No one loves President Trump more than FCC Chairman Brendan Carr

Trump’s biggest fan runs the FCC

Carr used to insist on FCC independence. Now he uses FCC to fight Trump’s battles.

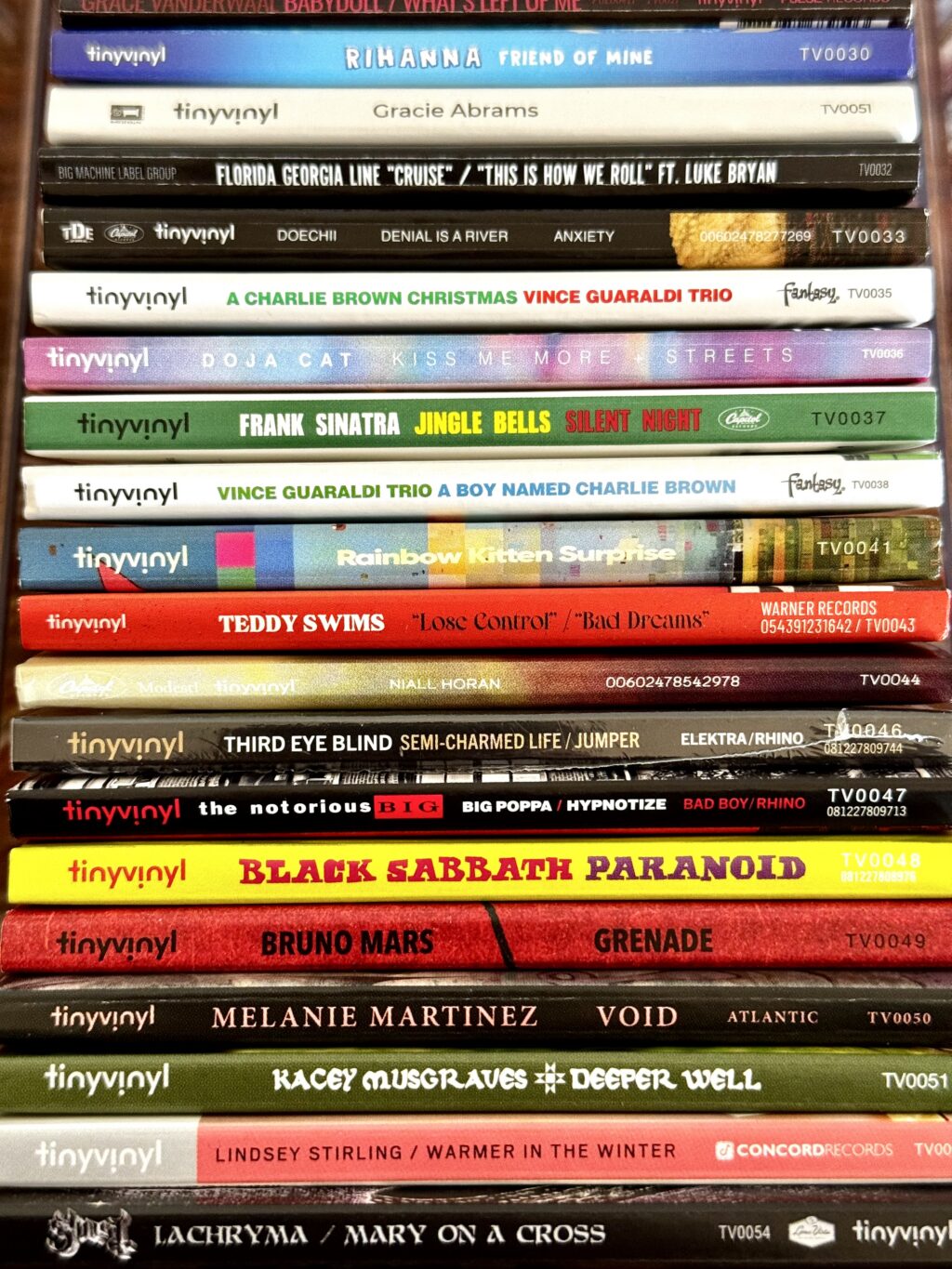

President-elect Donald Trump speaks to Brendan Carr, his intended pick for Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, as he attends a SpaceX Starship rocket launch on November 19, 2024 in Brownsville, Texas. Credit: Getty Images | Brandon Bell

Before he became chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, Brendan Carr seemed to be a big believer in the agency’s role as an independent branch of the federal government. According to the pre-2025 version of Brendan Carr, the White House interfered with the agency’s independence when a Democratic president publicly urged the FCC to adopt net neutrality rules.

