SpaceX has plans to launch Falcon Heavy from California—if anyone wants it to

There’s more to the changes at Vandenberg than launching additional rockets. The authorization gives SpaceX the green light to redevelop Space Launch Complex 6 (SLC-6) to support Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy missions. SpaceX plans to demolish unneeded structures at SLC-6 (pronounced “Slick 6”) and construct two new landing pads for Falcon boosters on a bluff overlooking the Pacific just south of the pad.

SpaceX currently operates from a single pad at Vandenberg—Space Launch Complex 4-East (SLC-4E)—a few miles north of the SLC-6 location. The SLC-4E location is not configured to launch the Falcon Heavy, an uprated rocket with three Falcon 9 boosters bolted together.

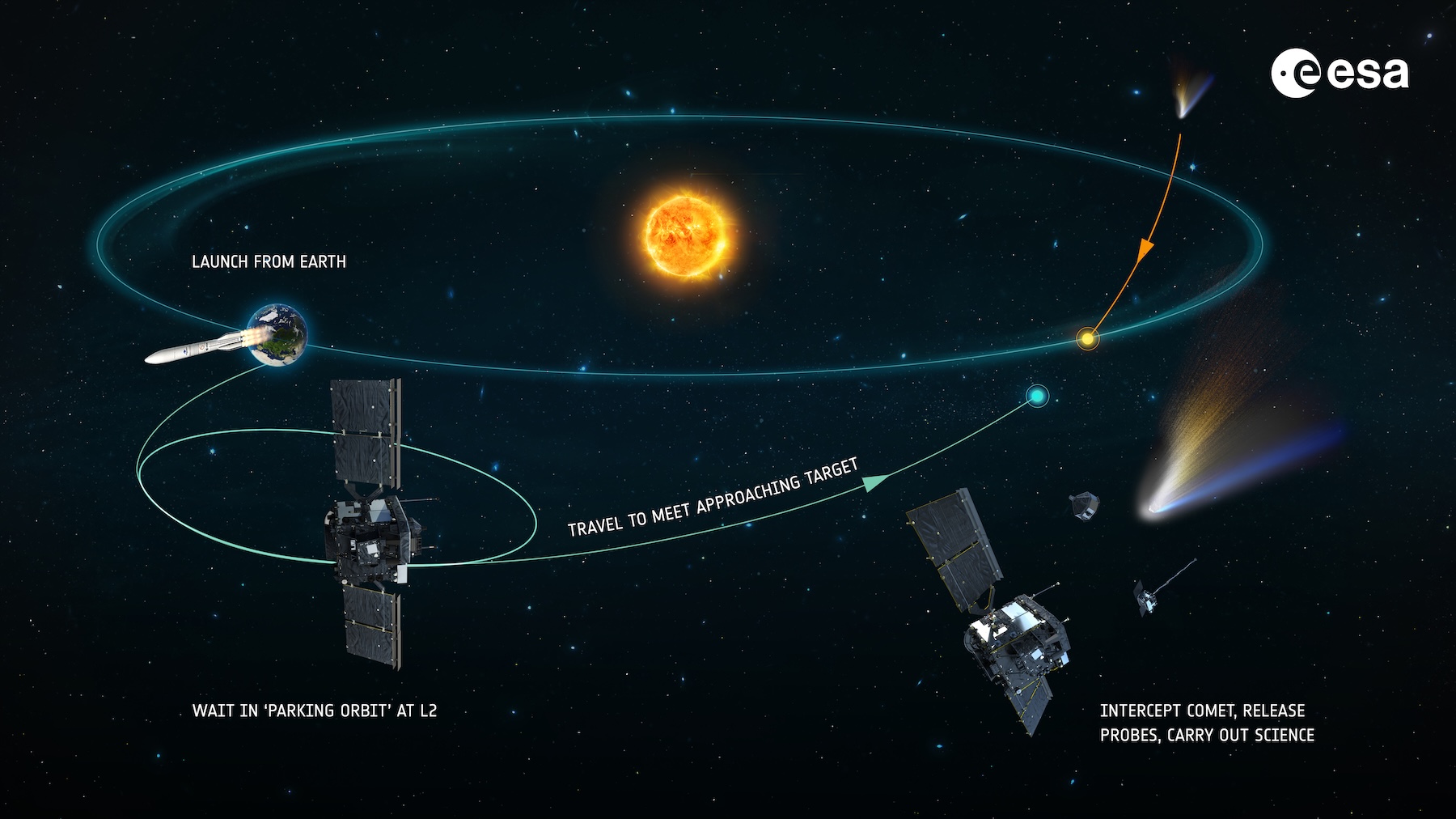

