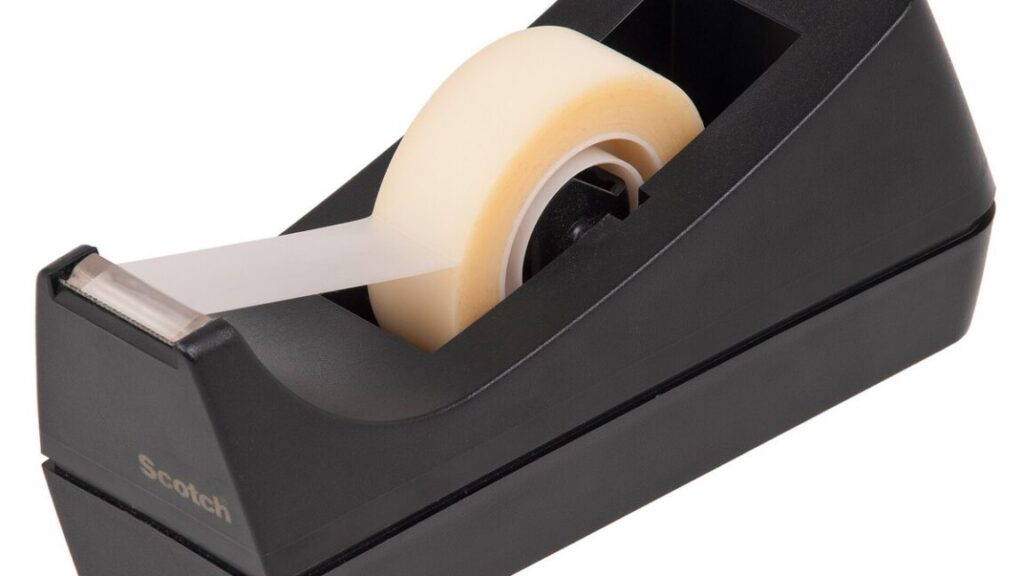

Scientists crack the case of “screeching” Scotch tape

In 1953, Russian scientists peeling Scotch tape in a vacuum reported detecting electrons with sufficient energy to emit X-rays. Other scientists were skeptical, but this phenomenon was finally confirmed in 2008, when UCLA physicists produced X-rays while unwinding a roll of Scotch tape in a vacuum chamber. The goal was to harness triboluminescence for X-ray imaging, and the team produced a low-quality X-ray image of a lab member’s finger (see image below). Fortunately, this only works in a perfect vacuum, so everyday Scotch tape users are safe.

A shock to the system

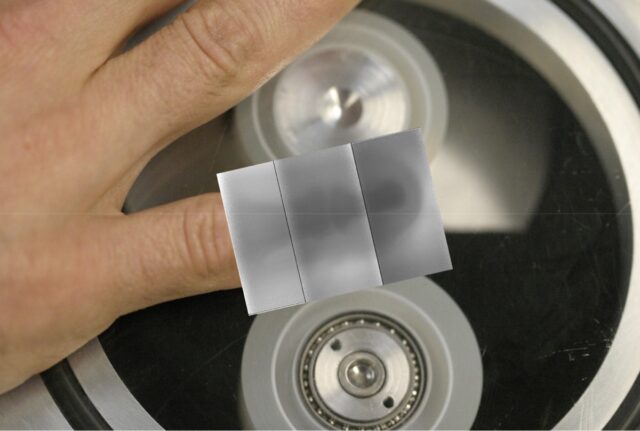

X-ray images of a human finger taken with peeling tape. Credit: Carlos G. Camara et al., 2008

Peeling Scotch tape produces sound as well as light, typically attributed to the slip-stick mechanism at play during the peeling process. In 2010, co-author Sigurdur Thoroddsen of King Abdullah University in Saudi Arabia and colleagues used ultra-fast imaging to identify a crucial micro-fracture phenomenon of the slip mechanism: a sequence of transverse cracks that travel across the width of the adhesive at supersonic speeds. A follow-up 2024 study found a direct correspondence between the screeching sound and those transverse cracks, but did not identify a mechanism.

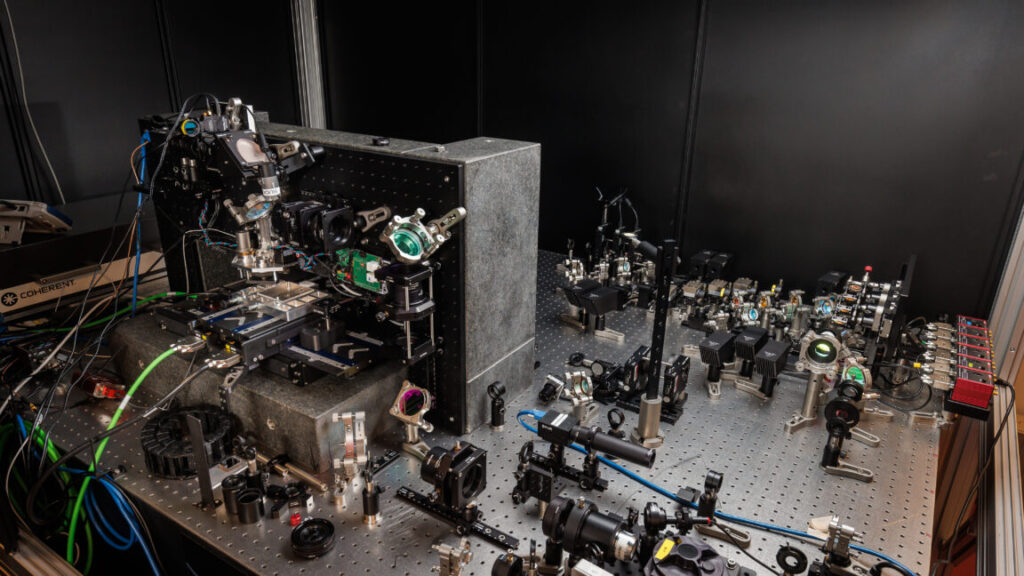

That is the purpose of this latest study. Thoroddsen et al. wondered whether the sound was directly generated by a crack’s rapidly moving tip, which would also produce the distinctive discrete sound wave pulses associated with peeling Scotch tape. The authors experimentally tested their hypothesis by conducting simultaneous high-speed imaging of the propagating fractures and the sound waves traveling in the air. They manually unpeeled Scotch tape using a metal rod, capturing the cracks with two video cameras and the sound with two microphones synchronized to the video camera, the better to pinpoint the origin of the pressure pulses.

Their results showed that the screeching arises from a train of weak shocks that culminate when the transverse cracks reach the edge of the tape. The supersonic speed at which they travel, relative to the surrounding air, is crucial to the generation of those shockwaves. “A partial vacuum is produced between the tape and the solid when the crack opens,” the authors explained. “The crack moves too fast for this void to be filled immediately, even though air is sucked in from the direction perpendicular to the crack. The void therefore moves with the crack until it reaches the end of the tape and collapses into the stationary air outside.” Each time a fracture tip reaches the edge of the tape, it generates a sound pulse—hence the telltale screech.

DOI: Physical Review E, 2026. 10.1103/p19h-9ysx (About DOIs).

Scientists crack the case of “screeching” Scotch tape Read More »