SpaceX launches mission to bring Starliner astronauts back to Earth

Ch-ch-changes —

SpaceX is bringing back propulsive landings with its Dragon capsule, but only in emergencies.

Stephen Clark – Updated

Enlarge / SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft climbs away from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida, on Saturday atop a Falcon 9 rocket.

NASA/Keegan Barber

NASA astronaut Nick Hague and Russian cosmonaut Aleksandr Gorbunov lifted off Saturday from Florida’s Space Coast aboard a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft, heading for a five-month expedition on the International Space Station.

The two-man crew launched on top of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket at 1: 17 pm EDT (17: 17 UTC), taking an advantage of a break in stormy weather to begin a five-month expedition in space. Nine kerosene-fueled Merlin engines powered the first stage of the flight on a trajectory northeast from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, then the booster detached and returned to landing at Cape Canaveral as the Falcon 9’s upper stage accelerated SpaceX’s Crew Dragon Freedom spacecraft into orbit.

“It was a sweet ride,” Hague said after arriving in space. With a seemingly flawless launch, Hague and Gorbunov are on track to arrive at the space station around 5: 30 pm EDT (2130 UTC) Sunday.

Empty seats

This is SpaceX’s 15th crew mission since 2020, and SpaceX’s 10th astronaut launch for NASA, but Saturday’s launch was unusual in a couple of ways.

“All of our missions have unique challenges and this one, I think, will be memorable for a lot of us,” said Ken Bowersox, NASA’s associate administrator for space operations.

First, only two people rode into orbit on SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft, rather than the usual complement of four astronauts. This mission, known as Crew-9, originally included Hague, Gorbunov, commander Zena Cardman, and NASA astronaut Stephanie Wilson.

But the troubled test flight of Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft threw a wrench into NASA’s plans. The Starliner mission launched in June with NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams. Boeing’s spacecraft reached the space station, but thruster failures and helium leaks plagued the mission, and NASA officials decided last month it was too risky to being the crew back to Earth on Starliner.

NASA selected SpaceX and Boeing for multibillion-dollar commercial crew contracts in 2014, with each company responsible for developing human-rated spaceships to ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station. SpaceX flew astronauts for the first time in 2020, and Boeing reached the same milestone with the test flight that launched in June.

Ultimately, the Starliner spacecraft safely returned to Earth on September 6 with a successful landing in New Mexico. But it left Wilmore and Williams behind on the space station with the lab’s long-term crew of seven astronauts and cosmonauts. The space station crew rigged two temporary seats with foam inside a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft currently docked at the outpost, where the Starliner astronauts would ride home if they needed to evacuate the complex in an emergency.

Enlarge / NASA astronaut Nick Hague and Russian cosmonaut Aleksandr Gorbunov in their SpaceX pressure suits.

NASA/Kim Shiflett

This is a temporary measure to allow the Dragon spacecraft to return to Earth with six people instead of the usual four. NASA officials decided to remove two of the astronauts from the next SpaceX crew mission to free up normal seats for Wilmore and Williams to ride home in February, when Crew-9 was already slated to end its mission.

The decision to fly the Starliner spacecraft back to Earth without its crew had several second order effects on space station operations. Managers at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston had to decide who to bump from the Crew-9 mission, and who to keep on the crew.

Nick Hague and Aleksandr Gorbunov ended up keeping their seats on the Crew-9 flight. Hague originally trained as the pilot on Crew-9, and NASA decided he would take Zena Cardman’s place as commander. Hague, a 49-year-old Space Force colonel, is a veteran of one long-duration mission on the International Space Station, and also experienced a rare in-flight launch abort in 2018 due to a failure of a Russian Soyuz rocket.

NASA announced the original astronaut assignments for the Crew-9 mission in January. Cardman, a 36-year-old geobiologist, would have been the first rookie astronaut without test pilot experience to command a NASA spaceflight. Three-time space shuttle flier Stephanie Wilson, 58, was the other astronaut removed from the Crew-9 mission.