When the Biden-era FCC reinstated Obama-era net neutrality rules in 2024, Carr alleged that President Biden “took the extraordinary step to pressure the FCC—an independent agency that is designed to operate outside undue political influence from the Executive Branch.” As evidence, Carr pointed to a 2021 executive order in which Biden called on agency heads to “consider using their authorities” for various types of pro-competitive policies, including the adoption of net neutrality rules.

Carr said that President Obama similarly “pressure[d] an independent agency into grabbing power that the Legislative Branch never said it had delegated.” Obama’s intrusion into this independence, according to Carr, came in November 2014 when the president released a two-minute video urging the agency to implement net neutrality rules and reclassify broadband providers as common carriers.

While the FCC was created as an independent agency, it isn’t apolitical. There are Republican and Democratic members, and by design, the president’s party has a majority. FCC policies change dramatically from one administration to the next.

But Carr couldn’t have been clearer about his belief that the president should not publicly urge the FCC to take specific actions. “The White House did not let the FCC chair do his job,” Carr said last year, referring to the events of 2014 and 2015 involving Obama and then-FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler. “The president intervened. He flipped him.”

But then Donald Trump won a second term in office and promoted Commissioner Carr to the position of FCC chairman in January 2025. A few weeks later, Trump issued an executive order declaring that historically independent agencies could no longer operate independently from the White House.

Carr’s devotion to President Trump

Trump has continued his longtime practice of publicly calling on FCC chairs to revoke broadcast licenses from news organizations that Trump dislikes. Former FCC chairs Jessica Rosenworcel and Ajit Pai rejected these calls when they led the agency. Carr has instead amplified Trump’s complaints and repeatedly threatened to revoke broadcast licenses through investigations into news distortion.

Carr, a longtime Trump supporter who sometimes wears a Trump-shaped lapel pin, wrote a Project 2025 chapter in 2023 describing how the FCC should be overhauled to achieve conservative priorities. It was never likely that he and Trump would differ much in their policy positions. But few, if any, leaders of historically independent agencies have aligned themselves with Trump as consistently and vocally as Carr has in his first year as FCC chairman.

Carr’s devotion to the president has been most obvious to the general public whenever he threatens broadcaster licenses. But Carr hardly seems independent of Trump when it comes to his other actions as head of the FCC. His press releases announcing various types of FCC decisions often praise Trump’s leadership and say the FCC is acting to advance a Trump priority.

“We are fully aligned with the agenda that President Trump is running,” Carr told The Wall Street Journal.

Far from insisting that the FCC make decisions independently, Carr has welcomed Trump’s direct orders. After Trump issued a December 11 executive order requiring the FCC to open a proceeding that could lead to preemption of state AI laws, Carr issued a statement saying that “the FCC welcomes President’s Trump’s direction.”

We emailed Carr in early December, requesting a phone interview or comments about whether he still believes the FCC should operate independently from the White House and did not receive a response. But on December 17, Carr confirmed during a Senate hearing that he no longer believes the FCC is independent from the White House.

“There’s been a sea change in the law since I wrote that sentence,” he said after being confronted with one of his previous statements describing the agency as independent. “The FCC is not an independent agency” because “the president can remove any member of the commission for any reason or no reason,” he said.

Wheeler, who is still active in tech and telecom policy at the Brookings Institution and Harvard Kennedy School, has watched the current FCC with dismay. “The FCC is a policy agency that exists in a political environment, and the Trump administration has turned it into a political agency existing in a policy environment,” Wheeler told Ars in a phone interview early this month.

Wheeler said he has “respect for Brendan, his brain, his political skills, his way of framing issues and expressing himself. I’m disappointed that he’s using them in the manner that he is, in just being a cipher for the MAGA agenda.”

