Ars Technica’s Top 20 video games of 2025

When we put together our top 20 games of last year, we specifically called out Civilization 7, Avowed, Doom: The Dark Ages, and Grand Theft Auto 6 as big franchise games we were already looking forward to for 2025. While one of those games has been delayed into 2026, the three others made this year’s list of Ars’ favorite games as expected. They join a handful of other highly anticipated sequels, ranging from big-budget blockbusters to long-gestating indies, on the “expected” side of this year’s list.

But the games that really stood out for me in 2025 were the ones that seemed to come out of nowhere. Those range from hard-to-categorize roguelike puzzle games to a gonzo, punishing mountainous walking simulation, the best Geometry Wars clone in years, and a touching look at the difficulties of adolescence through the surprisingly effective lens of mini-games.

As we look toward 2026, there are plenty of other big-budget projects that the industry is busy preparing for (the delayed Grand Theft Auto VI chief among them). If next year is anything like this year, though, we can look forward to plenty more games that no one saw coming suddenly vaulting into view as new classics.

Assassin’s Creed Shadows

Ubisoft Quebec; Windows, MaxOS, PS5, Xbox Series X|S, Switch 2, iPad

When I was younger, I wanted—and expected—virtually every game I played to blow me away with something I’d not seen before. It was easier to hit that bar in the ’90s, when both the design and technology of games were moving at an incredible pace.

Now, as someone who still games in his 40s, I’m excited to see that when it happens, but I don’t expect it, Now, I increasingly appreciate games that act as a sort of comfort food, and I value some games as much for their familiarity as I do their originality.

That’s what Assassin’s Creed Shadows is all about (as I wrote when it first came out). It follows a well-trodden formula, but it’s a beautifully polished version of that formula. Its world is grand and escapist, its audio and graphics presentation is immersive, and it makes room for many different playstyles and skill levels.

If your idea of a good time is “be a badass, but don’t think too hard about it,” Shadows is one of the best Assassin’s Creed titles in the franchise’s long history. It doesn’t reinvent any wheels, but after nearly two decades of Assassin’s Creed, it doesn’t really need to; the new setting and story are enough to separate it, while the gameplay remains familiar.

-Samuel Axon

Avowed

Obsidian Entertainment; Windows, Xbox Series X|S

No game this year has made me feel as hated as Avowed. As an envoy for the far-off Aedryan empire, your role in Avowed is basically to be hated, either overtly or subtly, by almost everyone you encounter in the wild, semi-colonized world of the Living Lands. The low-level hum of hatred and mistrust from the citizens permeates everything you do in the game, which is an unsettling feeling in a genre usually characterized by the moral certitude of heroes fighting world-ending evil.

Role-playing aside, Avowed is helpfully carried by its strong action-packed combat system, characterized as it is by thrilling moment-to-moment positional jockeying and the juggling of magic spells, ranged weapons, and powerful close-range melee attacks. The game’s quest system also does a good job of letting players balance this combat difficulty for themselves—if a goal is listed with three skull symbols on your menu, you’d best put it off until you’ve leveled up a little bit more.

I can take or leave the mystical mumbo-jumbo-filled subplot surrounding your status as a “godlike” being that can converse with spirits. Aside from that, though, I’ve never had so much fun being hated.

-Kyle Orland

Baby Steps

Gabe Cuzzillo, Maxi Boch, Bennett Foddy; Windows, PS5

The term “walking simulator” often gets thrown around in some game criticism circles as a derisive term for a title that’s about nothing more than walking around and looking at stuff. While Baby Steps might technically fit into that “walking simulator” model, stereotyping it in that way does this incredibly inventive game a disservice.

It starts with the walking itself, which requires meticulous, rhythmic manipulation of both shoulder buttons and both analog sticks just to stay upright. Super Mario 64, this ain’t. But what starts as a struggle to take just a few short steps quickly becomes almost habitual, much like learning to walk in real life.

The game then starts throwing new challenges at your feet. Slippery surfaces. Narrow stairways with tiny footholds. Overhangs that block your ridiculously useless, floppy upper body. The game’s relentless mountain is designed such that a single missed step can ruin huge chunks of progress, in the proud tradition of Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy.

This all might sound needlessly cruel and frustrating, but trust me, it’s worth sticking with to the end. That’s in part for the feeling of accomplishment when you do finally make it past that latest seemingly impossible wall, and partly to experience an absolutely gonzo story that deals directly and effectively with ideas of masculinity, perseverance, and society itself. You’ll never be so glad to take that final step.

