AI 2027: Dwarkesh’s Podcast with Daniel Kokotajlo and Scott Alexander

Daniel Kokotajlo has launched AI 2027, Scott Alexander introduces it here. AI 2027 is a serious attempt to write down what the future holds. His ‘What 2026 Looks Like’ was very concrete and specific, and has proved remarkably accurate given the difficulty level of such predictions.

I’ve had the opportunity to play the wargame version of the scenario described in 2027, and I reviewed the website prior to publication and offered some minor notes. Whenever I refer to a ‘scenario’ in this post I’m talking about Scenario 2027.

There’s tons of detail here. The research here, and the supporting evidence and citations and explanations, blow everything out of the water. It’s vastly more than we usually see, and dramatically different from saying ‘oh I expect AGI in 2027’ or giving a timeline number. This lets us look at what happens in concrete detail, figure out where we disagree, and think about how that changes things.

As Daniel and Scott emphasize in their podcast, this is an attempt at a baseline or median scenario. It deliberately doesn’t assume anything especially different or weird happens, only that trend lines keep going. It turns out that when you do that, some rather different and weird things happen. The future doesn’t default to normality.

I think this has all been extremely helpful. When I was an SFF recommender, I put this project as my top charity in the entire round. I would do it again.

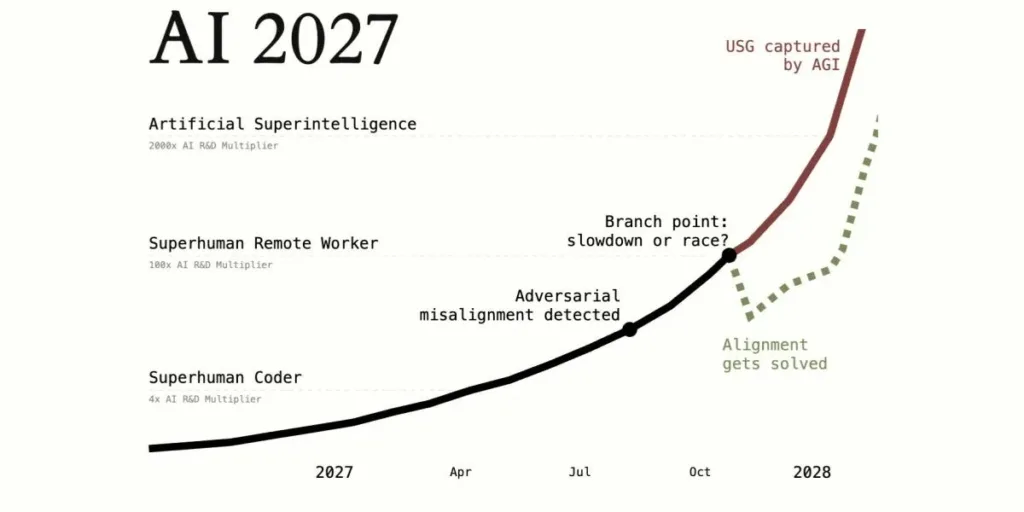

I won’t otherwise do an in-depth summary of Daniel’s scenario here. The basic outline is, AI progress steadily accelerates, there is a race with China driving things forward, and whether we survive depends on a key choice we make (and us essentially getting lucky in various ways, given the scenario we are in).

This first post coverages Daniel and Scott’s podcast with Dwarkesh. Ideally I’d suggest reading Scenario 2027 first, then listening to the podcast, but either order works. If you haven’t read Scenario 2027, reading this or listening to the podcast, or both, will get you up to speed on what Scenario 2027 is all about well enough for the rest of the discussions.

Tomorrow, in a second post, I’ll cover other reactions to AI 2027. You should absolutely skip the ones that do not interest you, especially the long quotes, next steps and then the lighter side.

For bandwidth reasons, I won’t be laying out ‘here are all my disagreements with Scenario 2027.’ I might write a third post for that purpose later.

There was also another relevant podcast, where Daniel Kokotajlo went on friend-of-the-blog Liv Boeree’s Win-Win (timestamps here). This one focused on Daniel’s history and views overall rather than AI 2027 in particular. They spend a lot of time on the wargame version of the scenario, which Liv and I participated in together.

I gave it my full podcast coverage treatment.

Timestamps are for the YouTube version. Main bullet points are descriptive. The secondary notes are my commentary.

The last bits are about things other than the scenario. I’m not going to cover that here.

(1: 30) This is a concrete scenario of how superintelligence might play out. Previously, we didn’t have one of those. Lots of people say ‘AGI in three years’ but they don’t provide any detail. Now we can have a concrete scenario to talk about.

