Coal likely to go away even without EPA’s power plant regulations

Set to be killed by Trump, the rules mostly lock in existing trends.

In April last year, the Environmental Protection Agency released its latest attempt to regulate the carbon emissions of power plants under the Clean Air Act. It’s something the EPA has been required to do since a 2007 Supreme Court decision that settled a case that started during the Clinton administration. The latest effort seemed like the most aggressive yet, forcing coal plants to retire or install carbon capture equipment and making it difficult for some natural gas plants to operate without capturing carbon or burning green hydrogen.

Yet, according to a new analysis published in Thursday’s edition of Science, they wouldn’t likely have a dramatic effect on the US’s future emissions even if they were to survive a court challenge. Instead, the analysis suggests the rules serve more like a backstop to prevent other policy changes and increased demand from countering the progress that would otherwise be made. This is just as well, given that the rules are inevitably going to be eliminated by the incoming Trump administration.

A long time coming

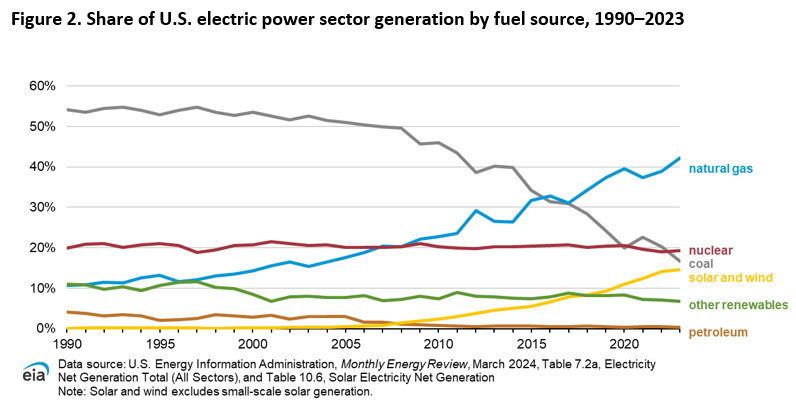

The net result of a number of Supreme Court decisions is that greenhouse gasses are pollutants under the Clean Air Act, and the EPA needed to determine whether they posed a threat to people. George W. Bush’s EPA dutifully performed that analysis but sat on the results until its second term ended, leaving it to the Obama administration to reach the same conclusion. The EPA went on to formulate rules for limiting carbon emissions on a state-by-state basis, but these were rapidly made irrelevant because renewable power and natural gas began displacing coal even without the EPA’s encouragement.

Nevertheless, the Trump administration replaced those rules with ones designed to accomplish even less, which were thrown out by a court just before Biden’s inauguration. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court stepped in to rule on the now-even-more-irrelevant Obama rules, determining that the EPA could only regulate carbon emissions at the level of individual power plants rather than at the level of the grid.

All of that set the stage for the latest EPA rules, which were formulated by the Biden administration’s EPA. Forced by the court to regulate individual power plants, the EPA allowed coal plants that were set to retire within the decade to continue to operate as they have. Anything that would remain operational longer would need to either switch fuels or install carbon capture equipment. Similarly, natural gas plants were regulated based on how frequently they were operational; those that ran less than 40 percent of the time could face significant new regulations. More than that, and they’d have to capture carbon or burn a fuel mixture that is primarily hydrogen produced without carbon emissions.

While the Biden EPA’s rules are currently making their way through the courts, they’re sure to be pulled in short order by the incoming Trump administration, making the court case moot. Nevertheless, people had started to analyze their potential impact before it was clear there would be an incoming Trump administration. And the analysis is valuable in the sense that it will highlight what will be lost when the rules are eliminated.

By some measures, the answer is not all that much. But the answer is also very dependent upon whether the Trump administration engages in an all-out assault on renewable energy.

Regulatory impact

The work relies on the fact that various researchers and organizations have developed models to explore how the US electric grid can economically meet demand under different conditions, including different regulatory environments. The researchers obtained nine of them and ran them with and without the EPA’s proposed rules to determine their impact.

On its own, eliminating the rules has a relatively minor impact. Without the rules, the US grid’s 2040 carbon dioxide emissions would end up between 60 and 85 percent lower than they were in 2005. With the rules, the range shifts to between 75 and 85 percent—in essence, the rules reduce the uncertainty about the outcomes that involve the least change.

