Don’t panic, but an asteroid has a 1.9% chance of hitting Earth in 2032

More data will likely reduce the chance of an impact to zero. If not, we have options.

Discovery images of asteroid 2024 YR4. Credit: ATLAS

Something in the sky captured the attention of astronomers in the final days of 2024. A telescope in Chile scanning the night sky detected a faint point of light, and it didn’t correspond to any of the thousands of known stars, comets, and asteroids in astronomers’ all-sky catalog.

The detection on December 27 came from one of a network of telescopes managed by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS), a NASA-funded project to provide warning of asteroids on a collision course with Earth.

Within a few days, scientists gathered enough information on the asteroid—officially designated 2024 YR4—to determine that its orbit will bring it quite close to Earth in 2028, and then again in 2032. Astronomers ruled out any chance of an impact with Earth in 2028, but there’s a small chance the asteroid might hit our planet on December 22, 2032.

How small? The probability has fluctuated in recent days, but as of Thursday, NASA’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies estimated a 1.9 percent chance of an impact with Earth in 2032. The European Space Agency (ESA) put the probability at 1.8 percent. So as of now, NASA believes there’s a 1-in-53 chance of 2024 YR4 striking Earth. That’s about twice as likely as the lifetime risk of dying in a motor vehicle crash, according to the National Safety Council.

These numbers are slightly higher than the probabilities published last month, when ESA estimated a 1.2 percent chance of an impact. In a matter of weeks or months, the number will likely drop to zero.

No surprise here, according to ESA.

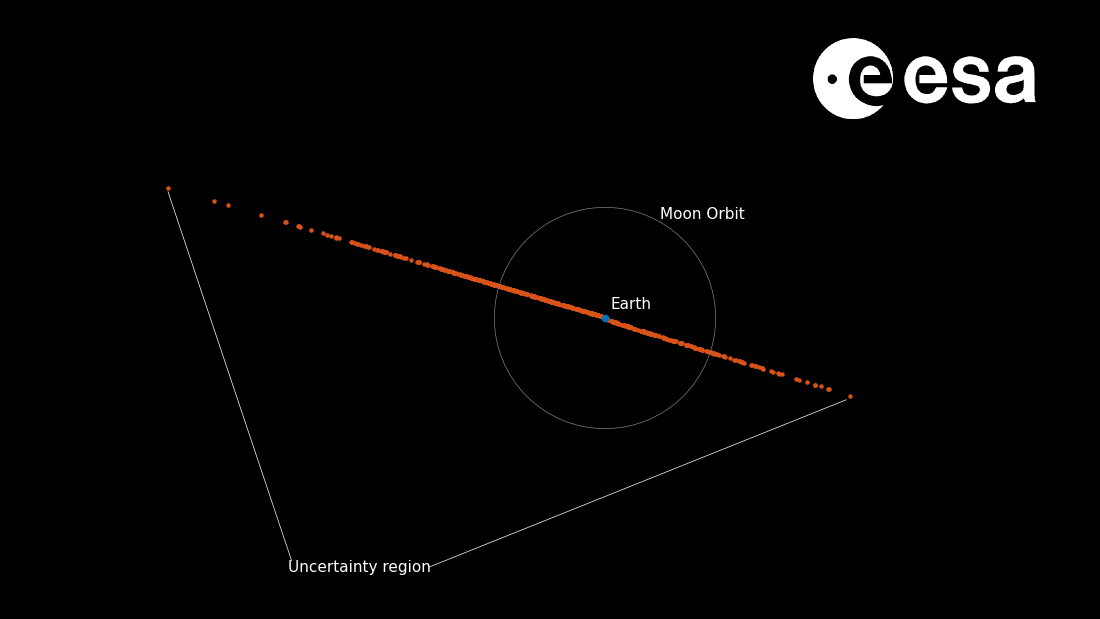

“It is important to remember that an asteroid’s impact probability often rises at first before quickly dropping to zero after additional observations,” ESA said in a press release. The agency released a short explainer video, embedded below, showing how an asteroid’s cone of uncertainty shrinks as scientists get a better idea of its trajectory.

Refining the risk

Scientists estimate that 2024 YR4 is between 130 to 300 feet (40 and 90 meters) wide, large enough to cause localized devastation near the impact site. The asteroid responsible for the Tunguska event of 1908, which leveled some 500 square miles (1,287 square kilometers) of forest in remote Siberia, was probably about the same size. The meteor that broke apart in the sky over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013 was about 20 meters wide.

Astronomers use the Torino scale for measuring the risk of potential asteroid impacts. Asteroid 2024 YR4 is now rated at Level 3 on this scale, meaning it merits close attention from astronomers, the public, and government officials. This is the second time an asteroid has reached this level since the scale’s adoption in 1999. The other case happened in 2004, when asteroid Apophis briefly reached a Level 4 rating until further observations of the asteroid eliminated any chance of an impact with the Earth in 2029.

In the unlikely event that it impacts the Earth, an asteroid the size of 2024 YR4 could cause blast damage as far as 30 miles (50 kilometers) from the location of the impact or airburst if the object breaks apart in the atmosphere, according to the International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN), established in the aftermath of the Chelyabinsk event.