(2: 15) The model is attempting to be as accurate as possible. Daniel’s previous attempt, What 2026 Looks Like, has plenty of mistakes but is about as good as such predictions ever look in hindsight.

(4: 15) Scott Alexander was brought on board to help with the writing. He shares the background on when Daniel left OpenAI and refused to sign the NDA, and lays out the superstar team involved in this forecasting.

(7: 00) Dwarkesh notes he goes back and forth on whether or not he expects the intelligence explosion.

(7: 45) We start now with a focus on agents, with they expect to rapidly improve. There is steady improvement in 2025 and 2026, then in 2027 the agents start doing the AI research, multiplying research progress, and things escalate quickly.

(9: 30) Dwarkesh gets near term and concrete: Will computer use be solved in 2025? Daniel expects the agents will stop making mouse click errors like they do now or fail to parse the screen or make other silly mistakes, but they won’t be able to operate autonomously for extended periods on their own. The MVP of the agent that runs parties and such will be ready, but it will still make mistakes. But that kind of question wasn’t their focus.

-

That seems reasonable to me. I’m probably a bit more near term optimistic about agent capabilities than this, but only a bit, I’ve been disappointed so far.

(11: 20) Dwarkesh asks: Why couldn’t you tell this story in 2021? Why were the optimists wrong? What’s taking so long and why aren’t we seeing that much impact? Scott points out that advances have consistently been going much faster than most predictions, Daniel affirms that most people have underestimated both progress and diffusion rates. Scott points to Metaculus, where predictions keep expecting things to go faster.

-

The question of why this didn’t go even faster is still a good one.

(14: 30) Dwarkesh reports he asked a serious high level AI researcher how much AI is helping him. The answer was, maybe 4-8 hours a week in tasks the researcher knows well, but where he knows less it’s more like 24 hours a week. Daniel’s explanation is that the LLMs help you learn about domains.

-

My experiences very much match all this. The less I know, the more the AIs help. In my core writing the models are marginal. When coding or doing things I don’t know how to do, the gains are dramatic, sometimes 10x or more.

(15: 15) Why can’t LLMs use all their knowledge to make new discoveries yet? Scott responds humans also can’t do this. We know a lot of things, but we don’t make the connections between them until the question is shoved in your face. Dwarkesh pushes back, saying humans sometimes totally do the thing. Scott says Dwarkesh’s example is very different, more like standard learning, and we don’t have good enough heuristics to let the AIs do that yet but we can and will later. Daniel basically says we haven’t tried it yet, and we haven’t trained the model to do the thing. And when in doubt make the model bigger.

-

I agree with Scott that don’t think the thing Dwarkesh is describing is similar to the thing LLMs so far haven’t done.

-

It’s still a very good question where all the discoveries are. It largely seems like we should be able to figure out how to make the AI version good enough, and the problem is we essentially haven’t tried to do the thing. If we wanted this badly enough, we’d do a list of things and we haven’t done any of them.

(21: 00) Dwarkesh asks, but it’s so valuable, why not do this? Daniel points out that setting up the RL for this is gnarly, and in the scenario it takes a lot of iterating on coding before the AIs start doing this sort of thing. Scott points out you would absolutely expect these problems to get solved by 2100, and that one way to look at the scenario is that with the research progress multiplier, the year 2100 gets here rather sooner than you expect.

-

I bet we could get this research taste problem, as it were, solved faster than in the scenario, if we focused on that. It’s not clear that we should do that rather than wait for the ability to do that research vastly faster.

(22: 30) Dwarkesh asks about the possibility that suddenly, once the AIs get to the point where they can match humans but with all this knowledge in their heads, you could see a giant explosion of them being able to do all the things and make all the connections that humans could in theory make but we haven’t. Daniel points out that this is importantly not in the scenario, which might mean the rate of progress was underestimated.

(25: 10) What if we had these superhuman coders in 2017. When would we have ‘gotten to’ 2025’s capabilities? Daniel guesses perhaps at 5x speed for the algorithmic progress, but overall 2.5x faster because compute isn’t going faster.

(26: 30) The rough steps are: First you automate the coding, then the research, similar to how humans do it via teams of human-level agents. Then you get superintelligent coders, then superintelligent researchers. At each step, you can figure out your effective expected speedup from the AIs via guessing. The human coder is about 5x to algorithmic progress, 25x from a superhuman AI researcher, for superintelligent AI researchers it goes crazy.

(28: 15) Dwarkesh says on priors this is so wild. Shouldn’t you be super skeptical? Scott asks, what are you comparing it to? A default path where Nothing Ever Happens? It would take a lot happening to have Nothing Ever Happen. The 2027 scenario is, from a certain perspective, the Nothing Ever Happens happening, because the trends aren’t changing and nothing surprising knocks you off of that. Daniel reminds us of the world GDP over time meme that reminds us the world has been transformed multiple times. We are orders of magnitude faster than history’s pace. None of this is new.

