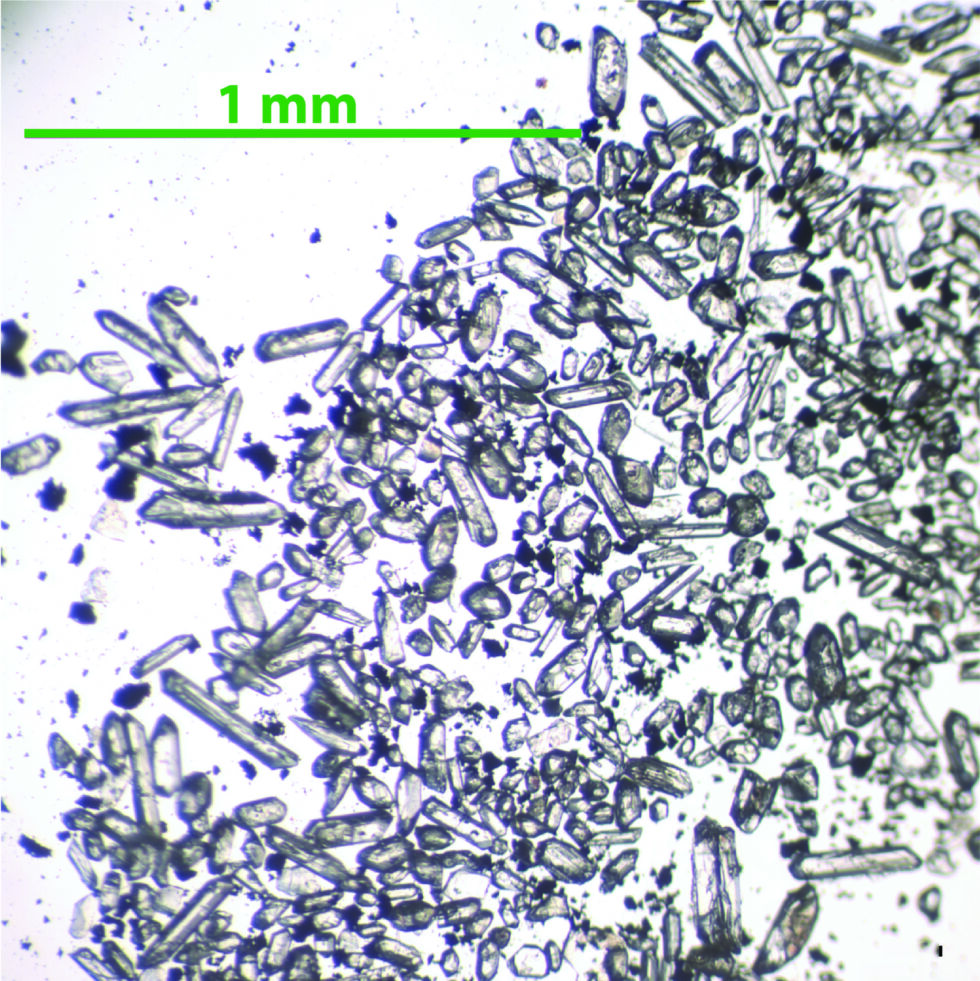

To get around this issue, the new research measured the conductivity of the rock, which can change by as much as three orders of magnitude when transitioning from a solid to a molten phase. The overall conductivity we measure also increases as more of the molten material is connected into a single reservoir rather than being dispersed into individual pockets.

This sort of “magnetotelluric” data has been obtained in the past but at a relatively low resolution. For the new study, a dense array of sensors was placed in the Yellowstone caldera and many surrounding areas to the north and east. (You can compare the previous and new recording sites as black and red triangles on this map.)

