Saving up medical and health related stories from several months allowed for much better organizing of them, so I am happy I split these off. I will still post anything more urgent on a faster basis. There’s lots of things here that are fascinating and potentially very important, but I’ve had to prioritize and focus elsewhere, so I hope others pick up various torches.

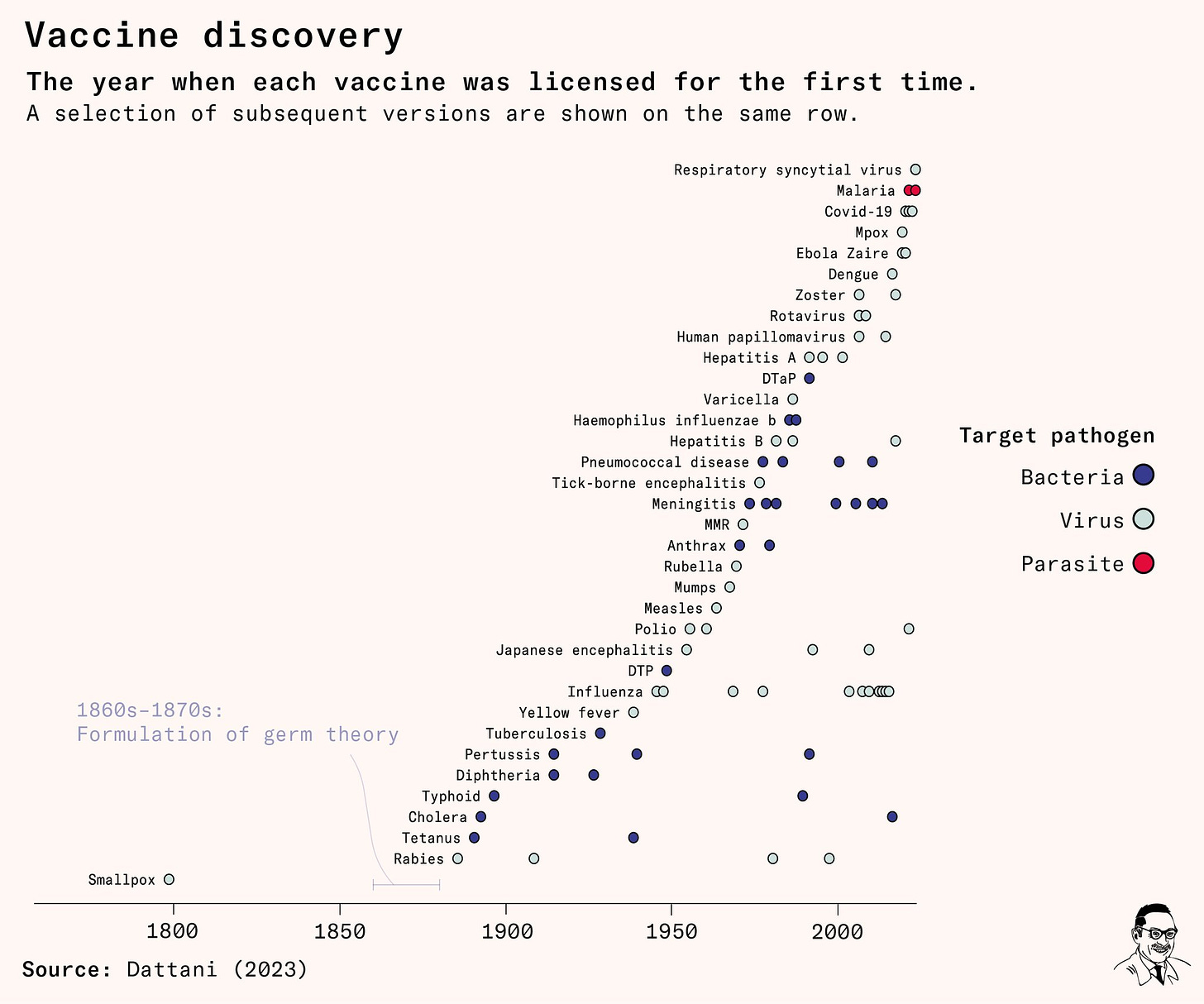

We have a new malaria vaccine. That’s great. WHO thinks this is not an especially urgent opportunity, or any kind of ‘emergency’ and so wants to wait for months before actually putting shots into arms. So what if we also see reports like ‘cuts infant deaths by 13%’? WHO doing WHO things, WHO Delenda Est and all that. What can we do about this?

Also, EA and everyone else who works in global health needs to do a complete post-mortem of how this was allowed to take so long, and why they couldn’t or didn’t do more to speed things along. There are in particular claims that the 2015-2019 delay was due to lack of funding, despite a malaria vaccine being an Open Phil priority. Saloni Dattani, Rachel Glennerster and Siddhartha Haria write about the long road for Works in Progress. They recommend future use of advance market commitments, which seems like a no brainer first step.

We also have an FDA approved vaccine for chikungunya.

Oh, and also we invented a vaccine for cancer, a huge boost to melanoma treatment.

Katalin Kariko and Drew Weissman win the Nobel Prize for mRNA vaccine technology. Rarely are such decisions this easy. Worth remembering that, in addition to denying me admission despite my status as a legacy, the University of Pennsylvania also refused to allow Kariko a tenure track position, calling her ‘not of faculty quality,’ and laughed at her leaving for BioNTech, especially when they refer to this as ‘Penn’s historic research team.’

Did you also know that Katalin’s advisor threatened to have her deported if she switched labs, and attempted to follow through on that threat?

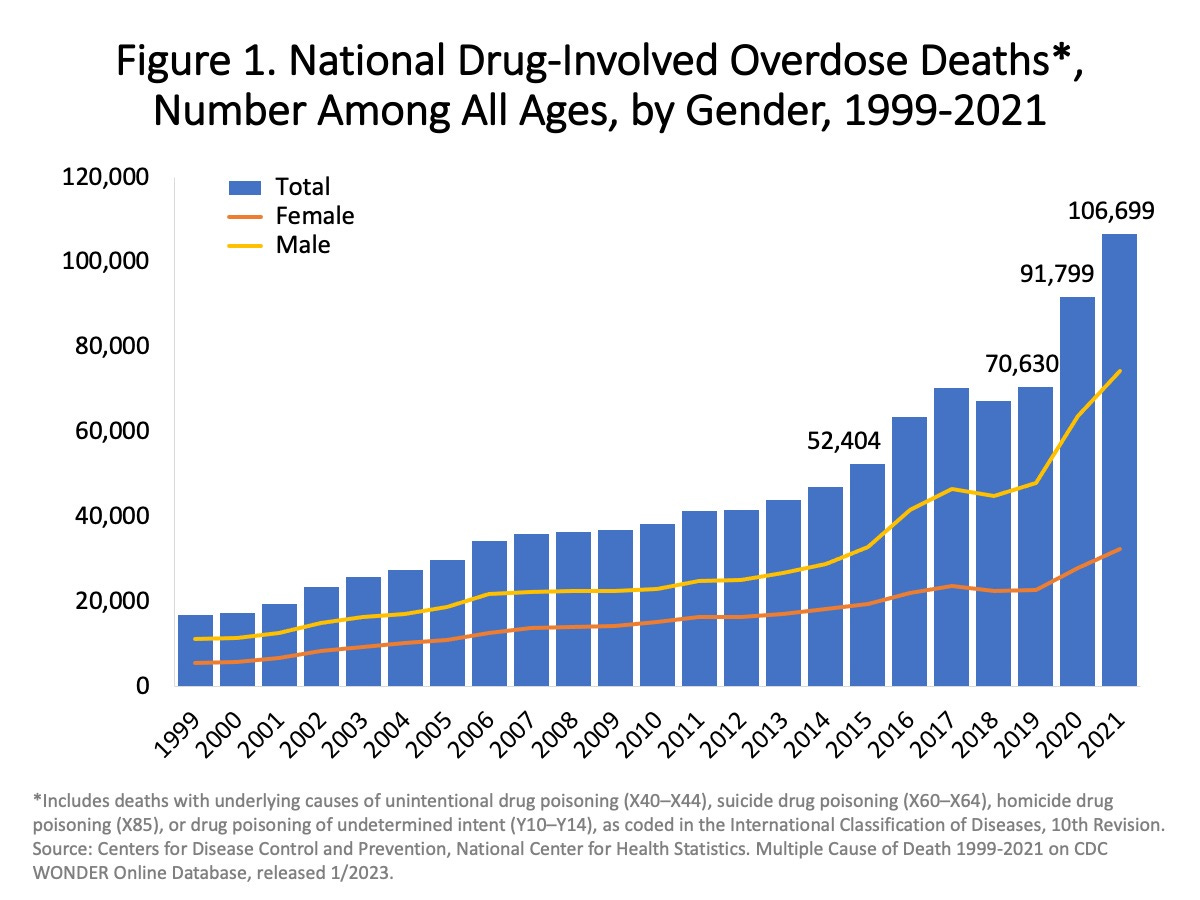

I also need to note the deep disappointment in Elon Musk, who even a few months ago was continuing to throw shade on the Covid vaccines.

And what do we do more generally about the fact that there are quite a lot of takes that one has reason to be nervous to say out loud, seem likely to be true, and also are endorsed by the majority of the population?

When we discovered all the vaccines. Progress continues. We need to go faster.

Reflections on what happened with medical start-up Alvea. They proved you could move much faster on vaccine development than anyone would admit, but then found that there was insufficient commercial or philanthropic demand for doing so to make it worth everyone’s time, so they wound down. As an individual and as a civilization, you get what you pay for.

Researchers discover what they call an on/off switch for breast cancer. Not clear yet how to use this to help patients.

London hospital uses competent execution on basic 1950s operations management, increases surgical efficiency by a factor of about five. Teams similar to a Formula 1 pit crew cut sterilization times from 40 minutes to 2. One room does anesthesia on the next patient while the other operates on the current one. There seems to be no reason this could not be implemented everywhere, other than lack of will?

Dementia rates down 13% over the past 25 years, for unclear reasons.

Sarah Constantin explores possibilities for cognitive enhancement. We have not yet tried many of the things one would try.

We found a way to suppress specific immune reactions, rather than having to suppress immune reactions in general, opening up the way to potentially fully curing a whole host of autoimmune disorders. Yes, in mice, of course it’s in mice, so don’t get overexcited.

From Sarah Constantin, The Enchippening of Medical Imaging. We are getting increasingly good not only at imaging, but imaging with smaller and more mobile and cheaper devices, opening up lots of new potential applications. An exciting time. As Sarah notes more broadly to open the series, making cheaper and better chips is the core tech behind pretty much everything getting continuously cheaper and better, and you should expect continuously cheaper and better from anything that relies on chips.