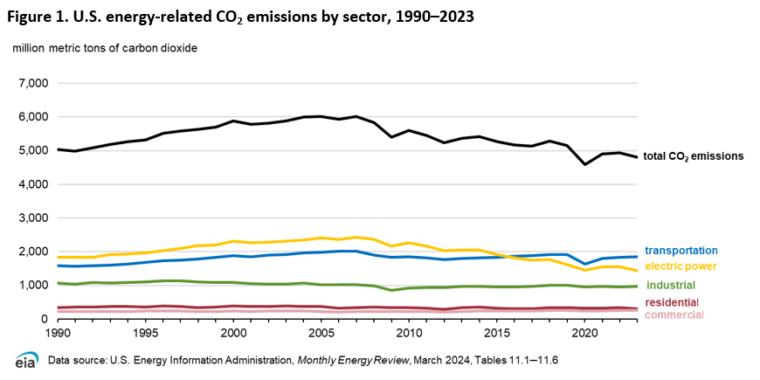

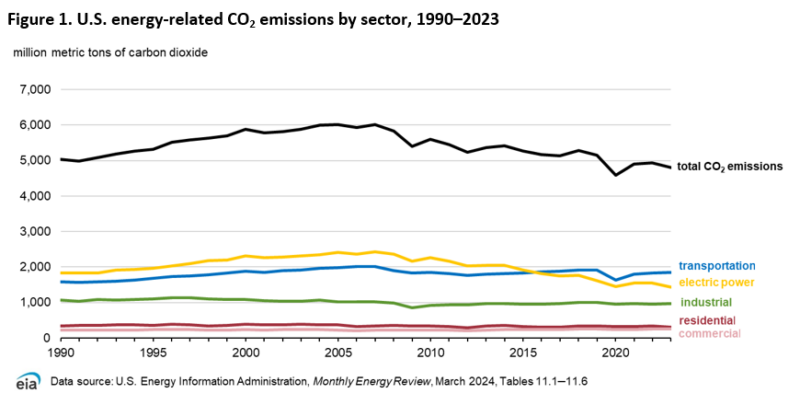

That’s primarily because of how they’re structured. Mostly, they target coal plants, as these account for nearly half of the US grid’s emissions despite supplying only about 15 percent of its power. They’ve already been closing at a rapid clip, and would likely continue to do so even without the EPA’s encouragement.

Natural gas plants, the other major source of carbon emissions, would primarily respond to the new rules by operating less than 40 percent of the time, thus avoiding stringent regulation while still allowing them to handle periods where renewable power underproduces. And we now have a sufficiently large fleet of natural gas plants that demand can be met without a major increase in construction, even with most plants operating at just 40 percent of their rated capacity. The continued growth of renewables and storage also contributes to making this possible.

One irony of the response seen in the models is that it suggests that two key pieces of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are largely irrelevant. The IRA provides benefits for the deployment of carbon capture and the production of green hydrogen (meaning hydrogen produced without carbon emissions). But it’s likely that, even with these credits, the economics wouldn’t favor the use of these technologies when alternatives like renewables plus storage are available. The IRA also provides tax credits for deploying renewables and storage, pushing the economics even further in their favor.

Since not a lot changes, the rules don’t really affect the cost of electricity significantly. Their presence boosts costs by an estimated 0.5 to 3.7 percent in 2050 compared to a scenario where the rules aren’t implemented. As a result, the wholesale price of electricity changes by only two percent.

A backstop

That said, the team behind the analysis argues that, depending on other factors, the rules could play a significant role. Trump has suggested he will target all of Biden’s energy policies, and that would include the IRA itself. Its repeal could significantly slow the growth of renewable energy in the US, as could continued problems with expanding the grid to incorporate new renewable capacity.

In addition, the US is seeing demand for electricity rise at a faster pace in 2023 than in the decade leading up to it. While it’s still unclear whether that’s a result of new demand or simply weather conditions boosting the use of electricity in heating and cooling, there are several factors that could easily boost the use of electricity in coming years: the electrification of transport, rising data center use, and the electrification of appliances and home heating.

Should these raise demand sufficiently, then it could make continued coal use economical in the absence of the EPA rules. “The rules … can be viewed as backstops against higher emissions outcomes under futures with improved coal plant economics,” the paper suggests, “which could occur with higher demand, slower renewables deployment from interconnection and permitting delays, or higher natural gas prices.”

And it may be the only backstop we have. The report also notes that a number of states have already set aggressive emissions reduction targets, including some for net zero by 2050. But these don’t serve as a substitute for federal climate policy, given that the states that are taking these steps use very little coal in the first place.

Science, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/science.adt5665 (About DOIs).

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

Coal likely to go away even without EPA’s power plant regulations Read More »