Radioactive drugs strike cancer with precision

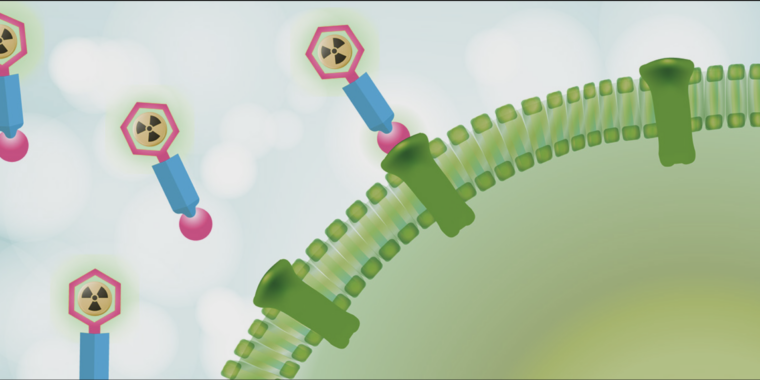

Enlarge / Pharma interest and investment in radiotherapy drugs is heating up.

Knowable Magazine

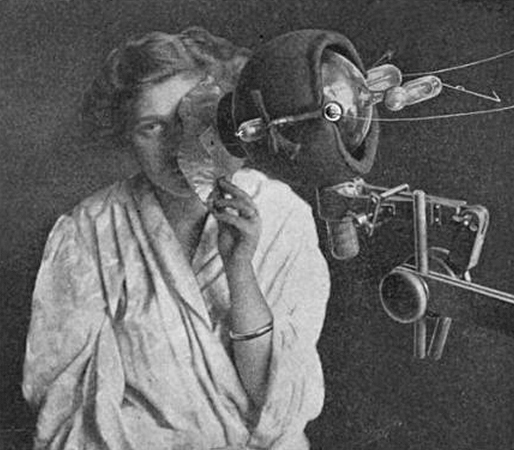

On a Wednesday morning in late January 1896 at a small light bulb factory in Chicago, a middle-aged woman named Rose Lee found herself at the heart of a groundbreaking medical endeavor. With an X-ray tube positioned above the tumor in her left breast, Lee was treated with a torrent of high-energy particles that penetrated into the malignant mass.

“And so,” as her treating clinician later wrote, “without the blaring of trumpets or the beating of drums, X-ray therapy was born.”

Radiation therapy has come a long way since those early beginnings. The discovery of radium and other radioactive metals opened the doors to administering higher doses of radiation to target cancers located deeper within the body. The introduction of proton therapy later made it possible to precisely guide radiation beams to tumors, thus reducing damage to surrounding healthy tissues—a degree of accuracy that was further refined through improvements in medical physics, computer technologies and state-of-the-art imaging techniques.

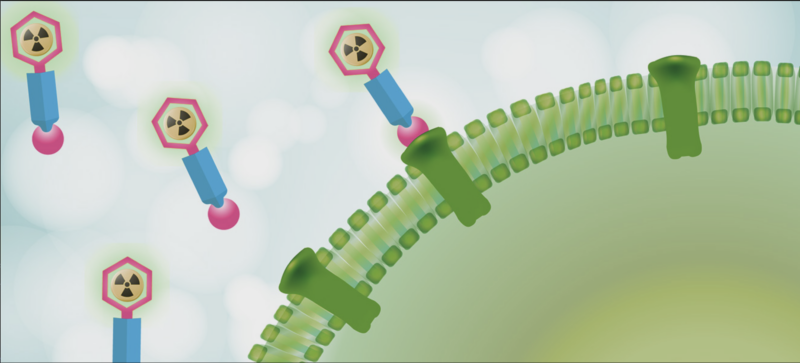

But it wasn’t until the new millennium, with the arrival of targeted radiopharmaceuticals, that the field achieved a new level of molecular precision. These agents, akin to heat-seeking missiles programmed to hunt down cancer, journey through the bloodstream to deliver their radioactive warheads directly at the tumor site.

Use of radiation to kill cancer cells has a long history. In this 1915 photo, a woman receives “roentgenotherapy”—treatment with X-rays—directed at an epithelial-cell cancer on her face.

Wikimedia Commons

Today, only a handful of these therapies are commercially available for patients—specifically, for forms of prostate cancer and for tumors originating within hormone-producing cells of the pancreas and gastrointestinal tract. But this number is poised to grow as major players in the biopharmaceutical industry begin to invest heavily in the technology.

AstraZeneca became the latest heavyweight to join the field when, on June 4, the company completed its purchase of Fusion Pharmaceuticals, maker of next-generation radiopharmaceuticals, in a deal worth up to $2.4 billion. The move follows similar billion-dollar-plus transactions made in recent months by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) and Eli Lilly, along with earlier takeovers of innovative radiopharmaceutical firms by Novartis, which continued its acquisition streak—begun in 2018—with another planned $1 billion upfront payment for a radiopharma startup, as revealed in May.

“It’s incredible how, suddenly, it’s all the rage,” says George Sgouros, a radiological physicist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and the founder of Rapid, a Baltimore-based company that provides software and imaging services to support radiopharmaceutical drug development. This surge in interest, he points out, underscores a wider recognition that radiopharmaceuticals offer “a fundamentally different way of treating cancer.”

Treating cancer differently, however, means navigating a minefield of unique challenges, particularly in the manufacturing and meticulously timed distribution of these new therapies, before the radioactivity decays. Expanding the reach of the therapy to treat a broader array of cancers will also require harnessing new kinds of tumor-killing particles and finding additional suitable targets.

“There’s a lot of potential here,” says David Nierengarten, an analyst who covers the radiopharmaceutical space for Wedbush Securities in San Francisco. But, he adds, “There’s still a lot of room for improvement.”

Atomic advances

For decades, a radioactive form of iodine stood as the sole radiopharmaceutical available on the market. Once ingested, this iodine gets taken up by the thyroid, where it helps to destroy cancerous cells of that butterfly-shaped gland in the neck—a treatment technique established in the 1940s that remains in common use today.

But the targeted nature of this strategy is not widely applicable to other tumor types.

The thyroid is naturally inclined to absorb iodine from the bloodstream since this mineral, which is found in its nonradioactive form in many foods, is required for the synthesis of certain hormones made by the gland.

Other cancers don’t have a comparable affinity for radioactive elements. So instead of hijacking natural physiological pathways, researchers have had to design drugs that are capable of recognizing and latching onto specific proteins made by tumor cells. These drugs are then further engineered to act as targeted carriers, delivering radioactive isotopes—unstable atoms that emit nuclear energy—straight to the malignant site.

Radioactive drugs strike cancer with precision Read More »