She also notes that Ultrasound Neuromodulation is potentially very exciting, especially if it can be put into a wearable. We could gain control over our mental state.

Claim that Viagra was significantly associated with a 69% reduced risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nice. There are supposed mechanisms involved and everything, the theory being direct brain health effects and reductions in toxic proteins that cause dementia. As opposed to the obvious interaction that Viagra users have more sex than non-users, which might protect against and definitely indicates against dementia.

Experts are, and I quote, warning us ‘not to get our hopes up yet.’

Amazon is now offering medical services, at very low prices. No insurance accepted.

Emily Porter, M.D.: Amazon is now offering chat medical visits (not even video) with physicians and NPs for $35 cash if you think you have COVID. Or a yeast infection. Or need birth control. How is this even considered healthcare? And why is it less expensive than my copay for my $700/mo BCBS PPO?

I want to jump in and say that I actually believe birth control should be OTC (plenty of my past tweets support that). But asthmatics, thyroid patients, those with high blood pressure, etc that Amazon is treating deserve affordable, accessible in-person care. This is suboptimal.

Armand Domalewski: Being able to chat with a doctor within 15 minutes for $30 is amazing. If you had told me this would be possible ten years ago I would’ve been blown away.

Seems great to me. Yes, if your only optimization target is optimal care and presume that everyone would otherwise get the full product, you will favor vastly more doctor attention, at vastly greater expense. However, if you instead realize that people’s time and money are things that matter to them and to society generally, which also means they will forgo medical consultations and treatments that cost too much of them. And also that we only have so many doctors (thanks AMA!) and thus only so many doctor hours to allocate, so if you waste them where they’re not valuable then someone else misses out, and that we do a lot of that allocation via time rather than price which is even worse. This is all very practical, a lot of people in the spots Amazon is offering a consult would instead have chosen no care at all under our existing system.

Health care would work so much better if we treated it as less sacred and more like Amazon treats its other products.

Economist reports (HT MR) that health insurance providers have a cap on direct profits, so they are buying health providers in order to steer customers to them, then paying those providers arbitrary prices. The incentives were already a nightmare, this makes them that much worse.

An interesting note is that Matthew Yglesias says he thought that this position was the consensus. It is simultaneously the consensus in the sense that people believe it, and also contrarian in the sense that the establishment and public health plan to do it all over again to the maximal extent possible and often act, like they and other cultural would-be authorities do on many things, as if anyone who defies the minority opinion they endorse too loudly is dangerous and terrible.

American Hearth Association releases new clinical tool that removes race as a factor in predicting who will have heart attacks or strokes. They decided that this is not a form of evidence they are willing to use, even though African-Americans suffer more heart attacks and strokes even when you control for everything else we know to measure. Not factoring this in means they will get less care. That doesn’t seem great.

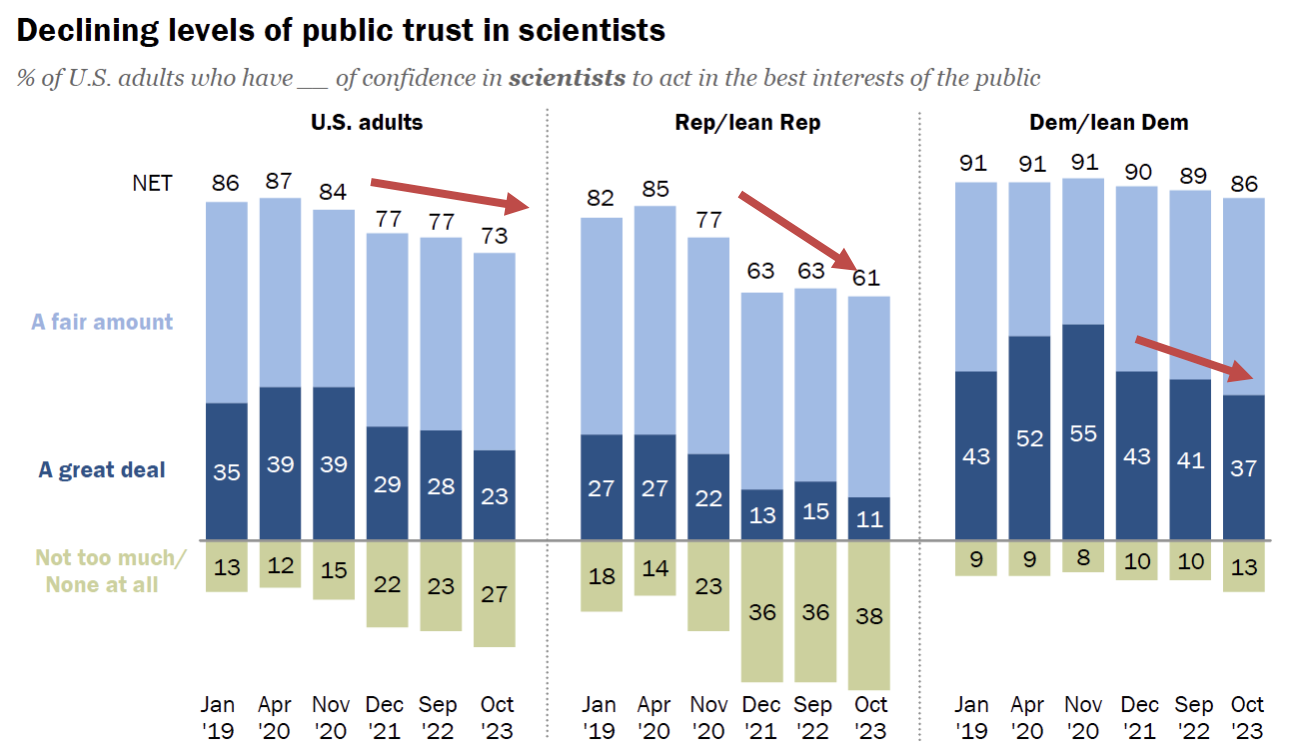

Dylan Matthews makes a convincing case that while deaths of despair and overdose deaths have increased, the bulk of the decline in American life expectancy so far has been due to problems with cardiovascular disease. It is also noted that the decline is focused on the worst-off locations and among high school dropouts, as opposed to being about whether you go to college.

So what matters is whether something in one’s early life is going very wrong. When that happens, we are letting such people down in many ways.

Not that the overdoses don’t matter. We have a rapidly growing, out of control problem with overdose deaths, and it is already having a real impact on life expectancy, and if it continues growing exponentially it will soon be far worse. It is scary as hell.

The right question to ask, as is often the case, is: Is this an ongoing exponential?

It looks exponential. It would be scary anyway since it is already almost 3% of deaths in 2021. What happens if it doubles again in the next decade?

