Large genome model: Open source AI trained on trillions of bases

System can identify genes, regulatory sequences, splice sites, and more.

Late in 2025, we covered the development of an AI system called Evo that was trained on massive numbers of bacterial genomes. So many that, when prompted with sequences from a cluster of related genes, it could correctly identify the next one or suggest a completely novel protein.

That system worked because bacteria tend to cluster related genes together—something that’s not true in organisms with complex cells, which tend to have equally complex genome structures. Given that, our coverage noted, “It’s not clear that this approach will work with more complex genomes.”

Apparently, the team behind Evo viewed that as a challenge, because today it is describing Evo 2, an open source AI that has been trained on genomes from all three domains of life (bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes). After training on trillions of base pairs of DNA, Evo 2 developed internal representations of key features in even complex genomes like ours, including things like regulatory DNA and splice sites, which can be challenging for humans to spot.

Genome features

Bacterial genomes are organized along relatively straightforward principles. Any genes that encode proteins or RNAs are contiguous, with no interruptions in the coding sequence. Genes that perform related functions, like metabolizing a sugar or producing an amino acid, tend to be clustered together, allowing them to be controlled by a single, compact regulatory system. It’s all straightforward and efficient.

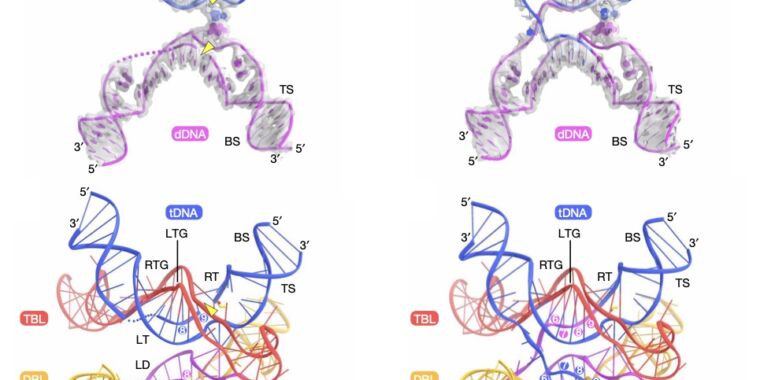

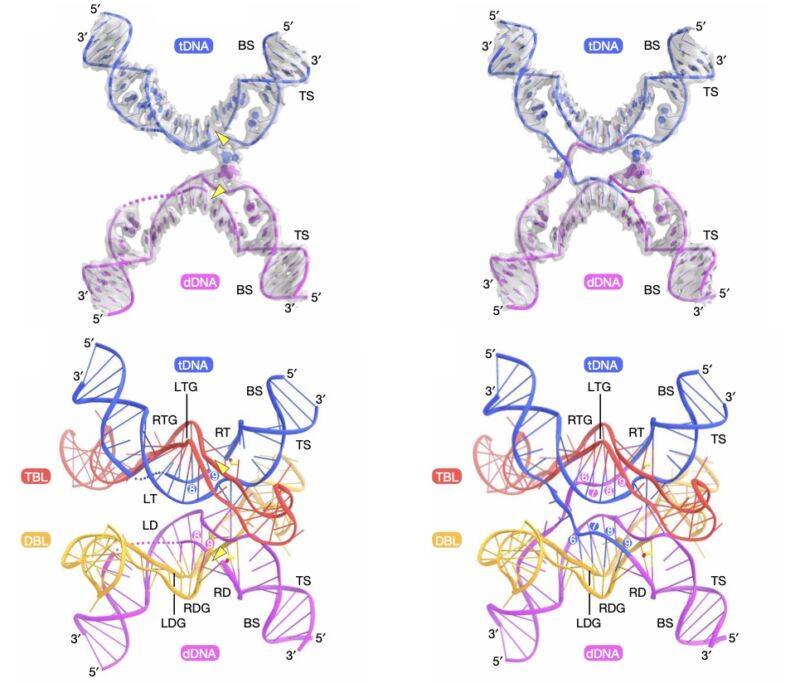

Eukaryotes are not like that. The coding sections of genes are interrupted by introns, which don’t encode for anything. They’re regulated by a sequence that can be scattered across hundreds of thousands of base pairs. The sequences that define the edges of introns or the binding sites of regulatory proteins are all weakly defined—while they have a few bases that are absolutely required, there are a lot of bases that just have an above-average tendency to have a specific base (something like “45 percent of the time it’s a T”). Surrounding all of this in most eukaryotic genomes is a huge amount of DNA that has been termed junk: inactive viruses, terminally damaged genes, and so on.

That complexity has made eukaryotic genomes more difficult to interpret. And, while a lot of specialized tools have been developed to identify things like splice sites, they’re all sufficiently error-prone that it becomes a problem when you’re analyzing something as large as a 3 billion-base-long genome. We can learn a lot more by making evolutionary comparisons and looking for sequences that have been conserved, but there are limits to that, and we’re often as interested in the differences between species.

These sorts of statistical probabilities, however, are well-suited to neural networks, which are great at recognizing subtle patterns that can be impossible to pick out by eye. But you’d need absolutely massive amounts of data and computing time to process it and pick out some of these subtle features.

We now have the raw genome data that the process needs. Putting together a system to feed it into an effective AI training program, however, remained a challenge. That’s the challenge the team behind Evo took on.

Training a large genome model

The foundation of the Evo 2 system is a convolutional neural network called StripedHyena 2. The training took place in two stages. The initial stage focused on teaching the system to identify important genome features by feeding it sequences rich in them in chunks about 8,000 bases long. After that, there was a second stage in which sequences were fed a million bases at a time to provide the system the opportunity to identify large-scale genome features.

