Radio telescope finds another mystery long-repeat source

File under W for WTF —

Unlike earlier object, the new source’s pulses of radio waves are erratic.

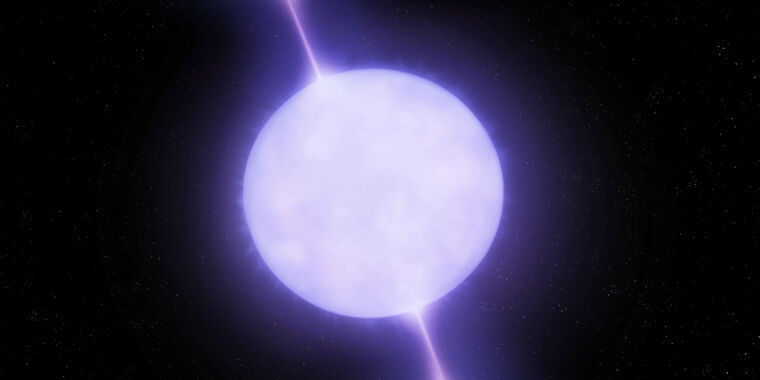

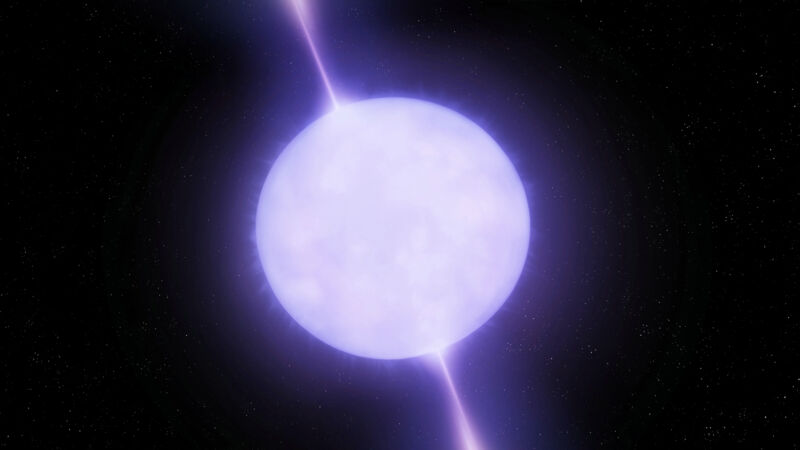

Enlarge / A slowly rotating neutron star is still our best guess as to the source of the mystery signals.

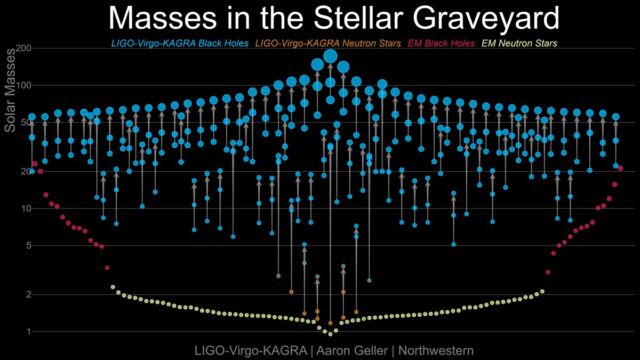

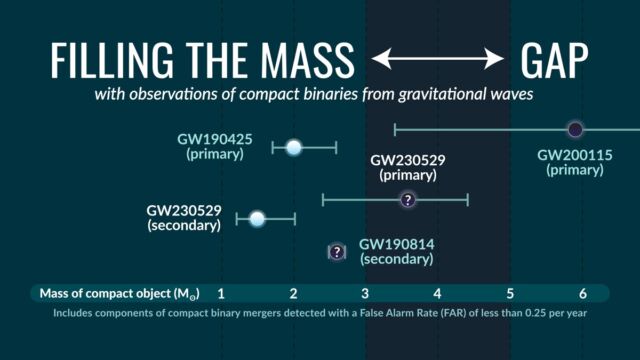

Roughly a year ago, astronomers announced that they had observed an object that shouldn’t exist. Like a pulsar, it emitted regularly timed bursts of radio emissions. But unlike a pulsar, those bursts were separated by over 20 minutes. If the 22 minute gap between bursts represents the rotation period of the object, then it is rotating too slowly to produce radio emissions by any known mechanism.