Wheeler: Obama “never called me”

Congress created the FCC in 1934. As indications of its independence, the FCC has commissioners with specified tenures, a multimember structure, partisan balance, and adjudication authority. The agency can also issue regulations within limits set by Congress and courts.

US law lists 19 federal agencies, including the FCC, that are classified as “independent regulatory agencies.” The FCC’s independence was until recently acknowledged by the FCC itself, which said on its website that it is “an independent US government agency overseen by Congress.” Carr apparently wasn’t aware that the statement was still on the website until the December 17 Senate hearing. It was deleted quickly after Sen. Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.) asked Carr, “Is your website wrong, is your website lying?”

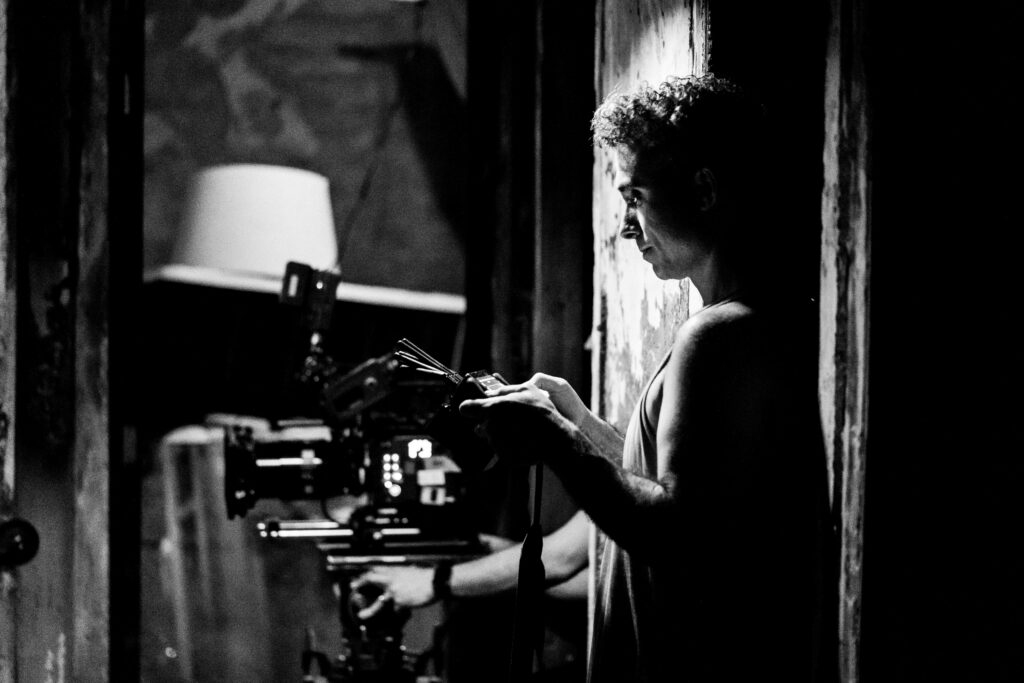

Then-Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler (L) and FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai talk before testifying to the House Judiciary Committee on March 25, 2015, in Washington, DC. Credit: Getty Images | Chip Somodevilla

“Congress said, ‘you should be an independent agency,’ and Trump steps up and says, ‘no, you’re not an independent agency,’” Wheeler said. “Brendan apparently is going along with that if you judge from his trips to Mar-a-Lago and elsewhere.” Wheeler is also disappointed that after Trump’s executive order, “the Congress rolled over and just said, ‘oh, fine.’”

When Wheeler led a 2015 vote to implement net neutrality rules, Republicans in Congress claimed the agency was improperly influenced by Obama. “Five days of hearings under oath and an IG investigation that cleared me of wrongdoing,” Wheeler said, recalling the post-vote investigations by Congress and the FCC’s independent Inspector General’s office. “It was political. It was Republican-controlled committees who were looking for a reason to go after a Democratic-controlled FCC,” he said.

At the time, Wheeler told Congress there were “no secret instructions” from Obama. Wheeler said he treated Obama’s input “with respect” but also listened to “nearly four million Americans, who overwhelmingly spoke in favor of preserving a free and open Internet” in comments to the FCC.

