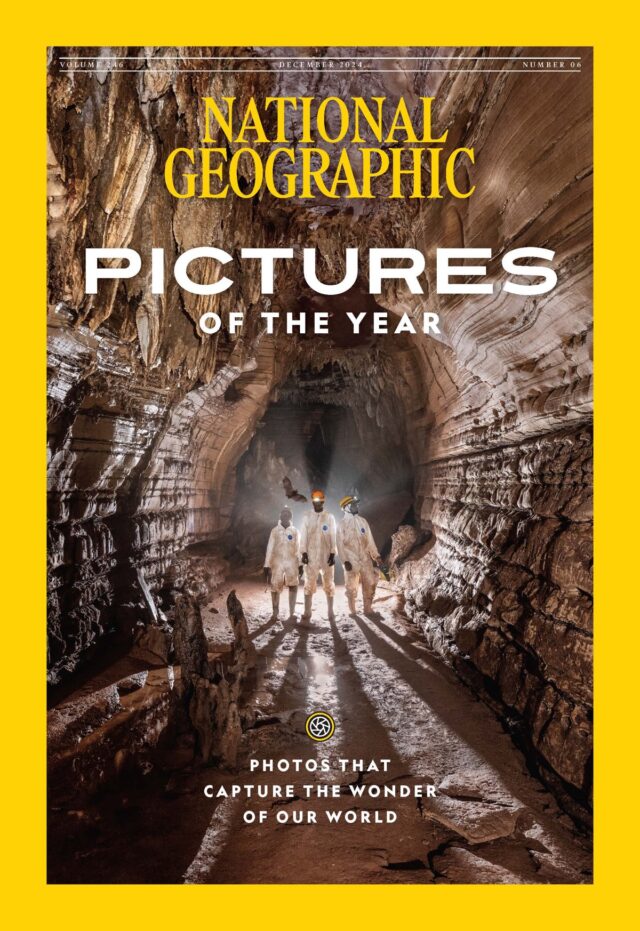

A peek inside the restoration of the iconic Notre Dame cathedral

Tomas van Houtyryve’s striking photographs for National Geographic capture the restoration process.

Notre Dame’s nave is clean and bright thanks to a latex application that peeled away soot and lead. Credit: Tomas van Houtryve for National Geographic

On April 15, 2019, the world watched in transfixed horror as a fire ravaged the famed Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, collapsing the spire and melting the lead roof. After years of painstaking restoration costing around $740 million, the cathedral reopens to the public this weekend. The December issue of National Geographic features an exclusive look inside the restored cathedral, accompanied by striking photographs by Paris-based photographer and visual artist Tomas van Houtryve.

For several hours, it seemed as if the flames would utterly destroy the 800-year-old cathedral. But after a long night of work by more than 400 Paris firefighters, the fire finally began to cool and attention began to shift to what could be salvaged and rebuilt. French President Emmanuel Macron vowed to restore Notre Dame to its former glory and set a five-year deadline. The COVID-19 pandemic caused some delays, but France nearly met that deadline regardless.

Those reconstruction efforts were helped by the fact that, a few years before the fire, scientist Andrew Tallon had used laser scanning to create precisely detailed maps of the interior and exterior of the cathedral—an invaluable aid as Paris rebuilds this landmark structure. French acousticians had also made detailed measurements of Notre Dame’s “soundscape” that were instrumental in helping architects factor acoustics into their reconstruction plans. The resulting model even enabled Brian FG Katz, research director of the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) at Sorbonne University, to create a virtual reality version of Notre Dame with all the acoustical parameters in place.

A devastating fire

Flames and smoke billowing from the roof of Notre Dame cathedral in Paris on April 15, 2019. Credit: Pierre Suu/Getty Images

As we previously reported, Notre Dame’s roof and its support structure of 800-year-old oak timbers had almost completely succumbed to the flames. Firefighters reported the cathedral’s bell towers safe and said that many works of art had been rescued or were already stored in areas believed to be safe from the fire. The main spire—750 tons of oak lined with lead—collapsed in flames, landing on the wooden roof, which was destroyed. The trees that made up the roof’s wooden structure were cut down around 1160.

Thanks to the efforts of preservationists like Philippe Villeneuve, chief architect of historic monuments, the cathedral has been rebuilt nearly exactly as it was before the fire. The interior is most transformed since the walls, stained glass, paintings, and sculptures were all cleaned and restored for the first time since the 19th century. All the furnishings have been replaced, and sculptor and designer Guillaume Bardet was committed to creating a new altar and various liturgical items, including a new baptismal font and massive bronze altar. (The original stone altar was crushed as the collapsing spire plunged to the main floor.)