SLC-6, cocooned by hills on three sides and flanked by the ocean to the west, is no stranger to big rockets. It was first developed for the Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory program in the 1960s, when the military wanted to put a mini-space station into orbit for astronauts to spy on the Soviet Union. Crews readied the complex to launch military astronauts on top of Titan rockets, but the Pentagon canceled the program in 1969 before anything actually launched from SLC-6.

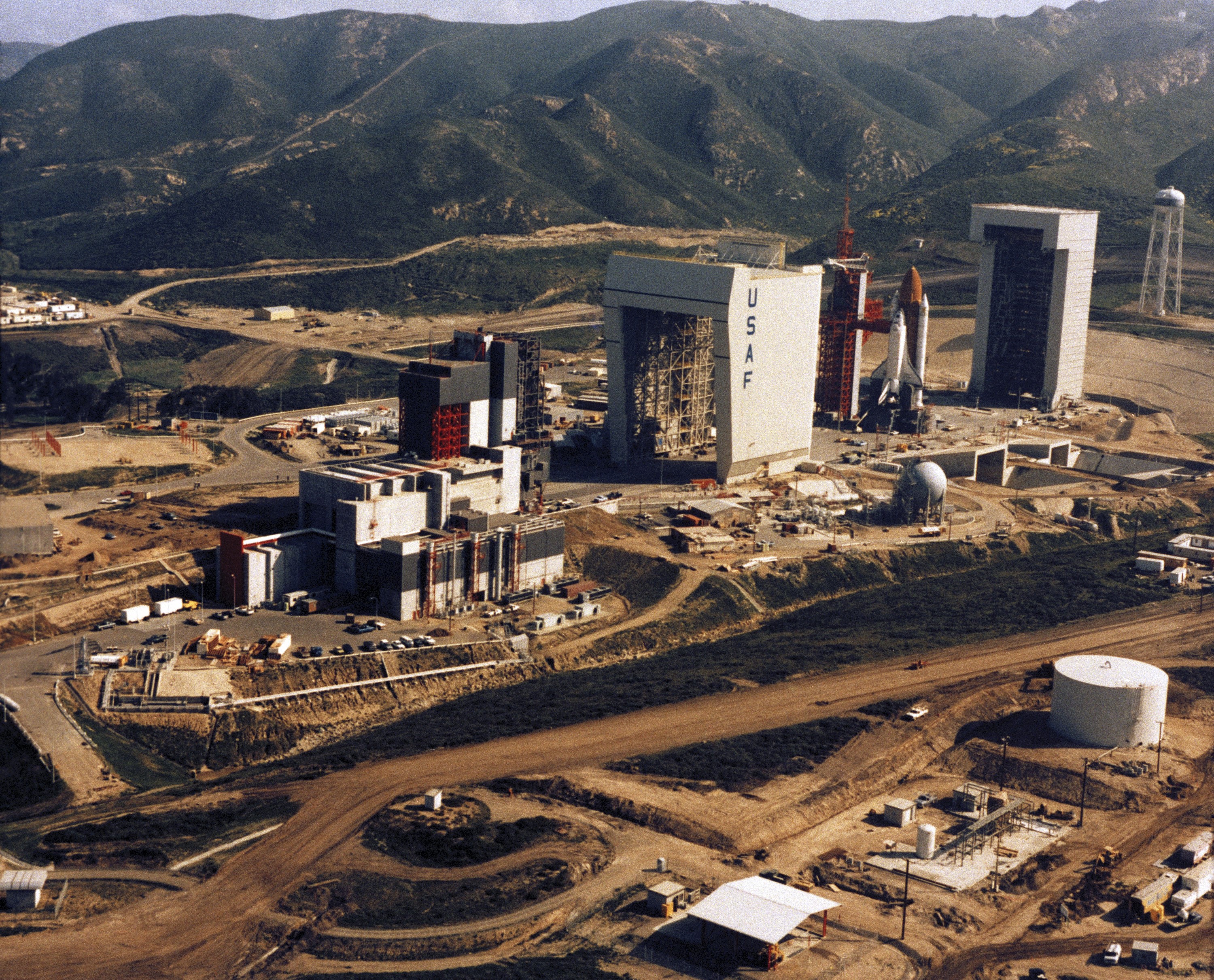

NASA and the Air Force then modified SLC-6 to launch space shuttles. The space shuttle Enterprise was stacked vertically at SLC-6 for fit checks in 1985, but the Air Force abandoned the Vandenberg-based shuttle program after the Challenger accident in 1986. The launch facility sat mostly dormant for nearly two decades until Boeing, and then United Launch Alliance, took over SLC-6 and began launching Delta IV rockets there in 2006.