-Kyle Orland

Ball x Pit

Kenny Sun; Windows, MacOS, PS5, Xbox Series X|S, Switch, Switch 2

The idea of bouncing a ball against a block is one of the most tried-and-true in all of gaming, from the basic version in the ancient Breakout to the number-filled angles of Holedown. But perhaps no game has made this basic concept as compulsively addictive as Ball x Pit.

Here, the brick-breaking genre is crossed with the almost as storied shoot-em-up, with the balls serving as your weapons and the blocks as enemies that march slowly but relentlessly from the top of the screen to the bottom. The key to destroying those blocks all in time is bouncing your growing arsenal of new balls at just the right angles to maximize their damage-dealing impact and catching them again so you can throw them once more that much faster.

Like so many roguelikes before it, Ball x Pit uses randomization as the core of its compulsive loop, letting you choose from a wide selection of new abilities and ball-based attacks as you slowly level up. But Ball x Pit goes further than most in letting you fuse and combine those balls into unique combinations that take dozens of runs to fully uncover and combine effectively.

Add in a deep system of semi-permanent upgrades (with its own intriguing “bounce balls around a city builder” mini game) and a deep range of more difficult settings and enemies to slowly unlock, and you have a game whose addictive pull will last much longer than you might expect from the simple premise.

-Kyle Orland

Blue Prince

Dogubomb; Windows, MacOS, PS5, Xbox Series X|S

Usually, when formulating a list like this, you can compare a title to an existing game or genre as a shorthand to explain what’s going on to newcomers. That’s nearly impossible with Blue Prince, a game that combines a lot of concepts to defy easy comparison to games that have come before it.

At its core, Blue Prince is about solving the mysteries of a house that you build while exploring it, drafting the next room from a selection of three options every time you open a new door. Your initial goal, if you can call it that, is to discover and access the mysterious “Room 46” that apparently exists somewhere on the 45-room grid. And while the houseplan you’re building resets with every in-game day, the knowledge you gain from exploring those rooms stays with you, letting you make incremental progress on a wide variety of puzzles and mysteries as you rebuild the mansion from scratch again and again.

What starts as a few simple and relatively straightforward puzzles quickly unfolds fractally into a complex constellation of conundrums, revealed slowly through scraps of paper, in-game books, inventory items, interactive machinery, and incidental background elements. Figuring out the more intricate mysteries of the mansion requires careful observation and, often, filling a real-life mad scientist’s notepad with detailed notes that look incomprehensible to an outsider. All the while, you have to manage each day’s limited resources and luck-of-the-draw room drafting to simply find the right rooms to make the requisite progress.

Getting to that storied Room 46 is enough to roll the credits on Blue Prince, and it serves as an engaging enough puzzle adventure in its own right. But that whole process could be considered a mere tutorial for a simply massive endgame, which is full of riddles that will perplex even the most experienced puzzlers while slowly building a surprisingly deep story of political intrigue and spycraft through some masterful environmental storytelling.

Some of those extreme late-game puzzles might be too arcane for their own good, honestly, and will send many players scrambling for a convenient guide or wiki for some hints. But even after playing for over 100 hours over two playthroughs, I’m pretty sure I’m still not done exploring all that Blue Prince has to offer.

-Kyle Orland

Civilization VII

Firaxis; Windows, MacOS, Linux, PS4/5, Xbox One/Series X|S, Switch 2

This one will be controversial: I love Civilization VII.

Civilization VII launched as a bit of a mess. There were bugs and UI shortcomings aplenty. Most (but not all) of those have been addressed in the months since, but they’re not the main reason this is a tricky pick.

The studio behind the Civilization franchise, Firaxis, has long said it has a “33/33/33″ approach to sequels in the series, wherein 33 percent of the game should be familiar systems, 33 percent should be remixes or improvements of familiar systems, and 33 percent should be entirely new systems.

Critics of Civilization VII say Firaxis broke that 33/33/33 rule by overweighting the last 33 percent, mainly to chase innovations in the 4X genre by other games (like Humankind). I don’t disagree, but I also welcome it.

Credit is due to the team at Firaxis for ingeniously solving some longstanding design problems in the franchise, like using the new age transitions to curb snowballing and to expunge systems that become a lot less fun in the late game than they are in the beginning. Judged on its own terms, Civilization VII is a deep, addictive, and fun strategy game that I’ve spent more than 100 hours playing this year.

