10 things I learned from burning myself out with AI coding agents

If you’ve ever used a 3D printer, you may recall the wondrous feeling when you first printed something you could have never sculpted or built yourself. Download a model file, load some plastic filament, push a button, and almost like magic, a three-dimensional object appears. But the result isn’t polished and ready for mass production, and creating a novel shape requires more skills than just pushing a button. Interestingly, today’s AI coding agents feel much the same way.

Since November, I have used Claude Code and Claude Opus 4.5 through a personal Claude Max account to extensively experiment with AI-assisted software development (I have also used OpenAI’s Codex in a similar way, though not as frequently). Fifty projects later, I’ll be frank: I have not had this much fun with a computer since I learned BASIC on my Apple II Plus when I was 9 years old. This opinion comes not as an endorsement but as personal experience: I voluntarily undertook this project, and I paid out of pocket for both OpenAI and Anthropic’s premium AI plans.

Throughout my life, I have dabbled in programming as a utilitarian coder, writing small tools or scripts when needed. In my web development career, I wrote some small tools from scratch, but I primarily modified other people’s code for my needs. Since 1990, I’ve programmed in BASIC, C, Visual Basic, PHP, ASP, Perl, Python, Ruby, MUSHcode, and some others. I am not an expert in any of these languages—I learned just enough to get the job done. I have developed my own hobby games over the years using BASIC, Torque Game Engine, and Godot, so I have some idea of what makes a good architecture for a modular program that can be expanded over time.

In December, I used Claude Code to create a multiplayer online clone of Katamari Damacy called “Christmas Roll-Up.” Credit: Benj Edwards

Claude Code, Codex, and Google’s Gemini CLI, can seemingly perform software miracles on a small scale. They can spit out flashy prototypes of simple applications, user interfaces, and even games, but only as long as they borrow patterns from their training data. Much like a 3D printer, doing production-level work takes far more effort. Creating durable production code, managing a complex project, or crafting something truly novel still requires experience, patience, and skill beyond what today’s AI agents can provide on their own.

And yet these tools have opened a world of creative potential in software that was previously closed to me, and they feel personally empowering. Even with that impression, though, I know these are hobby projects, and the limitations of coding agents lead me to believe that veteran software developers probably shouldn’t fear losing their jobs to these tools any time soon. In fact, they may become busier than ever.

So far, I have created over 50 demo projects in the past two months, fueled in part by a bout of COVID that left me bedridden with a laptop and a generous 2x Claude usage cap that Anthropic put in place during the last few weeks of December. As I typed furiously all day, my wife kept asking me, “Who are you talking to?”

You can see a few of the more interesting results listed on my personal website. Here are 10 interesting things I’ve learned from the process.

1. People are still necessary

Even with the best AI coding agents available today, humans remain essential to the software development process. Experienced human software developers bring judgment, creativity, and domain knowledge that AI models lack. They know how to architect systems for long-term maintainability, how to balance technical debt against feature velocity, and when to push back when requirements don’t make sense.

For hobby projects like mine, I can get away with a lot of sloppiness. But for production work, having someone who understands version control, incremental backups, testing one feature at a time, and debugging complex interactions between systems makes all the difference. Knowing something about how good software development works helps a lot when guiding an AI coding agent—the tool amplifies your existing knowledge rather than replacing it.

As independent AI researcher Simon Willison wrote in a post distinguishing serious AI-assisted development from casual “vibe coding,” “AI tools amplify existing expertise. The more skills and experience you have as a software engineer the faster and better the results you can get from working with LLMs and coding agents.”

With AI assistance, you don’t have to remember how to do everything. You just need to know what you want to do.