Wheeler told Ars that during his term as FCC chairman, Obama “never called me.” Wheeler said that in his first week as chairman in 2013, “he said to me, ‘Tom, I will never call you. You’re an independent agency,’ and he was good to his word. Did he do a video? Yeah. Does he have a right to do a video? Of course.”

FCC decisions “coordinated through the White House”

FCC Commissioner Anna Gomez, the only Democrat on the FCC, said in a phone interview in early December that “it is appropriate for the president to have an opinion, even to put an opinion out there,” as Biden and Obama did on net neutrality. “The public statements are different than actions,” she said. “What we’re seeing now are direct actions to undermine our independence.”

Gomez said Trump’s frequent demands on the FCC to revoke broadcast licenses have a “more coercive effect” because of “the overall actions by this president to fire anyone that doesn’t do his will.” That includes Trump firing both Democrats on the Federal Trade Commission, another historically independent agency.

The Supreme Court has so far allowed the firing of former FTC Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter to stand while Slaughter’s lawsuit against Trump remains pending. At oral arguments, it appeared likely that the Supreme Court will rule that Trump can fire FTC commissioners.

At the December 17 Senate hearing, Carr cited the FTC case to support his view that the FCC isn’t independent. Carr said it used to be assumed that FCC commissioners would be protected from removal by the Supreme Court’s 1935 ruling in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, which unanimously held that the president can only remove FTC commissioners for inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.

The Communications Act was passed one year before Humphrey’s Executor and did not include explicit protection from removal, but “the theory had been that courts would read for-cause removal into the [Communications] statute and that was the basis for that viewpoint,” Carr said. “I think now it’s clear that’s not the case, so formally speaking the FCC isn’t independent because we don’t have that key piece, which is for-cause removal protection.” Carr said “the sine qua non of independence” is having protection from removal by the president.

Gomez has said she doesn’t know why Trump hasn’t fired her yet. “That erosion of our independence is negative for a variety of reasons,” Gomez said. “What worries me is that we will continue to see this White House pressure the FCC to favor or punish certain companies, to influence media ownership or media coverage, and to shape what information reaches the public.”

Gomez said the agency this year started sending decisions to the White House’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) for review before they are voted on. This practice is in line with one of the directives in the Trump executive order that declared independent agencies are no longer independent.

“We have a multi-member commission that makes these decisions, and somehow this is all getting coordinated through the White House before [the commissioners] vote on something. That is not independent,” Gomez said. While there were previously post-vote reviews, such as the standard reviews required under a 1980 law called the Paperwork Reduction Act, the OIRA process consists of “pre-clearance and approval of anything that we’re voting on. That is new,” Gomez said.

Gomez doesn’t know if those reviews have resulted in any significant changes to FCC actions before votes. “I’m not privy to that,” she said.

Carr heaps praise on Trump

Even before the Trump executive order that purported to eliminate the FCC’s independence, Carr attributed one of his first actions to an order from Trump. One day after the January 20 inauguration, Carr announced that he was ending the FCC’s promotion of DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) policies. The press release said the FCC action was taken “pursuant to” Trump’s day-one executive order on DEI.

“Today, pursuant to the policies stated in the Executive Order, FCC Chairman Brendan Carr announced that he is ending the FCC’s promotion of DEI,” the January 21 press release said. In the months since, Carr has repeatedly demanded that companies end internal DEI practices in exchange for FCC merger approvals.

Carr’s press releases announcing FCC decisions have continued to praise Trump for his leadership of the country. Instead of stating that the FCC makes decisions independently, without “undue political influence from the Executive Branch,” Carr’s press releases often specifically describe FCC decisions as advancing Trump’s agenda.

“This action follows President Trump’s leadership and the Trump Administration’s decision to usher in prosperity through deregulation,” one such Carr press release said while announcing the “Delete, Delete, Delete” plan to eliminate many of the agency’s regulations.