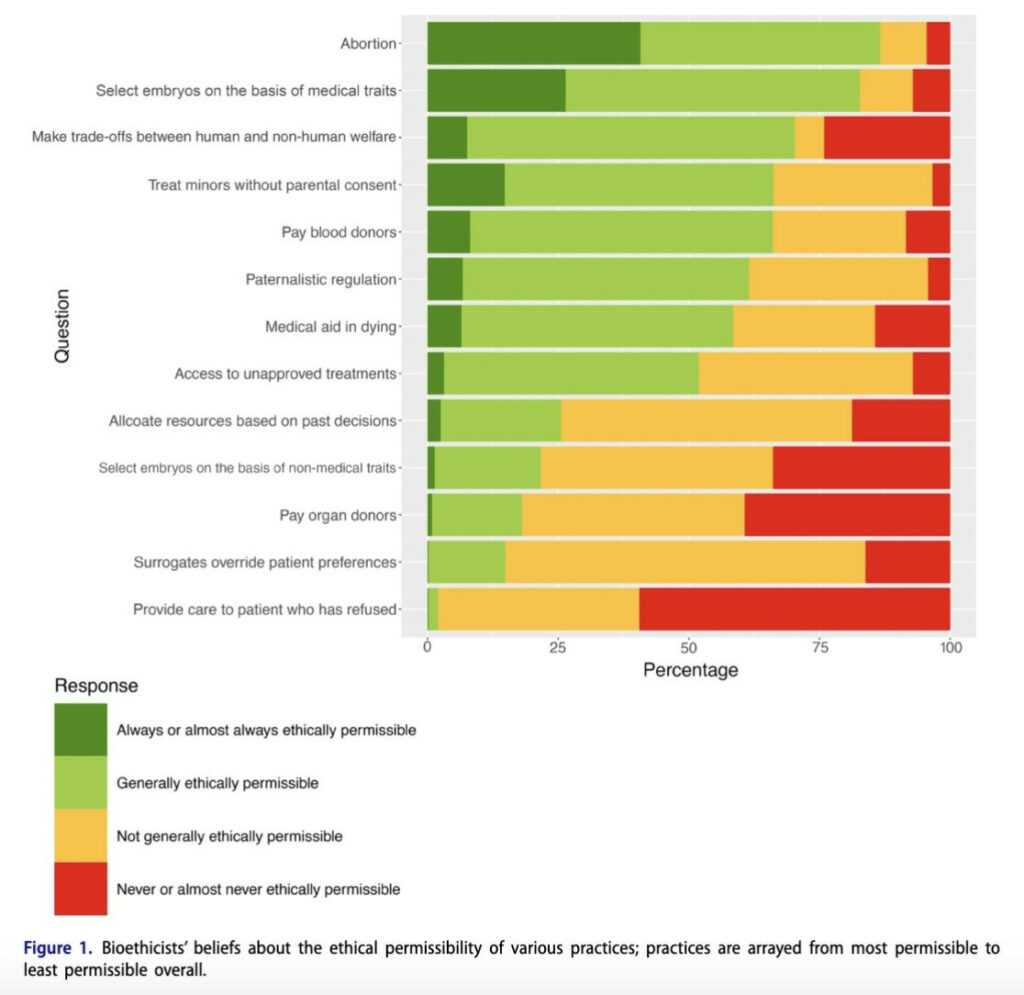

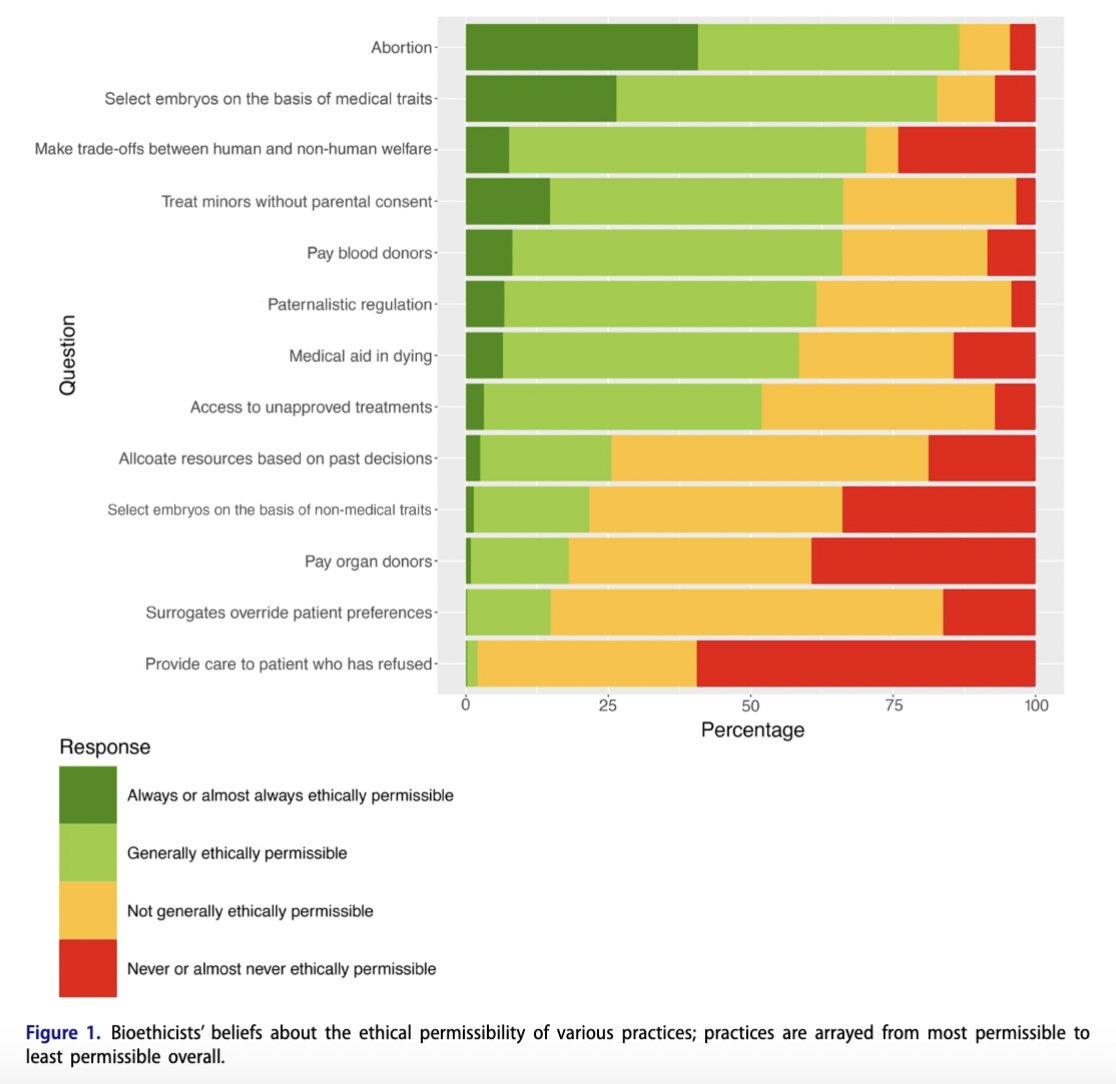

My mind still boggles that asking questions with the intent to learn or prove something requires ‘ethical’ clearance and worries about ‘potential harm’, and people keep endorsing this on reflection, burn it all to the ground.

Keller Scholl: The idea that asking people questions requires approval by an ethics board is a position unique to science/health. A YouTuber can do this and nobody bats an eyelash! But the moment you say you’re trying to do something other than entertain and profit, the “ethics people” arrive.

I want to differentiate them sharply from people who care about ethics, people who do serious ethical reasoning, etc. Primary marker is a bias towards inaction that is stronger when activity is for human advancement. Unlikely to be kidney donors personally.

amolitor.dolt: you kinda want *somethingthough. anyone should check that you’re literally just asking questions and not “while giving them electric shocks” or whatever. scientists get up to some shit if you don’t keep an eye on them.

Keller Scholl: “Asking people questions is fine. If you want to stick needles in them or lock them up, now you need approval from a peer committee with one or two outside voices” is a reasonable standard.

Yes. A simple safe harbor. If all you are doing is talking to people, or ideally also if you are otherwise doing things humans are allowed to do to other humans without any paperwork or checking for ‘informed consent’ then you don’t need any approvals. Even if you have the federal funding. Ask your questions.

A continuous problem is that the world desperately needs more common sense ethics and well-considered ethical considerations, and also that anyone who uses the word ‘ethics’ almost ever has anything to do with either of these things.

United Health pushed employees to follow an algorithm to cut off Medicare patients’ rehab benefits, says StatNews, to the tune of our way or the highway. If you want a ‘human in the loop’ the human needs to be able to determine the outcome of the loop. Here, it seems, they did not.

Yes, a lot of the reason Canadian health care is cheaper is that they sometimes tell you they’re not going to give you the surgery and instead suggest you consider assisted dying instead, whereas in America they will operate on you.

Tyler Cowen makes the case for a big push for hospital pricing transparency. As in, we need to insist on this like we insisted on ending the Vietnam War. The current situation is rather dire, as in things like this:

Recent research shows it is hard to even get a single consistent answer from a single provider. For instance, prices posted online and prices quoted over the telephone do not correlate very closely. For 41% of hospitals, the price difference was 50% or more. Clearly, suppliers aren’t really trying.

…

There is also a bipartisan health-care price transparency bill that was introduced last summer. President Joe Biden’s administration is proposing additional rule changes to further health care price transparency. Both are positive steps.

If all this sounds like too much government intervention, keep in mind the current non-transparent system is very much the product of ill-conceived government intervention, including regulations, entry barriers and trillions of dollars of public money. Most of those policies are not going away, so addressing these problems is going to involve some positive use of government. At the same time, a broader cultural revolution will be necessary.

Quite right on all counts. Government has decided for various reasons to intervene massively in the health care payments system, which is a central reason we lack price transparency. We need to use government to fix this, even if we do not use the first best solution of ‘get out of the way,’ and the benefits would be massive if we did fix it.

Paper claims working from home has negative mental health effects versus a workplace arrangement, although neither a big effect not anything like not working.

When considering all three dimensions of mental health together, WFH causes a 0.087 standard deviation increase in the overall measure of mental health deterioration compared to WP. Conversely, when compared to the NW option, WFH leads to a 0.174 standard deviation decrease in the overall measure of mental health deterioration.

In the context of a pandemic, working from home was probably relatively worse. My model is that the problem comes from isolation. If work was your only contact with the outside world you needed that. If not, you don’t.

Expiration dates are only, like, suggestions, man.

Kevin Kosar: News you can use: “Ah, but these food-safety regulations keep us safe, you might say. In almost all cases, there is no regulation and the dates do nothing to keep us safe.”

Scott Lincicome: An excellent @JoshZumbrun dive [in WSJ] into what I’ve been preaching for years now: so-called “expiration” dates are costly scam.

It took me blindly eating 5-month old yogurt live on camera (and lots of yelling) to do it, but I think I can finally now say it: I won.

The expiration dates are mandated only for infant formula. That does not mean they are useless, not net useful, or not protective of your health. Expiration dates are highly useful as they mark the relative freshness and remaining time of your items, and they provide reasonable approximations on how long various items can remain edible. Does that make them reliable markers of either spoilage or safety? No. It is a problem when sticklers treat them as gospel, again in either or both directions. I’m still glad they are there.

Scott Alexander notes that fully abolishing the FDA would require additional adjustments in the system. How would we deal with liability? What if doctors are stupid or fooled by advertising? How would prescriptions work or not work? How would insurance work? He comes down suggesting the FDA have a safety-only pathway for making drugs allowed, and legalization of artificial supplements.

That would be a reasonable practical compromise, but I think you can go a lot further. All these questions have reasonable answers. Prescriptions can continue where a sufficiently high bar is met, likely with a broader range of who can prescribe (e.g. a pharmacist should be fine for many but not all of them, so you don’t need an extra visit.) The other stuff will sort itself out the way it does everywhere else. Inspection agencies, for example, will rise up that do a better job for less money. Probably we do keep an FDA-like agency around for safety certifications due to liability concerns. To the extent other things wouldn’t fix themselves, it would mostly reveal rather than create those additional problems.

Again, I’d be happy to take Scott’s or another similar compromise. I still want to recognize it is far from first best.

The alternative is not abolishing the FDA and having stories like this?

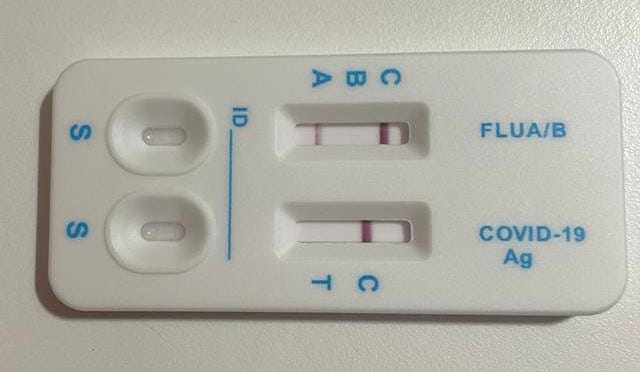

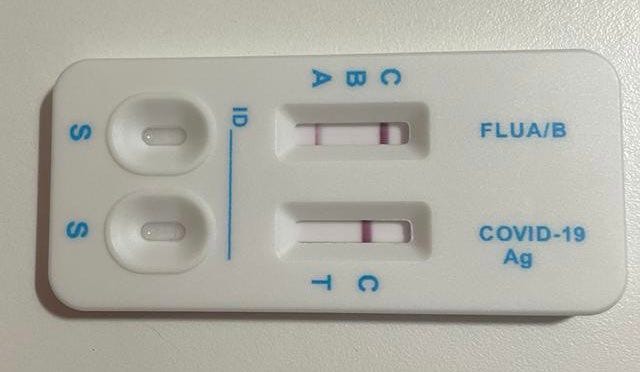

David Neary: A friend in Spain was feeling unwell and took a covid test. The good news is it’s not covid. The bad news it is the flu. The astonishing news is Spanish covid tests are dual-Covid/flu tests and why in the hell are these not available everywhere?!

Aaron: haha people might want to send home kids with the flu? lol fuck those people, right?

Medic Kim: Why don’t we have at-home antigen tests? Because the FDA panels are composed of these people:

A 2016 FDA advisory_panel, meanwhile, was split on whether the benefits of over-the-counter influenza tests outweighed the risks. Meeting transcripts show that as experts debated whether at-home tests would actually be effective at keeping people at home if they knew they or their children had the flu, one panelist joked that daycare centers might make the decision for parents if over-the- counter tests were available.