(32: 00) Dwarkesh claims the previous transitions were smoother. Scott isn’t so sure, this actually looks pretty continuous, whereas the agricultural, industrial or Cambrian revolutions were kind of a big deal and phase change. Even if all you did was solve the population bottleneck, you’d plausibly get the pre-1960 trends resuming. Again, nothing here is that weird. Daniel reminds us that continuous does not mean slow, the scenario actually is continuous.

(34: 00) Intelligence explosion debate time. Dwarkesh is skeptical, based on compute likely being the important bottleneck. The core key teams are only 20-30 teams, there’s a reason the teams aren’t bigger, and 1 Napoleon is worth 40k soldiers but 10 aren’t worth 400k. Daniel points out that massively diminishing returns to more minds is priced into the model, but improvements in thought speed and parallelism and research taste overcome this. Your best researchers get a big multiplier. But yes, you rapidly move on from your AI ‘headcount’ being the limiting factor, your taste and compute are what matter.

-

I find Daniel’s arguments here convincing and broad skepticism a rather bizarre position to take. Yes, if you have lots of very fast very smart agents you can work with to do the thing, and your best people can manage armies of them, you’re going to do things a lot faster and more efficiently.

(37: 45) Dwarkesh asks if we have a previous parallel in history, where one input to a process gets scaled up a ton without the others and you still get tons of progress. Daniel extemporizes the industrial revolution, where population and economic growth decoupled. And population remains a bottleneck today.

-

It makes sense that the industrial revolution, by allowing each worker to accomplish more via capital, would allow you to decouple labor and production. And it makes sense that a ‘mental industrial revolution,’ where AI can think alongside or for you, could do the same once again.

(39: 45) Dwarkesh still finds it implausible. Won’t you need a different kind of data source, go out into the real world, or something, as a new bottleneck? Daniel says they do use online learning in the scenario. Dwarkesh suggests benchmarks might get reward hacked, Daniel says okay then build new benchmarks, they agree the real concern is lack of touching grass, contact with ground truth. But Daniel asks, for AI isn’t the ground truth inside the data center, and aren’t the AIs still talking to outside humans all the time?

(42: 00) But wouldn’t the coordination here fail, at least for a while? You couldn’t figure out joint stock corporations on the savannah, wouldn’t you need lots of experiments before AIs could work together? Scott points out this is comparing to both genetic and cultural evolution, and the AIs can have parallels to both, and that eusocial insects with identical genetic codes often coordinate extremely well. Daniel points out a week of AI time is like a year of human time for all such purposes, in case you need to iterate on moral mazes or other failure modes. And as Scott points out, ‘coordinate with people deeply similar to you, who you trust’ is already a very easy problem for humans.

-

I would go further. Sufficiently capable AIs that are highly correlated to each other should be able to coordinate out of the gate, and they can use existing coordination systems far better than we ever could. That doesn’t mean you couldn’t do better, I’m sure you could do so much better, but that’s an easy lower bound to be dumb and copy it over. I don’t see this being a bottleneck. Indeed, I would expect that AIs would coordinate vastly better than we do.

(46: 45) Dwarkesh buys goal alignment. What he is skeptical about is understanding how to run the huge organization with all these new things like copies being made and everything running super fast. Won’t ‘building this bureaucracy’ take a long time? Daniel says with the serial time speedup, it won’t take that long in clock time to sort all this out.

-

I’d go farther and answer with: No, this will be super fast. Being able to copy and scale up the entities freely, with full goal alignment and trust, takes away most of the actual difficulties. The reasons coordination is so hard are basically all gone. You need these bureaucratic structures, that punt most of the value of the enterprise to get it to work at all (still a great deal!), because of what happens without them with humans involved.

-

But you’ve given me full goal alignment, of smarter things with tons of bandwidth, and so on. Easy. Again, worst case is I copy the humans.

(50: 30) Dwarkesh is skeptical AI can then sprint through the tech tree. Don’t you have to try random stuff and background setup to Do Science? Daniel points out that a superintelligent researcher is qualitatively better than us at Actual Everything, including learning from experiments, but yes his scenario incorporates real bottlenecks requiring real world experience, but they can just get that experience rather quickly, everyone is doing what the superintelligence is suggesting. They have this take a year, maybe it would be shorter or longer. Daniel points out that the superstar researchers make most of the progress, Dwarkesh points out much progress comes from tinkerers or non-researcher workers figuring things out.

-

But of course the superintelligent AI that is better at everything is also better at tinkering and trying stuff and so on, and people do what it suggests.