The asteroid warning network is affiliated with the United Nations. Officials activate the IAWN when an asteroid bigger than 10 meters has a greater than 1 percent chance of striking Earth within the next 20 years. The risk of 2024 YR4 meets this threshold.

The red points on this image show the possible locations of asteroid 2024 YR4 on December 22, 2032, as projected by a Monte Carlo simulation. As this image shows, most of the simulations project the asteroid missing the Earth. Credit: ESA/Planetary Defense Office

Determining the asteroid’s exact size will be difficult. Scientists would need deep space radar observations, thermal infrared observations, or imagery from a spacecraft that could closely approach the asteroid, according to the IAWN. The asteroid won’t come close enough to Earth for deep space radar observations until shortly before its closest approach in 2032.

Astronomers need numerous observations to precisely plot an asteroid’s motion through the Solar System. Over time, these observations will reduce uncertainty and narrow the corridor the asteroid will follow as it comes near Earth.

Scientists already know a little about asteroid 2024 YR4’s orbit, which follows an elliptical path around the Sun. The orbit brings the asteroid inside of Earth’s orbit at its closest point to the Sun and then into the outer part of the asteroid belt when it is farthest from the Sun.

But there’s a complication in astronomers’ attempts to nail down the asteroid’s path. The object is currently moving away from Earth in almost a straight line. This makes it difficult to accurately determine its orbit by studying how its trajectory curves over time, according to ESA.

It also means observers will need to use larger telescopes to see the asteroid before it becomes too distant to see it from Earth in April. By the end of this year’s observing window, the asteroid warning network says the impact probability could increase to a couple tens of percent, or it could more likely drop back below the notification threshold (1 percent impact probability).

“It is possible that asteroid 2024 YR4 will fade from view before we are able to entirely rule out any chance of impact in 2032,” ESA said. “In this case, the asteroid will likely remain on ESA’s risk list until it becomes observable again in 2028.”

Planetary defenders

This means that public officials might need to start planning what to do later this year.

For the first time, an international board called the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group met this week to discuss what we can do to respond to the risk of an asteroid impact. This group, known as SMPAG, coordinates planning among representatives from the world’s space agencies, including NASA, ESA, China, and Russia.

The group decided on Monday to give astronomers a few more months to refine their estimates of the asteroid’s orbit before taking action. They will meet again in late April or early May or earlier if the impact risk increases significantly. If there’s still a greater than 1 percent probability of 2024 YR4 hitting the Earth, the group will issue a recommendation for further action to the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs.

So what are the options? If the data in a few months still shows that the asteroid poses a hazard to Earth, it will be time for the world’s space agencies to consider a deflection mission. NASA demonstrated its ability to alter the orbit of an asteroid in 2022 with a first-of-its-kind experiment in space. The mission, called DART, put a small spacecraft on a collision course with an asteroid two to four times larger than 2024 YR4.

The kinetic energy from the spacecraft’s death dive into the asteroid was enough to slightly nudge the object off its natural orbit around a nearby larger asteroid. This proved that an asteroid deflection mission could work if scientists have enough time to design and build it, an undertaking that took about five years for DART.

Italy’s LICIACube spacecraft snapped this image of asteroids Didymos (lower left) and Dimorphos (upper right) a few minutes after the impact of DART on September 26, 2022. Credit: ASI/NASA

A deflection mission is most effective well ahead of an asteroid’s potential encounter with the Earth, so it’s important not to wait until the last minute.

Fans of Hollywood movies know there’s a nuclear option for dealing with an asteroid coming toward us. The drawback of using a nuclear warhead is that it could shatter one large asteroid into many smaller objects, although recent research suggests a more distant nuclear explosion could produce enough X-ray radiation to push an asteroid off a collision course.

Waiting for additional observations in 2028 would leave little time to develop a deflection mission. Therefore, in the unlikely event that the risk of an impact rises over the next few months, it will be time for officials to start seriously considering the possibility of an intervention.

Even without a deflection, there’s plenty of time for government officials to do something here on Earth. It should be possible for authorities to evacuate any populations that might be affected by the asteroid.

The asteroid could devastate an area the size of a large city, but any impact is most likely to happen in a remote region or in the ocean. The risk corridor for 2024 YR4 extends from the eastern Pacific Ocean to northern South America, the Atlantic Ocean, Africa, the Arabian Sea, and South Asia.

There’s an old joke that dinosaurs went extinct because they didn’t have a space program. Whatever happens in 2032, we’re not at risk of extinction. However, occasions like this are exactly why most Americans think we should have a space program. A 2019 poll showed that 68 percent of Americans considered it very or extremely important for the space program to monitor asteroids, comets, or other objects from space that could strike the planet.

In contrast, about a quarter of those polled placed such importance on returning astronauts to the Moon or sending people to Mars. The cost of monitoring and deflecting asteroids is modest compared to the expensive undertakings of human missions to the Moon and Mars.

From taxpayers’ point of view, it seems this part of NASA offers the greatest bang for their buck.

Don’t panic, but an asteroid has a 1.9% chance of hitting Earth in 2032 Read More »