The decision on who to fly on Crew-9 was a “really close call,” said Bowersox, who oversees NASA’s spaceflight operations directorate. “They were thinking very hard about flying Zena, but in this situation, it made sense to have somebody who had at least one flight under their belt.”

Gorbunov, a 34-year-old Russian aerospace engineer making his first flight to space, moved over to take pilot’s seat in the Crew Dragon spacecraft, although he remains officially designated a mission specialist. His remaining presence on the crew was preordained because of an international agreement between NASA and Russia’s space agency that provides seats for Russian cosmonauts on US crew missions and US astronauts on Russian Soyuz flights to the space station.

Bowersox said NASA will reassign Cardman and Wilson to future flights.

Enlarge / NASA astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore, seen in their Boeing flight suits before their launch.

Operational flexibility

This was also the first launch of astronauts from Space Launch Complex-40 (SLC-40) at Cape Canaveral, SpaceX’s busiest launch pad. SpaceX has outfitted the launch pad with the equipment necessary to support launches of human spaceflight missions on the Crew Dragon spacecraft, including a more than 200-foot-tall tower and a crew access arm to allow astronauts to board spaceships on top of Falcon 9 rockets.

SLC-40 was previously based on a “clean pad” architecture, without any structures to service or access Falcon 9 rockets while they were vertical on the pad. SpaceX also installed slide chutes to give astronauts and ground crews an emergency escape route away from the launch pad in an emergency.

SpaceX constructed the crew tower last year and had it ready for the launch of a Dragon cargo mission to the space station in March. Saturday’s launch demonstrated the pad’s ability to support SpaceX astronaut missions, which have previously all departed from Launch Complex-39A (LC-39A) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, a few miles north of SLC-40.

Bringing human spaceflight launch capability online at SLC-40 gives SpaceX and NASA additional flexibility in their scheduling. For example, LC-39A remains the only launch pad configured to support flights of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket. SpaceX is now preparing LC-39A for a Falcon Heavy launch October 10 with NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which only has a window of a few weeks to depart Earth this year and reach its destination at Jupiter in 2030.

With SLC-40 now certified for astronaut launches, SpaceX and NASA teams are able to support the Crew-9 and Europa Clipper missions without worrying about scheduling conflicts. The Florida spaceport now has three launch pads certified for crew flights—two for SpaceX’s Dragon and one for Boeing’s Starliner—and NASA will add a fourth human-rated launch pad with the Artemis II mission to the Moon late next year.

“That’s pretty exciting,” said Pam Melroy, NASA’s deputy administrator. “I think it’s a reflection of where we are in our space program at NASA, but also the capabilities that the United States has developed.”

Earlier this week, Hague and Gorbunov participated in a launch day dress rehearsal, when they had the opportunity to familiarize themselves with SLC-40. The launch pad has the same capabilities as LC-39A, but with a slightly different layout. SpaceX also test-fired the Falcon 9 rocket Tuesday evening, before lowering the rocket horizontal and moving it back into a hangar for safekeeping as the outer bands of Hurricane Helene moved through Central Florida.

Inside the hangar, SpaceX technicians discovered sooty exhaust from the Falcon 9’s engines accumulated on the outside of the Dragon spacecraft during the test-firing. Ground teams wiped the soot off of the craft’s solar arrays and heat shield, then repainted portions of the capsule’s radiators around the edge of Dragon’s trunk section before rolling the vehicle back to the launch pad Friday.

“It’s important that the radiators radiate heat in the proper way to space, so we had to put some some new paint on to get that back to the right emissivity and the right reflectivity and absorptivity of the solar radiation that hit those panels so it will reject the heat properly,” said Bill Gerstenmaier, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability.