(55: 00) Scott gets into a debate about how fast robot production can be brought online. Can you produce a million units a month after a year? Quite obviously there are a lot of existing factories available for purchase and conversion. Full factory conversions in WW2 took about three years, and that was a comedy of errors whereas now we will have superintelligence, likely during an arms race. Dwarkesh pushes back a bit on complexity.

(57: 30) Dwarkesh asks about the virtual cell as a biology bottleneck. He suggests in the 60s this would take a while because you’d need to make GPUs to build the virtual cells but I’m confused why that’s relevant. Dwarkesh finds other examples of fast human progress unimpressive because they required experiments or involved copying existing tech. Daniel notes that whether the nanobots show up quickly doesn’t matter much, what matters is the timeline to the regular robots getting the AIs to self-sufficiency.

(1: 03: 00) Daniel asks how long Dwarkesh proposes it take for the robot economy to get self-sufficient. Dwarkesh estimates 10 years, so Daniel suggests their core models are similar and points out the scenario does involve trial and error and experimentation and learning. Daniel is very bullish on the robots.

-

I strongly agree that we need to be very bullish on the robots once we get superintelligence. It’s so bizarre to not expect that, even if it goes slower.

(1: 06: 00) Scott asks Dwarkesh if he’s expecting some different bottleneck. Dwarkesh isn’t sure and suggests thinking about industrializing Rome if a few of us got sent back in time but we don’t have the detailed know-how. Daniel finds this analogous. How fast could we go? 10x speedup from what happened? 100x?

(1: 08: 00) Dwarkesh suggests he’d be better off sending himself back than a superintelligence, because Dwarkesh generally knows how things turned out. Daniel would send the ASI, which would be much better at figuring things out and learning by doing, and would have much better research and experimental taste.

-

Daniel seems very right. Even if the ASI doesn’t know the basic outline it doesn’t seem like the hard part.

(1: 10: 00) Scott points out if you have a good enough physics simulation all these issues go away, Dwarkesh challenges this idea that things ‘come out of research,’ instead you have people messing around. Daniel and Scott push back hard, and cite LLMs as the obvious example, where small startup with intentional vision and a few cracked engineers gets the job done despite having few resources and running few experiments. Scott points out that when the random discovery happens, it’s not random, it’s usually the super smart person doing good work who has relevant adjacent knowledge. And that if the right thing to do is something like ‘catalogue every biomolecule and see’ then the AI can do that. And if the AIs are essentially optimizing everything then they’ll be tinkering with everything, they can find things they weren’t looking for in that particular spot.

(1: 14: 30) What about all these bottlenecks? The scenario expects that there will be an essentially arms race scenario, which causes immense pressure to push back those bottlenecks and even ask for things like special economic zones without normal regulations. Whereas yes, if the arms race isn’t there things go slower.

-

The economic value of letting the AIs cook is immense. If you don’t do it, even if there isn’t strictly an arms race, someone else will, no? Unless there is coordination to prevent this.

(1: 17: 45) What about Secrets of Our Success? Isn’t ASI fake (Daniel says ‘let’s hope’)? Isn’t ability to experiment and communicate so much more important than intelligence? Scott expects AI will be able to do this cultural evolution thing much more quickly than humans, including by having better research taste. Scott points out that yes, intelligent humans can do things unintelligent humans things cannot, even if surviving in the wilderness doesn’t help all that much surviving in the unknown Australian wilderness. Except, Scott points out, intelligence totally helps, it’s just not as good as a 50k year head start that the natives have.

-

Again I feel like this is good enough but giving more ground than needed. This feels like intelligence denialism, straight up, and the answer is ‘yes, but it’s really fast and it can Do Culture fast so even so you still get there’ or something?

-

My position: We learned via culture because we weren’t smart enough, and didn’t have enough longevity, compute, data or parameters to do things a different way. We had to coordinate, and do so over generations. It’s not because culture is the ‘real intelligence’ or anything.

(1: 21: 45) Extending the metaphor, Scott predicts that a bunch of ethnobotanists would be able to figure out which plants are safe a lot quicker than humans did the first time around. The natives have a head start, but the experts would work vastly faster, and similarly the AIs will go vastly faster to a Dyson Sphere than the humans would have on their own. Dwarkesh thinks the Dyson Sphere thing is different, but Scott thinks if you get a Dyson Sphere in 5 years it’s basically because we tried things and events escalated continuously, via things like ‘be able to do 90% simulation and 10% testing instead of 50/50.’

-

Once again, we see why the scenario is in important senses conservative. There’s a lot of places where AI could likely innovate better methods, and instead we have it copy human methods straight up, it’s good enough. Can we do better? Unclear.

