RAM shortage chaos expands to GPUs, high-capacity SSDs, and even hard drives

Big Tech’s AI-fueled memory shortage is set to be the PC industry’s defining story for 2026 and beyond. Standalone, direct-to-consumer RAM kits were some of the first products to feel the bite, with prices spiking by 300 or 400 percent by the end of 2025; prices for SSDs had also increased noticeably, albeit more modestly.

The rest of 2026 is going to be all about where, how, and to what extent those price spikes flow downstream into computers, phones, and other components that use RAM and NAND chips—areas where the existing supply of products and longer-term supply contracts negotiated by big companies have helped keep prices from surging too noticeably so far.

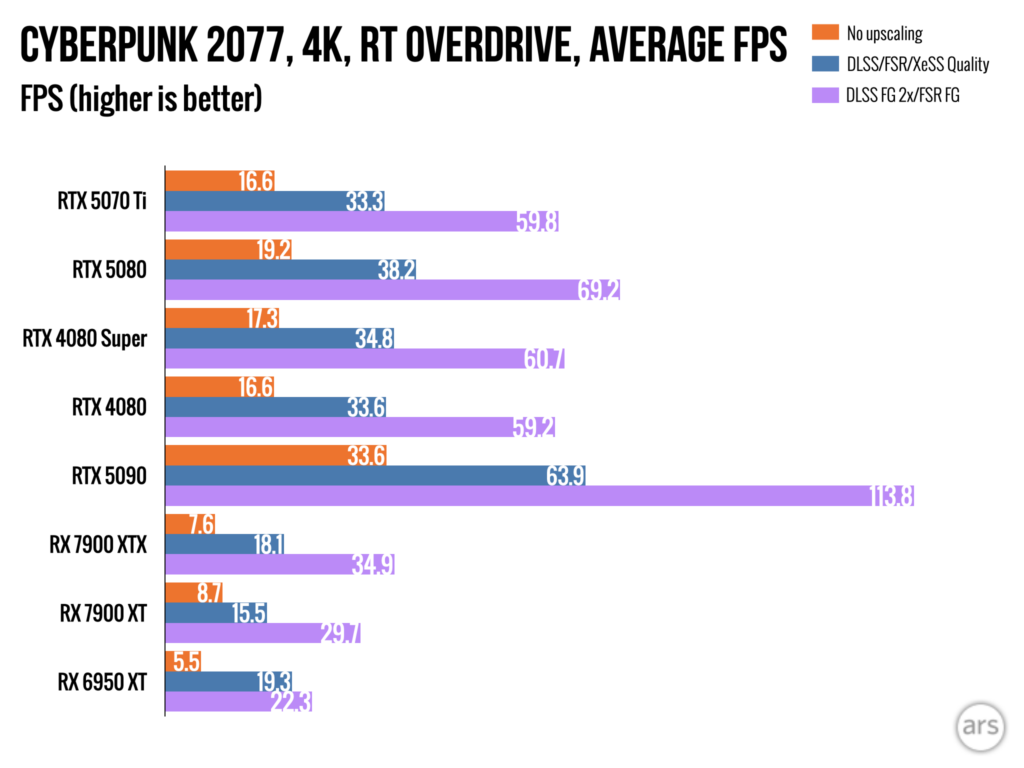

This week, we’re seeing signs that the RAM crunch is starting to affect the GPU market—Asus made some waves when it inadvertently announced that it was discontinuing its GeForce RTX 5070 Ti.

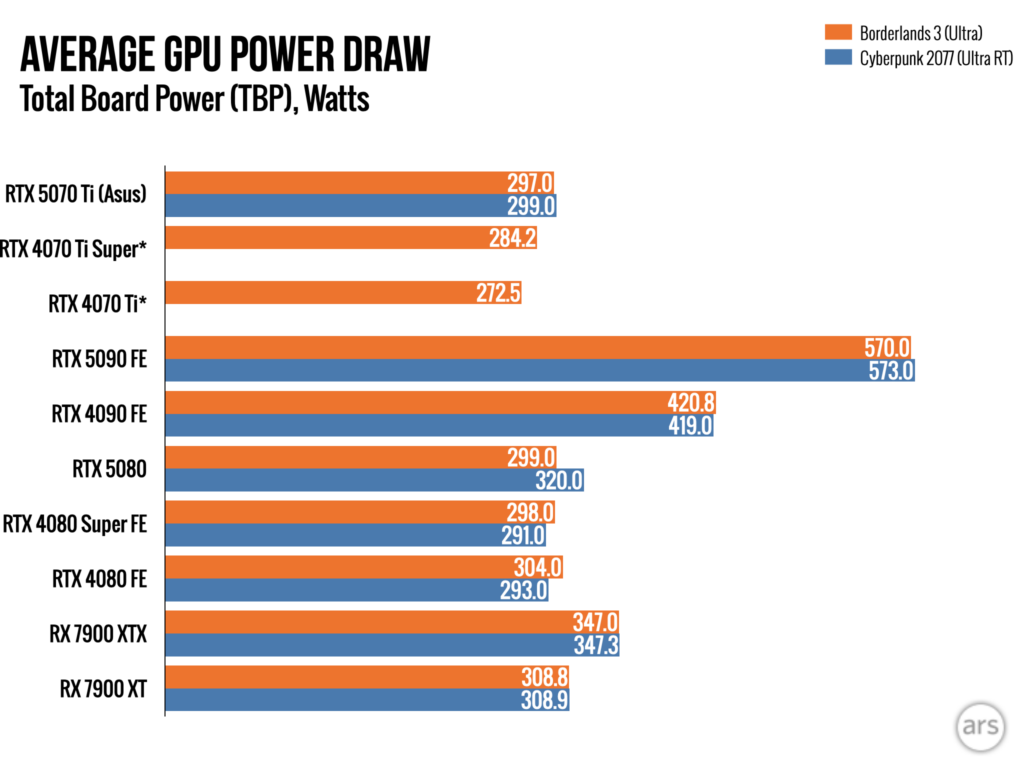

Though the company has since tried to walk this announcement back, if you’re a GPU manufacturer, there’s a strong argument for either discontinuing this model or de-prioritizing it in favor of other GPUs. The 5070 Ti uses 16GB of GDDR7, plus a partially disabled version of Nvidia’s GB203 GPU silicon. This is the same chip and the same amount of RAM used in the higher-end RTX 5080—the thinking goes, why continue to build a graphics card with an MSRP of $749 when the same basic parts could go to a card with a $999 MSRP instead?

Whether Asus or any other company is canceling production or not, you can see why GPU makers would be tempted by the argument: Street prices for the RTX 5070 Ti models start in the $1,050 to $1,100 range on Newegg right now, where RTX 5080 cards start in the $1,500 to $1,600 range. Though 5080 models may need more robust boards, heatsinks, and other components than a 5070 Ti, if you’re just trying to maximize the profit-per-GPU you can get for the same amount of RAM, it makes sense to shift allocation to the more expensive cards.

RAM shortage chaos expands to GPUs, high-capacity SSDs, and even hard drives Read More »