Tiny, 45 base long RNA can make copies of itself

Self-copying RNAs may have been a key stop along the pathway to life.

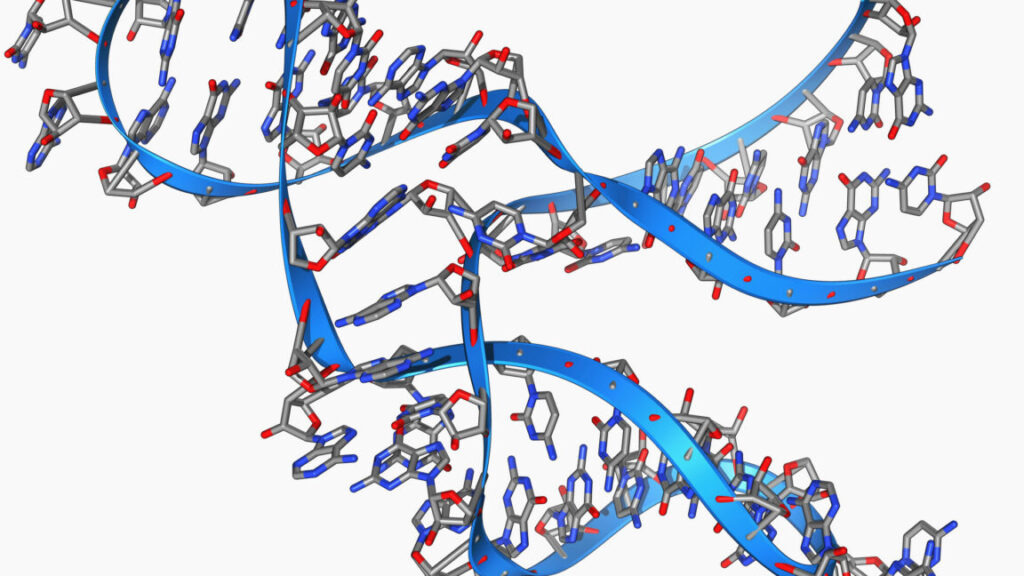

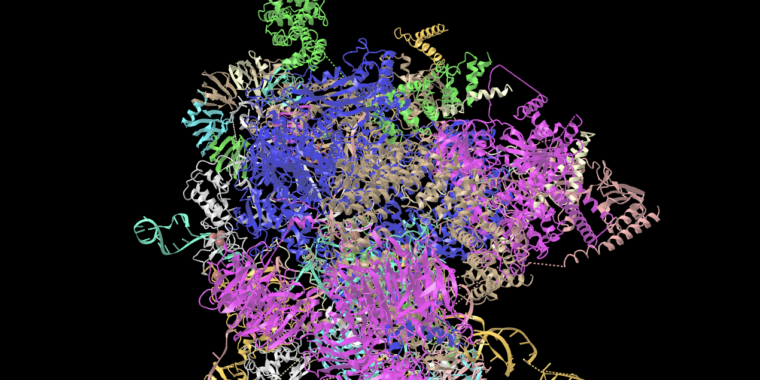

By base pairing with themselves, RNAs can form complex structures with enzymatic activity. Credit: Laguna Design

There are plenty of unanswered questions about the origin of life on Earth. But the research community has largely reached consensus that one of the key steps was the emergence of an RNA molecule that could replicate itself. RNA, like its more famous relative DNA, can carry genetic information. But it can also fold up into three-dimensional structures that act as catalysts. These two features have led to the suggestion that early life was protein-free, with RNA handling both heredity and catalyzing a simple metabolism.

For this to work, one of the reactions that the early RNAs would need to catalyze is the copying of RNA molecules, without which any sort of heritability would be impossible. While we’ve found a number of catalytic RNAs that can copy other molecules, none have been able to perform a key reaction: making a copy of themselves. Now, however, a team has found an incredibly short piece of RNA—just 45 bases long—that can make a copy of itself.