The researchers trained two versions of their system using a dataset called OpenGenome2, which contains 8.8 trillion bases from all three domains of life, as well as viruses that infect bacteria. They did not include viruses that attack eukaryotes, given that they were concerned that the system could be misused to create threats to humans. Two versions were trained: one that had 7 billion parameters tuned using 2.4 trillion bases, and the full version with 40 billion parameters trained on the full open genome dataset.

The logic behind the training is pretty simple: if something’s important enough to have been evolutionarily conserved across a lot of species, it will show up in multiple contexts, and the system should see it repeatedly during training. “By learning the likelihood of sequences across vast evolutionary datasets, biological sequence models capture conserved sequence patterns that often reflect functional importance,” the researchers behind the work write. “These constraints allow the models to perform zero-shot prediction without any task-specific fine-tuning or supervision.”

That last aspect is important. We could, for example, tell it about what known splice sites look like, which might help it pick out additional ones. But that might make it harder for it to recognize any unusual splice sites that we haven’t recognized yet. Skipping the fine-tuning might also help it identify genome features that we’re not aware of at all at the moment, but which could become apparent through future research.

All of this has now been made available to the public. “We have made Evo 2 fully open, including model parameters, training code, inference code, and the OpenGenome2 dataset,” the paper announces.

The researchers also used a system that can identify internal features in neural networks to poke around inside of Evo 2 and figure out what things it had learned to recognize. They trained a separate neural network to recognize the firing patterns in Evo 2 and identify high-level features in it. It clearly recognized protein-coding regions and the boundaries of the introns that flanked them. It was also able to recognize some structural features of proteins within the coding regions (alpha helices and beta sheets), as well as mutations that disrupt their coding sequence. Even something like mobile genetic elements (which you can think of as DNA-level parasites) ended up with a feature within Evo 2.

What is this good for?

To test the system, the researchers started making single-base mutations and fed them into Evo 2 to see how it responded. Evo 2 could detect problems when the mutations affected the sites in DNA where transcription into RNA started, or the sites where translation of that RNA into protein started. It also recognized the severity of mutations. Those that would interrupt protein translation, such as the introduction of stop signals, were identified as more significant changes than those that left the translation intact.

It also recognized when sequences weren’t translated at all. Many key cellular functions are carried out directly by RNAs, and Evo 2 was able to recognize when mutations disrupted those, as well.

Impressively, the ability to recognize features in eukaryotic genomes occurred without the loss of its ability to recognize them in bacteria and archaea. In fact, the system seemed to be able to work out what species it was working in. A number of evolutionary groups use genetic codes with a different set of signals to stop the translation of proteins. Evo 2 was able to recognize when it was looking at a sequence from one of those species, and used the correct genetic code for them.

It was also good at recognizing features that tolerate a lot of variability, such as sites that signal where to splice RNAs to remove introns from the coding sequence of proteins. By some measures, it was better than software specialized for that task. The same was true when evaluating mutations in the BRCA2 gene, where many of the mutations are associated with cancer. Given additional training on known BRCA2 mutations, its performance improved further.

Overall, Evo 2 seems great for evaluating genomes and identifying key features. The researchers who built it suggest it could serve as a good automated tool for preliminary genome annotation.

But the striking thing about the early version of Evo was that, when prompted with a chunk of sequence that includes known bacterial genes, some of its responses included entirely new proteins with related functions. Now that it was trained on more complex eukaryotic genes, could it do the same?

We don’t entirely know. If given a bunch of DNA from yeast (a eukaryote), it would respond with a sequence that included functional RNAs, and gene-like sequences with regulatory information and splice sites. But the researchers didn’t test whether any of the proteins did anything in particular. And it’s difficult to see how they could even do that test. With bacterial genes, they could safely assume that the AI-generated gene should be doing something related to the nearby genes. But that’s generally not the case in eukaryotes, so it’s difficult to guess what functions they should even test for.

In a somewhat more informative test, the researchers asked Evo 2 to make some regulatory DNA that was active in one cell type and not another after giving it information about what sequences were active in both those cell types. The sequences that came out were then inserted into these cells and tested, but the results were pretty weak, with only 17 percent having activity that differed by a factor of two or more between the two cell types. That’s a major achievement, but it isn’t in the same realm as designing brand new proteins.

What’s next?

Overall, given that this has come out less than four months after the paper describing the original Evo, it’s not at all surprising that there wasn’t more work done to test what Evo 2 can do for designing biologically relevant DNA sequences. Biology experiments are hard and time-consuming, and it’s not always easy to judge in advance which ones will provide the most compelling information. So we’ll probably have to wait months to years to find out whether the community finds interesting things to do with Evo 2, and whether it’s good at solving any useful protein design problems.

There’s also the question of whether further training and specialization can create Evo 2 relatives that are especially good at specific tasks, such as evaluating genomes from cancer cells or annotating newly sequenced genomes. To an extent, it appears the research team wanted to get this out so that others could start exploring how it might be put to use; that’s consistent with the fact that all of the software was made available.

The big open question is whether this system has identified anything that we don’t know how to test for. Things like intron/exon boundaries and regulatory DNA have been subjected to decades of study so that we already knew how to look for them and can recognize when Evo 2 spots them. But we’ve discovered a steady stream of new features in the genome—CRISPR repeats, microRNAs, and more—over the past decades. It remains technically possible that there are features in the genome we’re not aware of yet, and Evo 2 has picked them out.

It’s possible to imagine ways to use the tools described here to query Evo 2 and pick out new genome features. So I’m looking forward to seeing what might ultimately come out of that sort of work.

Nature, 2026. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-026-10176-5 (About DOIs).

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

Large genome model: Open source AI trained on trillions of bases Read More »