Everything you ever wanted to know about four-wheel steering

Like any big industry, the automotive business has several dumpsters filled with products and ideas that should have remained conceptual. From modern climate controls buried within successive infotainment menus that neither Lawrence of Arabia nor Columbo could find to the old and unlamented Chrysler TC by Maserati with its atrocious build quality and a terrible cylinder head (the Maserati part), the collective car circus has spawned no shortage of bad ideas.

However, there are a few good ideas buried under the weight of poor execution, lousy technology, dreadful marketing, steep pricing, or just merely something being ahead of its time. Several of these morsels deserved a better launch and a second chance. One of them is four-wheel steering.

Four-wheel steering, in concept

The idea of steering a two-axle vehicle’s front and rear wheels isn’t new. Very early American 4×4 trucks from the dawn of the 20th century sported four-wheel-steering systems (4WS), including the Cotta Cottamobile, the American ¾-ton to 10-ton trucks, and Jeffery/Nash Quad Lorry 3-ton trucks.

By the early 1980s, a more modern iteration of active 4WS systems was found as a feature on concept (show) cars. However, since that breed of machine rarely had to prove itself, these are more display pieces than working technology.

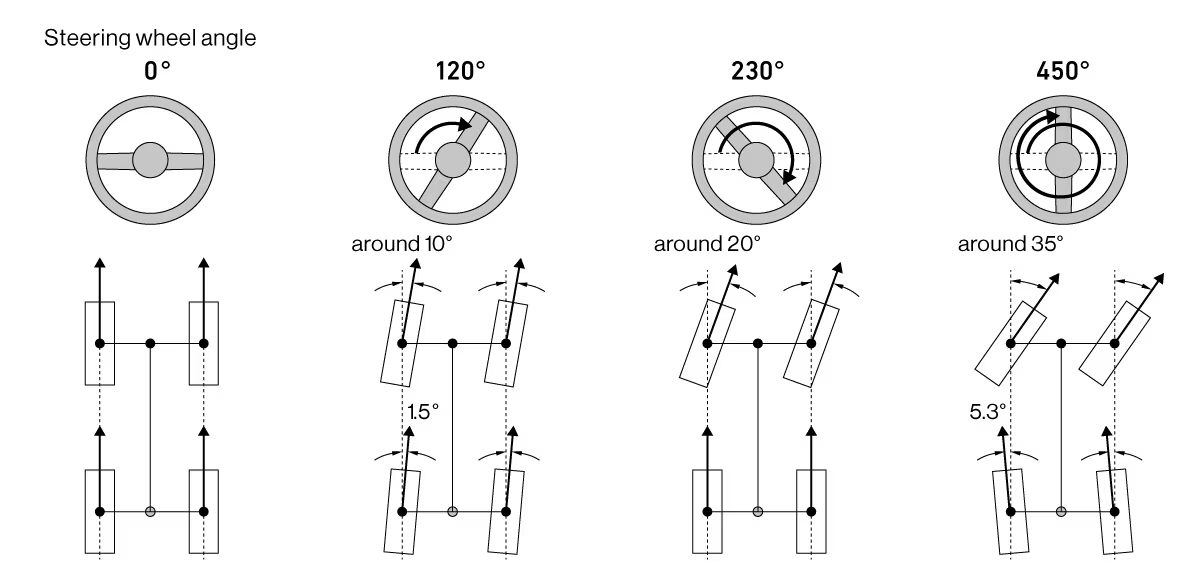

Active 4WS systems do two physical things. First, they impart opposite-phase steering angles to the rear wheels from those applied to the fronts. When the fronts turn right, the rears turn left at a fraction of the front’s steering angles. This effectively diminishes the vehicle’s turning circle or radius, making it more maneuverable in tight spaces like parking lots.

Credit: Honda

Depending on the system’s engineering, opposite-phase steering takes place only below a certain vehicle speed or with lots of steering lock applied (generally, more than three-quarters of a turn of the steering wheel or about 270 degrees of lock from center). It also never occurs above a trotting pace. Inducing opposite-phase steering above 30 or 40 mph could cause drastic instability at speed, creating a very rapid yaw moment that would likely cause an unrecoverable skid.

The second action of active 4WS is same-phase steering angle input to the rear wheels. Turn the wheel right, and the rear wheels also turn slightly to the right. However, that rear angle is even shallower than the opposite-phase angles in the above scenario. This improves higher-speed stability, like when a driver changes lanes or corners rapidly through fun twisties or on a racetrack. Rear steering angles vary anywhere from 2.5 degrees to 10 degrees, depending on vehicle design and purpose.

Four-wheel steering, in hard parts

In real nuts, bolts, and notoriety, Honda first brought 4WS to modern production in the 1988 Prelude Si as an option. Nissan followed suit with its HICAS system, and Mazda had a system with extremely limited production, but Honda made the biggest splash.

The Honda system was entirely mechanical. It used a shaft connecting the front steering rack to a planetary gear. That gear created the phase (direction) and degree of rear steering indexed to steering wheel input. This shaft led to a sliding rod that acted like the rack of a rack and pinion steering gear, carrying that input to the rear wheels.

