Metropolis 1998 lets you design every building in an isometric, pixel-art city

Have you ever really thought about living rooms? —

Devs cite Rollercoaster Tycoon, Dwarf Fortress, and, yes, SimCity as inspiration.

Enlarge / There is something so wonderfully obscene about having a town with hundreds of people living their lives, running into conflict, hoping for better, and your omnipotent self is stuck on which bookcase best fits this living room corner.

YesBox

Naming a game must be incredibly hard. How many more Dark Fallen Journeys and Noun: Verb of the Noun games can fit into the market? And yet certain games just appear with a near-perfect, properly descriptive label.

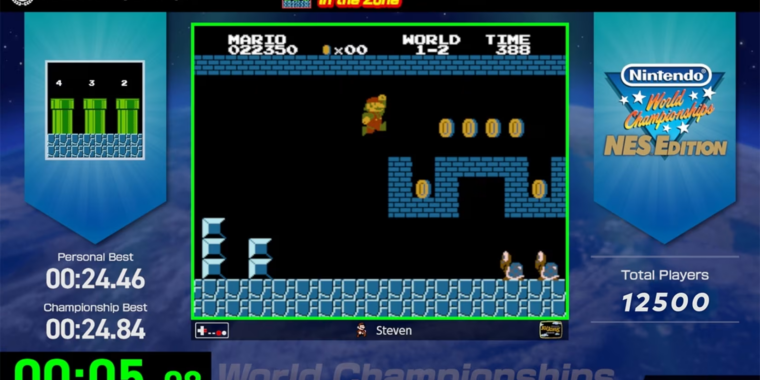

Metropolis 1998 is just such a game, telling you what you’ll be doing, how it will look and feel, and what era it harkens back to. You can verify this with its “pre-alpha” demo on Steam and Itch.io. There’s plenty more to come, but what is already in place is impressive. And it’s simply pleasant to play, especially if you’re the type who wants to make something entirely yours. Not just “put the park inside the commercial district,” but The Sims-style “choose which wood color for the dining room table in a living room you framed up yourself.”

You start out in a big field with no features (yet) and the sounds of birds chirping. Once you lay down a road, you can add things at a few different levels. You can, SimCity-style, simply plot out colored zones and let the people figure it out themselves. You can add pre-made buildings individually. Or you can really get in there, spacing out individual rooms, choosing the doors and windows and objects inside, and realizing how hard it is to shape multi-floor houses so the roof doesn’t look grotesque. You can save the filled-out house for later reuse or just hold on to its core aspects as a blueprint.

-

The author is quite proud of his first real home build, though he now realizes that living rooms have a big empty space, and it’s up to us to figure out just how empty it should remain.

Kevin Purdy

-

It takes a bit to get used to it, but the detailed building designer is full of wonderful little pieces, like this classic speaker cabinet with the black and red wire clips visible on the back.

The game is still early in development, so its mechanics are not introduced in tutorials, and the interface requires a lot of clicking, reading, and wondering. I got a reasonable feel for it after about 30 minutes of tentative placing and bulldoze-deletion. You can save your game and come back to it, though the developers note that your saves may not transfer to future versions. You’re putting your time in now, so you’ll be ready to start fresh when the game releases into early access (“ETA sometime between Q4 2024 and Q2 2025”). If you’re into this kind of fine-toothed builder, a fresh start is a gift, anyway.