Yellowstone’s plumbing

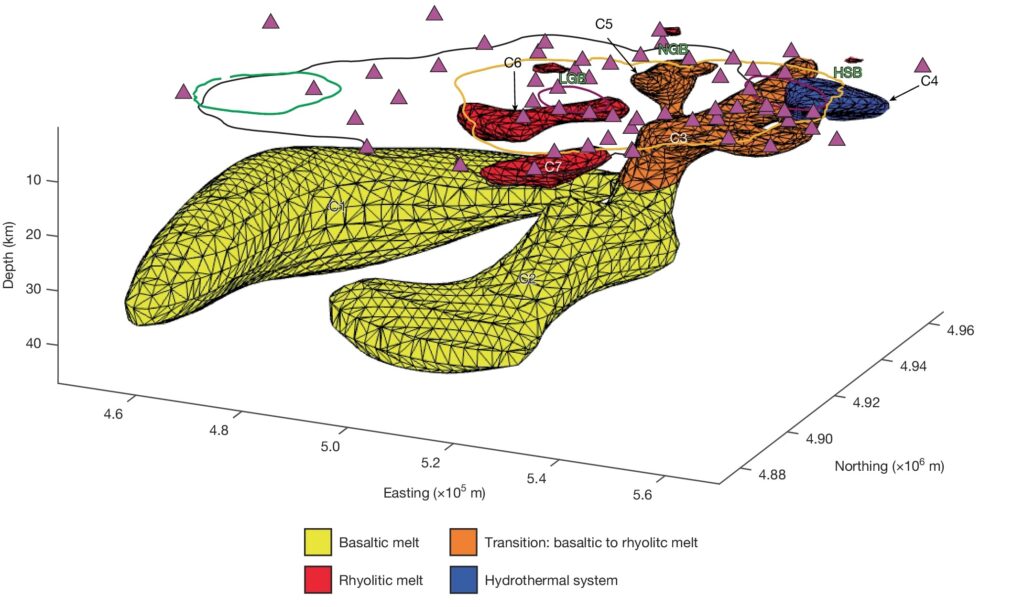

That has allowed the research team to build a three-dimensional map of the molten material underneath Yellowstone and to determine the fraction of the material in a given area that’s molten. The team finds that there are two major sources of molten material that extend up from the mantle-crust boundary at about 50 kilometers below the surface. These extend upward separately but merge about 20 kilometers below the surface.

Underneath Yellowstone: Two large lobs of hot material from the mantle (in yellow) melt rock closer to the surface (orange), creating pools of hot material (red and orange) that power hydrothermal systems and past eruptions, and may be the sites of future activity. Credit: Bennington, et al.

While they collectively contain a lot of molten basaltic material (between 4,000 and 6,500 cubic kilometers of it), it’s not very concentrated. Instead, this is mostly relatively small volumes of molten material traveling through cracks and faults in solid rock. This keeps the concentration of molten material below that needed to enable eruptions.

After the two streams of basaltic material merge, they form a reservoir that includes a significant amount of melted crustal material—meaning rhyolitic. The amount of rhyolitic material here is, at most, under 500 cubic kilometers, so it could fuel a major eruption, albeit a small one by historic Yellowstone standards. But again, the fraction of melted material in this volume of rock is relatively low and not considered likely to enable eruptions.

From there to the surface, there are several distinct features. Relative to the hotspot, the North American plate above is moving to the west, which has historically meant that the site of eruptions has moved from west to east across the continent. Accordingly, there is a pool off to the west of the bulk of near-surface molten material that no longer seems to be connected to the rest of the system. It’s small, at only about 100 cubic kilometers of material, and is too diffused to enable a large eruption.

Future risks?

There’s a similar near-surface blob of molten material that may not currently be connected to the rest of the molten material to the south of that. It’s even smaller, likely less than 50 cubic kilometers of material. But it sits just below a large blob of molten basalt, so it is likely to be receiving a fair amount of heat input. This site seems to have also fueled the most recent large eruption in the caldera. So, while it can’t fuel a large eruption today, it’s not possible to rule the site out for the future.

Two other near-surface areas containing molten material appear to power two of the major sites of hydrothermal activity, the Norris Geyser Basin and Hot Springs Basin. These are on the northern and eastern edges of the caldera, respectively. The one to the east contains a small amount of material that isn’t concentrated enough to trigger eruptions.

But the site to the northeast contains the largest volume of rhyolitic material, with up to nearly 500 cubic kilometers. It’s also one of only two regions with a direct connection to the molten material moving up through the crust. So, while it’s not currently poised to erupt, this appears to be the most likely area to trigger a major eruption in the future.

In summary, while there’s a lot of molten material near the current caldera, all of it is spread too diffusely within the solid rock to enable it to trigger a major eruption. Significant changes will need to take place before we see the site cover much of North America with ash again. Beyond that, the image is consistent with our big-picture view of the Yellowstone hotspot, which has left a trail of eruptions across western North America, driven by the movement of the North American plate.

That movement has now left one pool of molten material on the west of the caldera disconnected from any heat sources, which will likely allow it to cool. Meanwhile, the largest pool of near-surface molten rock is east of the caldera, which may ultimately drive a transition of explosive eruptions outside the present caldera.

Nature, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08286-z (About DOIs).

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

One less thing to worry about in 2025: Yellowstone probably won’t go boom Read More »