“The woman is going to want to go to work, and she wants to drop her kids off at daycare,” the panelist said. “The daycare, when they sign their contract, [could say] ‘If your kid has symptoms, we’re going to test him,” and send the child home if they tested positive.

The room laughed at the idea.

Chair: Looks like they were concerned abt the public’s inability to correctly assimilate false positive / false negative rates, resulting in harmful overconfidence in kit results.

So, yeah. I’ll take my chances with abolition.

Also, the FDA continues to move forward to regulate lab tests. As Alex Tabarrok says, it is vital that we do not let them, although by the time you read this it will be too late for public comment.

Also, why don’t your cold medicines work? Oh right.

John Arnold: Americans have been wasting billions a year on cold medicines like Sudafed & Benadryl with the active ingredient phenylephrine, despite conclusive evidence they don’t work. But a report published yesterday may finally lead to the removal of these drugs from pharmacy shelves.

FDA approval for these medicines was grandfathered without any clinical trial because the active ingredient was shown to be safe and to work if given intravenously. But, since approval, there have been 4 trials of oral form and all have shown no benefit vs placebo.

It’s a great example of the waste in the healthcare system that leads to high costs/poor outcomes. A vote next week will be a big test whether the FDA follows the science or caves to industry pressure.

The FDA has been monitoring these drugs since 2007 and finally ordered a formal review. From the report, posted yesterday: “We have now come to the initial conclusion that orally administered phenylephrine is not effective as a nasal decongestant.

The reviewers note the harms of continued sales:

– Unnecessary patient & total healthcare costs

– Delay in care

– Potential allergic reactions

– Overdosing given no response to recommended dosage

– Risk of use by children

– Missed opportunity for more effective treatment.

An advisory committee will vote next week whether to recommend removal of the drug from OTC use. If successful, it would go to the full FDA. Patients depend on the FDA to conduct rigorous analysis as to the efficacy of drugs. Let’s hope they correct this mistake.

Baron St. Rev Dr. von Rev: Reminder that fedgov allowed drug makers to substitute phenylephrine (which is useless) for pseudoephedrine in order to hamstring public opposition to their crackdown on the latter. It wasn’t a mistake, it was a con-job.

Will they finally fix it? I am not optimistic. They did vote 16-0 that there is no evidence that phenylephrine does not work.

If the system were otherwise sane, I would have zero problem with people selling a medicine that does not work. People could make their own choices. Alas, given the say the rest of the system works, permission, like retweets, here is an endorsement, and results in this preventing other actually effective treatment.

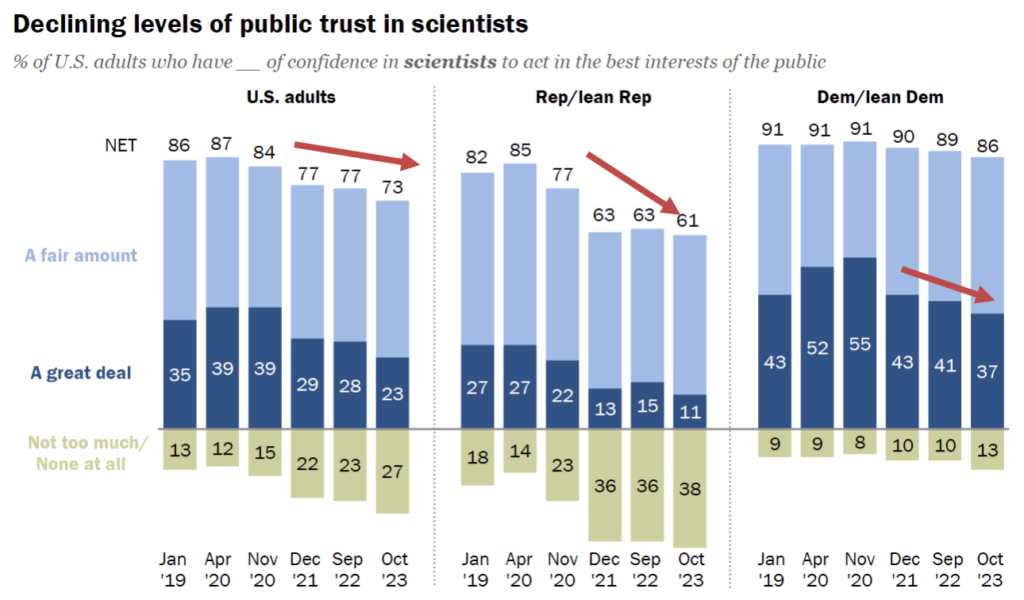

As Nate Silver reminds us, the Covid vaccine was the one thing that we know worked to prevent Covid deaths. Red states had 35% higher death rates than blue states once the vaccine was available, but had similar death rates before that despite less stringent countermeasures, so the effectiveness of all other measures remains unclear.

Former NIH director Francis Collins says the quiet parts out loud (1: 18 video, worth watching) regarding Covid policy and the public health mindset. They don’t think about the impact on the lives of ordinary people. They don’t do trade-offs or think about cost-benefit. They care only about lives saved, to which they attach infinite value.

I thank him for the clarity. Let this be common knowledge. Then let us never again entrust any future public health decisions to anyone with this ‘public health mindset.’

Instead, public health carries on as if they were right all along, even calling for us to mask up again every so often, and we sometimes see cases such as this one: San Diego State University to require Covid boosters in order to attend. Our colleges never learn, yet we expect them to teach us. What will we do about it?

Some good news on Covid is new claims that vaccination before first infection greatly.

Another good news note that hasn’t been noticed enough:

Steve Sailer: Here’s one observation about the contentious history of the pandemic I’ve never seen anywhere: Hospital managers turned out to be better at juggling their resources to keep their facilities from being overwhelmed than anybody had expected them to be.

This was the dog that did not bark. By all accounts, hospitals should have been far more overwhelmed, in ways that caused a lot more degradations in care and many excess deaths. Indeed, health care workers were constantly reporting hellish conditions, being put under unbearable pressures. Yet in the end, at least after the very early days, the center almost entirely held. We never properly thanked or honored those who pulled this off, in any form. Nor have we updated our future anticipations.

House passes ban on toddler mask mandates without a vote after opposition fails to provide any evidence whatsoever that masking toddlers is helpful. Took long enough. Turns out people say things are evidence-based without, ya know, evidence.

Several Republican Congressmen including Rubio told Biden on December 1 to ban travel from China to prevent mystery illness spread. And of course the person posting this was claiming there is no difference between this and lockdowns and this makes Republicans hypocrites. It doesn’t. It does make them wrong, in the sense that such a rule would have accomplished nothing even if the mystery illness had mattered – it is difficult imagine the world where such a ban stops the spread that would have otherwise happened. Luckily, we didn’t ban travel and everything is fine.

Nate Silver continues to be loud about the ‘Proximal Origins’ paper, the damage it and related efforts to convince us we could assume natural origins of Covid have done to trust in science, and in particular the lack of willingness to admit and call out what happened. He links to this post about it. Things do not look better over time:

Paul Thacker (from a larger thread): @USRightToKnow released documents showing virologists & Wuhan researchers attempted to mislead on a DARPA grant–they hid that they would do some dangerous virus research in Wuhan. Right where the pandemic started.

Nate Silver: This is quite bad. A group of virologists wanted to do gain-of-function research on COVID viruses in Wuhan in ways that closely matched the SARS-CoV-2 virus that’s killed 8+ million, but tried to hide the Wuhan linkages and got a lot of help in doing so from science journalists.

…

Idk COVID killed 8m people officially and tens of millions unofficially (based on excess deaths) and also profoundly disrupted nearly everyone’s well-being for 6-18 months, seems like a pretty important one compared to all the dumb shit people usually argue about.

The responses attempting to defend natural origin are all essentially ad hominem attacks at this point. The wrong person is advocating, why are you amplifying this bad person and bad theory, you do not know what you are talking about. Never arguments about the facts.

Here is a thread summarizing many pieces of evidence in favor of a lab leak.

If you want to engage with the debate, well, good news, it seems there is an 18 hour recorded debate, a third of which is published, six figures at stake on the outcome and a prediction market on the outcome.

Daniel Filan: One thing I’d like to emphasize: I think this is the best debate I have seen in my life. Object level informative, and worth wondering how to emulate. I genuinely wish political debates had this format.

I still am not about to watch hours of that.

The prior should not be low:

William Eden: The prior on lab leaks happening IS NOT LOW. It does NOT require extraordinary evidence for a lab leak being a source of an outbreak. This is always a reasonable hypothesis and *must be investigated*

Ian Birrell: New study reports 309 lab acquired infections and 16 pathogen lab escapes between 2000 and 2021

If we have almost one confirmed lab leak per year, and given the other circumstances, it would almost be surprising if Covid-19 wasn’t a lab leak.

Was Covid a lab leak? We don’t know. At this point it seems more likely than not.

That statement should drive huge changes in policy. A lot of people should be rethinking quite a lot of things. That is true even if (as I expect) we never know the answer for sure. This is very similar to the question of existential risk from AI. Any reasonable person, given the evidence, should say the lab leak has substantial probability, as does natural origin. Once you think the number is substantial, it does not much matter if your probability of the lab leak is 30%, 50%, 70% or 90%. They should drive most of the same changes in policy, and the same reflections. They won’t.

Imagine how we and you would have reacted if we had known, back in February 2020, that this virus had escaped from a lab. Then ask which parts of that reaction you would endorse on reflection, and which you do would not. Then act accordingly.

The good news is that it likely has succeeded in at least cancelling Deep VZN.

Jonatan Pallesen: The lab leak discourse has probably already succeeded in cancelling Deep VZN. An absurdly dangerous project where they would go and seek out the viruses most able to cause pandemics in humans. This alone makes it a debate that has achieved more than most others.

You think this is the worst that can happen? Well, remember that time Australian researchers were actively trying to create a ‘contraceptive mouse virus’ for pest control, which is totally not how any science fiction dystopia stories start, and they instead accidentally created a modified mousepox virus with 100% mortality? Check the linked thread out, because it keeps… getting… worse.

House unanimously votes to defund gain-of-function experiments with potential pandemic pathogens. I would prefer a ban, but unanimous support for at least not paying for it is a great start. Why am I worried this will still not get implemented?

Reducing third world lead poisoning continues to be a plausible high-value cause area.

Nathan Young: For a lack of, lets say, $1bn, half the children in poor countries have lead poisoning.

