These scientists built their own Stone Age tools to figure out how they were used

hands-on experiments —

Telltale fractures and microscopic wear marks should be applicable to real artifacts.

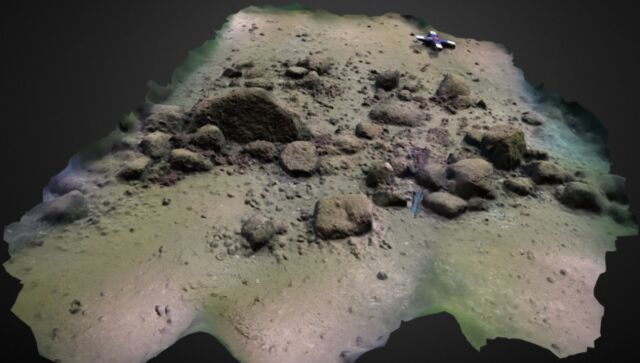

Enlarge / Testing replica Stone Age tools with a bit of wood-scraping.

A. Iwase et al., 2024/Tokyo Metropolitan University

When Japanese scientists wanted to learn more about how ground stone tools dating back to the Early Upper Paleolithic might have been used, they decided to build their own replicas of adzes, axes, and chisels and used those tools to perform tasks that might have been typical for that era. The resulting fractures and wear enabled them to develop new criteria for identifying the likely functions of ancient tools, according to a recent paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. If these kinds of traces were indeed found on genuine Stone Age tools, it would be evidence that humans had been working with wood and honing techniques significantly earlier than previously believed.

The development of tools and techniques for woodworking purposes started out simple, with the manufacture of cruder tools like the spears and throwing sticks common in the early Stone Age. Later artifacts dating back to Mesolithic and Neolithic time periods were more sophisticated, as people learned how to use polished stone tools to make canoes, bows, wells, and to build houses. Researchers typically date the emergence of those stone tools to about 10,000 years ago. However, archaeologists have found lots of stone artifacts with ground edges dating as far back as 60,000 to 30,000 years ago. But it’s unclear how those tools might have been used.

So Akira Iwase of Tokyo Metropolitan University and co-authors made their own replicas of adzes and axes out of three raw materials common to the region between 38,000 and 30,000 years ago: semi-nephrite rocks, hornfels rocks, and tuff rocks. They used a stone hammer and anvil to create various long oval shapes and polished the edges with either a coarse-grained sandstone or a medium-grained tuff. There were three types of replica tools: adze-types, with the working edge oriented perpendicular to the long axis of a bent handle; axe-types, with a working edge parallel to the bent handle’s long axis; and chisel-types, in which a stone tool was placed at the end of a straight handle.

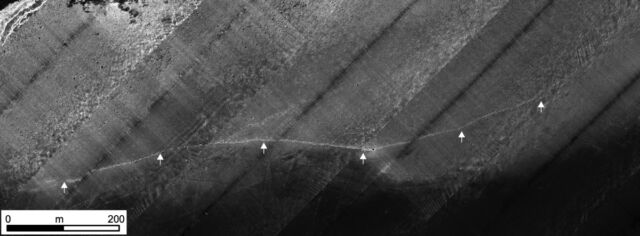

Enlarge / Testing various replicas of Stone Age tools for different uses: A, tree-felling; B, wood-adzing; C, wood-scraping; D, fresh bone-adzing; E, dry hide-scraping; F, disarticulation of a joint.

A. Iwase et al., 2024/Tokyo Metropolitan University

Then it was time to test the replica tools via ten different usage experiments. For instance, the authors used axe-type tools to fell Japanese cedar and maple trees in north central Honshu, as well as a forest near Tokyo Metropolitan University. Axe-type and adze-type tools were used to make a dugout canoe and wooden spears, while adze-type tools and chisel-type tools were used to scrape off the bark of fig and pine. They scraped flesh and grease from fresh and dry hides of deer and boar using adze-type and chisel-type tools. Finally, they used adze-type tools to disarticulate the femur and tibia joints of deer hindlimbs.

The team also conducted several experiments in which the tools were not used to identify accidental fractures not related to any tool-use function. For instance, flakes and blades can break in half during flint knapping; transporting tools in, say, small leather bags can cause microscopic flaking; and trampling on tools left on the ground can also modify the edges. All these scenarios were tested. All the tools used in both use and non-use experiments,ents were then examined for both macroscopic and microscopic traces of fracture or wear.

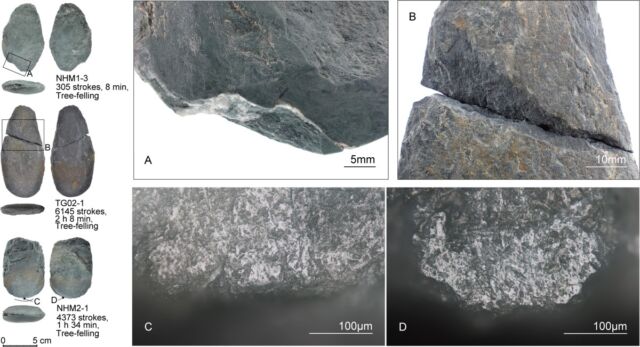

Enlarge / Traces left by tree-felling experiments on replica stone age tools. Characteristic macroscopic (top) and microscopic (bottom) traces might be used to determine how stone edges were used.

Tokyo Metropolitan University

The results: they were able to identify nine different types of macroscopic fractures, several of which were only seen when making percussive motions, particularly in the case of felling trees. There were also telltale microscopic traces resulting from friction between the wood and stone edge. Cutting away at antlers and bones caused a lot of damage to the edges of adze-like tools, creating long and/or wide bending fractures. The tools used for limb disarticulation caused fairly large bending fractures and smaller flaking scars, while only nine out of 21 of the scraping tools showed macroscopic signs of wear, despite hundreds of repeated strokes.

The authors concluded that examining macroscopic fracture patterns alone are insufficient to determine whether a given stone tool had been used percussively. Nor is any resulting micropolish from abrasion an unambiguous indicator on its own, since scraping motions produce a similar micropolish. Combining the two, however, did yield more reliable conclusions about which tools had been used percussively to fell trees, compared to other uses, such as disarticulation of bones.

DOI: Journal of Archaeological Science, 2024. 10.1016/j.jas.2023.105891 (About DOIs).

These scientists built their own Stone Age tools to figure out how they were used Read More »