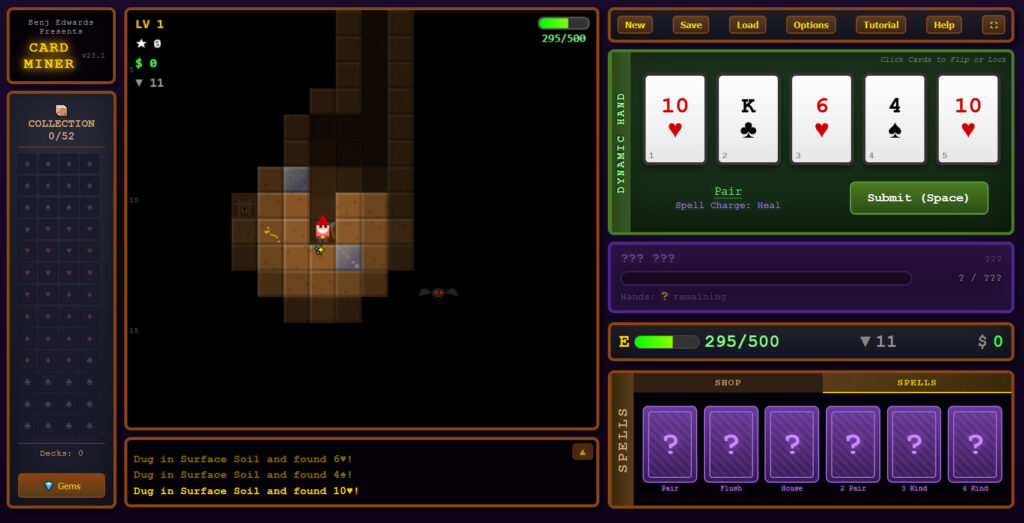

Card Miner: Heart of the Earth is entirely human-designed, but it was AI-coded using Claude Code. It represents about a month of iterative work. Credit: Benj Edwards

So I like to remind myself that coding agents are software tools best used to enact human ideas, not autonomous coding employees. They are not people (and not people replacements) no matter how the companies behind them might market them.

If you think about it, everything you do on a computer was once a manual process. Programming a computer like the ENIAC involved literally making physical bits (connections) with wire on a plugboard. The history of programming has been one of increasing automation, so even though this AI-assisted leap is somewhat startling, one could think of these tools as an advancement similar to the advent of high-level languages, automated compilers and debugger tools, or GUI-based IDEs. They can automate many tasks, but managing the overarching project scope still falls to the person telling the tool what to do.

And they can have rapidly compounding benefits. I’ve now used AI tools to write better tools—such as changing the source of an emulator so a coding agent can use it directly—and those improved tools are already having ripple effects. But a human must be in the loop for the best execution of my vision. This approach has kept me very busy, and contrary to some prevailing fears about people becoming dumber due to AI, I have learned many new things along the way.

2. AI models are brittle beyond their training data

Like all AI models based on the Transformer architecture, the large language models (LLMs) that underpin today’s coding agents have a significant limitation: They can only reliably apply knowledge gleaned from training data, and they have a limited ability to generalize that knowledge to novel domains not represented in that data.

What is training data? In this case, when building coding-flavored LLMs, AI companies download millions of examples of software code from sources like GitHub and use them to make the AI models. Companies later specialize them for coding through fine-tuning processes.

The ability of AI agents to use trial and error—attempting something and then trying again—helps mitigate the brittleness of LLMs somewhat. But it’s not perfect, and it can be frustrating to see a coding agent spin its wheels trying and failing at a task repeatedly, either because it doesn’t know how to do it or because it previously learned how to solve a problem but then forgot because the context window got compacted (more on that here).