Jesse Copelyn in The Guardian: An estimated $350m in targeted aid from 2024 to 2030 would be enough to dramatically reduce lead exposure in lower-income countries, provided there is enough engagement from political leaders, according to the CGD. Funding requirements include donations for lead-testing equipment, support with advocacy and awareness campaigns, and technical assistance with drafting and enforcing regulations.

Statements like Nathan’s require caution and careful calibration. I very much doubt a billion dollars would put a stop to all the lead poisoning. How much would it reduce such lead poisoning for how many children, with how much impact? I have no idea. I find it likely that $1 billion well-spent on this would be a good use of funds. I also can think of ways one could plausibly spend that money badly, and it ends up wasted or even making things worse.

Seriously, let’s buy out the patent rights and offer these drugs for free to anyone who wants them, what are we waiting for. New EA cause area.

Belarusian comedian hits it big with comedy routine (YouTube, 1: 04: 00) in which he complains he will die of old age and calls upon everyone to focus on maybe stopping this from happening.

Robert Wiblin: Paying people in exchange for their blood is very bad — but saying misleading things so they’ll give you their blood for free is very good.

The expected QALYs from you donating blood is more like 0.01 rather than the 200 which they’re suggesting. Still a good thing to do but you can’t save 3 lives in an hour.

Excellent, I don’t remember seeing a good estimate before, 0.01 seems highly sane. So that’s about three days of life. A very good thing to do, definitely donate blood. Very, very different from three lives in an hour, not even the most outlandish EA earning-to-give and cost-per-life-saved statistics claim anything close to that.

Rob Bensinger: Seems like one of the more important facts about our civilization — we live in the world where paying people is seen as taking advantage of them, while lying to people is seen as normal and OK. (In a surprisingly large number of cases.)

I think a lot of what’s going on is that “was money exchanged?” is a relatively discrete and legible question, whereas “was a falsehood stated?” is often a lot fuzzier, depending on how vague language is interpreted, and on where you draw various lines.

An eight year old watching a webcam feed can tell with confidence whether money was exchanged, typically.

Whereas the entire Earth’s resources, science, and technology can’t necessarily reach a confident verdict about whether Alice’s “I’m fine” statement is strictly true. (Even Alice may not be confident!)

So bureaucracies have a much easier type setting actionable policies about money than about truthfulness. And individual humans have a far easier time rationalizing their preferred conclusion about “was X true?” than about “was Y paid?”.

The end result being that bureaucracies end up with all sorts of wacky rules about money, because humans have emotional hang-ups about Everything and money is an easy thing to regulate.

Whereas even the most scrupulous bureaucracy will tend to lie a lot, because this is harder to regulate and incentive gradients toward lying abound: you fudge the truth a tiny bit and it helps, then you fudge it slightly more…

I doubt anyone in the bureaucracy ever had the conscious thought “it’s OK to fudge the truth and deceive people, but not OK to pay them”. Lying and paying people are just very standard human behaviors, and of those “paying people” is a lot easier to regulate.

Want to get more people to donate? Yes, you could and should pay them. There is some price at which you’ll get plenty of donations, it will be cheap versus health gains, and those that get the money will be better off.

But also I once again iterate to those in charge of blood donations: By requiring appointments, you are greatly raising the effective cost of donations. If you could take walk-ins, even confirmed right beforehand on the web, I would happy do this much more often. If I have to block out an appointment time days in advance, that’s so much harder.

That change fits well within the ‘ethics’ requirements. All you have to do is provide a place I can walk in on a whim and donate, or go when there is urgent need. I’ll do it.

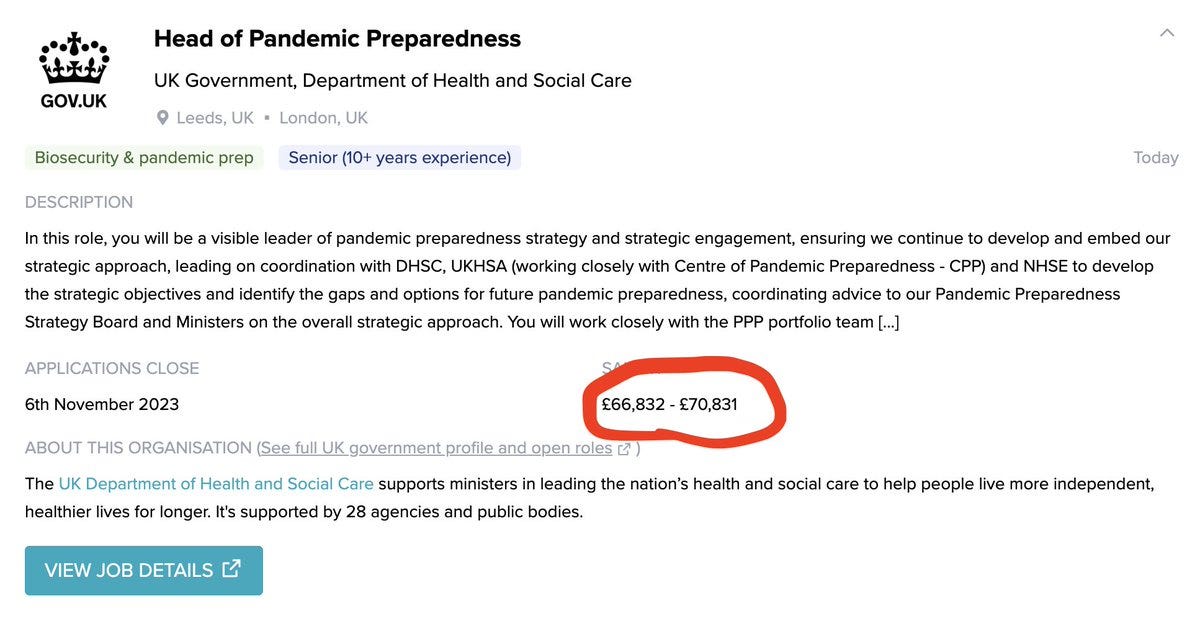

You know who else you should pay? The head of UK pandemic preparedness.