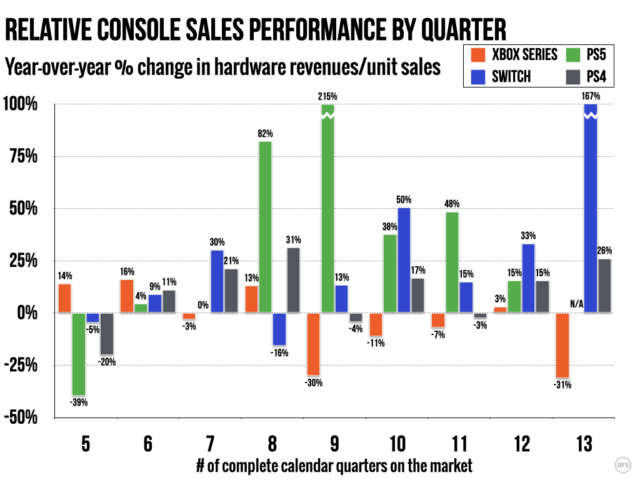

Developer video describing how the Metropolis 1998 algorithm scales to track hundreds of thousands of working objects.

Bank robberies and zombie scenarios ahead (maybe)

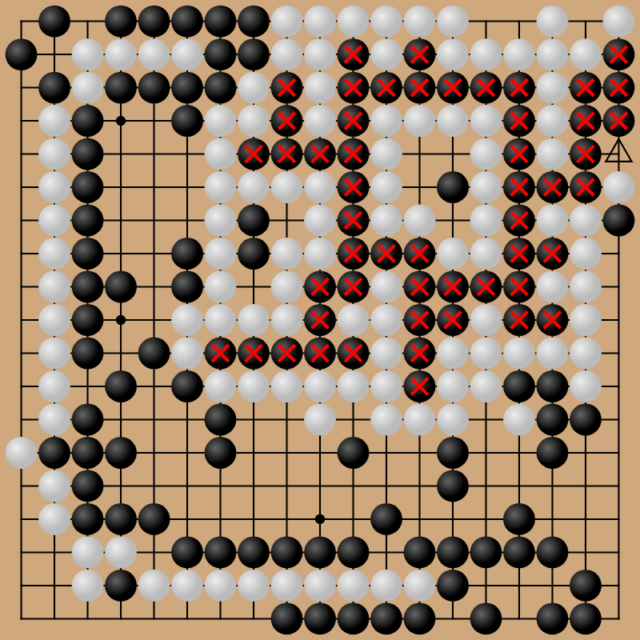

What will the game look like when it’s finished? Developer YesBox has a detailed roadmap and a blog detailing how it’s going. The very small team, seemingly a solo developer with art help from two others, started off in December 2021 and has achieved quite a lot, including an algorithm seemingly ready to handle big populations. A key promise of the game is that you won’t just lay down zones and wait for people and problems to show up. You will lay down specific buildings, like hospitals and police stations, and manage the usual concerns of traffic, zone demand, and the like. The “Post-1.0 Aspirations” hint at the game’s direction: “Visible Crime (e.g., watch a bank robbery),” “Zombie Mode (your police vs. your zombie population),” and “Live in your own city” in a “Sims-like mode” imply more of a toybox mentality than a “Highly realistic ports and infrastructure” ambition.

-

There’s a top-down mode in the game, useful for when you’re looking more into data than design.

YesBox

-

With enough time and object rotation, streets look like they can get mighty pretty.

YesBox

-

Screenshots suggest cities more complex than suburban plots are possible in Metropolis 1998.

YesBox

-

Letting your imagination go wild with the building designer can yield all kinds of city designs

YesBox

-

Check, check, check, check, this list of game inspirations works out, yep.

YesBox

Metropolis 1998 is not alone in seeking out city-builder fans living in the long wake of any proper SimCity release. But unlike games like Cities: Skylines 2, it’s not seeking the kind of mechanical complexity that would see it, say, figuring out eerily familiar housing cost crises. Building this kind of game is still fiendishly complex, of course. But how that complexity is presented to the player is something else.

The most interesting line in the roadmap is “player starts with land purchased from successful business exit.” I can’t help but think of Stardew Valley, which can also sprawl to ridiculous levels but has at its core the arc of a person who got tired of the rat race and inherited a farm. I’m looking forward to this invitingly retro and human-scale city-builder, with patience and respect for what seems like a massive developer undertaking.

Metropolis 1998 lets you design every building in an isometric, pixel-art city Read More »