What if the aliens come and we just can’t communicate?

Ars chats with particle physicist Daniel Whiteson about his new book Do Aliens Speak Physics?

Science fiction has long speculated about the possibility of first contact with an alien species from a distant world and how we might be able to communicate with them. But what if we simply don’t have enough common ground for that to even be possible? An alien species is bound to be biologically very different, and their language will be shaped by their home environment, broader culture, and even how they perceive the universe. They might not even share the same math and physics. These and other fascinating questions are the focus of an entertaining new book, Do Aliens Speak Physics? And Other Questions About Science and the Nature of Reality.

Co-author Daniel Whiteson is a particle physicist at the University of California, Irvine, who has worked on the ATLAS collaboration at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. He’s also a gifted science communicator who previously co-authored two books with cartoonist Jorge Cham of PhD Comics fame: 2018’s We Have No Idea and 2021’s Frequently Asked Questions About the Universe. (The pair also co-hosted a podcast from 2018 to 2024, Daniel and Jorge Explain the Universe.) This time around, cartoonist Andy Warner provided the illustrations, and Whiteson and Warner charmingly dedicate their book to “all the alien scientists we have yet to meet.”

Whiteson has long been interested in the philosophy of physics. “I’m not the kind of physicist who’s like, ‘whatever, let’s just measure stuff,’” he told Ars. “The thing that always excited me about physics was this implicit promise that we were doing something universal, that we were learning things that were true on other planets. But the more I learned, the more concerned I became that this might have been oversold. None are fundamental, and we don’t understand why anything emerges. Can we separate the human lens from the thing we’re looking at? We don’t know in the end how much that lens is distorting what we see or defining what we’re looking at. So that was the fundamental question I always wanted to explore.”

Whiteson initially pitched his book idea to his 14-year-old son, who inherited his father’s interest in science. But his son thought Whiteson’s planned discussion of how physics might not be universal was, well, boring. “When you ask for notes, you’ve got to listen to them,” said Whiteson. “So I came back and said, ‘Well, what about a book about when aliens arrive? Will their science be similar to ours? Can we collaborate together?’” That pitch won the teen’s enthusiastic approval: same ideas, but couched in the context of alien contact to make them more concrete.

As for Warner’s involvement as illustrator, “I cold-emailed him and said, ‘Want to write a book about aliens? You get to draw lots of weird aliens,’” said Whiteson. Who could resist that offer?

Ars caught up with Whiteson to learn more.

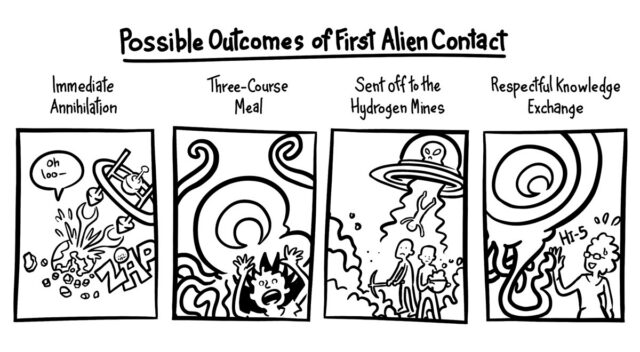

Credit: Andy Warner

Ars Technica: You open each chapter with fictional hypothetical scenarios. Why?

Daniel Whiteson: I sent an early version of the book to my friend, [biologist] Matt Giorgianni, who appears in cartoon form in the book. He said, “The book is great, but it’s abstract. Why don’t you write out a hypothetical concrete scenario for each chapter to show us what it would be like and how we would stumble.”

All great ideas seem obvious once you hear them. I’ve always been a huge science fiction fan. It’s thoughtful and creative and exploratory about the way the universe could be and might be. So I jumped at the opportunity to write a little bit of science fiction. Each one was challenging because you have to come up with a specific example that illustrates the concepts in that chapter, the issues that you might run into, but also be believable and interesting. We went through a lot of drafts. But I had a lot of fun writing them.

Ars Technica: The Voyager Golden Record is perhaps the best known example of humans attempting to communicate with an alien species, spearheaded by the late Carl Sagan, among others. But what are the odds that, despite our best efforts, any aliens will ever be able to decipher our “message in a bottle”?

Daniel Whiteson: I did an informal experiment where I printed out a picture of the Pioneer plaque and showed it to a bunch of grad students who were young enough to not have seen it before. This is Sagan’s audience: biological humans, same brain, same culture, physics grad students—none of them had any idea what any of that was supposed to refer to. NASA gave him two weeks to come up with that design. I don’t know that I would’ve done any better. It’s easy to criticize.

