How Eye Tracking Contributes to XR Analytics and Experience

Near-to-eye displays offer powerful new ways to understand what the wearer is doing – and maybe even thinking. Right now, the use of XR analytics like eye tracking is largely limited to enterprise including use cases like education and assessment, though eye tracking also enables new input modes and display improvements.

To learn more about the present and potential future of this technology, ARPost spoke with hardware manufacturer Lumus and XR analytics specialists Cognitive3D.

Why Do We Need XR Analytics?

XR analytics can be broken down generally into learning about an experience and learning about the person in that experience.

Learning About Experiences

Learning about an experience is important for people building XR applications – both in terms of building applications that people will want to use, and in building applications that people will be able to use.

“The stakes are much higher in creating high-quality content,” Cognitive3D founder and CEO Tony Bevilacqua said in an interview with ARPost. “That means creating something that’s comfortable, that’s not going to make you sick, that’s going to be accessible and well-received.”

This kind of thing is important for anyone building anything, but it is crucial for people building in XR, according to Bevilacqua. When a gamer experiences a usability problem in a console game or mobile app, they’re likely to blame that specific game or app and move onto a different one. However, XR is still new enough that people aren’t always so understanding.

“A bad experience can create attrition not just for an app, but for the platform itself,” said Bevilacqua. “That headset might go back into the box and stay there.”

Of course, developers are also interested in “success metrics” for their experiences. This is an issue of particular importance for people building XR experiences as part of advertising and marketing campaigns where traditional metrics from web and mobile experiences aren’t as useful.

“We all kind of know that opening an app and how much time people spent, those are very surface-level metrics,” said Bevilacqua. For XR, it’s more important to understand participation – and that means deeper analytical tools.

Learning About People

In other use cases, the people interacting with an experience are the subject that the XR analytics are most interested in. In these situations, Bevilacqua describes “the headset as a vehicle for data collection.” Examples include academic research, assessing skills and competency, and consumer research.

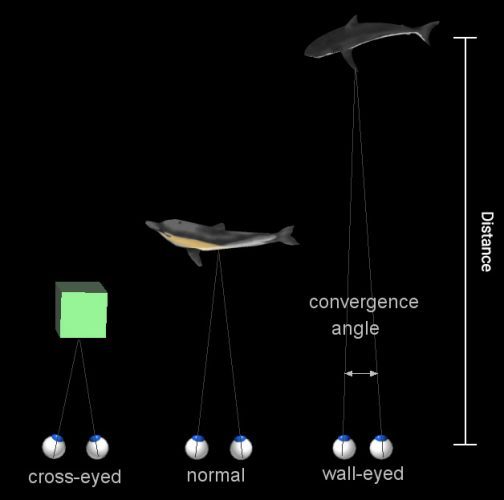

Competency assessment and consumer research might involve digital twins that the individual interacts with in VR. How efficiently can they perform a task? What do they think about a virtual preproduction model of a car? What products draw their eyes in a virtual supermarket?

“We focus more on non-consumer-focused use cases like focus groups,” said Bevilacqua. “We try to build off of the characteristics that make VR unique.”

At least part of the reason for this is that a lot of XR devices still don’t have the hardware required for XR analytics, like eye tracking capabilities.

Building Hardware for Eye Tracking

David Goldman is the Vice President of AR Optics at Lumus. The company is primarily focused on making displays but, as a components manufacturer, they have to make parts that work with other customer requirements – including eye tracking. The company even has a few patents on its own approach to it.

