In 1995, a Netscape employee wrote a hack in 10 days that now runs the Internet

Thirty years ago today, Netscape Communications and Sun Microsystems issued a joint press release announcing JavaScript, an object scripting language designed for creating interactive web applications. The language emerged from a frantic 10-day sprint at pioneering browser company Netscape, where engineer Brendan Eich hacked together a working internal prototype during May 1995.

While the JavaScript language didn’t ship publicly until that September and didn’t reach a 1.0 release until March 1996, the descendants of Eich’s initial 10-day hack now run on approximately 98.9 percent of all websites with client-side code, making JavaScript the dominant programming language of the web. It’s wildly popular; beyond the browser, JavaScript powers server backends, mobile apps, desktop software, and even some embedded systems. According to several surveys, JavaScript consistently ranks among the most widely used programming languages in the world.

In crafting JavaScript, Netscape wanted a scripting language that could make webpages interactive, something lightweight that would appeal to web designers and non-professional programmers. Eich drew from several influences: The syntax looked like a trendy new programming language called Java to satisfy Netscape management, but its guts borrowed concepts from Scheme, a language Eich admired, and Self, which contributed JavaScript’s prototype-based object model.

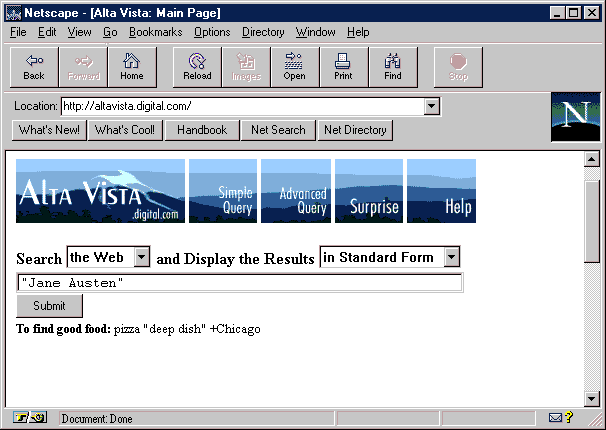

A screenshot of the Netscape Navigator 2.0 interface. Credit: Benj Edwards

The JavaScript partnership secured endorsements from 28 major tech companies, but amusingly, the December 1995 announcement now reads like a tech industry epitaph. The endorsing companies included Digital Equipment Corporation (absorbed by Compaq, then HP), Silicon Graphics (bankrupt), and Netscape itself (bought by AOL, dismantled). Sun Microsystems, co-creator of JavaScript and owner of Java, was acquired by Oracle in 2010. JavaScript outlived them all.

What’s in a name?

The 10-day creation story has become programming folklore, but even with that kernel of truth we mentioned, it tends to oversimplify the timeline. Eich’s sprint produced a working demo, not a finished language, and over the next year, Netscape continued tweaking the design. The rushed development left JavaScript with quirks and inconsistencies that developers still complain about today. So many changes were coming down the pipeline, in fact, that it began to annoy one of the industry’s most prominent figures at the time.

In 1995, a Netscape employee wrote a hack in 10 days that now runs the Internet Read More »