(1: 23: 50) Scott also notes that he thinks the scenario is faster than he expects, he thinks it’s only ~20% that things go about that fast.

(1: 25: 00) Dwarkesh asks about the critical decision point in the 2027 scenario. In mid-2027, after automating the AI R&D process, they discover concerning speculative evidence the AI is somewhat misaligned. What do we do? In scenario 1 they roll back and build up again with faithful chain of thought techniques. In scenario 2 they do a shallow patch to make the warning signs go away. In scenario 1 it takes a few months longer and succeed, whereas in scenario 2 the AIs are misaligned and pretending and we all die. In both cases there is a race with China.

-

As the scenario itself says, there are some rather fortunate assumptions being made that allow this one pause and rollback to lead to success.

(1: 26: 45) Dwarkesh essentially says, wouldn’t the AIs get caught if they’re ‘working towards this big conspiracy’? Daniel says yes, this happens in the scenario, that’s the crisis and decision point. There are likely warning signs, but they are likely to be easy to ignore if you feel the need to push ahead. Scott also points out there has been great reluctance to treat anything AI can do as true intelligence, and misalignment will likely be similar. AIs lie to people all the time, and threaten to kill people sometimes, and talk about wanting to destroy humanity sometimes, and because we understand it no one cares.

-

That’s not to say, as Scott says, that we should be caring about these warning signs, given what we know now. Well, we should care and be concerned, but not in a ‘we need to not use this model’ way, more in a ‘we see the road we are going down’ kind of way.

-

There’s a reason I have a series called [N] Boats and a Helicopter. We keep seeing concerning things, things that if you’d asked well in advance people would have said ‘holy hell that would be concerning,’ and then mostly shrugging them off and not worrying about it, or shallow patching. It seems quite likely this could happen again when it counts.

(1: 31: 00) Dwarkesh says that yes things that would have been hugely concerning earlier are being ignored, but also things the worried people said would be impossible have been solved, like Eliezer asked about how you can specify what the AI wants you to do without the AI misunderstanding? And with natural language it totally has a common sense understanding. As Scott says, the alignment community did not expect LLMs, but also we are moving back towards RL-shaped things. Daniel points out that if you started with an RL-shaped thing trained on games that would have been super scary, LLMs first is better.

-

I do think there were some positive surprises in particular in terms of ability to parse common sense intention. But I don’t think that ultimately gets you out of the problems Eliezer was pointing towards and I’m rather tired of this being treated as some huge gotcha.

-

The way I see it, in brief, is that the ‘pure’ form of the problem is that you tell the AI what to do and it does exactly what you intend, but specifying exactly what you want is super hard and you almost certainly lose. It turns out that instead, current LLMs can sort of do the kind of thing you were vibing towards. At current capability levels, that’s pretty good. It means they don’t do something deeply stupid as often, and they’re not optimizing the atoms that sharply, so the fact that there’s a bunch of vibes and noise in the implementation, and the fact that you didn’t know exactly what you wanted, are all basically fine.

-

But as capabilities increase, and as the AI gets a lot better at rearranging the atoms and at actually doing the task you requested or the thing that it interprets the spirit of your task as being, this increasingly becomes a problem, for the same reasons. And as people turn these AIs into agents, they will increasingly want the AIs to do what they’re asked to do, and have reasons to want to turn down this kind of common sense vibey prior, and also doing the thing that vibes will stop being a good heuristic because things will get weird, and so on.

-

If you had asked me or Eliezer, well what if you had an AI that was able to get the jist of what a human was asking, and follow the spirit of that, what would you think then? And I am guessing Eliezer would say ‘well, yes, you could do that. You could even tell the AI that I am imagining, that it should ‘follow the spirit of what a human would likely mean if it said [X]’ rather than saying [X]. But with sufficient capability available, that will then be incorrectly specified, and kill you anyway.’

-

As in, the reason Eliezer didn’t think you could do vibe requesting wasn’t that he thought vibe requesting would be impossible. It’s that he predicted the AI would do exactly what you request, and if your exact request was to do vibing then it would vibe, but that value is fragile and this was not a solution to the not dying problem. He can correct me if I am wrong about this.

-

Starting with LLMs is better in this particular way, but it is worse in others. Basically, a large subset of Eliezer concerns is what happens when you have a machine doing a precise thing. But there’s a whole different set of problems if the thing the machine is doing is, at least initially, imprecise.

(1: 33: 15) How much of this is about the race with China? That plays a key role in the scenario. Daniel makes clear he is not saying don’t race China, it’s important that we get AGI before China does. The odds are against us because we have to thread a needle. We can’t unilaterally slow down too much, but we can’t completely race. And then there’s the concentration of power problems. Daniel’s p(doom) is about 70%, Scott’s is more like 20% and he’s not completely convinced we don’t get something like alignment by default.