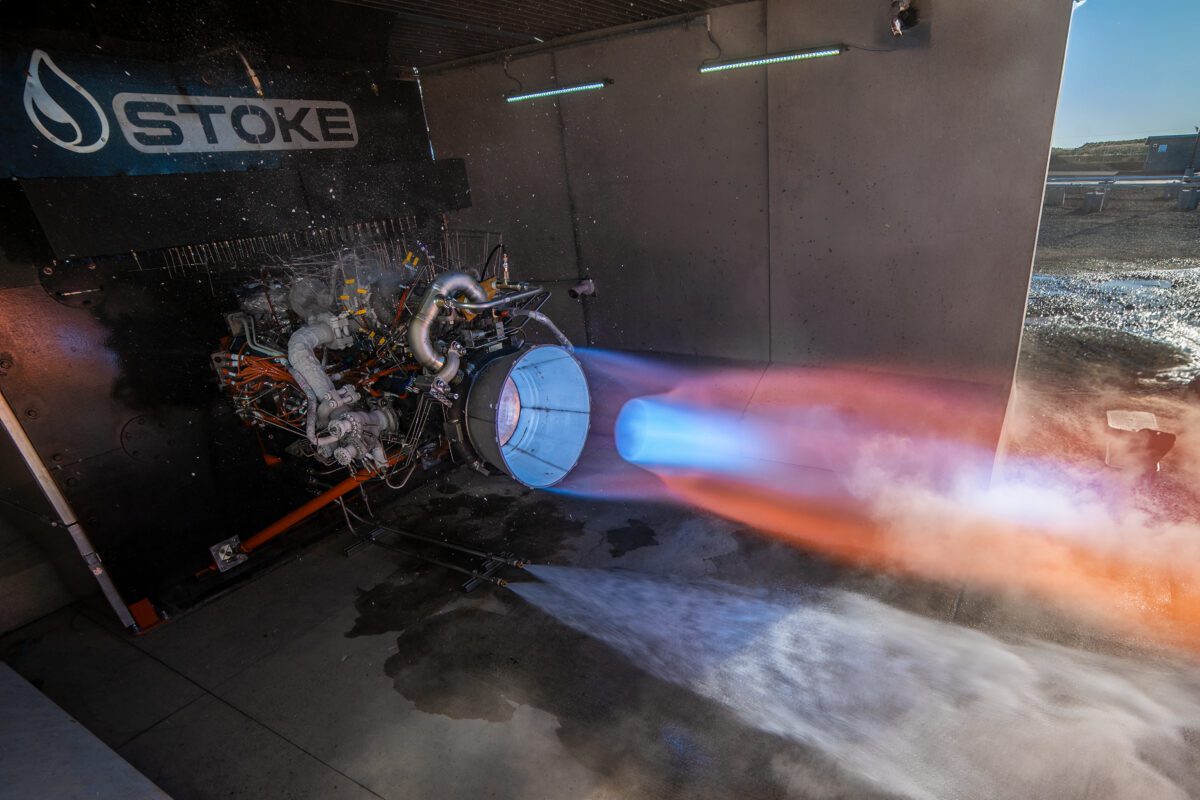

Carr makes statements praising Trump both when he announces decisions on politically charged topics and when he announces decisions on more routine matters handled by the FCC. “With President Trump’s leadership, America is entering a new Golden Age of innovation in space—one where US businesses are going to dominate,” Carr said in October to explain why he was making changes to space licensing and spectrum use rules.

Carr: “Trump is fundamentally reshaping the media landscape”

Of course, Carr’s most controversial initiative almost certainly wouldn’t exist if not for President Trump’s frequent demands that news outlets be punished for supposed bias. Carr’s approach differs markedly from the two previous FCC chairs—Rosenworcel, a Democrat, and Pai, a Republican—who said the FCC should avoid regulating broadcast content in order to uphold the free speech protections in the First Amendment.

By contrast, Carr has repeatedly threatened to enforce the FCC’s previously dormant news distortion policy against broadcasters by taking away station licenses. Carr has made it clear in numerous public statements that he’s taking his cue from Trump.

“For years, people cowed down to the executives behind these companies based in Hollywood and New York, and they just accepted that these national broadcasters could dictate how people think about topics, that they could set the narrative for the country—and President Trump fundamentally rejected it,” Carr told Newsmax in July. “He smashed the facade that these are gatekeepers that can determine what people think. Everything we’re seeing right now flows from that decision by President Trump, and he’s winning. PBS has been defunded. NPR has been defunded. CBS is committing to restoring fact-based journalism… President Trump stood up to these legacy media gatekeepers, and now their business models are falling apart.”

