Endurance tells story of two expeditions, centuries apart

New NatGeo documentary was directed by the same duo who brought us the Oscar-winning Free Solo.

The intact stern of the good ship Endurance. Credit: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust

The story of Arctic explorer Ernest Shackleton’s failed 1914 expedition to be the first to traverse the continent of Antarctica has long captured the popular imagination, as have the various efforts to locate the wreckage of his ship, the Endurance. The ship was finally found in 2022, nearly 107 years after it sank beneath the ice. The stories of Shackleton’s adventures and the 2022 expedition are told in parallel in Endurance, a new documentary from National Geographic now streaming on Disney+.

Endurance is directed by Oscar winners Jimmy Chin and Chai Vasarhelyi (Free Solo). According to Vasarhelyi, she and Chin had been obsessed with the Shackleton story for a long time. The discovery of the shipwreck in 2022 gave them the perfect opportunity to tell the story again for a new audience, making use of all the technological advances that have been made in recent years.

“I think the Shackleton story is at the heart of the DNA of our films,” Vasarhelyi told Ars. “It’s the greatest human survival story ever. It really speaks to having these audacious objectives and dreams. When everyone tells you that you can’t, you want to do it anyway. It requires you to then have the actual courage, grit, discipline, and strength of character to see it through. Shackleton is that story. He didn’t sensibly achieve any of his goals, but through his failure he found his strength: being able to inspire the confidence of his men.”

As previously reported, Endurance set sail from Plymouth on August 6, 1914, with Shackleton joining his crew in Buenos Aires, Argentina. By the time they reached the Weddell Sea in January 1915, accumulating pack ice and strong gales slowed progress to a crawl. Endurance became completely icebound on January 24, and by mid-February, Shackleton ordered the boilers to be shut off so that the ship would drift with the ice until the weather warmed sufficiently for the pack to break up. It would be a long wait. For 10 months, the crew endured the freezing conditions. In August, ice floes pressed into the ship with such force that the ship’s decks buckled.

The ship’s structure nonetheless remained intact, but by October 25, Shackleton realized Endurance was doomed. He and his men opted to camp out on the ice some two miles (3.2 km) away, taking as many supplies as they could with them. Compacted ice and snow continued to fill the ship until a pressure wave hit on November 13, crushing the bow and splitting the main mast—all of which was captured on camera by crew photographer Frank Hurley. Another pressure wave hit in the late afternoon on November 21, lifting the ship’s stern. The ice floes parted just long enough for Endurance to finally sink into the ocean before closing again to erase any trace of the wreckage.

When the sea ice finally disintegrated in April 1916, the crew launched lifeboats and managed to reach Elephant Island five days later. Shackleton and five of his men set off for South Georgia the next month to get help—a treacherous 720-mile journey by open boat. A storm blew them off course, and they ended up landing on the unoccupied southern shore. So Shackleton left three men behind while he and a companion navigated dangerous mountain terrain to reach the whaling station at Stromness on May 2. A relief ship collected the other three men and finally arrived back on Elephant Island in August. Miraculously, Shackleton’s crew was still alive.

Icebound

Ernest Shackleton aboard the Endurance. BF/Frank Hurley

Hurley’s photographs and footage—including Hurley’s 1919 feature documentary, South—were a crucial source for Vasarhelyi and Chin, as was the use of supplementary footage from 1920s and 1930s films depicting polar expeditions. The directors even convinced the British Film Institute to let them color-treat some of the original expedition footage.

“The BFI had lovingly restored the footage and been great custodians of it, but they also had been very strict about never color treating the footage,” said Vasarhelyi. “We made our argument and it shows what great partners they were that they agreed. It’s not colorized, it’s color treated, which is a slight difference. It just added drama and personality where suddenly you could kind of see the faces in a way that you couldn’t just by adding contrast. It was just trying to animate and identify and connect audiences with this story.”

The directors filmed original re-enactments for those parts of the Shackleton story that Hurley was not on hand to visually document firsthand, because he left his equipment behind when the crew was forced to abandon the Endurance. All he had after that was a small pocket camera. And Hurley wasn’t with Shackleton for the final rescue expedition. Most of the outdoor re-enactments were shot on location in Iceland, while some interior re-enactments were shot on a soundstage in Los Angeles.

This involved shooting under harsh freezing conditions on Icelandic glaciers in January and required building replica boats and sourcing period-specific costumes. Fortunately, “Burberry, who had made the original Shackleton gear, had the pattern still and they knew what type of leather it was,” said Vasarhelyi. “And so they made us 11 costume outfits that are the real costumes. We were able to source models of the real artifacts. The ice was freezing on the Burberry coats. The [re-enactors] had 9-millimeter wetsuits inside the Burberry outfits.”