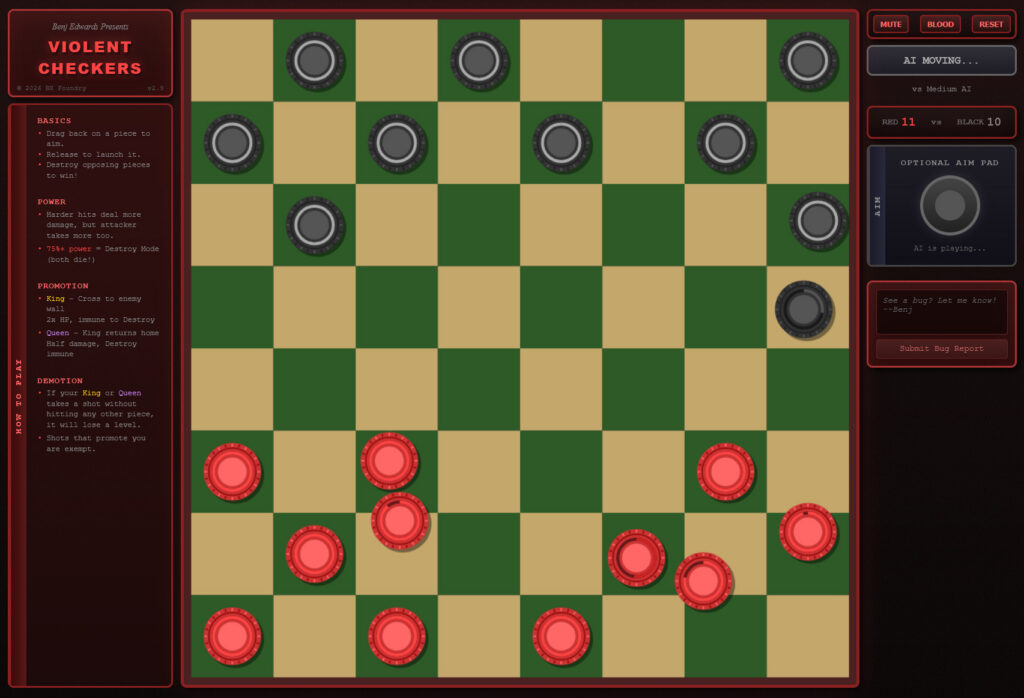

Violent Checkers is a physics-based corruption of the classic board game, coded using Claude Code. Credit: Benj Edwards

To get around this, it helps to have the AI model take copious notes as it goes along about how it solved certain problems so that future instances of the agent can learn from them again. You also want to set ground rules in the claude.md file that the agent reads when it begins its session.

This brittleness means that coding agents are almost frighteningly good at what they’ve been trained and fine-tuned on—modern programming languages, JavaScript, HTML, and similar well-represented technologies—and generally terrible at tasks on which they have not been deeply trained, such as 6502 Assembly or programming an Atari 800 game with authentic-looking character graphics.

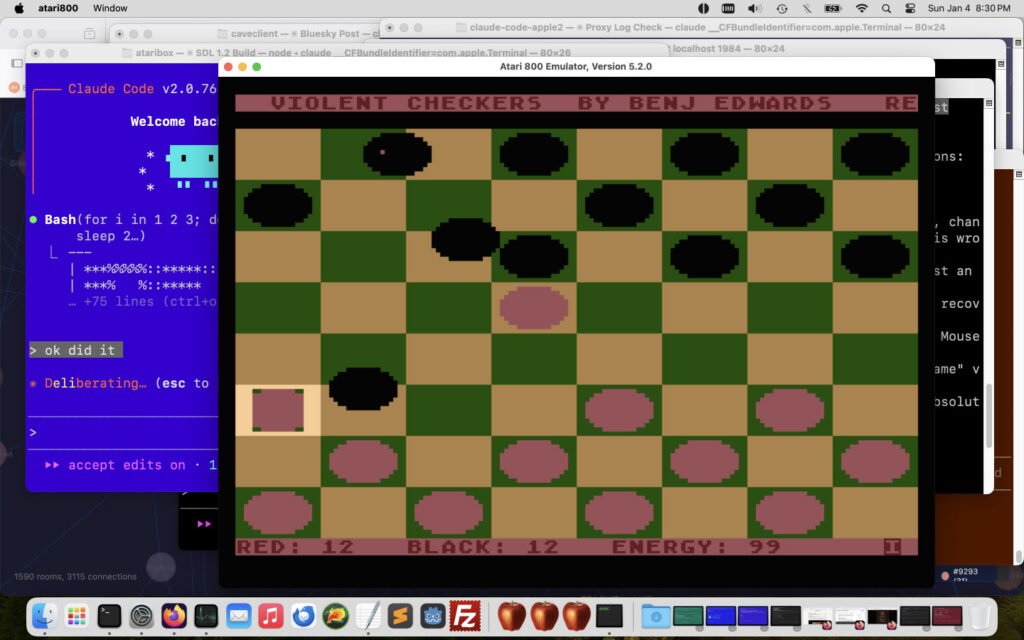

It took me five minutes to make a nice HTML5 demo with Claude but a week of torturous trial and error, plus actual systematic design on my part, to make a similar demo of an Atari 800 game. To do so, I had to use Claude Code to invent several tools, like command-line emulators and MCP servers, that allow it to peek into the operation of the Atari 800’s memory and chipset to even begin to make it happen.