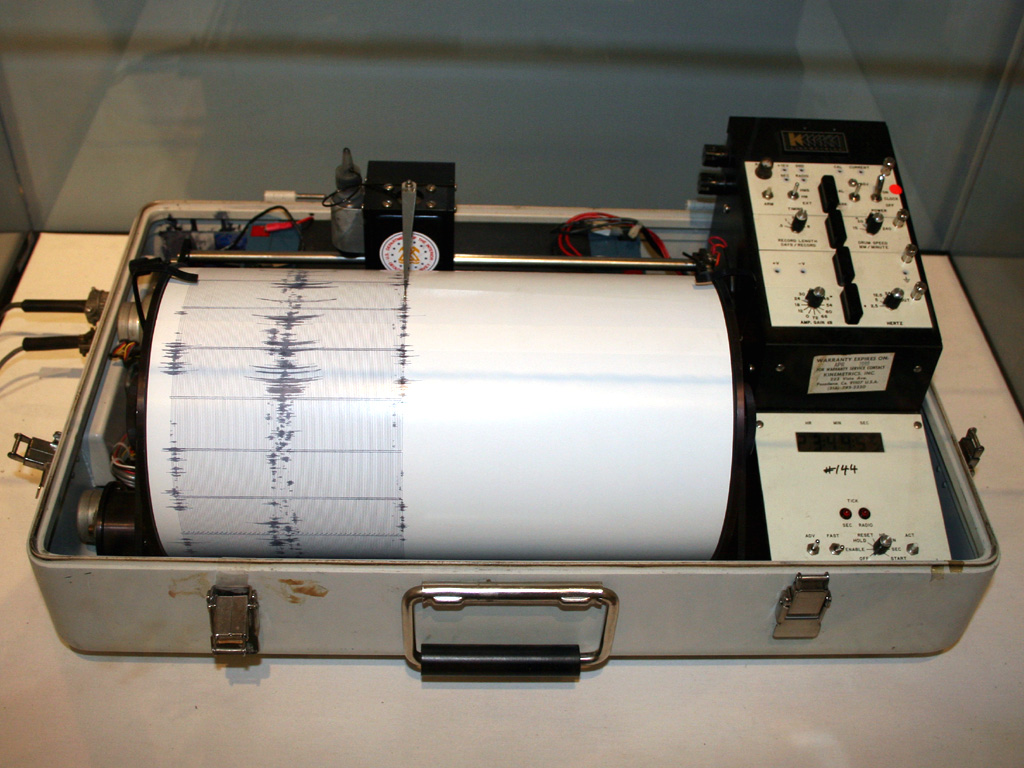

The space shuttle Enterprise stands vertically at Space Launch Complex-6 at Vandenberg. NASA used the shuttle for fit checks at the pad, but it never launched from California. Credit: NASA

ULA launched its last Delta IV Heavy rocket from California in 2022, leaving the future of SLC-6 in question. ULA’s new rocket, the Vulcan, will launch from a different pad at Vandenberg. Space Force officials selected SpaceX in 2023 to take over the pad and prepare it to launch the Falcon Heavy, which has the lift capacity to carry the military’s most massive satellites into orbit.

No big rush

Progress at SLC-6 has been slow. It took nearly a year to prepare the Environmental Impact Statement. In reality, there’s no big rush to bring SLC-6 online. SpaceX has no Falcon Heavy missions from Vandenberg in its contract backlog, but the company is part of the Pentagon’s stable of launch providers. To qualify as a member of the club, SpaceX must have the capability to launch the Space Force’s heaviest missions from the military’s spaceports at Vandenberg and Cape Canaveral, Florida.

SpaceX has plans to launch Falcon Heavy from California—if anyone wants it to Read More »