Chin and Vasarhelyi also relied on the diaries of various crew members to capture the events in the crew’s voices. “The proper way into the Shackleton stories is through the diaries because you have primary accounts from many different points of view of the same events,” said Vasarhelyi. “But how to make it feel… vivid was the question.” The answer: using AI to reproduce the voices of Shackleton and others as preserved in historical recordings. They were able to sample those original voices and build an AI model from that, applying it to present-day voices (selected for their similarities to the original voices) reading the text.

Vasarhelyi acknowledges this was a controversial choice but defends the decision because it brought another dimension of immediacy to the final documentary. “Every part of me thinks that we have to educate ourselves; we need to regulate it,” she said. “I support our guilds in trying to protect our creative rights. But in this case, it was a good tool to use. For me, there was a real goosebump moment, watching Frank Hurley’s footage and you realize that you actually are watching real events that are 110 years old that were filmed by guys who survived two years in the ice without their boat. And then you add the tools of sound design and there is just something magical about it.“

The hunt for Endurance

The S.A. Agulhas II surrounded by sea ice as it makes its way toward the coordinates to find the Endurance. Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust/James Blake

People had been hunting for the wreckage of the Endurance ever since its sinking. Shackleton’s brilliant navigator, Frank Worsley, painstakingly calculated the coordinates for the position where Endurance sank using a sextant and chronometer. He recorded that position in his log book: 68°39’30” south; 52°26’30” west. But there was some question as to the accuracy of the marine chronometers he used to fix longitude, which would have affected the final coordinates.

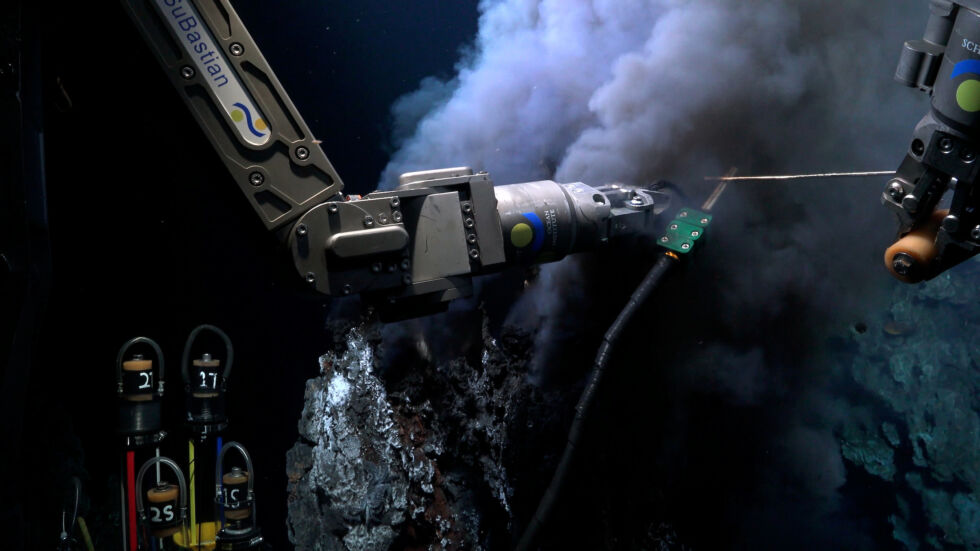

Organized by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust, the $10 million Endurance22 expedition team set sail from Cape Town, South Africa, in early February on board the icebreaker S.A. Agulhas II. They arrived at the search area 10 days later. To account for any navigational errors by Worsley, the search area was quite broad. The team used battery-powered submersibles to comb the ocean floor for six-hour stretches, twice a day, augmented with sonar scans of the seabed to hunt for any protrusions. There was a limited window to find the wreck before the ice froze up and trapped the S.A. Agulhas II (the expedition vessel) in the ice, much like the Endurance.

There was a moment when the 2022 expedition members thought they had succeeded, but the object glimpsed in the data turned out to be a debris field from the vessel, not the vessel itself. Still, it was a promising sign, and the expedition persevered. After all, “How can you be associated with the Shackleton story and give up?” said Vasarhelyi.

One sticking point was determining the direction of drift after the Endurance sank. The team had the idea of combining the original 1914 observations with an AI weather model created by the European Union and essentially running it backward to narrow the search further. “That’s another ‘good’ AI moment,” said Vasarhelyi. “It was one of those moments where the past spoke to the present that the whole movie turns on. But there is an argument that they could have maybe looked at this data a little earlier.”