3. True novelty can be an uphill battle

Due to what might poetically be called “preconceived notions” baked into a coding model’s neural network (more technically, statistical semantic associations), it can be difficult to get AI agents to create truly novel things, even if you carefully spell out what you want.

For example, I spent four days trying to get Claude Code to create an Atari 800 version of my HTML game Violent Checkers, but it had trouble because in the game’s design, the squares on the checkerboard don’t matter beyond their starting positions. No matter how many times I told the agent (and made notes in my Claude project files), it would come back to trying to center the pieces to the squares, snap them within squares, or use the squares as a logical basis of the game’s calculations when they should really just form a background image.

To get around this in the Atari 800 version, I started over and told Claude that I was creating a game with a UFO (instead of a circular checker piece) flying over a field of adjacent squares—never once mentioning the words “checker,” “checkerboard,” or “checkers.” With that approach, I got the results I wanted.

A screenshot of Benj’s Mac while working on a Violent Checkers port for the Atari 800 home computer, amid other projects. Credit: Benj Edwards

Why does this matter? Because with LLMs, context is everything, and in language, context changes meaning. Take the word “bank” and add the words “river” or “central” in front of it, and see how the meaning changes. In a way, words act as addresses that unlock the semantic relationships encoded in a neural network. So if you put “checkerboard” and “game” in the context, the model’s self-attention process links up a massive web of semantic associations about how checkers games should work, and that semantic baggage throws things off.

A couple of tricks can help AI coders navigate around these limitations. First, avoid contaminating the context with irrelevant information. Second, when the agent gets stuck, try this prompt: “What information do you need that would let you implement this perfectly right now? What tools are available to you that you could use to discover that information systematically without guessing?” This forces the agent to identify (semantically link up) its own knowledge gaps, spelled out in the context window and subject to future action, instead of flailing around blindly.

4. The 90 percent problem

The first 90 percent of an AI coding project comes in fast and amazes you. The last 10 percent involves tediously filling in the details through back-and-forth trial-and-error conversation with the agent. Tasks that require deeper insight or understanding than what the agent can provide still require humans to make the connections and guide it in the right direction. The limitations we discussed above can also cause your project to hit a brick wall.

From what I have observed over the years, larger LLMs can potentially make deeper contextual connections than smaller ones. They have more parameters (encoded data points), and those parameters are linked in more multidimensional ways, so they tend to have a deeper map of semantic relationships. As deep as those go, it seems that human brains still have an even deeper grasp of semantic connections and can make wild semantic jumps that LLMs tend not to.

Creativity, in this sense, may be when you jump from, say, basketball to how bubbles form in soap film and somehow make a useful connection that leads to a breakthrough. Instead, LLMs tend to follow conventional semantic paths that are more conservative and entirely guided by mapped-out relationships from the training data. That limits their creative potential unless the prompter unlocks it by guiding the LLM to make novel semantic connections. That takes skill and creativity on the part of the operator, which once again shows the role of LLMs as tools used by humans rather than independent thinking machines.

5. Feature creep becomes irresistible

While creating software with AI coding tools, the joy of experiencing novelty makes you want to keep adding interesting new features rather than fixing bugs or perfecting existing systems. And Claude (or Codex) is happy to oblige, churning away at new ideas that are easy to sketch out in a quick and pleasing demo (the 90 percent problem again) rather than polishing the code.