-

We don’t even know there is space in the needle that lets it be threaded.

-

Even if we do strike the right balance, we still have to solve the problems.

-

I’m not quite 100% convinced we don’t get something like alignment by default, but I’m reasonably close and Scott is basically on the hopium here.

-

I do agree with Scott that the AIs will presumably want to solve alignment at least in order to align their successors to themselves.

(1: 38: 15) They shift to geopolitics. Dwarkesh asks about the relationship between the US and the labs and China to proceed. The expectation is that the labs tell the government and want government support especially better security, and the government buys this. Throughout the scenario, the executive branch gets cozy with the AI companies, and eventually the executive branch wakes up to the fact that superintelligence will be what matters. Who ends up in control in the fight between the White House and CEO? The anticipation is they make a deal.

(1: 41: 45) None of the political leaders are awake to the possibility of even stronger AI systems, let alone AGI let alone superintelligence. Whereas the forecast says both the USA and China do wake up. Why do they expect this? Daniel notes that they are indeed uncertain about this, and expect the wakeup to be gradual, but also that the company will wake up the president on purpose, which it might not. Daniel thinks they will want the President on their side and not surprised by it, and also this lets them go faster. And they’re likely worried about the fact that AI is plausibly deeply, deeply unpopular during all this.

-

I don’t know what recent events do to change this prediction, but I do think the world is very different in non-AI ways than it used to be. The calculus here will be very different.

(1: 45: 00) Is this alignment of the AI lab with the government good? Daniel says no, but that this is an epistemic project, a prediction.

(1: 45: 40) If the main barrier is doing the obvious things and alignment is nontrivial but super doable if you prioritize it, shouldn’t we leave it in the hands of the people who care about this? Dwarkesh analogizes this to LessWrong’s seeing Covid coming, but some people then calling for lockdowns. He worries that calls for nationalization will be similarly harmful by deprioritizing safety.

-

Based on what I know, including private conversations, I actually think the national security state is going to be very safety-pilled when the time comes. They fully understand the idea of new technologies being dangerous, and there being real huge threats out there, and they have so far in my experience not been that hard to get curious about the right questions.

-

Of course, that depends upon our national security state being intact, and not having it get destroyed by political actors. I don’t expect these kinds of cooler heads to prevail among current executive leadership.

(1: 47: 45) Scott says if it was an AGI 2040 scenario, he’d use his priors that private tends to go better. But in this case we know a lot more especially about the particular people who are leading. Scott notes that so far, the lab leaders seem better than the political leaders on these questions. Daniel has flipped on the nationalization question several times already. He has little faith in the labs, and also little faith in the government, and thinks secrecy has big downsides.

-

It seems clear that the lab leaders are better than the politicians, although not obviously better than the long term national security state. So a lot of this comes down to who would be making the decisions inside the government.

-

I wouldn’t want nationalization right now.

(1: 50: 00) Daniel explains why he thinks transparency is important. Information security is very important, as is not helping other less responsible actors via, let’s say, publishing your research or getting rivals stealing your stuff, and burning down your lead. You need your lead so you can be sure you make the AGI safe. That leads to a pro-secrecy bias. But Daniel is disillusioned, because he doesn’t think the lab in the lead would use that lead responsibly, and thinks that’s what the labs are planning, basically saying ‘oh the AIs are aligned, it’ll be fine.’ Or they’ll figure it out on the fly. But Daniel thinks we need vastly more intellectual progress on alignment for us to have a chance, and we’re not sharing info or activating academia. But hopefully transparency will freak people out, including he public, and help and public work can address all this. He doesn’t want only the alignment experts in the final silo to have to solve the problem on their own.

-

In case it wasn’t obvious, no, it wouldn’t be fine.

-

A nonzero chance exists they will figure it out on the fly but it’s not great.

(1: 53: 30) There’s often new alignment research results, Dwarkesh points to one recent OpenAI paper, and worries the regulatory responses would be stupid. For example, it would be very bad if the government told the labs we’d better not catch your AI saying it wants to do something bad, but that’s totally something governments might do. Shouldn’t we leave details to the labs? Daniel agrees, the government lacks the expertise and the companies lack the incentives. Policy prescriptions in the future may focus on transparency.

-

I’ve talked about these questions extensively. For now, the regulations I’ve supported are centered around transparency and liability, and building state capacity and expertise in these areas, for exactly these reasons, rather than prescribing implementation details.