My favorite Civ game remains Civilization IV, but that game still runs fine on modern systems, is infinitely replayable out of the box, and enjoys robust modding support. I simply didn’t need more of the same from this particular franchise; to me, VII coexists with IV and others on my hard drive—very different flavors of the same idea.

-Samuel Axon

CloverPit

Panik Arcade; Windows, Xbox Series X|S

I’m not sure I like what my minor CloverPit obsession says about me. When I fell into a deep Balatro hole last year, I could at least delude myself into thinking there was some level of skill in deciding which jokers to buy and sell, which cards to add or prune from my deck, and which cards to hold and discard. In the end, though, I was as beholden to the gods of random number generation as any other Balatro player.

Cloverpit makes the surrender to the vagaries of luck all the more apparent, replacing the video-poker-like systems of Balatro with a “dumb” slot machine whose handle you’re forced to pull over and over again. Sure, there are still decisions to make, mostly regarding which lucky charms you purchase from a vending machine on the other side of the room. And there is some skill involved in learning and exploiting lucky charm synergies to extract the highest expected value from those slot machine pulls.

Once you’ve figured out those basic strategies, though, CloverPit mostly devolves into a series of rerolls waiting for the right items to show up in the shop in the right order. Thankfully, the game hides plenty of arcane secrets beneath its charming PS1-style spooky-horror presentation, slowly revealing new items and abilities that hint that something deeper than just accumulating money might be the game’s true end goal.

It’s this creepy vibe and these slowly unfolding secrets that have compelled me to pour dozens of hours into what is, in the end, just a fancy slot machine simulator. God help me.

