40 years later, X Window System is far more relevant than anyone could guess

Widely but improperly known as X-windows —

One astrophysics professor’s memories of writing X11 code in the 1980s.

Getty Images

Often times, when I am researching something about computers or coding that has been around a very long while, I will come across a document on a university website that tells me more about that thing than any Wikipedia page or archive ever could.

It’s usually a PDF, though sometimes a plaintext file, on a .edu subdirectory that starts with a username preceded by a tilde (~) character. This is typically a document that a professor, faced with the same questions semester after semester, has put together to save the most time possible and get back to their work. I recently found such a document inside Princeton University’s astrophysics department: “An Introduction to the X Window System,” written by Robert Lupton.

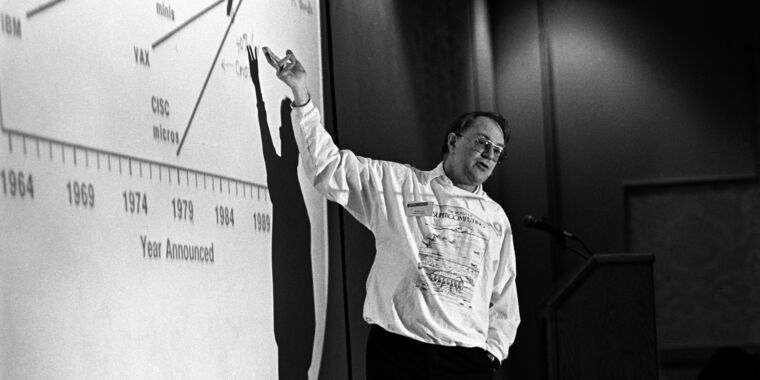

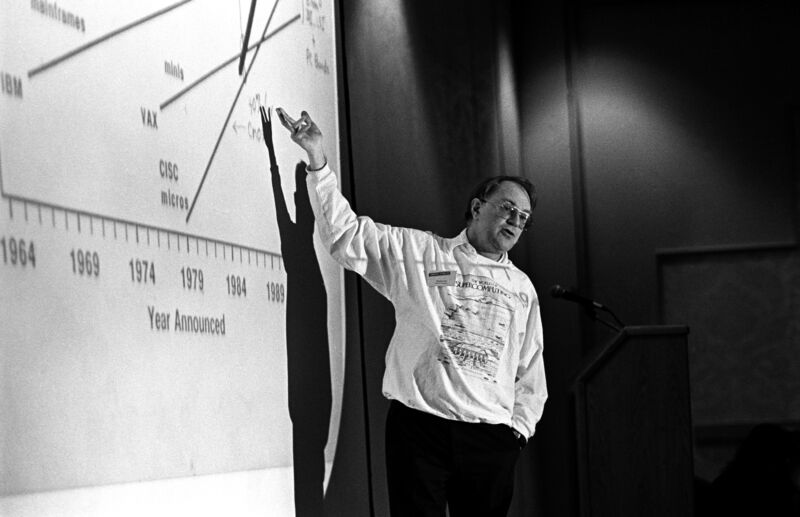

X Window System, which turned 40 years old earlier this week, was something you had to know how to use to work with space-facing instruments back in the early 1980s, when VT100s, VAX-11/750s, and Sun Microsystems boxes would share space at college computer labs. As the member of the AstroPhysical Sciences Department at Princeton who knew the most about computers back then, it fell to Lupton to fix things and take questions.

“I first wrote X10r4 server code, which eventually became X11,” Lupton said in a phone interview. “Anything that needed graphics code, where you’d want a button or some kind of display for something, that was X… People would probably bug me when I was trying to get work done down in the basement, so I probably wrote this for that reason.”

Getty Images

Where X came from (after W)

Robert W. Scheifler and Jim Gettys at MIT spent “the last couple weeks writing a window system for the VS100” back in 1984. As part of Project Athena‘s goals to create campus-wide computing with distributed resources and multiple hardware platforms, X fit the bill, being independent of platforms and vendors and able to call on remote resources. Scheifler “stole a fair amount of code from W,” made its interface asynchronous and thereby much faster, and “called it X” (back when that was still a cool thing to do).

That kind of cross-platform compatibility made X work for Princeton, and thereby Lupton. He notes in his guide that X provides “tools not rules,” which allows for “a very large number of confusing guises.” After explaining the three-part nature of X—the server, the clients, and the window manager—he goes on to provide some tips:

- Modifier keys are key to X; “this sensitivity extends to things like mouse buttons that you might not normally think of as case-sensitive.”

- “To start X, type

xinit; do not type X unless you have defined an alias. X by itself starts the server but no clients, resulting in an empty screen.” - “All programmes running under X are equal, but one, the window manager, is more equal.”

- Using the “

--zaphod” flag prevents a mouse from going into a screen you can’t see; “Someone should be able to explain the etymology to you” (link mine). - “If you say

kill 5 -9 12345you will be sorry as the console will appear hopelessly confused. Return to your other terminal, saykbd mode -a, and make a note not to use -9 without due reason.”

I asked Lupton, whom I caught on the last day before he headed to Chile to help with a very big telescope, how he felt about X, 40 years later. Why had it survived?

“It worked, at least relative to the other options we had,” Lupton said. He noted that Princeton’s systems were not “heavily networked in those days,” such that the network traffic issues some had with X weren’t an issue then. “People weren’t expecting a lot of GUIs, either; they were expecting command lines, maybe a few buttons… it was the most portable version of a window system, running on both a VAX and the Suns at the time… it wasn’t bad.”

40 years later, X Window System is far more relevant than anyone could guess Read More »