Wyoming dinosaur mummies give us a new view of duck-billed species

Exquisitely preserved fossils come from a single site in Wyoming.

The scaly skin of a crest over the back of the juvenile duck-billed dinosaur Edmontosaurus annectens. Credit: Tyler Keillor/Fossil Lab

Edmontosaurus annectens, a large herbivore duck-billed dinosaur that lived toward the end of the Cretaceous period, was discovered back in 1908 in east-central Wyoming by C.H. Sternberg, a fossil collector. The skeleton, later housed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and nicknamed the “AMNH mummy,” was covered by scaly skin imprinted in the surrounding sediment that gave us the first approximate idea of what the animal looked like.

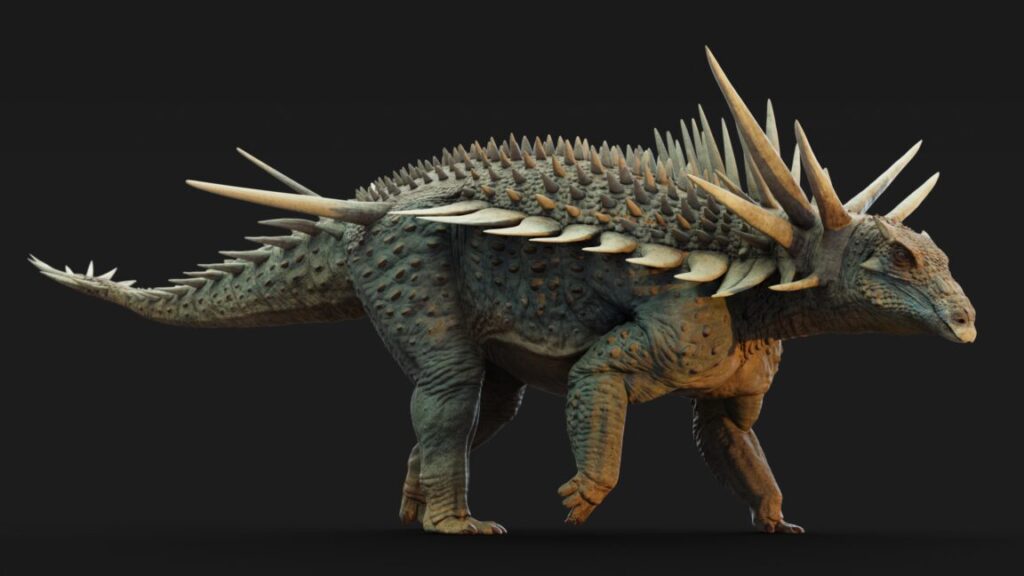

More than a century later, a team of paleontologists led by Paul C. Sereno, a professor of organismal biology at the University of Chicago, got back to the same exact place where Sternberg dug up the first Edmontosaurus specimen. The researchers found two more Edmontosaurus mummies with all fleshy external anatomy imprinted in a sub-millimeter layer of clay. For the first time, we uncovered an accurate image of what Edmontosaurus really looked like, down to the tiniest details, like the size of its scales and the arrangement of spikes on its tail. And we were in for at least a few surprises.

Evolving images

Our view of Edmontosaurus changed over time, even before Sereno’s study. The initial drawing of Edmontosaurus was made in 1909 by Charles R. Knight, a famous paleoartist, who based his visualization on the first specimen found by Sternberg. “He was accurate in some ways, but he made a mistake in that he drew the crest extending throughout the entire length of the body,” Sereno says. The mummy Knight based his drawing on had no tail, so understandably, the artist used his imagination to fill in the gaps and made the Edmontosaurus look a little bit like a dragon.

An update to Knight’s image came in 1984 due to Jack Horner, one of the most influential American paleontologists, who found a section of Edmontosaurus tail that had spikes instead of a crest. “The specimen was not prepared very accurately, so he thought the spikes were rectangular and didn’t touch each other,” Sereno explains. “In his reconstruction he extended the spikes from the tail all the way to the head—which was wrong,” Sereno says. Over time, we ended up with many different, competing visions of Edmontosaurus. “But I think now we finally nailed down the way it truly looked,” Sereno claims.

To nail it down, Sereno’s team retraced the route to where Sternberg found the first Edmontosaurus mummy. This was not easy, because the team had to rely on Sternberg’s notes, which often referred to towns and villages that were no longer on the map. But based on interviews with Wyoming farmers, Sereno managed to reach the “mummy zone,” an area less than 10 kilometers in diameter, surprisingly abundant in Cretaceous fossils.

“To find dinosaurs, you need to understand geology,” Sereno says. And in the “mummy zone,” geological processes created something really special.

Dinosaur templating

The fossils are found in part of the Lance Formation, a geological formation that originated in the last three or so million years of the Cretaceous period, just before the dinosaurs’ extinction. It extends through North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, and even to parts of Canada. “The formation is roughly 200 meters thick. But when you approach the mummy zone—surprise! The formation suddenly goes up to a thousand meters thick,” Sereno says. “The sedimentation rate in there was very high for some reason.”