Alex Tabarrok: What’s the chance it could happen twice? ¯_(ツ)_/¯

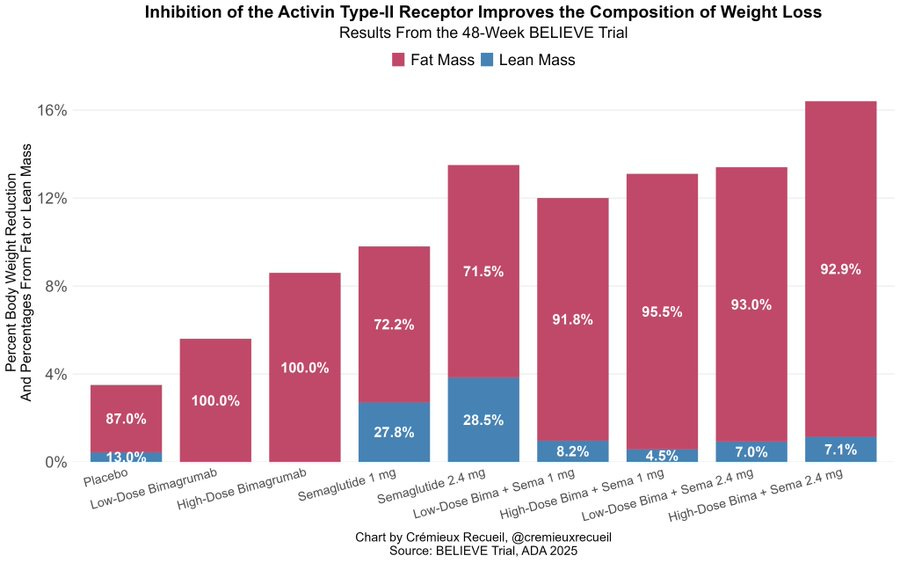

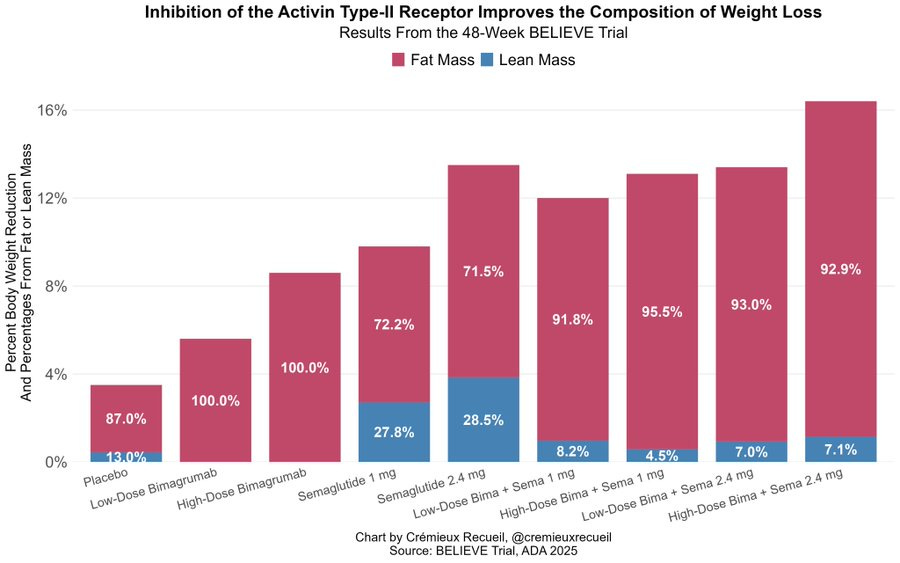

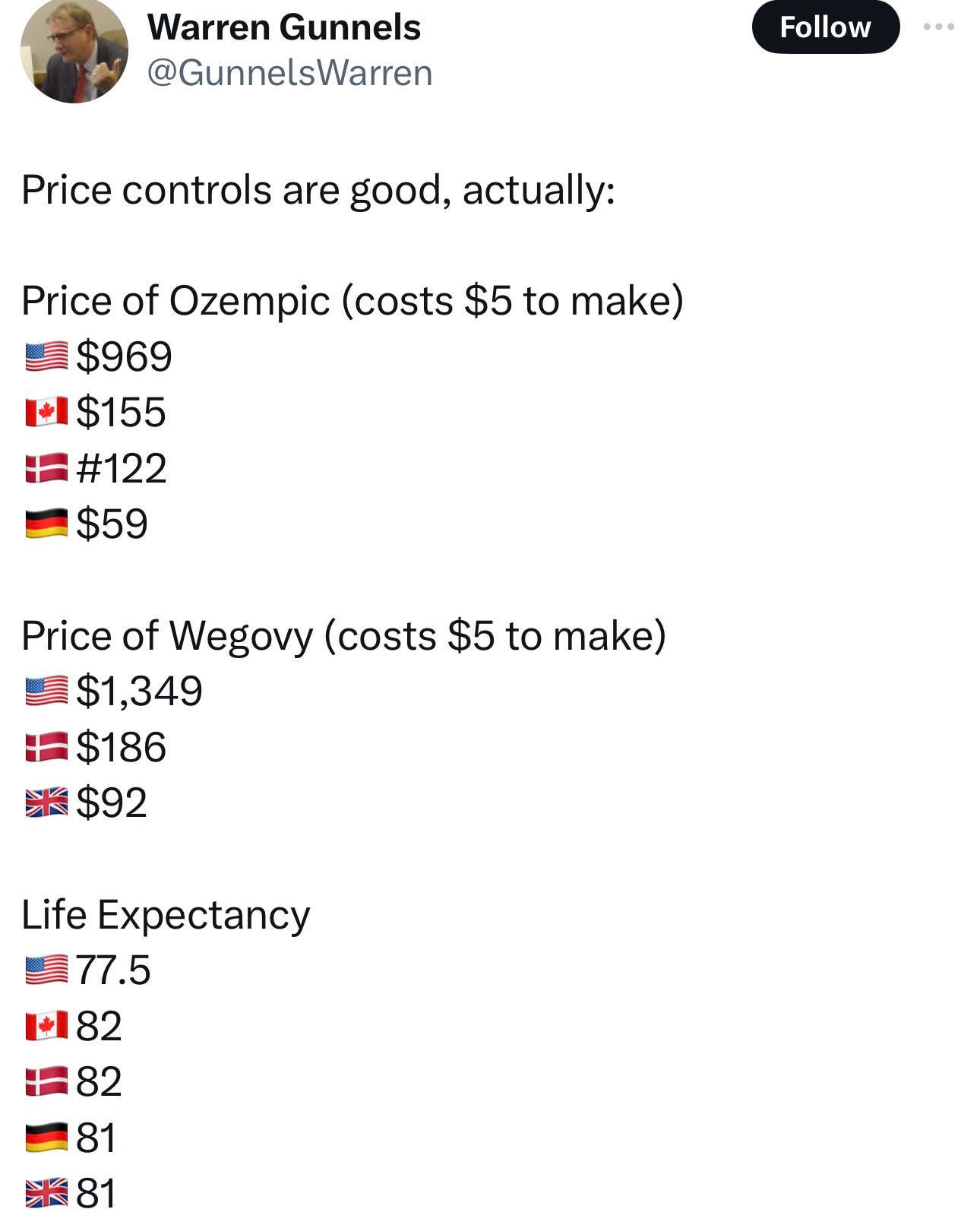

Wegovy (a GLP-1 antagonist) cut the rate of major heart problems in a 17k patient trial – heart attack, stroke, or cardiovascular-related death by 20%. It also cut all-cause mortality by 19%, which I would have led with, with no major side effect issues. Wow.

Market Monetarist thinks GLP-1s are a huge economic deal.

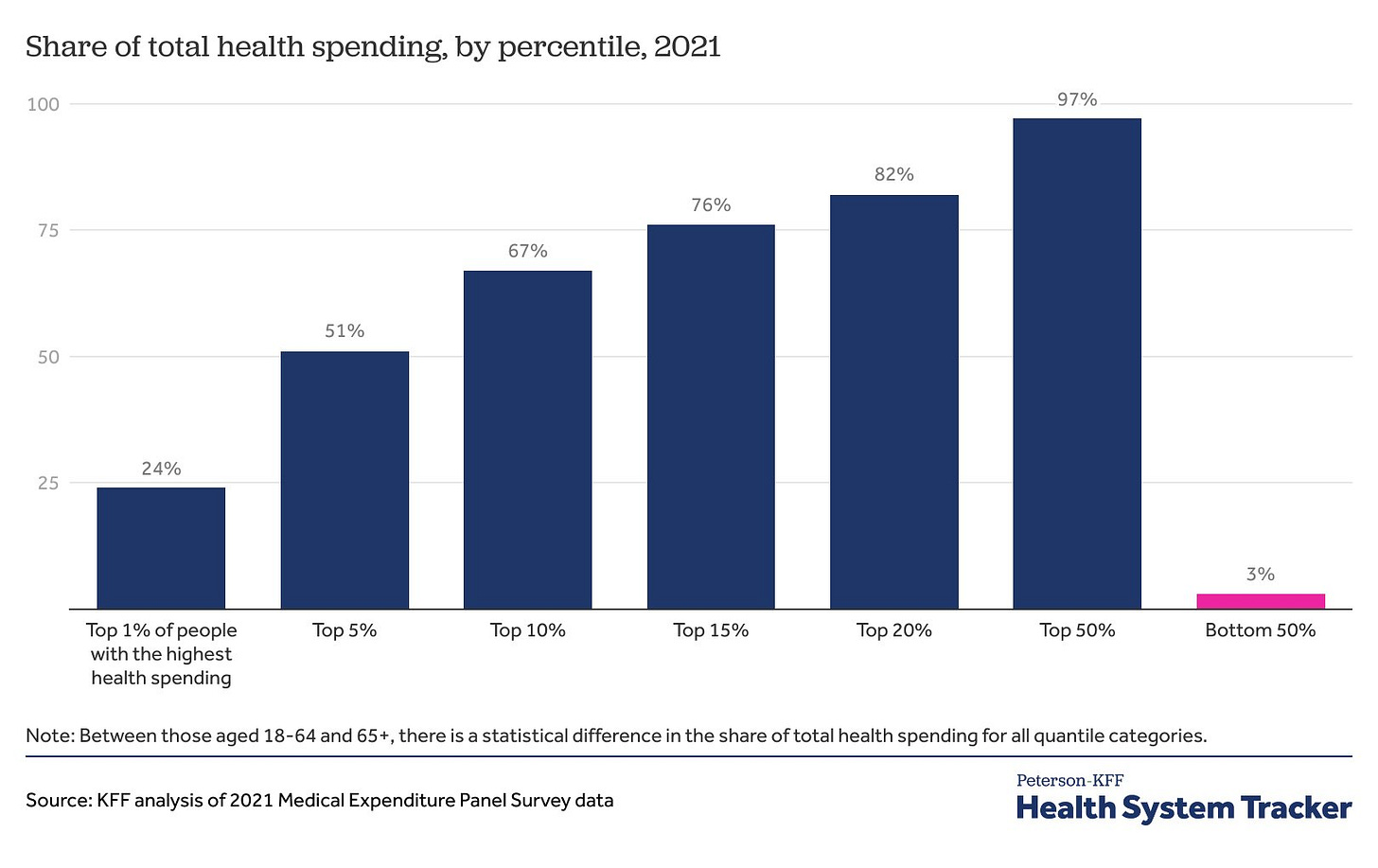

Obesity, particularly severe obesity, involves enormous healthcare costs. In the United States, the rate of obesity has increased markedly since the 1980s. Now, approximately 40% of the population is obese, leading to stagnation in average life expectancy and making obesity-related diseases like diabetes and heart disease among the leading causes of death.

A Danish study from 2021 showed that healthcare costs for obese individuals are double those for individuals of normal weight, significantly contributing to the national healthcare burden in Denmark. The reduction of severe obesity through medications like Ozempic and Wegovy could provide a substantial economic boost.

America spends more than 17% of GDP on health care. If GLP-1s reliably cure obesity, and obesity doubles health care costs, and 42% of Americans are obese, the math says that you could in theory reduce health care costs by almost 30%, saving almost 6% of GDP.

That is a huge game, if and only if that spending does not then get reallocated to providing more care to others. If our health spending is determined more by wealth than medical need, as it seems largely to be, most of that would be wasted on additional marginal care of little value.

The actual health benefits, of course, would be very real, including productivity.

Obese individuals are also less productive, more likely to be unemployed, and earn lower wages. This translates into substantial economic impacts, such as higher rates of work absenteeism among severely obese workers compared to their normal-weight counterparts.

A reduction in obesity in the U.S. could lead to an improvement in the economy. Halving the number of obese individuals could result in a 2% increase in overall wages and a significant rise in GDP if we assume as numerous studies shows that obese women have salaries 10% lower than normal weight women (corrected to age, education and experience).

I would be cautious attributing too much of the earnings differential to productivity. The beauty premium is real, discrimination against ugly or fat people is rampant, and these are likely to largely be positional effects.

Still, there are obviously large real productivity gains to better health.

There are also big productivity gains to general impulse control. GLP-1 inhibitors help with a wide variety of addictive and unproductive behaviors. My presumption is you would see substantial productivity gains.

How best to think about what Ozempic (another GLP-1 antagonist) does?

Cate Hall: Ozempic doesn’t provide willpower; it eliminates the need for it. These might sound like similar things but the internal experience is wildly different, as any addict can tell you.

Andy Jung: Translation: it doesn’t give you the willpower to overcome unhealthy urges. It eliminates the urges. Really interesting…powerful, but ultimately a shortcut.

Cate Hall: Hell yeah, we love shortcuts!

Emmett Shear: Will power basically doesn’t exist as far as I can tell?

Cate Hall: I think that’s a defensible position. It’s certainly at least a confused concept. I would probably say willpower in the sense of gritty determination exists, but in application doesn’t look anything like what “alcoholism is just poor willpower” folks think.

I think this is one of those places where willpower is a confused concept when you look at it too carefully, but acting like it does not exist or is not important will only leave you far more confused. I find it wise to treat willpower as if it is real.

How much adaptation will we see? It is easy to do the math on every obese person taking Ozempic. It is a lot harder to get that to happen, or anything approaching that.

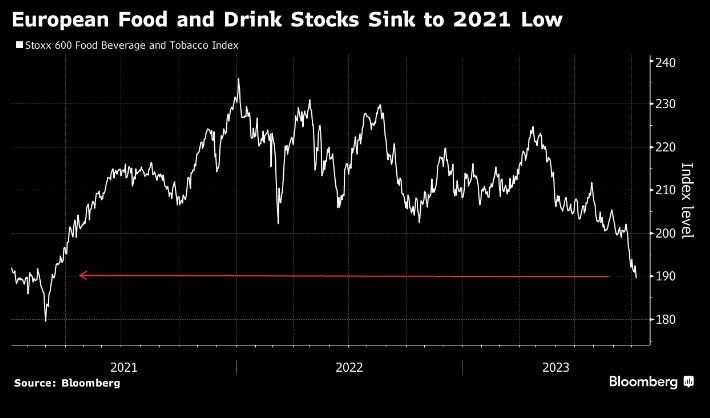

Ozempic might be driving a selloff in candy and beer stocks, with the caveat that of course one must never reason from a price change.

