This rare 11th-century Islamic astrolabe is one of the oldest yet discovered

An instrument from Verona —

“A powerful record of scientific exchange between Arabs, Jews, & Christians over 100s of years.”

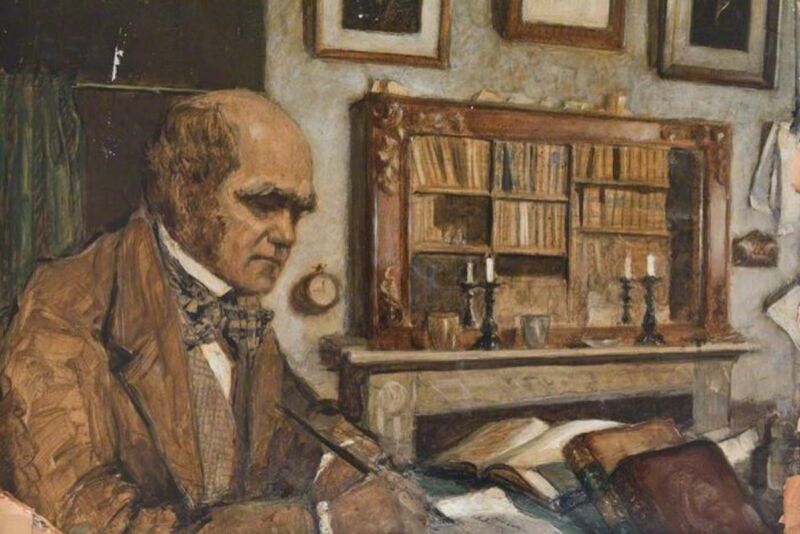

Enlarge / Close-up of the 11th-century Verona astrolabe showing Hebrew (top left) and Arabic inscriptions.

Federica Gigante

Cambridge University historian Federica Gigante is an expert on Islamic astrolabes. So naturally she was intrigued when the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo in Verona, Italy, uploaded an image of just such an astrolabe to its website. The museum thought it might be a fake, but when Gigante visited to see the astrolabe firsthand, she realized it was not only an authentic 11th-century instrument—one of the oldest yet discovered—it had engravings in both Arabic and Hebrew.

“This isn’t just an incredibly rare object. It’s a powerful record of scientific exchange between Arabs, Jews, and Christians over hundreds of years,” Gigante said. “The Verona astrolabe underwent many modifications, additions, and adaptations as it changed hands. At least three separate users felt the need to add translations and corrections to this object, two using Hebrew and one using a Western language.” She described her findings in a new paper published in the journal Nuncius.

As previously reported, astrolabes are actually very ancient instruments—possibly dating as far back as the second century BCE—for determining the time and position of the stars in the sky by measuring a celestial body’s altitude above the horizon. Before the emergence of the sextant, astrolabes were mostly used for astronomical and astrological studies, although they also proved useful for navigation on land, as well as for tracking the seasons, tide tables, and time of day. The latter was especially useful for religious functions, such as tracking daily Islamic prayer times, the direction of Mecca, or the feast of Ramadan, among others.

Navigating at sea on a pitching deck was a bit more problematic unless the waters were calm. The development of a mariner’s astrolabe—a simple ring marked in degrees for measuring celestial altitudes—helped solve that problem. It was eventually replaced by the invention of the sextant in the 18th century, which was much more precise for seafaring navigation. Mariners’ astrolabes are among the most prized artifacts recovered from shipwrecks; only 108 are currently cataloged worldwide. In 2019, researchers determined that a mariner’s astrolabe recovered from the wreck of one of Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama’s ships is now officially the oldest known such artifact. The so-called Sodré astrolabe was recovered from the wreck of the Esmeralda (part of da Gama’s armada) off the coast of Oman in 2014, along with around 2,800 other artifacts.

An astrolabe is typically composed of a disk (mater) engraved with graduations to mark hours and/or arc degrees. The mater holds one more engraved flat plate (tympans) to represent azimuth and altitude at specific latitudes. Above these pieces is a rotating framework called the rete that essentially serves as a star map, with one rotation being equivalent to one day. An alidade attached to the back could be rotated to help the user take the altitude of a sighted star. Engravings on the backs of the astrolabes varied but often depicted different kinds of scales.