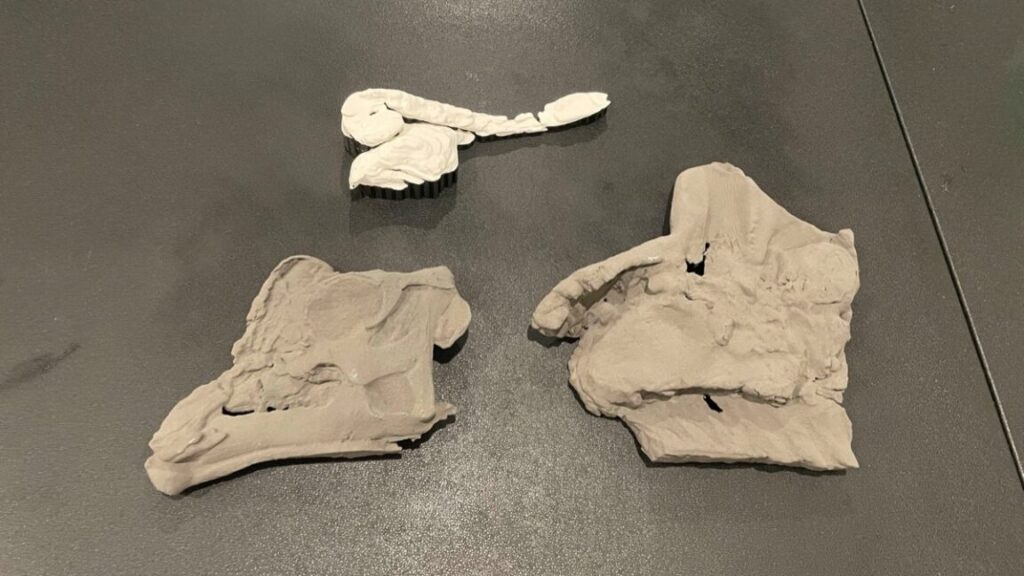

Sereno thinks the most likely reason behind the high sedimentation rate was frequent and regular flooding of the area by a nearby river. These floods often drowned the unfortunate dinosaurs that roamed there and covered their bodies with mud and clay that congealed against a biofilm which formed at the surface of decaying carcasses. “It’s called clay templating, where the clay sticks to the outside of the skin and preserves a very thin layer, a mask, showing how the animal looked like,” Sereno says.

Clay templating is a process well-known by scientists studying deep-sea invertebrate organisms because that’s the only way they can be preserved. “It’s just no one ever thought it could happen to a large dinosaur buried in a river,” Sereno says. But it’s the best explanation for the Wyoming mummy zone, where Sereno’s team managed to retrieve two more Edmontosaurus skeletons surrounded by clay masks under 1 millimeter thick. These revealed the animal’s appearance with amazing, life-like accuracy.

As a result, the Edmontosaurus image got updated one more time. And some of the updates were rather striking.

Delicate elephants

Sereno’s team analyzed the newly discovered Edmontosaurus mummies with a barrage of modern imaging techniques like CT scans, X-rays, photogrammetry, and more. “We created a detailed model of the skin and wrapped it around the skeleton—some of these technologies were not even available 10 years ago,” Sereno says. The result was an updated Edmontosaurus image that includes changes to the crest, the spikes, and the appearance of its skin. Perhaps most surprisingly, it adds hooves to its legs.

It turned out both Knight and Horner were partially right about the look of Edmontosaurus’ back. The fleshy crest, as depicted by Knight, indeed started at the top of the head and extended rearward along the spine. The difference was that there was a point where this crest changed into a row of spikes, as depicted in the Horner version. The spikes were similar to the ones found on modern chameleons, where each spike corresponds one-to-one with the vertebrae underneath it.

“Another thing that was stunning in Edmontosaurus was the small size of its scales,” Sereno says. Most of the scales were just 1 to 4 millimeters across. They grew slightly larger toward the bottom of the tail, but even there they did not exceed 1 centimeter. “You can find such scales on a lizard, and we’re talking about an animal the size of an elephant,” Sereno adds. The skin covered with these super-tiny scales was also incredibly thin, which the team deduced from the wrinkles they found in their imagery.

And then came the hooves. “In a hoof, the nail goes around the toe and wraps, wedge-shaped, around its bottom,” Sereno explains. The Edmontosaurus had singular, central hooves on its fore legs with a “frog,” a triangular, rubbery structure at the underside. “They looked very much like equine hooves, so apparently these were not invented by mammals,” Sereno says. “Dinosaurs had them.” The hind legs that supported most of the animal’s weight, on the other hand, had three wedge-shaped hooves wrapped around three digits and a fleshy heel toward the back—a structure found in modern-day rhinos.

“There are so many amazing ‘firsts’ preserved in these duck-billed mummies,” Sereno says. “The earliest hooves were documented in a land vertebrate, the first confirmed hooved reptile, and the first hooved four-legged animal with different forelimb and hindlimb posture.” But Edmontosaurus, while first in many aspects, was not the last species Sereno’s team found in the mummy zone.

Looking for wild things

“When I was walking through the grass in the mummy zone for the first time, the first hill I found a T. rex in a concretion. Another mummy we found was a Triceratops,” Sereno says. Both these mummies are currently being examined and will be covered in the upcoming papers published by Sereno’s team. And both are unique in their own way.

The T. rex mummy was preserved in a surprisingly life-like pose, which Sereno thinks indicates the predator might have been buried alive. Edmontosaurus mummies, on the other hand, were positioned in a death pose, which meant the animals most likely died up to a week before the mud covered their carcasses. This, in principle, should make the T. rex clay mask even more true-to-life, since there should be no need to account for desiccation and decay when reconstructing the animal’s image.

Sereno, though, seems to be even more excited about the Triceratops mummy. “We already found Triceratops scales were 10 times larger than the largest scales on the Edmontosaurus, and its skin had no wrinkles, so it was significantly thicker. And we’re talking about animals of similar size living in the same area and in the same time,” Sereno says. To him, this could indicate that the physiology of the Triceratops and Edmontosaurus was radically different.

“We are in the age of discovery. There are so many things to come. It’s just the beginning,” Sereno says. “Anyway, the next two mummies we want to cover are the Triceratops and the T. Rex. And I can already tell you what we have with the Triceratops is wild,” he adds.

Science, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/science.adw3536

Wyoming dinosaur mummies give us a new view of duck-billed species Read More »