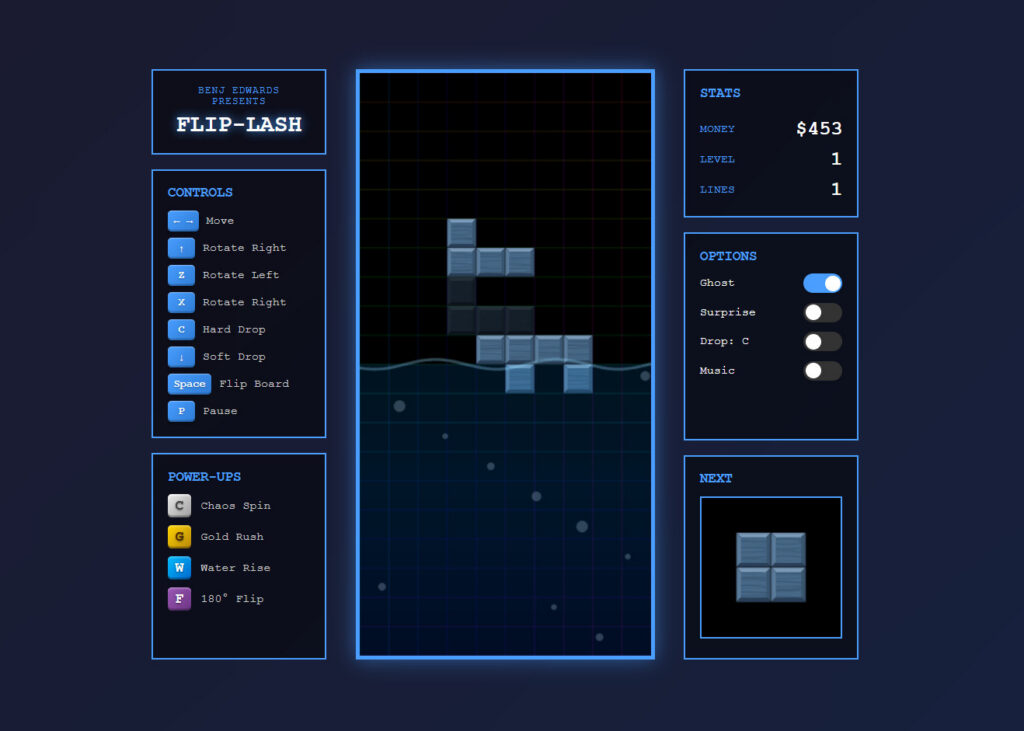

Flip-Lash started as a “Tetris but you can flip the board,” but feature creep made me throw in the kitchen sink, losing focus. Credit: Benj Edwards

Fixing bugs can also create bugs elsewhere. This is not new to coding agents—it’s a time-honored problem in software development. But agents supercharge this phenomenon because they can barrel through your code and make sweeping changes in pursuit of narrow-minded goals that affect lots of working systems. We’ve already talked about the importance of having a good architecture guided by the human mind behind the wheel above, and that comes into play here.

6. AGI is not here yet

Given the limitations I’ve described above, it’s very clear that an AI model with general intelligence—what people usually call artificial general intelligence (AGI)—is still not here. AGI would hypothetically be able to navigate around baked-in stereotype associations and not have to rely on explicit training or fine-tuning on many examples to get things right. AI companies will probably need a different architecture in the future.

I’m speculating, but AGI would likely need to learn permanently on the fly—as in modify its own neural network weights—instead of relying on what is called “in-context learning,” which only persists until the context fills up and gets compacted or wiped out.