Those folks, they were doing their best. They were trying to step away from our culture. They didn’t use English, they didn’t even use mathematical symbols. They understood that those things are arbitrary, and they were reaching for something they hoped was going to be universal. But in the end, nothing can be universal because language is always symbols, and the choice of those symbols is arbitrary and cultural. It’s impossible to choose a symbol that can only be interpreted in one way.

Fundamentally, the book is trying to poke at our assumptions. It’s so inspiring to me that the history of physics is littered with times when we have had to abandon an assumption that we clung to desperately, until we were shown otherwise with enough data. So we’ve got to be really open-minded about whether these assumptions hold true, whether it’s required to do science, to be technological, or whether there is even a single explanation for reality. We could be very well surprised by what we discover.

Ars Technica: It’s often assumed that math and physics are the closest thing we have to a universal language. You challenge that assumption, probing such questions as “what does it even mean to ‘count’”?

Daniel Whiteson: At an initial glance, you’re like, well, of course mathematics is required, and of course numbers are universal. But then you dig into it and you start to realize there are fuzzy issues here. So many of the assumptions that underlie our interpretation of what we learned about physics are that way. I had this experience that’s probably very common among physics undergrads in quantum mechanics, learning about those calculations where you see nine decimal places in the theory and nine decimal places in the experiment, and you go, “Whoa, this isn’t just some calculational tool. This is how the universe decides what happens to a particle.”

I literally had that moment. I’m not a religious person, but it was almost spiritual. For many years, I believed that deeply, and I thought it was obvious. But to research this book, I read Science Without Numbers by Hartry Field. I was lucky—here at Irvine, we happen to have an amazing logic and philosophy of science department, and those folks really helped me digest [his ideas] and understand how you can pull yourself away from things like having a number line. It turns out you don’t need numbers; you can just think about relationships. It was really eye-opening, both how essential mathematics seems to human science and how obvious it is that we’re making a bunch of assumptions that we don’t know how to justify.

There are dotted lines humans have drawn because they make sense to us. You don’t have to go to plasma swirls and atmospheres to imagine a scenario where aliens might not have the same differentiation between their identities, me and you, here’s where I end, and here’s where you begin. That’s complicated for aliens that are plasma swirls, but also it’s not even very well-defined for us. How do I define the edge of my body? Is it where my skin ends? What about the dead skin, the hair, my personal space? There’s no obvious definition. We just have a cultural sense for “this is me, this is not me.” In the end, that’s a philosophical choice.

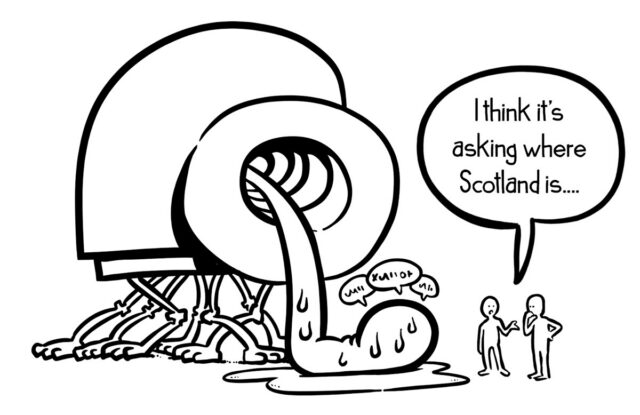

Credit: Andy Warner

Ars Technica: You raise another interesting question in the book: Would aliens even need physics theory or a deeper understanding of how the universe works? Perhaps they could invent, say, warp drive through trial and error. You suggest that our theory is more like a narrative framework. It’s the story we tell, and that is very much prone to bias.

Daniel Whiteson: Absolutely. And not just bias, but emotion and curiosity. We put energy into certain things because we think they’re important. Physicists spend our lives on this because we think, among the many things we could spend our time on, this is an important question. That’s an emotional choice. That’s a personal subjective thing.

Other people find my work dead boring and would hate to have my life, and I would feel the same way about theirs. And that’s awesome. I’m glad that not everybody wants to be a particle physicist or a biologist or an economist. We have a diversity of curiosity, which we all benefit from. People have an intuitive feel for certain things. There’s something in their minds that naturally understands how the system works and reflects it, and they probably can’t explain it. They might not be able to design a better car, but they can drive the heck out of it.

This is maybe the biggest stumbling block for people who are just starting to think about this for the first time. “Obviously aliens are scientific.” Well, how do we know? What do we mean by scientific? That concept has evolved over time, and is it really required? I felt that that was a big-picture thing that people could wrap their minds around but also a shock to the system. They were already a little bit off-kilter and might realize that some things they assumed must be true maybe not have to be.

Ars Technica: You cite the 2016 film Arrival as an example of first contact and the challenge of figuring out how to communicate with an alien species. They had to learn each other’s cultural context before they had any chance of figuring out what their respective symbols meant.