-Kyle Orland

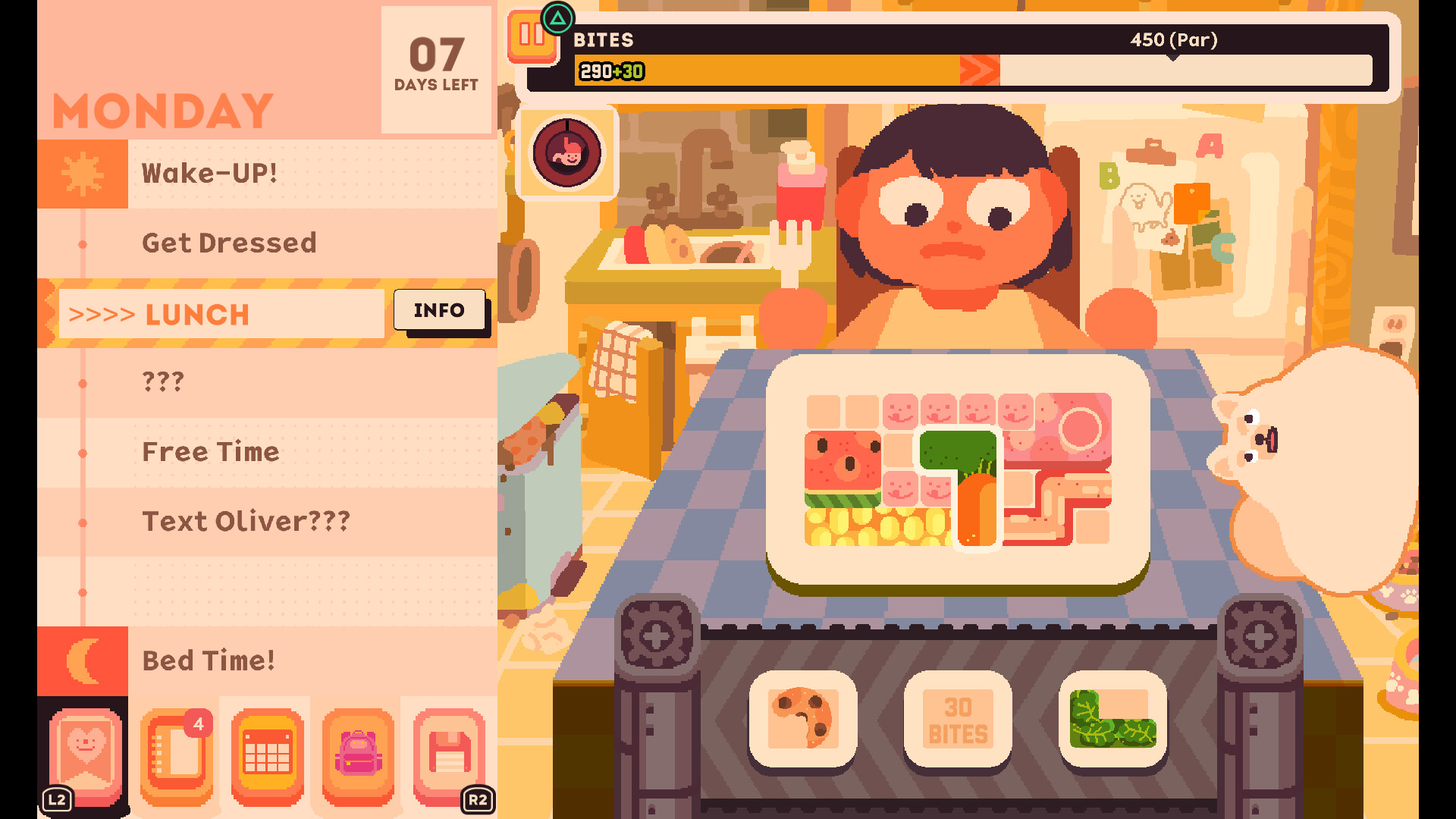

Consume Me

Jenny Jiao Hsia, AP Thomson; Windows, MacOS

Jenny is your average suburban Asian-American teenager, struggling to balance academic achievement, chores, an overbearing mother, romantic entanglements, and a healthy body image. What sounds like the premise for a cliché young adult novel actually serves to set up a compelling interactive narrative disguised as a mere mini-game collection.

Consume Me brilliantly integrates the conflicting demands placed on Jenny’s time and attention into the gameplay itself. Creating a balanced meal, for instance, becomes a literal test of balancing vaguely Tetris-shaped pieces of food on a tray, satisfying your hunger and caloric limits at the same time. Chores take up time but give you money you can spend on energy drinks that let you squeeze in more activities by staying up late (but can lead to debilitating headaches). A closet full of outfits becomes an array of power-ups to your time, energy, or focus.

It takes almost preternatural resource management skills and mini-game execution to satisfy all the expectations being placed on you, which is kind of the meta-narrative point. No matter how well you do, Jenny’s story develops in a way that serves as a touching semi-autobiographical look at the life of co-creator Jenny Jiao Hsia. That biography is made all the more sympathetic here for an interactive presentation that’s more engaging than any young adult novel could be.