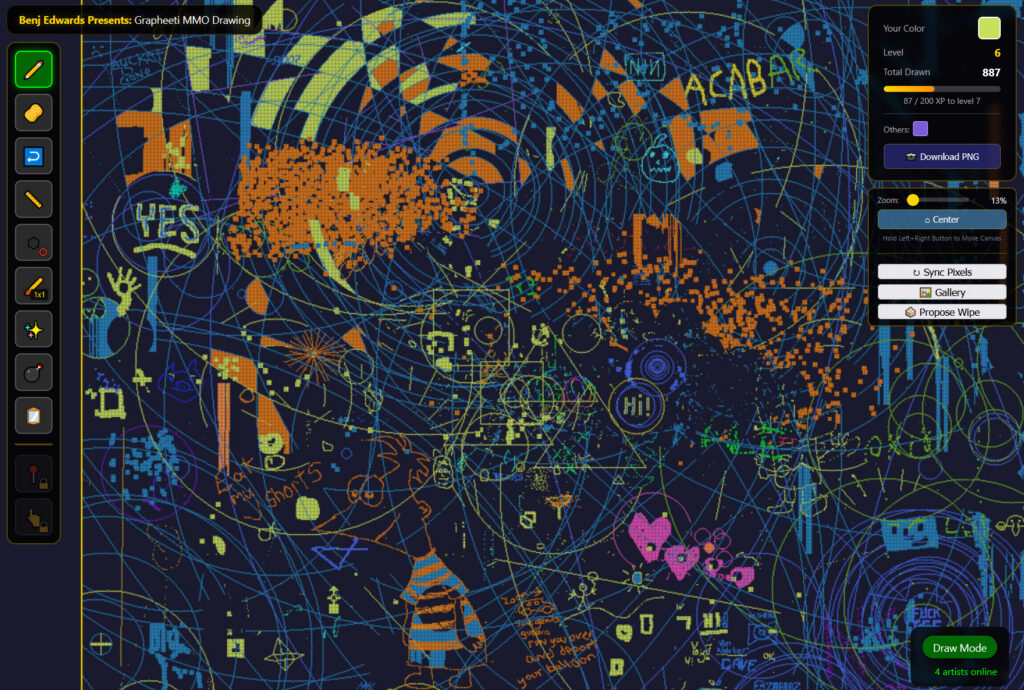

Grapheeti is a “drawing MMO” where people around the world share a canvas. Credit: Benj Edwards

In other words, you could teach a true AGI system how to do something by explanation or let it learn by doing, noting successes, and having those lessons permanently stick, no matter what is in the context window. Today’s coding agents can’t do that—they forget lessons from earlier in a long session or between sessions unless you manually document everything for them. My favorite trick is instructing them to write a long, detailed report on what happened when a bug is fixed. That way, you can point to the hard-earned solution the next time the amnestic AI model makes the same mistake.

7. Even fast isn’t fast enough

While using Claude Code for a while, it’s easy to take for granted that you suddenly have the power to create software without knowing certain programming languages. This is amazing at first, but you can quickly become frustrated that what is conventionally a very fast development process isn’t fast enough. Impatience at the coding machine sets in, and you start wanting more.

But even if you do know the programming languages being used, you don’t get a free pass. You still need to make key decisions about how the project will unfold. And when the agent gets stuck or makes a mess of things, your programming knowledge becomes essential for diagnosing what went wrong and steering it back on course.

8. People may become busier than ever

After guiding way too many hobby projects through Claude Code over the past two months, I’m starting to think that most people won’t become unemployed due to AI—they will become busier than ever. Power tools allow more work to be done in less time, and the economy will demand more productivity to match.

It’s almost too easy to make new software, in fact, and that can be exhausting. One project idea would lead to another, and I was soon spending eight hours a day during my winter vacation shepherding about 15 Claude Code projects at once. That’s too much split attention for good results, but the novelty of seeing my ideas come to life was addictive. In addition to the game ideas I’ve mentioned here, I made tools that scrape and search my past articles, a graphical MUD based on ZZT, a new type of MUSH (text game) that uses AI-generated rooms, a new type of Telnet display proxy, and a Claude Code client for the Apple II (more on that soon). I also put two AI-enabled emulators for Apple II and Atari 800 on GitHub. Phew.

Consider the advent of the steam shovel, which allowed humans to dig holes faster than a team using hand shovels. It made existing projects faster and new projects possible. But think about the human operator of the steam shovel. Suddenly, we had a tireless tool that could work 24 hours a day if fueled up and maintained properly, while the human piloting it would need to eat, sleep, and rest.