Daniel Whiteson: I think that is really crucial. Again, how you choose to represent your ideas is, in a sense, arbitrary. So if you’re on the other side of that, and you have to go from symbols to ideas, you have to know something about how they made those choices in order to reverse-engineer a message, in order to figure out what it means. How do you know if you’ve done it correctly? Say we get a message from aliens and we spend years of supercomputer time cranking on it. Something we rely on for decoding human messages is that you can tell when you’ve done it right because you have something that makes sense.

Credit: Andy Warner

How do we know when we’ve done that for an alien text? How do you know the difference between nonsense and things that don’t yet make sense to you? It’s essentially impossible. I spoke to some philosophers of language who convinced me that if we get a message from aliens, it might be literally impossible to decode it without their help, without their context. There aren’t enough examples of messages from aliens. We have the “Wow!” signal—who knows what that means? Maybe it’s a great example of getting a message and having no idea how to decode it.

As in many places in the book, I turned to human history because it’s the one example we have. I was shocked to discover how many human languages we haven’t decoded. Not to mention, we haven’t decoded whale. We know whales are talking to each other. Maybe they’re talking to us and we can’t decode it. The lesson, again and again, is culture.

With the Egyptians, the only reason we were able to decode hieroglyphics is because we had the Rosetta Stone, but that still took 20 years there. How does it take 20 years when you have examples and you know what it’s supposed to say? And the answer is that we made cultural assumptions. We assumed pictograms reflected the ideas in the pictures. If there’s a bird in it, it’s about birds. And we were just wrong. That’s maybe why we’ve been struggling with Etruscan and other languages we’ve never decoded.

Even when we do have a lot of culture in common, it’s very, very tricky. So the idea that we would get a message from space and have no cultural clues at all and somehow be able to decode it—I think that only works in the scenario where aliens have been listening to us for a long time and they’re essentially writing to us in something like our language. I’m a big fan of SETI. They host these conferences where they listen to philosophers and linguists and anthropologists. I don’t mean to say that they’ve thought too narrowly, but I think it’s not widely enough appreciated how difficult it is to decode another language with no culture in common.

Ars Technica: You devote a chapter to the possibility that aliens might be able to, say, “taste” electrons. That drives home your point that physiologically, they will probably be different, biologically they will be different, and their experiences are likely to be different. So their notion of culture will also be different.

Daniel Whiteson: Something I really wanted to get across was that perception determines your sense of intuition, which defines in many ways the answers you find acceptable. I read Ed Yong’s amazing book, An Immense World, about animal perception, the diversity of animal experience or animal interaction with the environment. What is it like to be an octopus with a distributed mind? What is it like to be a bird that senses magnetic fields? If you’re an alien and you have very different perceptions, you could also have a different intuitive language in which to understand the universe. What is a photon? Is it a particle? Is it a wave? Maybe we just struggle with the concept because our intuitive language is limited.

For an alien that can see photons in superposition, this is boring. They could be bored by things we’re fascinated by, or we could explain our theories to them and they could be unsatisfied because to them, it doesn’t translate into their intuitive language. So even though we’ve transcended our biological limitations in many ways, we can detect gravitational waves and infrared photons, we’re still, I think, shaped by those original biological senses that frame our experience, the models we build. What it’s like to be a human in the world could be very, very different from what it’s like to be an alien in the world.

Ars Technica: Your very last line reads, “Our theories may reveal the patterns of our thoughts as much as the patterns of nature.” Why did you choose to end your book on that note?

Daniel Whiteson: That’s a message to myself. When I started this journey, I thought physics is universal. That’s what makes it beautiful. That implies that if the aliens show up and they do physics in a very different way, it would be a crushing disappointment. Not only is what we’ve learned just another human science, but also it means maybe we can’t benefit from their work or we can’t have that fantasy of a galactic scientific conference. But that actually might be the best-case scenario.

I mean, the reason that you want to meet aliens is the reason you go traveling. You want to expand your horizons and learn new things. Imagine how boring it would be if you traveled around the world to some new country and they just had all the same food. It might be comforting in some way, but also boring. It’s so much more interesting to find out that they have spicy fish soup for breakfast. That’s the moment when you learn not just about what to have for breakfast but about yourself and your boundaries.

So if aliens show up and they’re so weirdly different in a way we can’t possibly imagine—that would be deeply revealing. It’ll give us a chance to separate the reality from the human lens. It’s not just questions of the universe. We are interesting, and we should learn about our own biases. I anticipate that when the aliens do come, their culture and their minds and their science will be so alien, it’ll be a real challenge to make any kind of connection. But if we do, I think we’ll learn a lot, not just about the universe but about ourselves.

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

What if the aliens come and we just can’t communicate? Read More »