RFK Jr.’s new CDC deputy director prefers “natural immunity” over vaccines

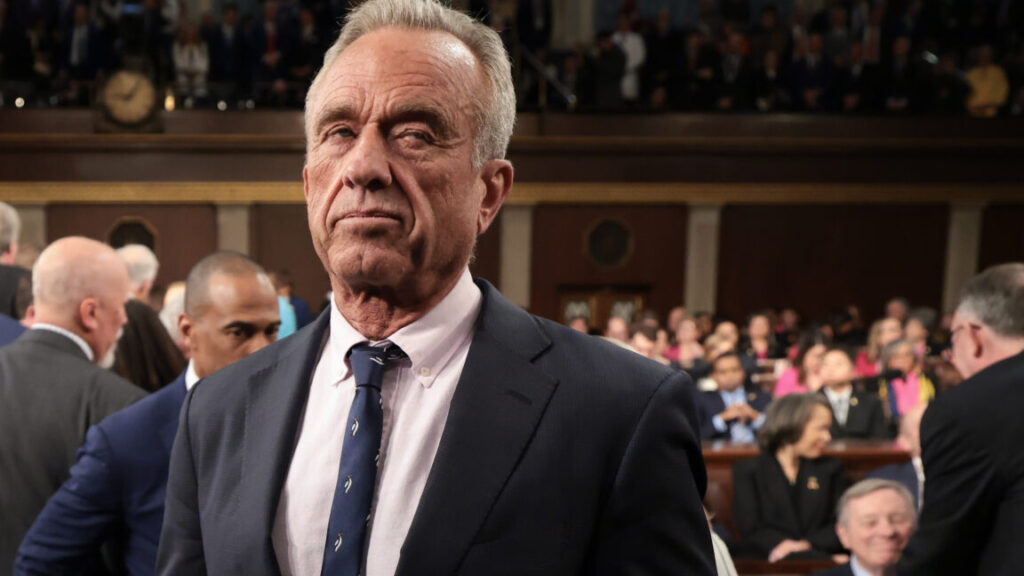

Under ardent anti-vaccine Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has named Louisiana Surgeon General Ralph Abraham as its new principal deputy director—a choice that was immediately called “dangerous” and “irresponsible,” yet not as bad as it could have been, by experts.

Physician Jeremy Faust revealed the appointment in his newsletter Inside Medicine yesterday, which was subsequently confirmed by journalists. Faust noted that a CDC source told him, “I heard way worse names floated,” and although Abraham’s views are “probably pretty terrible,” he at least has had relevant experience running a public health system, unlike other current leaders of the agency.

But Abraham hasn’t exactly been running a health system the way most public health experts would recommend. Under Abraham’s leadership, the Louisiana health department waited months to inform residents about a deadly whooping cough (pertussis) outbreak. He also has a clear record of anti-vaccine views. Earlier this year, he told a Louisiana news outlet he doesn’t recommend COVID-19 vaccines because “I prefer natural immunity.” In February, he ordered the health department to stop promoting mass vaccinations, including flu shots, and barred staff from running seasonal vaccine campaigns.

RFK Jr.’s new CDC deputy director prefers “natural immunity” over vaccines Read More »