Carr made that statement after approving CBS owner Paramount’s $8 billion merger with Skydance on the condition that the company install an ombudsman, which Carr described as a “bias monitor.” Carr only approved the transaction once Paramount reached a $16 million settlement with Trump, who sued the company because he didn’t like how CBS edited a pre-election interview with Kamala Harris.

While the FCC order claimed the merger approval and ombudsman condition were unrelated to the Trump lawsuit, Carr repeatedly credited Trump for forcing changes at news broadcasters when giving interviews about that and other FCC actions. Carr uses similar language throughout these various interviews, saying that Trump “ran directly at” news organizations during his election campaign and “smashed the facade.”

“President Trump is fundamentally reshaping the media landscape,” he said in one interview. He said in another that “President Trump ran directly at the legacy mainstream media, and he smashed a facade that they’re the gatekeepers of truth.”

Ted Cruz and Rand Paul say Carr went too far

When Carr threatened the licenses of ABC stations over comments made by comedian Jimmy Kimmel, even some prominent Republicans said he went too far. “Brendan Carr has got no business weighing in on this,” Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) said, calling Carr’s statement that ABC owner Disney must take action against Kimmel “absolutely inappropriate.”

Carr unconvincingly claimed that he never threatened ABC station licenses, even though he specifically said stations that continued to air Kimmel’s show were “running the possibility of fines or license revocations.” One person who didn’t buy Carr’s explanation was Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas). The senator from Texas didn’t like it when Carr told ABC and Disney that “we can do this the easy way or the hard way.”

Cruz said Carr’s “easy way or the hard way” statement was an obvious threat and “right outta Goodfellas.” Cruz would later say at the December 17 hearing that Congress should restrict the FCC’s power to intimidate news broadcasters. Cruz said, “the public interest standard and its wretched offspring, like the news distortion rule, have outlived whatever utility they once had and it is long past time for Congress to pass reforms.”

Even after bipartisan criticism, Carr refused to end his news distortion investigations. “How about no,” Carr wrote in November. “On my watch, the FCC will continue to hold broadcasters accountable to their public interest obligations.”

Wheeler: “Brendan needs to man up and own his decisions”

One of Carr’s defenses of his news distortion probes is that Rosenworcel’s FCC kept an advocacy group’s petition to deny a Fox station license renewal on the docket for over a year instead of dismissing it outright. Rosenworcel ultimately dismissed the petition, which alleged that Fox willfully distorted news with false reports of fraud in the 2020 election that Trump lost.

The petition pointed out that a judge presiding over a Dominion Voting Systems defamation lawsuit against Fox found that Fox News aired false statements about Dominion. Fox subsequently agreed to a $788 million settlement.

Rosenworcel simultaneously dismissed the Fox petition and three complaints alleging anti-Trump or anti-conservative bias by ABC, CBS, and NBC, saying that all four requests “seek to weaponize the licensing authority of the FCC in a way that is fundamentally at odds with the First Amendment.” Carr reinstated the conservative complaints against ABC, CBS, and NBC, but not the one against Fox.

Carr defended his actions by saying the Biden administration “weaponized our country’s communications laws,” and that his own FCC simply “put the CBS complaint on the same procedural footing that the Biden FCC determined it should apply to the Fox complaint.”

Wheeler said Carr shouldn’t blame his actions on his predecessors. “I own my decisions,” Wheeler said. “I think that Brendan needs to man up and own his decisions and quit this ‘what about.’ He’s always out there saying, ‘Well, what about what Jessica did or what about what Wheeler did?’… Is that the best he can do? I mean, take responsibility for your decisions and go forward.”

Gomez: “This administration has weaponized the FCC”

Gomez said that when Congress created the FCC’s predecessor, the Federal Radio Commission, “it decided that it was too dangerous to have one person beholden to the president, to the whims of one person, in charge of the most important communication medium of the time, which was radio. So Congress decided, after deliberating it, to create a multi-member independent agency. And when it created the FCC, it did exactly that as well.”