Finding an RNA polymerase

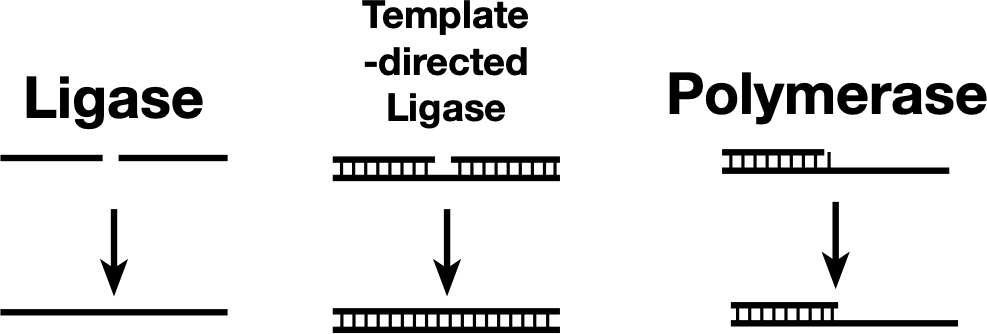

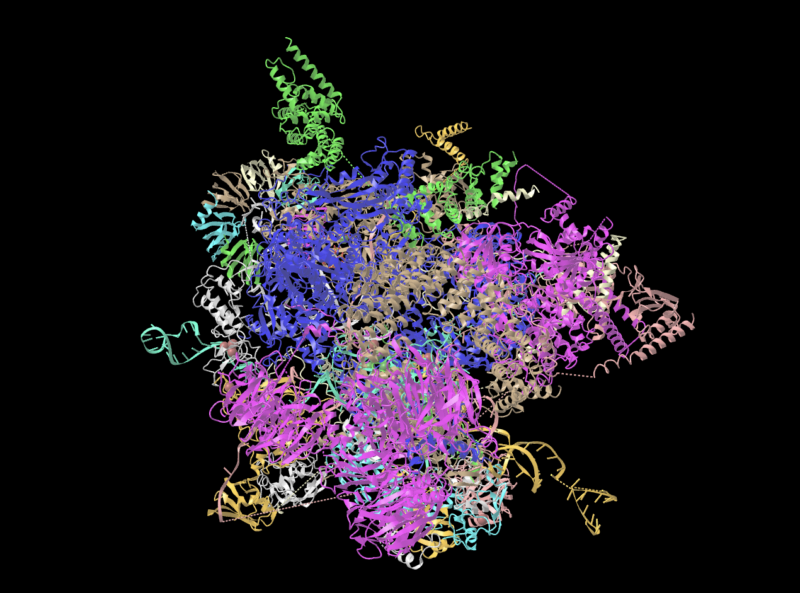

We have identified a large number of catalytic RNAs (generically called ribozymes, for RNA-based enzymes), and some of them can catalyze reactions involving other RNAs. A handful of these are ligases, which link together two RNA molecules. In some cases, they need these molecules to be held together by a third RNA molecule that base pairs with both of them. We’ve only identified a few that can act as polymerases, which add RNA bases to a growing molecule, one at a time, with each new addition base pairing with a template molecule.

Some ligases can link two nucleic acid strands (left), while others can link the strands only if they’re held together by base pairing with a template (center). A polymerase can be thought of as a template-dependent ligase that adds one base at a time. The newly discovered ribozyme sits somewhere between a template-directed ligase and a polymerase.

Credit: John Timmer

Some ligases can link two nucleic acid strands (left), while others can link the strands only if they’re held together by base pairing with a template (center). A polymerase can be thought of as a template-dependent ligase that adds one base at a time. The newly discovered ribozyme sits somewhere between a template-directed ligase and a polymerase. Credit: John Timmer

Obviously, there is some functional overlap between them, as you can think of a polymerase as ligating on one base at a time. And in fact, at the ribozyme level, there’s some real-world overlap, as some ribozymes that were first identified as ligases were converted into polymerases by selecting for this new function.