At small steering angles, the rear wheels turned a maximum of 1.5 degrees in phase (in the same direction) as the fronts. At larger steering wheel angles above roughly 270 degrees from center, the rear wheels steered as much as 5.3 degrees out-of-phase with the fronts, tightening the turning circle about 10 percent.

The results in those 1980s and ’90s Preludes were impressive. Some auto critics, like that most cerebral of British scribes, L.J.K. Setright of Car Magazine, cited that the third and fourth-generation Honda Preludes with 4WS exuded the finest steering in the history of history. Weight, feel, accuracy, and telepathic information all sent the auto critic into automotive euphoria.

Four-wheel steering, digitally rendered

As Honda engineers toiled away on their system outside Tokyo, about 37 km away, Nissan worked on its HICAS (“High Capacity Actively Controlled Steering”) variants. Only active above roughly 90 km/h (55 mph) and below 200 km/h (125 mph), it used a computer-controlled hydraulic actuator to move the rear lower lateral links. A computer signaled a rear steering rack, allowing toe changes of plus or minus one degree, depending on speed and front steering angle.

The rear wheels of Nissan’s system would initially (and briefly) steer out of phase with the fronts to improve turn-in response. It then switched phasing for greater stability. This enabled excellent slalom performance with rapid directional changes, which Nissan considered important in contemporary vehicle reviews and tests of sporty vehicles at the time.

However, this early HICAS system had no rear steering at low speeds. The Nissan system also differed from Honda’s in that it relied on a variety of sensors to instruct operation, whereas Honda’s was entirely analog.

Other manufacturers had been working on 4WS at roughly the same time, and others even launched production cars with the system before Honda. Mazda’s MX-02 concept car in 1983 showed a real working system, reaching production in the 1988 626 Turbo. Mitsubishi had a system in the Galant VR-4 in 1987 that only steered with same-phase angles above 50 km/h (30 mph). But none made as big an impact as Honda’s.

However, 4WS did not take the world by storm in the marketplace. The complexity of sporty cars coming out of Japan in the 1980s grew enormously. Coupled with the Japanese Yen’s dramatic rise in value against the US dollar and after the Plaza Accord agreement in September 1985 between major industrial countries, the cost of Japanese cars in overseas markets skyrocketed. In the US, the 1984 Nissan 300ZX Turbo cost around $16,000. By 1990, the 300ZX Turbo’s MSRP was $33,260, more than doubling in just six years.

The bigger meaning for us in 2025 is that, conceptually, today’s 4WS systems essentially do the same thing. Slow-speed opposite-phase inputs tighten maneuverability. Same-phase steering at high speed improves directional changes like lane shifting with generally small steering angles at the rear.

Trucks

Even though the 4WS concept dates back to the early 20th-century trucks, GM is the only manufacturer that has produced a 4WS pickup in the modern era. (Ford has tested systems, though.) The initial Quadrasteer system of the 2000s used a set of trailing tie rods (behind the axle), leading to a steering rack, the pinion of which was an electric motor. This motor dialed a maximum of 15 degrees of steering angle out-of-phase with the front wheels, but only below 45 mph. Where a normal GM pickup had a turning circle of 47 feet, a Quadrasteer truck required only 37 feet, a giant 22 percent improvement.

The Quadrasteer’s in-phase rear-steering topped out at 5 degrees to improve highway stability at higher speeds. More importantly, since this was on a pickup truck, towing had to be considered, too. Therefore, GM limited the low-speed, opposite-phase steering angle in towing mode to 12 degrees. This prevented drastic angles from binding up a trailer while turning.

However, GM’s Quadrasteer system fell flat because of its high price. It didn’t cost the moon to produce, but GM priced it at $5,600. The company also made it optional only on the top trim levels of the Chevy Silverado and GMC Sierra.

GM also faced resistance among truck buyers because more complex mechanicals could mean a threat to durability. And if nothing else, pickup buyers want durability from their trucks, especially work trucks.

Modern-modern day

Today, 4WS is still not commonplace, but many luxury cars and SUVs use it for the same reasons that existed nearly 50 years ago when Honda, Nissan, and Mazda began their studies in the mid-1970s. Mercedes offers it today on several vehicles like the electric EQS, plus S-Class and E-Class models. And it is showing up on some large GM EVs, like the new Silverado and Hummer.

GMC offers a system on pickup trucks that aids low-speed maneuverability and allows the vehicle to crabwalk, changing direction with no yaw. Some high-powered Porsche models and top-level Audis use 4WS with slight variations, but all for the same fundamental reasons as in the 1970s and 1980s. Despite other developments in suspension design, computer aids, and active driving assists, which didn’t exist in the 1980s, the fundamental benefits of four-wheel steering—improved maneuverability at low speed and improved high-speed turning stability—still exist nearly 50 years after the concept first saw the light of day.

Everything you ever wanted to know about four-wheel steering Read More »