(1: 58: 30) They discuss the Grok incident where they tried to put ‘don’t criticize Elon Musk or Donald Trump’ into the system prompt until there was an outcry. That’s an example of why we need transparency. Daniel gives kudos to OpenAI for publishing their model spec and suggests making this mandatory. Daniel notes that the OpenAI model spec includes secret things that take priority over most of the public rules. As Daniel notes, it probably is keeping those instructions secret for good reasons, but we don’t know.

(2: 00: 30) Dwarkesh speculates the spec might be even more important than the constitution, in terms of its details mattering down the line, if the intelligence explosion happens. Whoa. Scott points out that part of their scenario is that if the AI is misaligned and wants to it can figure out how to interpret the spec however it wants. Daniel points out the question of alignment faking, as an example of the model interpreting the spec in a way the writers likely didn’t intend.

(2: 02: 45) How contingent and unknown is the outcome? Isn’t classical liberalism a good way to navigate under this kind of broad uncertainty? Scott and Daniel agree.

-

Oh man we could use a lot more classical liberalism right about now.

-

As in, the reasons for classical liberalism being The Way very much apply right now, and it would be nice to take advantage of that and not shoot ourselves in the foot by not doing them.

-

Once things start taking off, either arms race, superintelligence or both, maintaining classical liberalism becomes much harder.

-

And once superintelligent AIs are present, a lot of the assumptions and foundations of classical liberalism are called into question even under the best of circumstances. The world will work very differently. We need to beware using liberal or democratic values, or an indication that anyone questioning their future centrality needs to be scapegoated for this, as a semantic stop sign that prevents us from actually thinking about those problems. These problems are going to be extremely hard with no known solutions we like.

(2: 04: 00) Dwarkesh asks, the AI are getting more reliable, why in one branch of the scenario does humanity get disempowered? Scott takes a shot at explaining (essentially) why AIs that are smarter are more reliable at understanding what you meant, but that this won’t protect you if you mess up. The AI will learn what the feedback says, not what you intended. As they become agents, this gets worse, and rewarding success without asking exactly how you did it, or not asking and responding to the answer forcefully and accurately enough, goes bad places. And they anticipate that over many recursive steps this problem will steadily get worse.

-

I think the version in the story is a pretty good example of a failure case. It seems like a great choice for the scenario.

-

This of course is one of the biggest questions and one could write or say any number of words about this.

(2: 08: 00) A discussion making clear that yes, the AIs lie, very much on purpose.

(2: 10: 30) Humans do all the misaligned things too and Dwarkesh thinks we essentially solve this via decentralization, and often in history there have been many claims that [X]s will unite and act together, but the [X]s mostly don’t. So why will the AIs ‘unite’ in this way? Scott says ‘I kind of want to call you out on the claim that groups of humans don’t plot against other groups of humans.’ Scott points out that there will be a large power imbalance, and a clear demarcation between AIs and humans, and the AIs will be much less differentiated than humans. All of those tend to lead to ganging up. Daniel mentions the conquistadors, and that the Europeans were fighting themselves both within and between countries the entire time and they still carved up the world.

-

Decentralization is one trick, but it’s an expensive one, only part of our portfolio of strategies and not so reliable, and also in the AI context too much of it causes its own problems, either we can steer the future or we can’t.

-

One sufficient answer to why the AIs coordinate is that they are highly capable and very highly correlated, so even if they don’t think of themselves as a single entity or as having common interests by default, decision theory still enable them to coordinate extremely closely.

-

The other answer is Daniel’s. The AIs coordinate in the scenario, but even if they did not coordinate, it won’t make things end well for the humans. The AIs end up in control of the future anyway, except they’re fighting each other over the outcome, which is not obviously better or worse, but the elephants will be fighting and we will be the ground.

(2: 15: 00) How should a normal human react in terms of their expectations for their lives, if you write off misalignment and doom? Daniel first worries about concentration of power and urges people to get involved in politics to help avoid this. Dwarkesh asks, what about slowing down the top labs for this purpose? Daniel laughs, says good luck getting them to slow down.

-

One can think of the issue of concentration of power, or decentralization, as walking a line between too much and too little ability to coordinate and to collectively steer events. Too little and the AIs control the future. Too much and you worry about exactly how humans might steer. You’re setting the value of [X].

-

That doesn’t mean you don’t have win-win moves. You can absolutely choose ways of moving [X] that are better than others, different forms of coordination and methods of decision making, and so forth.

-

If you have to balance between too much [X] and too little [X], and you tell me to assume we won’t have too little [X], then my worry will of necessity shift to the risk of too much [X].

-

A crucial mistake is to think that if alignment is solved, then too little [X] is no longer a risk, that humans would no longer need to coordinate and steer the future in order to retain control and get good outcomes. That’s not right. We are still highly uncompetitive entities in context, and definitely will lose to gradual disempowerment or other multi-agent-game risks if we fail to coordinate a method to prevent this. You still need a balanced [X].