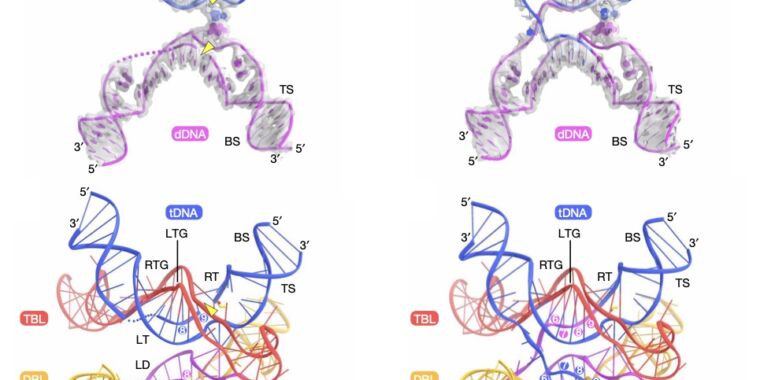

While this is fascinating, there are a few problems with these known examples of polymerase ribozymes. One is that they’re long. So long, in fact, that they’re beyond the length of the sort of molecules that we’ve observed forming spontaneously from a mix of individual RNA bases. This length also means they’re largely incapable of making copies of themselves—the reactions are slow and inefficient enough that they simply stop before copying the entire molecule.

Another factor related to their length is that they tend to form very complex structures, with many different areas of the molecule base-paired to one another. That leaves very little of the molecule in a single-stranded form, which is needed to make a copy.

Based on past successes, a French-UK team decided to start a search for a polymerase by looking for a ligase. And they limited that search in an important way: They only tested short molecules. They started with pools of RNA molecules, each with a different random sequence, ranging from 40 to 80 bases. Overall, they estimated that they made a population of 1013 molecules out of the total possible population of 1024 sequences of this type.

These random molecules were fed a collection of three-base-long RNAs, each linked to a chemical tag. The idea was that if a molecule is capable of ligating one of these short RNA fragments to itself, it could be pulled out using the tag. The mixtures were then placed in a salty mixture of water and ice, as this can promote reactions involving RNAs.

After 11 rounds of reactions and tag-based purification, the researchers ended up with three different RNA molecules that could each ligate three-base-long RNAs to existing molecules. Each of these molecules was subjected to mutagenesis and further rounds of selection. This ultimately left the researchers with a single, 51-base-long molecule that could add clusters of three bases to a growing RNA strand, depending on their ability to base-pair with an RNA template. They called this “polymerase QT-51,” with QT standing for “quite tiny.” They later found that they could shorten this to QT-45 without losing significant enzyme activity.

Checking its function

The basic characterization of QT-45 showed that it has some very impressive properties for a molecule that, by nucleic acid standards, is indeed quite tiny. While it was selected for linking collections of molecules that were three bases long, it could also link longer RNAs, work on shorter two-base molecules, or even add a single base at a time, though this was less efficient. While it worked slowly, the molecule’s active half-life was well over 100 days, so it had plenty of time to get things done before it degraded.

It also didn’t need to interact with any specific RNA sequences to work, suggesting it had a general affinity for RNA molecules. As a result, it wasn’t especially picky about the sequences it could copy.

As you might expect from such a small molecule, QT-45 didn’t tolerate changes to its own sequence very well—nearly the entire molecule was important in one way or another. Tests that involved changing every single individual base one at a time showed that almost all the changes reduced the ribozyme’s activity. There were, however, a handful of changes that improved things, suggesting that further selection could potentially yield additional improvements. And the impact of mutations near the center of the sequence was far more severe, suggesting that region is critical for QT-45’s enzymatic activity.