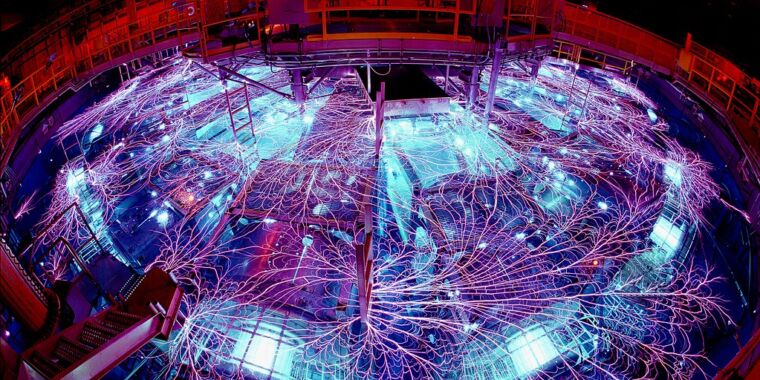

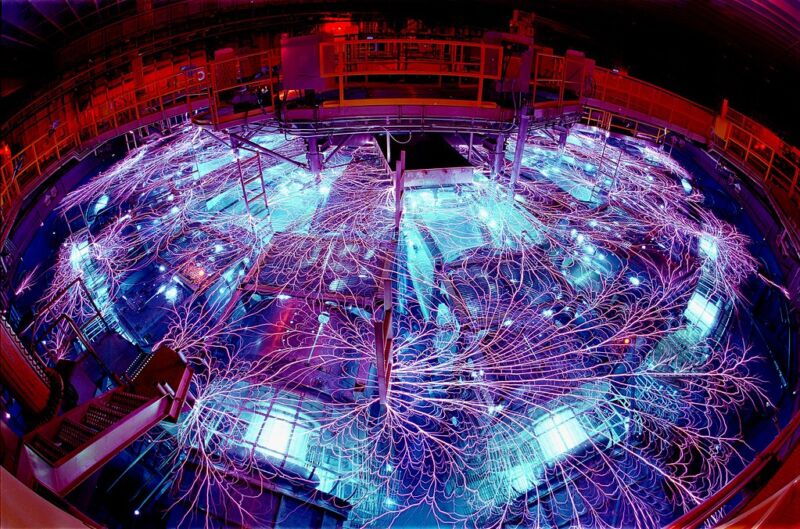

Gerstenmaier also outlined a new backup ability for the Crew Dragon spacecraft to safely splash down even if all of its parachutes fail to deploy on final descent back to Earth. This involves using the capsule’s eight powerful SuperDraco thrusters, normally only used in the unlikely instance of a launch abort, to fire for a few seconds and slow Dragon’s speed for a safe splashdown.

Enlarge / A hover test using SuperDraco thrusters on a prototype Crew Dragon spacecraft in 2015.

SpaceX

“The way it works is, in the case where all the parachutes totally fail, this essentially fires the thrusters at the very end,” Gerstenmaier said. “That essentially gives the crew a chance to land safely, and essentially escape the vehicle. So it’s not used in any partial conditions. We can land with one chute out. We can land with other failures in the chute system. But this is only in the case where all four parachutes just do not operate.”

When SpaceX first designed the Crew Dragon spacecraft more than a decade ago, the company wanted to use the SuperDraco thrusters to enable the capsule to perform propulsive helicopter-like landings. Eventually, SpaceX and NASA agreed to change to a more conventional parachute-assisted splashdown.

The SuperDracos remained on the Crew Dragon spacecraft to push the capsule away from its Falcon 9 rocket during a catastrophic launch failure. The eight high-thrust engines burn hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants that combust when making contact with one another.

The backup option has been activated for some previous commercial Crew Dragon missions, but not for a NASA flight, according to Gerstenmaier. The capability “provides a tolerable landing for the crew,” he added. “So it’s a true deep, deep contingency. I think our philosophy is, rather than have a system that you don’t use, even though it’s not maybe fully certified, it gives the crew a chance to escape a really, really bad situation.”

Steve Stich, NASA’s commercial crew program manager, said the emergency propulsive landing capability will be enabled for the return of the Crew-8 mission, which has been at the space station since March. With the arrival of Hague and Gorbunov on Crew-9—and the extension of Wilmore and Williams’ mission—the Crew-8 mission is slated to depart the space station and splash down in early October.

This story was updated after confirmation of a successful launch.

SpaceX launches mission to bring Starliner astronauts back to Earth Read More »