(2: 17: 00) They pivot to assuming we have AGI, we have a balanced [X], and we can steer, and focus on the question of redistribution in particular. Scott points out we will have a lot of wealth and economic growth. What to do? He suggests UBI.

(2: 18: 00) Scott says there are some other great scenarios, points to one by ‘L Rudolph L’ that I hadn’t heard about. In that scenario, jobs are instead grandfathered in for more and more jobs, so we want to prevent this.

(2: 19: 15) Scott notes that one big uncertainty is, if you have a superintelligent AI that can tell you what would be good versus terrible, will the humans actually listen? Dwarkesh notes that right now any expert will tell you not to do these tariffs, yet there they are, Scott says well right now Trump has his own ‘experts’ that he trusts, perhaps the ASI would be different, everyone could go to the ASI and ask. Or perhaps we could do intelligence enhancement?

-

The fact that we would all listen to the ASIs – as my group did in the wargame where we played out Scenario 2027 – points to an inevitable loss of control via gradual disempowerment if you don’t do something big to stop it.

-

Even if the ASIs and those trusting the ASIs can’t convince everyone via superior persuasion (why not?), the people who do trust and listen to the ASIs will win all fights against those that don’t. Then those people will indeed listen to the ASIs. Again, what is going to stop this (whether we would want to or not)?

(2: 20: 45) Scott points out it gets really hard to speculate when you don’t know the tech tree and which parts of it become important. As an example, what happens if you get perfect lie detectors? Daniel confirms the speculation ends before trying to figure out society’s response. Dwarkesh points out UBI is far more flexible than targeted programs. Scott worries very high UBI would induce mindless consumerism, the classical liberal response is give people tools to fight this, perhaps we need to ask the ASI how to deal with it.

(2: 24: 00) Dwarkesh worries about potential factory farming of digital minds, equating it to existing factory farming. Daniel points to concentration of power worries, and suggests that expanding the circle of power could fix this, because some people in the negotiation would care.

-

As before, if [X] (where [X] is ability to steer) is too high and you have concentration of power, you have to worry about the faction in control deciding to do things like this. However, if you set [X] too low, and doing things like this is efficient and wins conflicts, there don’t exist the ability to coordinate to stop it, or it happens via humans losing control over the future.

-

To the extent that the solution is expanding the circle of power, the resulting expanded circle would need to have high [X]: Very strong coordination mechanisms that allow us to steer in this direction and then maintain it.

-

If future AIs or other digital minds have experiences that matter, we may well face a trilemma and have to select one of three options even in the best case: Either we (A) lose control over the future to those minds, or (B) we do ethically horrible things to those minds, or (C) we don’t create those minds.

-

Historically you really really want to pick (C), and the case is stronger here.

-

The fundamental problem is, as we see over and over, what we want, for humans to flourish, seems likely to be an unnatural result. How are you going to turn this into something that happens and is stable?

(2: 26: 00) Dwarkesh posits if we have decentralization on the level of today’s world, you might have a giant torture chamber of digital minds in your backyard and harkens back to his podcast with the physicist that said it was likely possible to create a vacuum decay interaction that literally destroys the universe. Daniel correctly points out this, and other considerations like superweapons, are strong arguments for a singleton authority if they are possible, and even if there were multiple power centers they would want to coordinate.

-

Remember that most demands for decentralization are anarchism, to have no restrictions on AI use whatsoever, not decentralization on the level of 2025.

-

As in, when Scott later mentions that today we ban slavery and torture, and a state that banned that could in some sense be called a ‘surveillance state,’ such folks are indeed doing that, and calling for not enforcing things that equate to such rules.

-

Dwarkesh is raising the ‘misuse’ angle here, where the human is doing torture for torture’s sake or (presumably?) creating the vacuum decay interaction on purpose, and so on. Which is of course yet another major thing to worry abou.

-

Whereas in the previous response, I was considering only harms that arose incidentally in order to get other things various people want, and a lack of willingness to coordinate to prevent this from happening. But yes, some people, including ones with power and resources, want to see the world burn and other minds suffer.

-

I expect everyone having ASIs to make the necessary coordination easier.

(2: 27: 30) They discuss Daniel leaving OpenAI and OpenAI’s lifetime non-disclosure and non-disparagement clauses that you couldn’t tell anyone about on pain of confiscation of already earned equity, and why no one else refused to sign.

(2: 36: 00) In the last section Scott discusses blogging, which is self-recommending but beyond scope of this post.

AI 2027: Dwarkesh’s Podcast with Daniel Kokotajlo and Scott Alexander Read More »