Much of the structural repairs will not be readily apparent to visitors, most notably the cathedral’s attic and roof, which were rebuilt with new hand-hewed timber trusses fixed in place by pegged mortise-and-tenon joints. One modern improvement: “Fire-resistant trusses at the crossing will isolate the spire and the two transept arms from the nave and the choir, so a fire can never again race through the entire attic,” Robert Kunzig wrote in the NatGeo article. “Should flames break out in this space, misters distributed throughout the attic will help suppress them until firefighters can climb hundreds of stairs.”

A photographer speaks

National Geographic was granted special access throughout the reconstruction process and tapped van Houtryve to capture everything in photographs and video footage. Ars caught up with him to learn more.

Designer Guillaume Bardet was hired to create a new bronze altar and pulpit, among other new liturgical furnishings. Credit: Tomas van Houtryve for National Geographic

Ars Technica: How did you get involved in documenting the cathedral’s restoration in photos/video?

Tomas van Houtryve: My journey in documenting the restoration of Notre-Dame de Paris began with an incredible opportunity through National Geographic’s partnership with Rebâtir Notre-Dame de Paris. I’ve always been drawn to the intersection of history and architecture, and I immediately knew I wanted to be a part of this project. It just so happened that through National Geographic and Rebâtir, I was able to perfectly combine my passion for visual storytelling with my deep connection to the city. Being entrusted to capture such a monumental effort felt like a natural progression in my career as a photographer—challenging, inspiring, and deeply meaningful.

Ars Technica: What were the biggest challenges in capturing this years-long process on camera?

Tomas van Houtryve: From a working standpoint, one of the biggest challenges was the high level of lead contamination. To be on-site, I had to wear a hazmat suit and often a respirator mask, which added a layer of physical difficulty to the work. Another significant hurdle was the heights. Thankfully, my background in rock climbing and the rope access training I completed with technicians proved invaluable. Once on-site, this assignment demanded every skill I’ve ever learned as a photographer. From flying drones in sensitive areas and mastering architectural photography to conducting the historic wet plate process with a 19th-century wooden camera, I applied everything in my visual toolbox. It was an all-encompassing challenge, but also an incredibly rewarding one.

Ars Technica: Was there any special equipment (lenses, cranes, etc.) needed to capture the photos and footage?

Tomas van Houtryve: It’s difficult to convey just how awe-inspiring the Notre-Dame de Paris restoration site is unless you see it in person. Stepping inside felt almost like entering a space station. There was an otherworldly blend of towering scaffolding, echoing sounds of the craftsmen at work, and the unique atmosphere of the cathedral itself. To document the restoration, I used a combination of modern and historic technology. Drones allowed me to navigate the intricate scaffolding and capture aerial perspectives that most people wouldn’t normally be able to see. And I also used a 19th-century wooden camera and portable darkroom to create glass plate photographs using the historic wet plate process. It was an incredible merging of the old and the new—a perfect representation of what Notre-Dame is and how it’s being restored.

Credit: Tomas van Houtryve for National Geographic

Ars Technica: What were some of the particular highlights for you as part of this long process?

Tomas van Houtryve: One of the standout highlights for me was witnessing the incredible craftsmanship that went into every detail of the restoration. Seeing the artisans, stonemasons, and carpenters recreate original elements with such precision and care was something that was very special. It gave me a deep appreciation for the skill and dedication involved in bringing Notre Dame back to life.

Another remarkable highlight was witnessing the transformation of the cathedral itself. Many people don’t realize that Gothic cathedrals like Notre-Dame de Paris were originally designed to be light, bright, and vibrant spaces of worship. Over centuries, time and human interaction dulled their appearance, creating the more imposing image we often associate with them. Seeing the cathedral fully cleaned, with its light stone walls restored to their original brilliance, felt like stepping back in time to another world. It was awe-inspiring to see the cathedral as it was meant to be, a true testament to its enduring beauty.

Ars Technica: As a Parisian, what has it meant to you to see Notre Dame restored to its former glory?

Tomas van Houtryve: Although I wasn’t born a Parisian, the years I’ve spent living here have made me feel deeply connected to this city—it’s my true home. On the night of the fire in 2019, every Parisian, including myself, watched in horror as our geographical epicenter—Notre-Dame de Paris—went up in flames. I’ll never forget it, and we’ve been haunted in some ways since then. Being trusted to photograph this monumental restoration, a feat of both engineering and unwavering passion, was not only a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, but it was cathartic. Contributing, even in a small way, to preserving the legacy of such an iconic symbol was both humbling and profoundly inspiring.

Credit: National Geographic

Jennifer is a senior reporter at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

A peek inside the restoration of the iconic Notre Dame cathedral Read More »