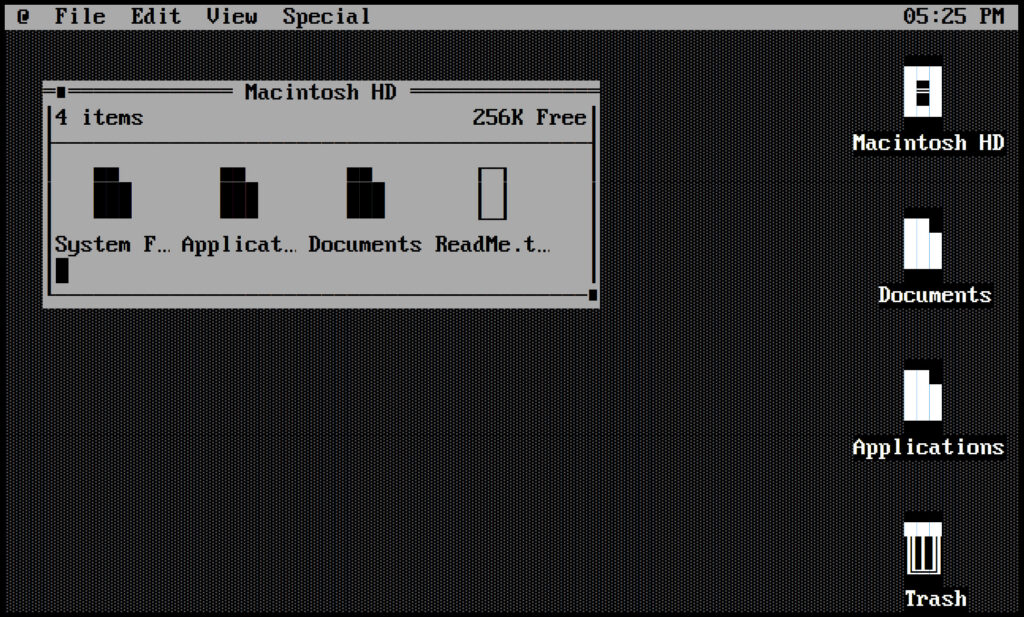

I used Claude Code to create a windowing GUI simulation of the Mac that works over Telnet. Credit: Benj Edwards

In fact, we may end up needing new protections for human knowledge workers using these tireless information engines to implement their ideas, much as unions rose as a response to industrial production lines over 100 years ago. Humans need rest, even when machines don’t.

Will an AI system ever replace the human role here? Even if AI coding agents could eventually work fully autonomously, I don’t think they’ll replace humans entirely because there will still be people who want to get things done, and new AI power tools will emerge to help them do it.