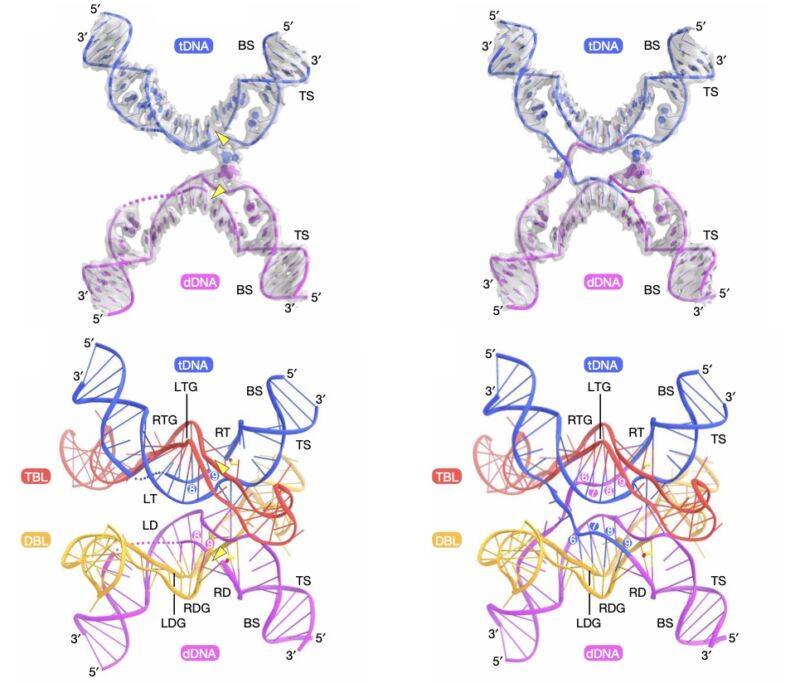

The team then started testing its ability to synthesize copies of other RNA molecules when given a mixture of all possible three-base sequences. One of the tests included a large stretch in which one end of the sequence base-paired with the other. To copy that, those base pairs need to somehow be pried apart. But QT-45 was able to make a copy, meaning it synthesized a strand that was able to base pair with the original.

It was also able to make a copy of a template strand that would base pair with a small ribozyme. That copying produced an active ribozyme.

But the key finding was that it could synthesize a sequence that base-pairs with itself, and then synthesize itself by copying that sequence. This was horribly inefficient and took months, but it happened.

Throughout these experiments, the fidelity averaged about 95 percent, meaning that, in copying itself, it would make an average of two to three errors. While this means a fair number of its copies wouldn’t be functional, it also means the raw materials for an evolutionary selection for improved function—random mutations—would be present.

What this means

It’s worth taking a moment to consider the use of three-base RNA fragments by this enzyme. On the surface, this may seem a bit like cheating, since current RNA polymerases add sequence one base at a time. But in reality, any chemical environment that could spontaneously assemble an RNA molecule 45 bases long will produce many fragments shorter than that. So in many ways, this might be a more realistic model of the conditions in which life emerged.

The authors note that these shorter fragments may be essential for QT-45’s activity. The short ribozyme probably doesn’t have the ability to enzymatically pry base-paired strands of RNA apart to copy them. But in a mixture of lots of small fragments, there’s likely to be an equilibrium, with some base-paired sequences spontaneously popping open and temporarily base pairing with a shorter fragment. Working with these base-paired fragments is probably essential to the ribozyme’s overall activity.

Right now, QT-45 isn’t an impressive enzyme. But the researchers point out that it has only been through 18 rounds of selection, which isn’t much. The most efficient ribozyme polymerases we have at present have been worked on by multiple labs for years. I expect QT-45 to receive similar attention and improve significantly over time.

Also notable is that the team came up with three different ligases in a test of just a small subset of the possible total RNA population of this size. If that frequency holds, there are on the order of 1011 ligating ribozymes among the sequences of this size. Which raises the possibility that we could find far more if we do an exhaustive search. That suggests the first self-copying RNA might not be as improbable as it seems at first.

Science, 2026. DOI: 10.1126/science.adt2760 (About DOIs).

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

Tiny, 45 base long RNA can make copies of itself Read More »