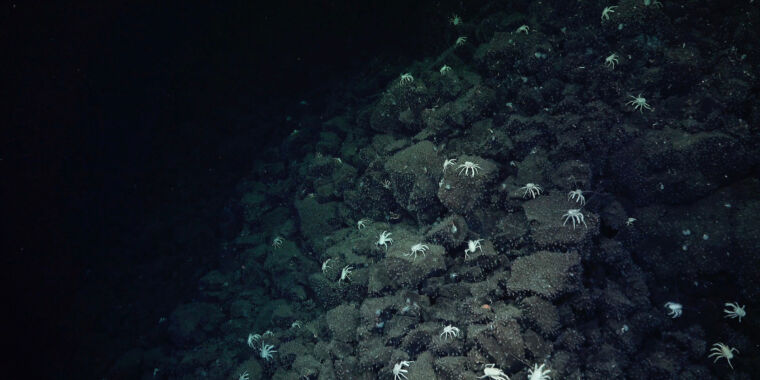

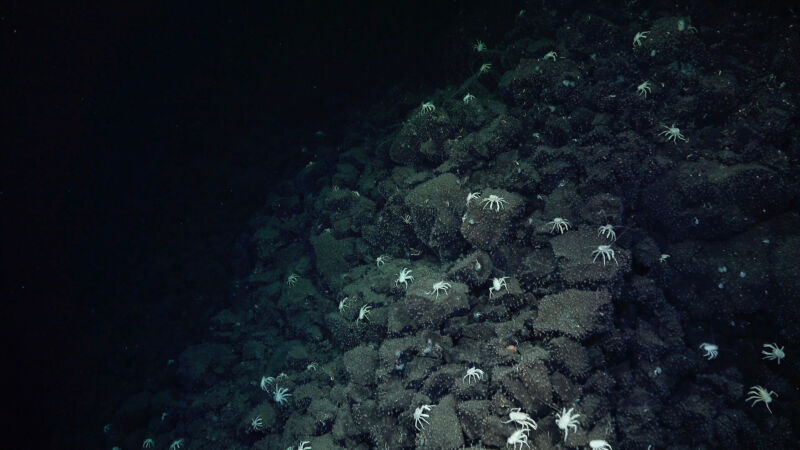

Finally, as the search was coming down to the wire, the Endurance22 team finally found the long-sought wreckage 3,008 meters down, roughly four miles (6.4 km) south of the ship’s last recorded position. The ship was in pristine condition partly because of the lack of wood-eating microbes in those waters. In fact, the Endurance22 expedition’s exploration director, Mensun Bound, told The New York Times at the time that the shipwreck was the finest example he’s ever seen; Endurance was “in a brilliant state of preservation.”

Once the wreck had been found, the team recorded as much as they could with high-resolution cameras and other instruments. Vasarhelyi, particularly, noted the technical challenge of deploying a remote digital 4K camera with lighting at 9,800 feet underwater, and the first deployment at that depth of photogrammetric and laser technology, resulting in a stunning millimeter-scale digital reconstruction of the entire shipwreck. “The payoff [was] seeing that incredible 3D imagery from 3,000 feet below the Weddell Sea,” she said.

What lies beneath

The Endurance as discovered underwater during the 2022 expedition. Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust

Chin and Vasarhelyi skillfully wove together these parallel storylines for their documentary: Shackleton and his men struggling to survive and Expedition22 racing against time to find the wreckage of the Endurance. “Because they actually found it, the 2022 expedition gave us an amazing payoff to this story,” said Vasarhelyi. “But the stakes of both narratives are very different. One is mortal stakes, and the other one is reputational. I think that the reasons why individuals find themselves in these circumstances are really interesting because normally they’re pretty personal, and people can identify with that.”

It was challenging to decide how much to include of both narrative threads; the directors certainly had enough material for five or more hours. They chose to focus on the broad strokes augmented by personal moments of humanity and occasional humor—not to mention heartbreak, such as the moment when Shackleton and his men are forced to kill their sled dogs for food. “We had a debate about whether to include the dogs, and I was like, ‘We have to,'” said Vasarhelyi. “It shows how desperate they were, and it also is a great character moment. That must have been awful, but it was the right thing to do, almost a merciful thing instead of letting them starve to death.”

Along with the tremendous courage and perseverance displayed by Shackleton and his men, Vasarhelyi said she was impressed with their grace under pressure. “I was astonished by the civility that Shackleton and his men depended on to preserve their humanity while they are in this dire circumstance, be it [putting on] burlesque shows or listening to the gramophone,” she said. “The story has an audacity and a strength of will that is inherently human and a view of leadership that felt so daring. This is really the holy grail of survival stories.”

Jennifer is a senior reporter at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

Endurance tells story of two expeditions, centuries apart Read More »