Now, some of the same team (along with new collaborators) are back with the discovery of something that, if anything, is acting even more oddly. The new source of radio bursts, ASKAP J193505.1+214841.0, takes nearly an hour between bursts. And it appears to have three different settings, sometimes producing weaker bursts and sometimes skipping them entirely. While the researchers suspect that, like pulsars, this is also powered by a neutron star, it’s not even clear that it’s the same class of object as their earlier discovery.

How pulsars pulse

Contrary to the section heading, pulsars don’t actually pulse. Neutron stars can create the illusion by having magnetic poles that aren’t lined up with their rotational pole. The magnetic poles are a source of constant radio emissions but, as the neutron star rotates, the emissions from the magnetic pole sweep across space in a manner similar to the light from a rotating lighthouse. If Earth happens to be caught up in that sweep, then the neutron star will appear to blink on and off as it rotates.

The star’s rotation is also needed for the generation of radio emissions themselves. If the neutron star rotates too slowly, then its magnetic field won’t be strong enough to produce radio emissions. So, it’s thought that if a pulsar’s rotation slows down enough (causing its pulses to be separated by too much time), it will simply shut down, and we’ll stop observing any radio emissions from the object.

We don’t have a clear idea of how long the time between pulses can get before a pulsar will shut down. But we do know that it’s going to be far less than 22 minutes.

Which is why the 2023 discovery was so strange. The object, GPM J1839–10, not only took a long time between pulses, but archival images showed that it had been pulsing on and off since at least 35 years ago.

To figure out what is going on, we really have two options. One is more and better observations of the source we know about. The second is to find other examples of similar behavior. There’s a chance we now have a second object like this, although there are enough differences that it’s not entirely clear.

An enigmatic find

The object, ASKAPJ193505.1+214841.0, was discovered by accident when the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder telescope was used to perform observations in the area due to detections of a gamma ray burst. It picked up a bright radio burst in the same field of view, but unrelated to the gamma ray burst. Further radio bursts showed up in later observations, as did a few far weaker bursts. A search of the telescope’s archives also spotted a weaker burst from the same location.

Checking the timing of the radio bursts, the team found that they could be explained by an object that emitted bursts every 54 hours, with bursts lasting from 10 seconds to just under a minute. Checking additional observations, however, showed that there were often instances where a 54 minute period would not end with a radio burst, suggesting the source sometimes skipped radio emissions entirely.

Odder still, the photons in the strong and weak bursts appeared to have different polarizations. These differences arise from the magnetic fields present where the bursts originate, suggesting that the two types of bursts differ not only in total energy, but also that the object that’s making them has a different magnetic field.

So, the researchers suggest that the object has three modes: strong pulses, faint pulses, and an off mode, although they can’t rule out the off mode producing weak radio signals that are below the detection capabilities of the telescopes we’re using. Over about eight months of sporadic observations, there’s no apparent pattern to the bursts.

What is this thing?

Checks at other wavelengths indicate there’s a magnetar and a supernova remnant in the vicinity of the mystery object, but not at the same location. There’s also a nearby brown dwarf at that point in the sky, but they strongly suspect that’s just a chance overlap. So, none of that tells us more about what produces these erratic bursts.

As with the earlier find, there seem to be two possible explanations for the ASKAP source. One is a neutron star that’s still managing to emit radiofrequency radiation from its poles despite rotating extremely slowly. The second is a white dwarf that has a reasonable rotation period but an unreasonably strong magnetic field.

To get at this issue, the researchers estimate the strength of the magnetic field needed to produce the larger bursts and come up with a value that’s significantly higher than any previously observed to originate on a white dwarf. So they strongly argue for the source being a neutron star. Whether that argues for the earlier source being a neutron star will depend on whether you feel that the two objects represent a single phenomenon despite their somewhat different behaviors.

In any case, we now have two of these mystery slow-repeat objects to explain. It’s possible that we’ll be able to learn more about this newer one if we can get some information as to what’s involved in its mode switching. But then we’ll have to figure out if what we learn applies to the one we discovered earlier.

Nature Astronomy, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02277-w (About DOIs).

Radio telescope finds another mystery long-repeat source Read More »