9. Fast is scary to people

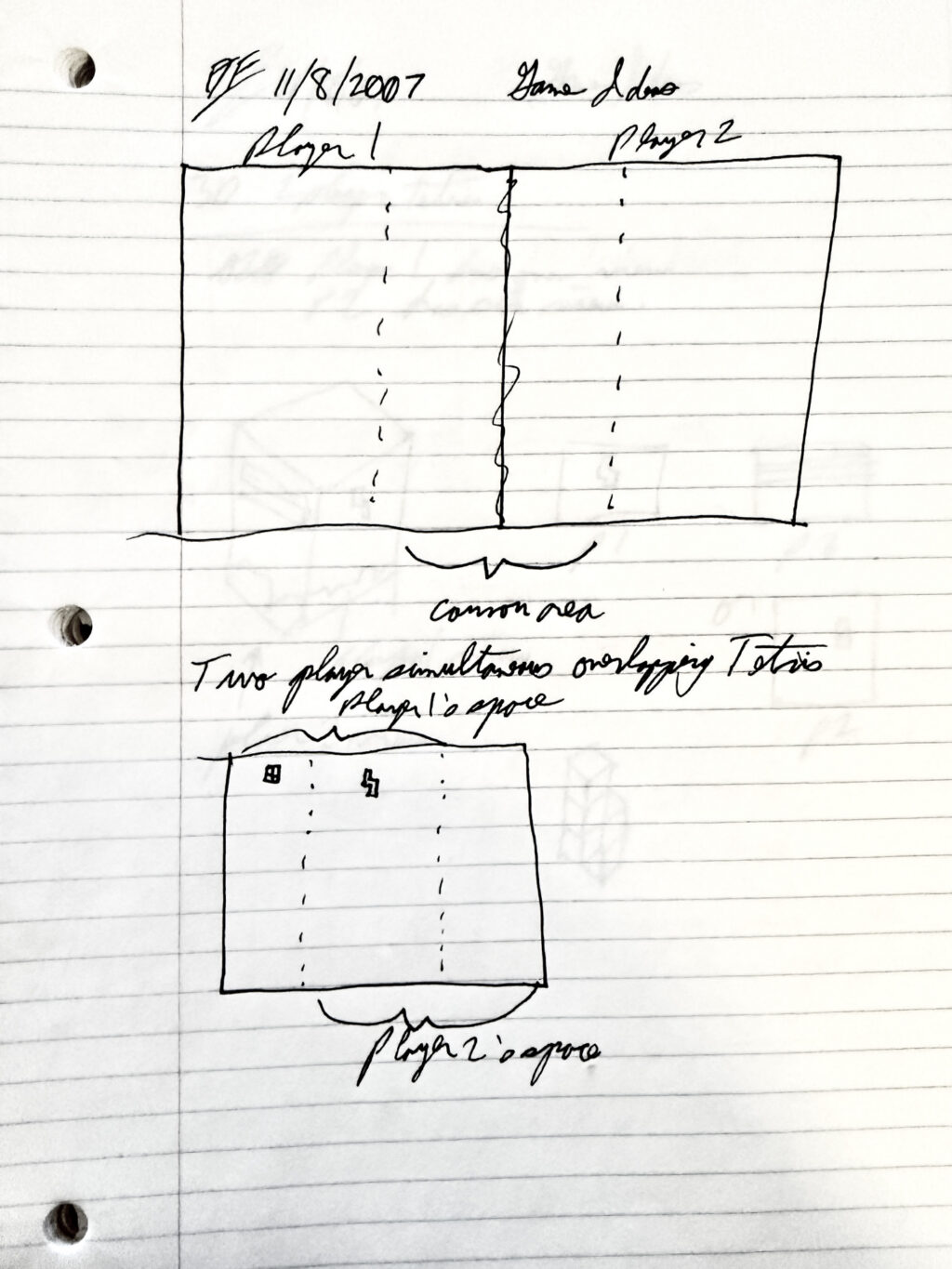

AI coding tools can turn what was once a year-long personal project into a five-minute session. I fed Claude Code a photo of a two-player Tetris game I sketched in a notebook back in 2008, and it produced a working prototype in minutes (prompt: “create a fully-featured web game with sound effects based on this diagram”). That’s wild, and even though the results are imperfect, it’s a bit frightening to comprehend what kind of sea change in software development this might entail.

Since early December, I’ve been posting some of my more amusing experimental AI-coded projects to Bluesky for people to try out, but I discovered I needed to deliberately slow down with updates because they came too fast for people to absorb (and too fast for me to fully test). I’ve also received comments like “I’m worried you’re using AI, you’re making games too fast” and so on.

Benj’s handwritten game design note about a two-player Tetris concept from 2007. Credit: Benj Edwards

Regardless of my own habits, the flow of new software will not slow down. There will soon be a seemingly endless supply of AI-augmented media (games, movies, images, books), and that’s a problem we’ll have to figure out how to deal with. These products won’t all be “AI slop,” either; some will be done very well, and the acceleration in production times due to these new power tools will balloon the quantity beyond anything we’ve seen.

Social media tends to prime people to believe that AI is all good or all bad, but that kind of black-and-white thinking may be the easy way out. You’ll have no cognitive dissonance, but you’ll miss a far richer third option: seeing these tools as imperfect and deserving of critique but also as useful and empowering when they bring your ideas to life.

AI agents should be considered tools, not entities or employees, and they should be amplifiers of human ideas. My game-in-progress Card Miner is entirely my own high-level creative design work, but the AI model handled the low-level code. I am still proud of it as an expression of my personal ideas, and it would not exist without AI coding agents.

10. These tools aren’t going away

For now, at least, coding agents remain very much tools in the hands of people who want to build things. The question is whether humans will learn to wield these new tools effectively to empower themselves. Based on two months of intensive experimentation, I’d say the answer is a qualified yes, with plenty of caveats.

We also have social issues to face: Professional developers already use these tools, and with the prevailing stigma against AI tools in some online communities, many software developers and the platforms that host their work will face difficult decisions.

Ultimately, I don’t think AI tools will make human software designers obsolete. Instead, they may well help those designers become more capable. This isn’t new, of course; tools of every kind have been serving this role since long before the dawn of recorded history. The best tools amplify human capability while keeping a person behind the wheel. The 3D printer analogy holds: amazing fast results are possible, but mastery still takes time, skill, and a lot of patience with the machine.

10 things I learned from burning myself out with AI coding agents Read More »