Gomez continued: “[I]t has been important throughout history to keep that independence from political pressure. And what you’re seeing in this administration is completely different. This administration has weaponized the FCC in order to retaliate, pressure, and intimidate companies into doing its will.”

FCC Commissioner Anna Gomez during a Bloomberg Television interview in New York, on Friday, Sept. 19, 2025. Credit: Getty Images | Bloomberg

Gomez said the weaponization is evident in how the FCC handles mergers and other transactions in which the agency decides whether to approve the transfer of licenses from one company to another. Carr has explicitly demanded that companies eliminate their DEI policies in exchange for approvals.

“This FCC has said that it will not approve a single license transfer for companies that have diversity, equity, and inclusion policies,” Gomez said, noting that the FCC’s anti-DEI policies were implemented right after Trump’s anti-DEI executive order. “That is why you see the FCC granting transfers of control immediately after getting letters from companies agreeing to drop their diversity, equity, and inclusion policies.”

Companies such as AT&T, T-Mobile, Verizon, and Skydance have ended DEI programs to gain Carr’s approval for transactions.

“We also saw that weaponization of the licensing authority with regard to the [FCC] pressuring EchoStar to give up its licenses,” Gomez said. “And that was done purposefully in order to ensure that other parties could get ahold of EchoStar’s licenses for spectrum.”

Trump intervened in EchoStar battle

SpaceX and AT&T struck deals to buy EchoStar spectrum licenses after Carr threatened to revoke the licenses. Trump intervened after Carr’s threat, as Bloomberg reported that Trump called Carr and summoned him to a White House meeting with EchoStar President Charlie Ergen and urged them to make a deal.

Carr’s pressuring of EchoStar was criticized by the Free State Foundation, a free-market group that usually supports Republican priorities at the FCC.

“Rescission of deadline extension orders granted months earlier undoubtedly creates a type of regulatory uncertainty,” the foundation said in reference to the FCC’s investigation into EchoStar. “Arbitrary and unforeseen” changes to rules or agency actions create instability in the market for wireless broadband deployment, it said.

Gomez said the FCC’s “authority rests on technical expertise, evidence, and the public record. When our agency’s decisions are insulated from partisan pressure, the public can trust the outcomes are driven by facts rather than politics.” She said it is also “important to maintain our global credibility because we have been viewed as a model for transparent, rule-based telecommunications regulation.”

Gomez, a telecommunications attorney, has worked in various private-sector and government roles over the past 30 years, including as deputy chief of the FCC International Bureau and senior legal adviser to then-FCC Chairman William Kennard during the Clinton administration. Prior to Biden’s nomination for her to serve as an FCC commissioner in 2023, she was at the US State Department as senior adviser for International Information and Communications Policy.

Executive order required review of FCC actions

Gomez said the FCC submitting decisions to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs before they’re voted on is a big change for an independent agency. Gomez said she’s deeply familiar with the OIRA process because of her previous work at the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), an executive branch agency that advises the president on telecom policy. She was the NTIA deputy administrator from 2009 to 2013.

The Trump executive order that purports to eliminate agency independence states that “all executive departments and agencies, including so-called independent agencies, shall submit for review all proposed and final significant regulatory actions to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) within the Executive Office of the President before publication in the Federal Register.”

In a section titled “OIRA Review of Agency Regulations,” the Trump executive order amends a definition of agency that was previously included in Section 3(b) of a 1993 executive order on regulatory reviews. The specified section in that Clinton executive order defined agency as “any authority of the United States that is an ‘agency’ under 44 U.S.C. 3502(1), other than those considered to be independent regulatory agencies.” This carveout excluded independent agencies like the FCC from the requirement to submit draft regulatory actions for review.

The definition of “agency” in Trump’s executive order removes the language that excluded all independent regulatory agencies from OIRA requirements but includes a carveout for the Federal Reserve. Trump’s order also added the Federal Election Commission to the roster of agencies whose actions require OIRA review of significant actions, such as rulemakings.

While Gomez objects to the pre-clearance requirement, she noted that there are proper ways in which the FCC coordinates with executive branch agencies. For example, the FCC has a memorandum of understanding with the NTIA on how to coordinate spectrum management actions to prevent interference with federal systems that rely on specific radio frequencies.