Genevieve Roch-Decter: Weight loss drug Ozempic causing selloff in candy and beer stocks, per Bloomberg. Walmart said it’s already seeing an impact on shopping demand from people taking Ozempic. That sent shares of food and beverage companies sliding, some to multiyear lows. Crazy.

This is super exciting. As with AI, this part of the future remains highly unevenly distributed, and is orders of magnitude more expensive than it will be soon.

Tenobrus: it turns out ozempic is also the cure for doomscrolling and tiktok

Ava: something amazing about the fact that we invented things we’re incapable of consuming in moderation and then invented something that removes our ability to enjoy them.

It looks like GLP-1s reduce alcoholism, which on its own is a huge freaking deal.

Does… this… work? Issue hasn’t come up for me in a while:

Iva Dixit: Constantly stupefied at how if I google a medication name with the word “coupon” and show the pharmacist the first result from a shady looking spammy site — 90% of the time it works and the medicine’s price goes from $283 to $31.

I have just been told that if I get this medicine delivered via their home delivery program it’s $60 and if I want to come pick it up myself then it’s $142 ………………. big pharma are you guys ok.

I mean, I googled ‘Ozempic coupon’ as a test – note that these are very much the opposite of verified – Henry Meds claims to be selling a GLP-1 antagonist at $300/month, Calibrate claims even less, GoodRx has modest (~10%) discounts off the bat.

Also does this work? A public service announcement blast from the past.

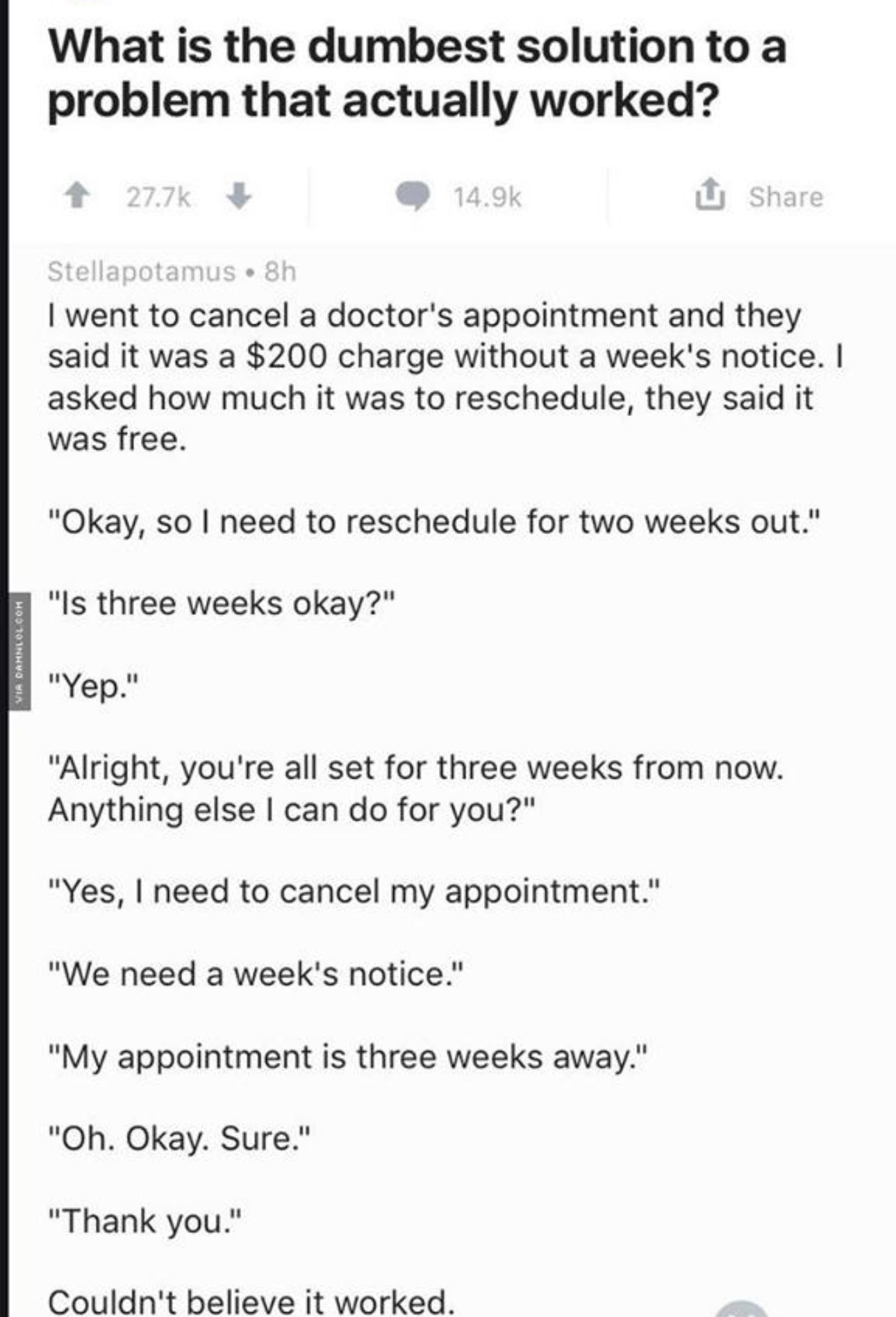

Karandeep Singh: The more friction that exists in US healthcare, the more that innovation ends up looking like this 👇

Matt Yglesias shares his experience losing weight via bariatric surgery. He found it easy to lose weight up to a point, but that past that point he continued to struggle with the same urges to eat more and eat unhealthy and not be active. He’s excited for the GLP-1 inhibitors. One worthy note he makes is that if you have an unhealthy relationship to food, fixing it is (usually, for most people, myself included) not a matter of ‘eat like a healthy person,’ the same way an alcoholic can’t drink like a normal person. You have to do something far more intentional and deliberate, more absolute, more costly, and do it constantly forever. The other is that he sees anticipation that doctors will lecture fat people that they should lose weight as a big barrier to them effectively getting any other treatment for problems their weight makes worse – not only don’t they want to hear it, the doctors often refuse to offer alternative help. Which is terrible, and doctors should of course stop it, especially the not helping with alternatives. Yet we also would be wise to find ways not to generally fool ourselves into thinking that unhealthy weights are healthy.

An epic and righteous rant about how much people obsess over vegetables and what is rightfully called morality-based dietary planning. Eigenrobot’s 100-year-old grandfather is literally starving to death because his grandmother keeps insisting on these elaborate ‘healthy’ meal plans that took him hours to consume, when instead it turns out you can just feed the guy stuff like ice cream and he can get it down fine, and obviously that is what any sane person would do in this spot.

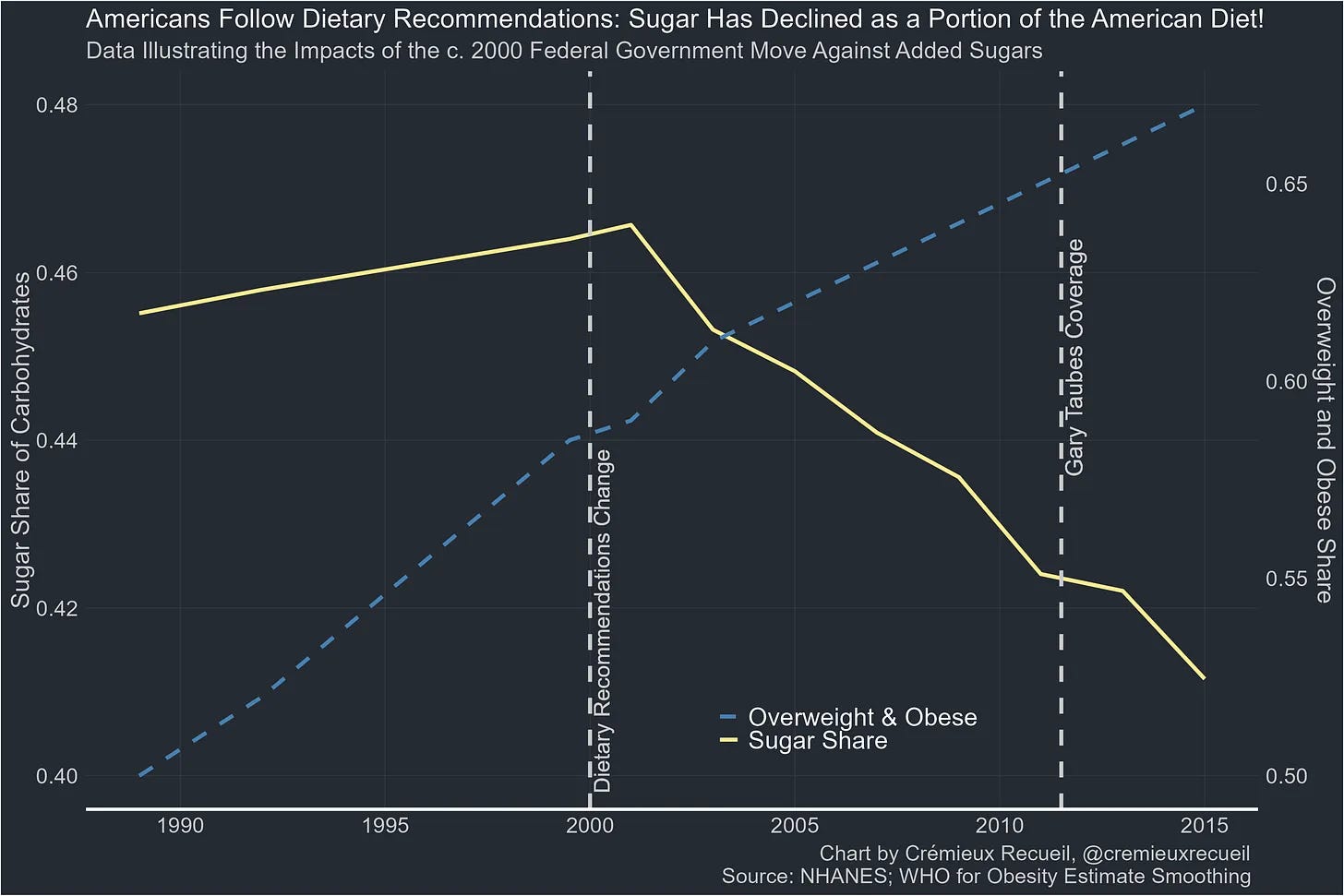

My model is that we know four things about nutrition with any certainty:

-

Different people work very, very differently here.

-

There are things you need, often but not always your body lets you know.

-

Vegetables good.

-

Sugar bad.

How important are rules two and three? Great question. We don’t know that.