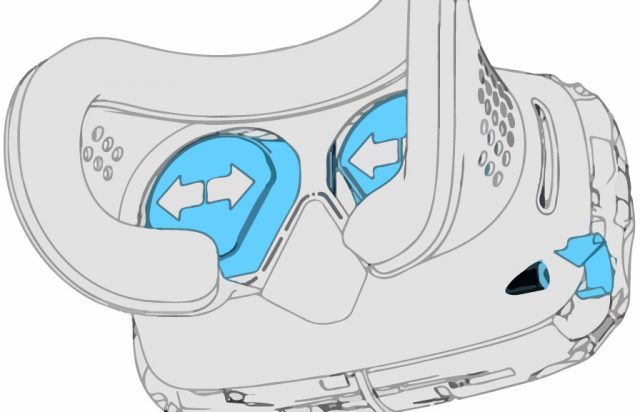

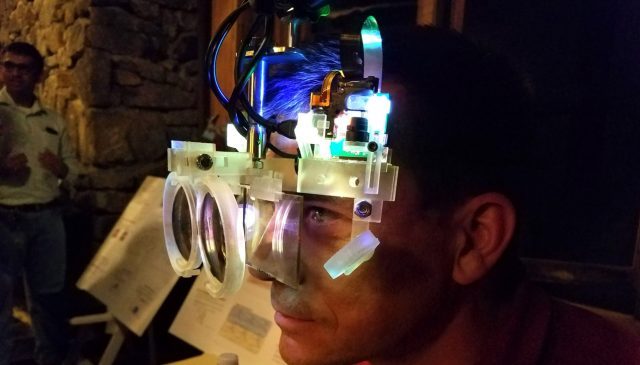

According to Goldman, traditional approaches to eye tracking involve cameras and infrared lights inside of the headset. The invisible light reflects off of the eye and is captured by the camera. Those lights and cameras add some cost but, more importantly, they take up “valuable real estate, from an aesthetic perspective.”

The patented Lumus system uses the waveguide itself as the light source because waveguides already require projecting light. This light reflects off of the eye, so all that is required is an additional inside camera, which is a lot more affordable in terms of cost and space. However, high standards for emerging experiences plays a role here too.

“When you’re a company trying to introduce a whole new product, you’re trying to shave pennies off of the dollar on everything,” said Goldman. “Looking at the bill of materials, it’s unlikely to make a first generation.”

Though, more and more devices coming to market do include this hardware – including consumer devices. Why? In part because the hardware enables a lot more than just XR analytics.

Enabling New Kinds of Interactions

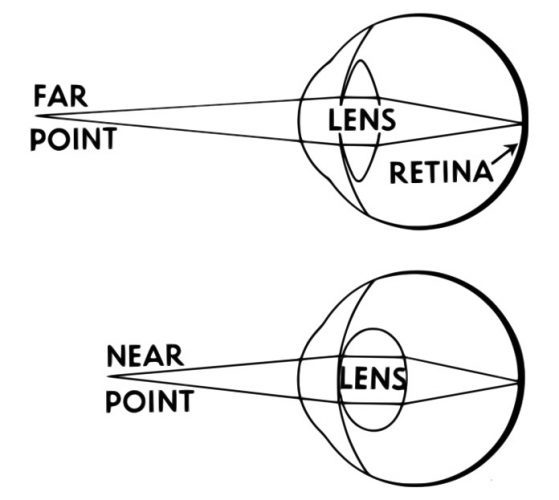

Eye tracking enables advanced display technologies like foveated rendering, which is one of the big reasons that it’s increasingly being included in consumer VR devices. Foveated rendering is a technique that improves the graphic fidelity of a small area of the overall display based on where your eye is looking at the moment.

AR devices currently don’t have a field-of-view large enough to benefit from foveated rendering, but Goldman said that Lumus will have a device with a field-of-view over 50 degrees before 2030.

Eye tracking also has promise as an advanced input system. Goldman cited the Apple Vision Pro, which uses a combination of eye tracking and hand-tracking to go completely controller-free. Mixed reality devices like the Apple Vision Pro and Meta Quest 3 also bring up the fact that eye tracking has different implications in AR than it does in VR.

“Effectively, you can know exactly where I’m looking and what I’m interested in, so it has its implications for advertisers,” said Goldman. “What’s less nefarious for me and more interesting as a user is contextual search.”

Power and Responsibility

As more advanced XR analytics tools come to more consumer-focused hardware, do we need to be concerned about these tools being turned on casual XR fans? It’s certainly something that we need to be watchful of.

“It’s certainly a sensitive issue,” said Goldman. “It’s certainly a concern for the consumer, so I think every company will have to address this up front.”

Bevilacqua explained that his company has adopted the XR Privacy Framework. Cognitive3D notifies individuals when certain kinds of data might be collected and gives them the option to opt out. However, Bevilacqua believes that the best option is to avoid certain kinds of data collection in the first place.

“It’s important to balance data collection with user privacy. … We have a pretty balanced view on what needs to be collected and what doesn’t,” said Bevilacqua. “For us, eye tracking is something we do not find acceptable in a consumer application.”

Bevilacqua also pointed out that platforms and marketplaces have their own internal guidelines that make it difficult for app developers to collect too much information on their own.

“There is acceptable use policy about what kinds of data exist and what can be used,” said Bevilacqua. “You can’t just go out and collect eye tracking data and use it for ads. That’s not something Meta is going to allow.”

All About Balance

We need XR analytics. They make for better experiences and can even improve the quality of goods and services that we enjoy and rely on in the physical world. Not to mention the benefits that the required hardware brings to consumer applications. While technologies like eye tracking can be scary if used irresponsibly, we seem to be in good hands so far.

How Eye Tracking Contributes to XR Analytics and Experience Read More »