Neural network finds an enzyme that can break down polyurethane

You’ll often hear plastic pollution referred to as a problem. But the reality is that it’s multiple problems. Depending on the properties we need, we form plastics out of different polymers, each of which is held together by a distinct type of chemical bond. So the method we use to break down one type of polymer may be incompatible with the chemistry of another.

That problem is why, even though we’ve had success finding enzymes that break down common plastics like polyesters and PET, they’re only partial solutions to plastic waste. However, researchers aren’t sitting back and basking in the triumph of partial solutions, and they’ve now got very sophisticated protein design tools to help them out.

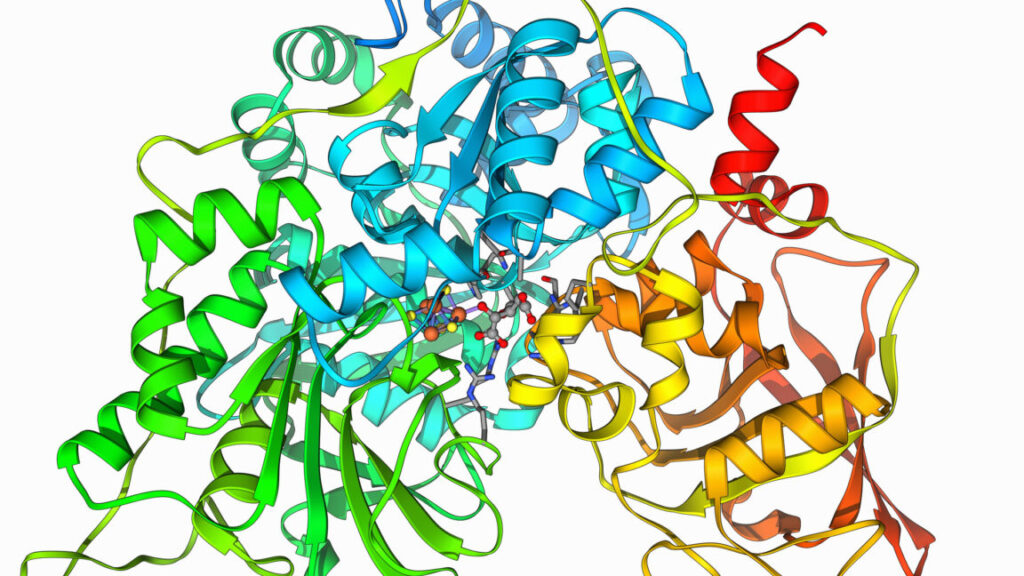

That’s the story behind a completely new enzyme that researchers developed to break down polyurethane, the polymer commonly used to make foam cushioning, among other things. The new enzyme is compatible with an industrial-style recycling process that breaks the polymer down into its basic building blocks, which can be used to form fresh polyurethane.

Breaking down polyurethane

The basics of the chemical bonds that link polyurethanes. The rest of the polymer is represented by X’s here.

The new paper that describes the development of this enzyme lays out the scale of the problem: In 2024, we made 22 million metric tons of polyurethane. The urethane bond that defines these involves a nitrogen bonded to a carbon that in turn is bonded to two oxygens, one of which links into the rest of the polymer. The rest of the polymer, linked by these bonds, can be fairly complex and often contains ringed structures related to benzene.

Digesting polyurethanes is challenging. Individual polymer chains are often extensively cross-linked, and the bulky structures can make it difficult for enzymes to get at the bonds they can digest. A chemical called diethylene glycol can partially break these molecules down, but only at elevated temperatures. And it leaves behind a complicated mess of chemicals that can’t be fed back into any useful reactions. Instead, it’s typically incinerated as hazardous waste.

Neural network finds an enzyme that can break down polyurethane Read More »