-

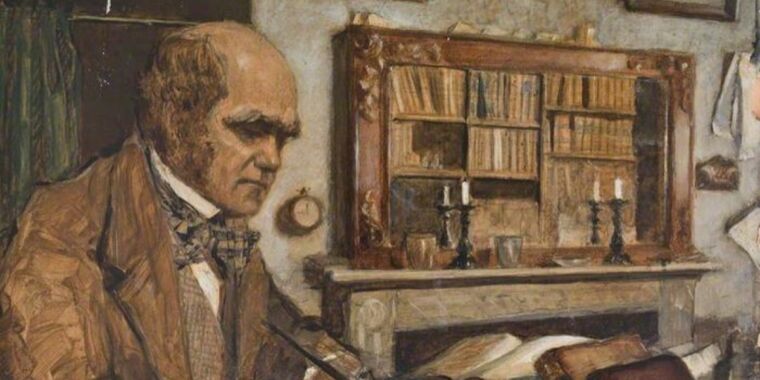

The Verona astrolabe, front and back views.

Federica Gigante

-

Close-up of the Verona astrolabe showing inscribed Hebrew, Arabic, and Western numerals.

Federica Gigante

-

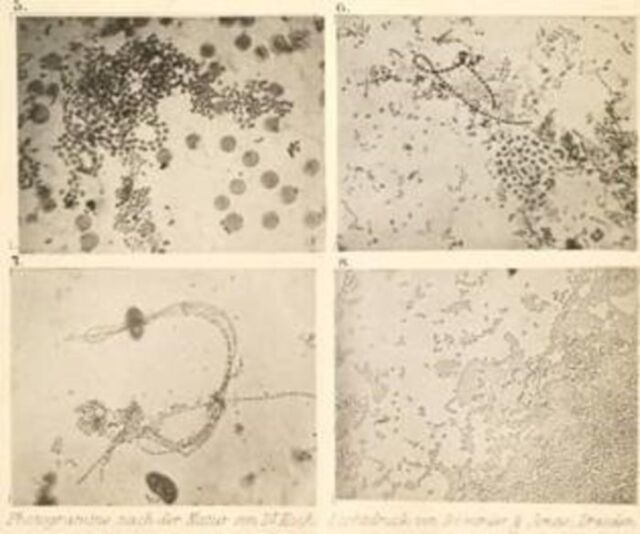

Dedication and signature: “For Isḥāq […], the work of Yūnus.”

Federica Gigante

-

Federica Gigante examining the Verona astrolabe.

Federica Candelato

The Verona astrolabe is meant for astronomical use, and while it has a mater, a rete, and two plates (one of which is a later replacement), it is missing the alidade. It’s also undated, according to Gigante, but she was able to estimate a likely date based on the instrument’s design, construction, and calligraphy. She concluded it was Andalusian, dating back to the 11th century when the region was a Muslim-ruled area of Spain.

For instance, one side of the original plate bears an Arabic inscription “for the latitude of Cordoba, 38° 30′,” and another Arabic inscription on the other side reads “for the latitude of Toledo, 40°.” The second plate (added at some later date) was for North African latitudes, so at some point, the astrolabe might have found its way to Morocco or Egypt. There are engraved lines from Muslim prayers, indicating it was probably originally used for daily prayers.

There is also a signature on the back in Arabic script: “for Isḥāq […]/the work of Yūnus.” Gigante believes this was added by a later owner. Since the two names translate to Isaac and Jonah, respectively, in English, it’s possible that a later owner was an Arab-speaking member of a Sephardi Jewish community. In addition to the Arabic script, Gigante noticed later Hebrew inscriptions translating the Arabic names for certain astrological signs, in keeping with the earliest surviving treatise in Hebrew on astrolabes, written by Abraham Ibn Ezra in Verona in 1146.

“These Hebrew additions and translations suggest that at a certain point the object left Spain or North Africa and circulated amongst the Jewish diaspora community in Italy, where Arabic was not understood, and Hebrew was used instead,” said Gigante. “This object is Islamic, Jewish, and European, they can’t be separated.”

Nuncius, 2024. DOI: 10.1163/18253911-bja10095 (About DOIs).

This rare 11th-century Islamic astrolabe is one of the oldest yet discovered Read More »