“Another good use of coordination is in security, for example, when we coordinate with the security agencies to make sure that we are taking national security into consideration with our actions,” she said. “Our statute requires us to coordinate with the State Department and the Department of Justice… and that’s important to do in advance, and it’s good government.”

It’s also not uncommon for the FCC to receive advice from the current president’s administration through the NTIA, which expresses the executive branch’s views on telecom-policy matters in filings submitted in the public record. Those dockets attract filings from government agencies, companies, industry trade groups, advocacy groups, and anyone else who is interested in filing a comment, and the FCC takes the input into account before making decisions.

“What is improper,” Gomez said, “is when our decisions are being directed by this administration and impeding us from making our independent, expert-based judgment of how to manage resources and act in the public interest.”

Pai defied Trump, insisted on FCC independence

Carr was hired as a legal adviser by then-Commissioner Pai in 2014 and was briefly the FCC’s general counsel during Pai’s first year as chair in 2017. Carr became an FCC commissioner in August 2017 after a nomination by President Trump.

Carr and Pai have seemingly agreed on nearly everything to do with the FCC, with the most obvious exception being the regulation of broadcast media content. “I believe in the First Amendment,” Pai said in 2017, six days after Trump called for NBC license revocations. “The FCC under my leadership will stand for the First Amendment. And under the law, the FCC does not have the authority to revoke a license of a broadcast station based on the content of a particular newscast.”

In a January 2021 speech during his last week as FCC chairman, Pai discussed how he led a 2018 vote against Sinclair Broadcast Group’s proposed acquisition of Tribune Media Company because it would violate station ownership limits. Carr joined Pai in the unanimous vote.

“Sinclair is widely perceived to be a right-leaning broadcaster,” Pai said in the speech delivered at the American Enterprise Institute. “And the perception is probably accurate, just as it is probably accurate to say that many of our nation’s broadcast networks lean to the left. But the last time I checked, the First Amendment still applies to broadcasters, which means Sinclair’s perceived political views and the content of its newscasts should be entirely irrelevant to the FCC’s decision-making process.”

Trump didn’t like Pai’s rejection of the Sinclair deal. The president tweeted in July 2018, “So sad and unfair that the FCC wouldn’t approve the Sinclair Broadcast merger with Tribune. This would have been a great and much needed Conservative voice for and of the People. Liberal Fake News NBC and Comcast gets approved, much bigger, but not Sinclair. Disgraceful!”

Reflecting on this incident and other Trump comments about the Sinclair rejection in his January 2021 speech, Pai said, “in terms of powerful opponents in Washington, it’s hard to top the president.” Pai told the audience “that you don’t demonstrate the FCC’s independence by saying you’re independent. You do it by acting independently… This decision may have won me few friends, but I’m proud I lived up to my oath and preserved the agency’s independence.”

It’s no secret

Wheeler and Pai often clashed over policy differences when they served on the commission together. Pai even accused Wheeler of taking orders from Obama on net neutrality. But Pai’s exit speech made a positive impression on Wheeler.

“I seem to recall that Pai at the end of his term made a speech in which he talked about some of the proudest things he had done was maintaining the independence of the agency and protecting the First Amendment speech rights of the people,” Wheeler said.

While federal agency operations can change in ways that aren’t readily visible to the public, the changes to agency independence in Trump’s second term haven’t been hidden. “One thing about this is so much is out in the open, which I think is an effort to normalize it,” Gomez said. “And we have to resist it.”

Gomez knows she might not be able to serve out her entire term given that Trump fired Democrats from the FTC. The risk would be particularly high if the Supreme Court rules in Trump’s favor in the case filed by Slaughter. While the Senate has the authority to confirm or deny presidential nominations to the FCC and FTC, a Trump victory in the FTC case would give the president more power to dictate the membership of independent agencies.

“I don’t know why,” Gomez said when asked if she knows why Trump hasn’t fired her yet. “I don’t want to speculate. We’ll find out, I guess. But I’m focused on doing my work, and every day that I can continue to do my work and to speak out on behalf of consumers and the First Amendment is a good day.”

No one loves President Trump more than FCC Chairman Brendan Carr Read More »