I’ve been unable to eat fruits or vegetables in most forms for my whole life, unless they are very tiny or heavily processed. My body does not believe they are food and I will literally gag and choke on them. The few ways I can sometimes eat one almost never bring me any joy, only melancholy and sorrow. People constantly worried about this for a long time, and I haven’t been able to fix it. I don’t worry much about this anymore, and you know what? It’s fine.

On rule three, my revealed preference is ‘enough to eat less sugar than I otherwise would, not enough to not eat a lot of sugar anyway.’ I endorse this on reflection.

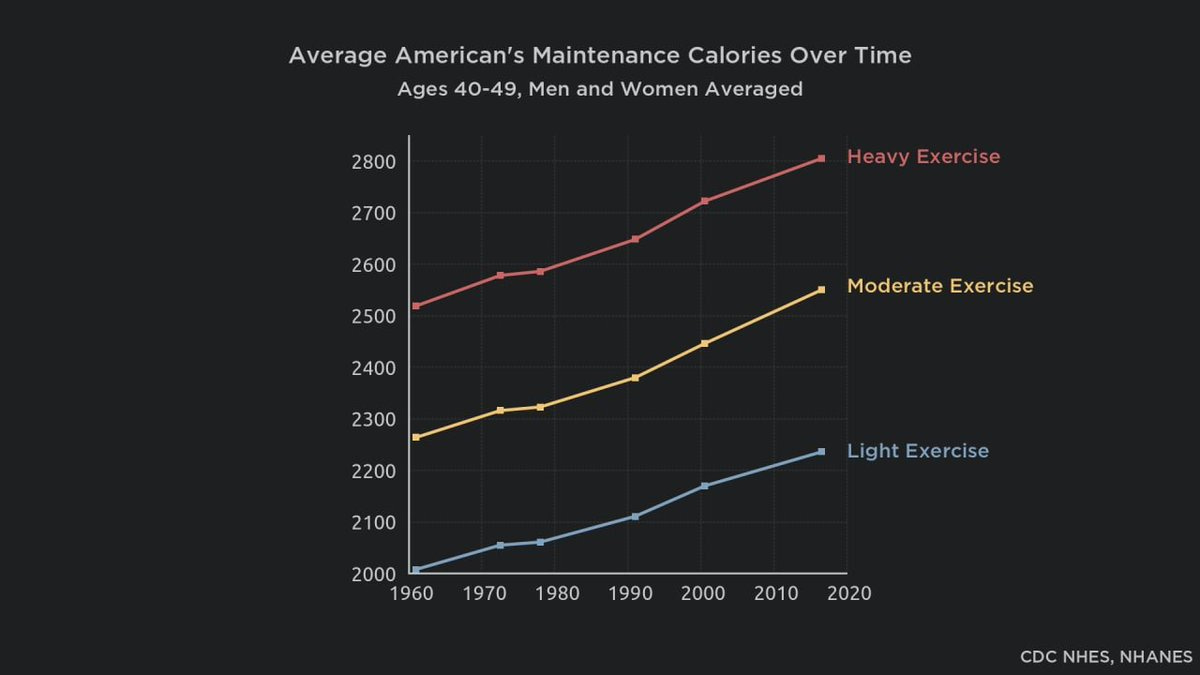

What are the returns to exercise? Roger Silk does some math, attempting to think like an economist.

His basic model is to assume that we value 16 waking hours per day only, exercise costs time now, and it pays off with additional time in the future. He then asks, if a program of 9 hours gives a 50-year-old the chance to live to 88 instead of 80, what is the rate of return? He finds 5.8%, with returns up to 6.5% for smaller investments, so the marginal return on the final hours is likely more like 4%.

Is that a good investment? As Roger points out, there is no inflation in years. If all things were fully equal, and all that mattered was my personal time discounting, and I thought I ‘lived in normal times’ so to speak so postponing my actions didn’t impact the world nor would the world much change, I would take essentially any positive return.

What key considerations are being ignored in the calculation here?

-

Correlation is not causation. Exercise is claimed to be ‘associated’ with 8 extra years of life. But it is trivial to see why this is almost certainly an overstatement of the causal effect of choosing more exercise. Choosing to do more and better exercise is associated with good health through direct causation, and also associated with most other good habits and attributes. A brief look at the study indicates no effort to account to properly control for these problems.

-

Exercise has major positive impacts other than lifespan. This is the reason why I am able to motivate myself to exercise. If it was purely lifespan, I would not trust that the rate of return was positive. But when I exercise, I have more energy, I feel better, I look better, I can eat more, life is good. That is a huge deal.

-

Exercise can be good or bad in many other ways. Are you using up willpower or generating more? Learning to form good habits, or using up your habit budget? Does this make you more interesting and confident, or less interesting and overconfident? Do you start loving life, or start hating life? Different people get different results, on top of the considerations I mentioned earlier.

-

As is noted, what kind of years are you getting? Are you getting extra healthy years, extra aged years on the end, or a slowing of the aging process? How exactly does this all supposedly work? You are investing your best remaining years now (at least if we are assuming you are at least 25 now), in terms of health, to get years later. If the average future year quality doesn’t change, you are downgrading quite a bit on health. You could make some of it up with wisdom and wealth.

-

You could also make up for it via future technology. If you expect technology to extend our lifespans over time, then buying time becomes more valuable. If you expect escape velocity, expected returns could suddenly look very, very good. Same if you think that new tech will make life a lot better in at least some worlds. If I am alive in 2054, then chances are some really awesome tech is available.

-

The time you spend exercising is not worth zero. If you hate it, it could be strongly negative. If you find something you like, or a way to like it, it can be substantially positive. I have yet to find exercise I actively enjoy that I can sustain (I started to like running then my knees gave out), but I have at times found exercise where the net experience is positive due to ability to watch television or listen to podcasts while doing it, or to chat with my trainer.

-

We do not have 16 flexible, valuable hours to spend each day. There are a lot of fixed costs beyond sleeping that eat into our time. Where is your exercise time going to come from? The more your joy is contained in your copious free time, and the more of that this would eat, the higher the effective price. When I was working at Jane Street, it was a relatively high effective cost in time to work out, whereas now as a writer it is relatively less.

-

Risk of injury is a real thing, with exercise both causing it directly and preventing it indirectly. I recently took out my back for a few weeks while doing squats in the wrong way, that is important lost time.

Also, the real story of people not exercising is pretty damn simple. Mostly true story.

Afro—Arakkii Leo Says Resist: most people don’t exercise because it’s fucking boring dude. That’s it. It’s literally boring as hell. Especially things like weightlifting, which is 9/10 times just grinding for vanity reasons. And people are always going to be iffy about it until we normalize play as exercise.

Most people don’t want to just go to some sweaty building and hate their bodies into something society deems acceptable like you know what would be great for heart health? Tag. We should all go to the park and play tag.

But i’m so sick of gym bros shitting on people for not wanting to exercise like bro….this shit isn’t natural. Picking heavy things up over and over again to look bigger is something we just made up! And it’s not even fun!

I would take the under on 90% vanity. A lot of working out is for the right reasons. But yes, working out is mostly unpleasant and boring as hell as we conceive of it and we need to stop pretending otherwise. Once we agree that most exercise mostly bores most people who try it out of their minds, we can work on not doing that.

Well, maybe. From a certain point of view.

Matthew Yglesias takes a stand against dentistry. Well, maybe not quite against dentistry writ large, but against the current regime of dentists being a cartel taking a large cut of every cleaning, not letting others diagnose conditions, and the only insurance available being a product that does not insure one against large dental bills, while not providing evidence for its interventions working.

Studies show, he says, that letting dental hygienists work on their own improves dental health, in addition to improving equality and lowering costs. The mechanism is that if routine dental services cost more, you will consume less of them.

The insurance thing is its own complaint and also pretty weird every time I think about it. In medicine you want to buy medical catastrophic insurance and are forced to also buy coverage on pain of them charging you artificially high prices to punish you. In dentistry, you cannot buy the insurance at all even together with the coverage, only partial coverage of routine costs.

Most interesting is the claim that dentistry is not evidence based.

Matthew Yglesias: Dental medicine is practiced with almost no scientific evidence, making it a huge field of opportunity for grifts and scams.

The Matthew Principle (no relation I think): I’ve had similar experiences: went to a dentist once and was told I had seven (!) cavities. Went to another and was told there were just two.

Adrienne: This happened to my mom. Went to a new dentist and was told she needed about $7,000 of work. Got a second opinion, and nothing was wrong.

Alicia Smith: Friend of mine went to the dentists and was told she had 3 cavities since her last visit a year ago. She went and got a 2nd opinion before getting these cavities filled, and was told she has no cavities at all.

[comments full of people who don’t trust dentists not to defraud them.]

Matt Yglesias (in his post): Some people, of course, are not that ethical. And even those who are ethical are naturally going to find themselves inclined in the direction of self-interest when dealing with an evidentiary void. William Ecenbarger did a great investigative report for Readers’ Digest years ago where he visited dentists in different cities and asked for their recommendations and got prescribed courses of treatment ranging from $500 to $25,000. One outfit in Philadelphia diagnosed him this way: “Tell me what your insurance limits are, and we’ll proceed from there.”

Back at Vox, I used to work with Joey Stromberg (whose dad is a dentist), who wrote a piece about how “while seeing other dentists, my brother has been told he needed six fillings that turned out to be totally unnecessary (based on my dad’s look at his X-rays) and I’ve been pressured to buy prescription toothpaste and other products I didn’t need.” Aspen Dental appears to have built a whole corporate dental chain around the observation that you can attract patients with low prices and then make it up in volume by prescribing unnecessary treatments.

Yglesias also quotes Ferris Jabr in the Atlantic here:

The Cochrane organization, a highly respected arbiter of evidence-based medicine, has conducted systematic reviews of oral-health studies since 1999. In these reviews, researchers analyze the scientific literature on a particular dental intervention, focusing on the most rigorous and well-designed studies. In some cases, the findings clearly justify a given procedure. For example, dental sealants—liquid plastics painted onto the pits and grooves of teeth like nail polish—reduce tooth decay in children and have no known risks. (Despite this, they are not widely used, possibly because they are too simple and inexpensive to earn dentists much money.) But most of the Cochrane reviews reach one of two disheartening conclusions: Either the available evidence fails to confirm the purported benefits of a given dental intervention, or there is simply not enough research to say anything substantive one way or another.

And perhaps it gets worse? Here’s MF Bloom quoting the AP saying there is no evidence that flossing works. The government seems to have agreed that no one has ever properly researched the question. The AP looked and its findings where that the evidence is “weak, very unreliable” and of “very low” quality. Ouch.

Does flossing do something? It is a physical action, so we can tell that it does literally do something. But does that something translate into better dental health? We do not know. It would be unsurprising to me either way. I can also see why there could be no one party with the incentive to study this properly and find out.