-Kyle Orland

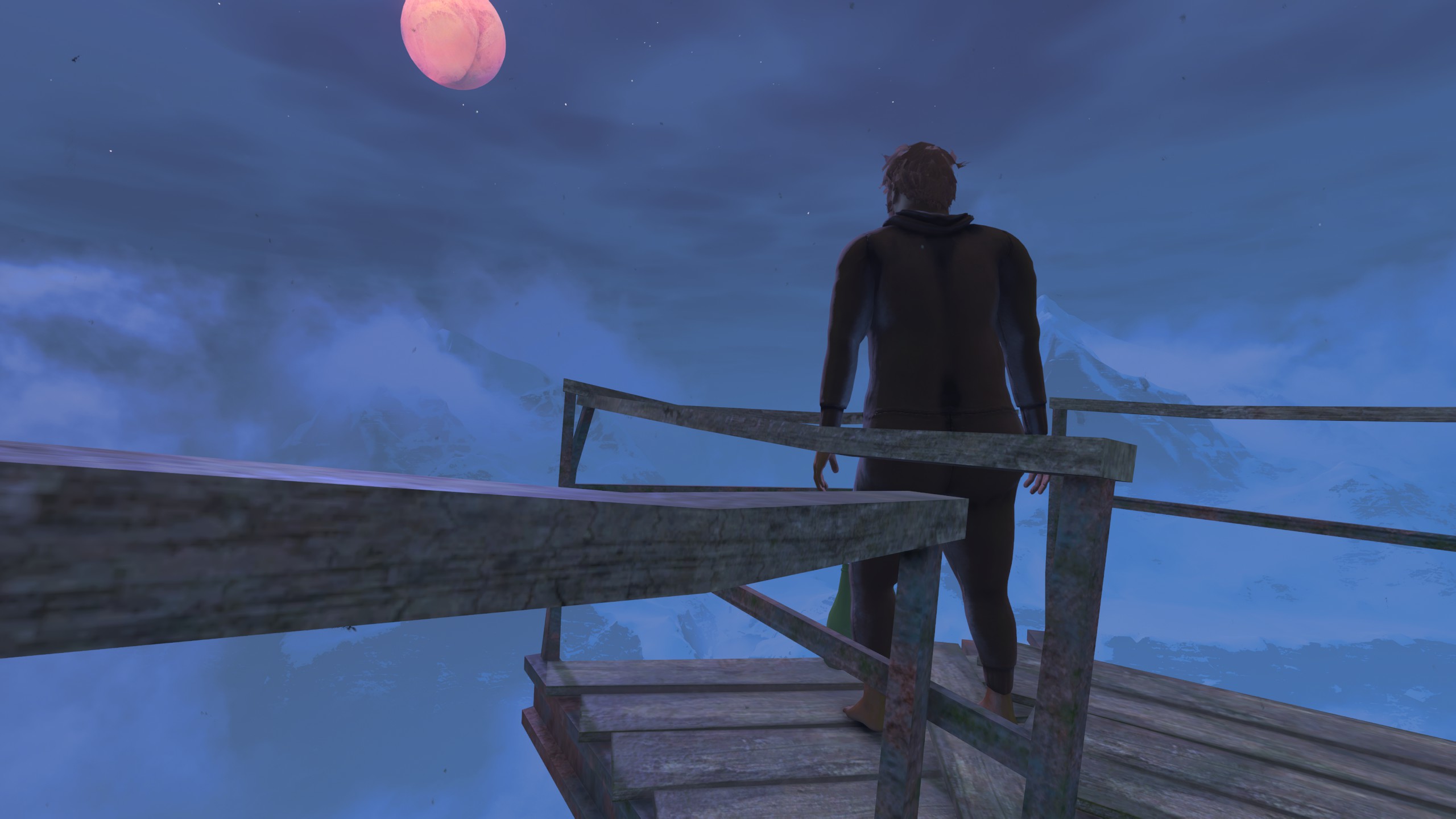

Death Stranding 2: On the Beach

Kojima Productions; PS5

Death Stranding 2: On the Beach should not be fun. Much like its predecessor, the latest release from famed game designer Hideo Kojima is about delivering packages—at least on the surface. Yet the process of planning your routes, managing inventory, and exploring an unfathomably strange post-apocalyptic world remains a winning formula.

The game again follows Sam Porter Bridges (played by Norman Reedus) on his quest to reconnect the world as humanity faces possible extinction. And yes, that means acting like a post-apocalyptic Amazon Prime. Standing in the way of an on-time delivery are violent raiders, dangerous terrain, and angry, disembodied spirits known as Beached Things.

It’s common to hear Death Stranding described as a walking simulator, and there is indeed a lot of walking, but the sequel introduces numerous quality-of-life improvements that make it more approachable. Death Stranding 2 has a robust fast-travel mechanic and better vehicles to save you from unnecessary marches, and the inventory management system is less clunky. That’s important in a game that asks you to traverse an entire continent to deliver cargo.

Beyond the core gameplay loop of stacking heavy boxes on your back, Death Stranding 2 has all the Kojima vibes you could want. There are plenty of quirky gameplay mechanics and long cutscenes that add depth to the characters and keep the story moving. The world of Death Stranding has been designed from the ground up around the designer’s flights of fancy, and it works—even the really weird stuff almost makes sense!

Along the way, Death Stranding 2 has a lot to say about grief, healing, and the value of human connection. The game’s most poignant cutscenes are made all the more memorable by an incredible soundtrack, and we cannot oversell the strength of the mocap performances.

It may take 100 hours or more to experience everything the game has to offer, but it’s well worth your time.

-Ryan Whitwam

Donkey Kong Bananza

Nintendo EPD; Switch 2

Credit: Nintendo

Since the days of Donkey Kong Country, I’ve always felt that Mario’s original ape antagonist wasn’t really up for anchoring a Mario-level platform franchise. Donkey Kong Bananza is the first game to really make me doubt that take.

Bonanza is a great showcase for the new, more powerful hardware on the Switch 2, with endlessly destructible environments that send some impressive-looking shiny shrapnel flying when they’re torn apart. It can’t be understated how cathartic it is to pound tunnels up, down, and through pretty much every floor, ceiling, and wall you see, mashing the world itself to suit your needs.

Bonanza also does a good job aping Super Mario Odyssey’s tendency to fill practically every square inch of space with collectible doodads and a wide variety of challenges. This is not a game where you need to spend a lot of time aimlessly wandering for the next thing to do—there’s pretty much always something interesting around the next corner until the extreme end game.

Sure, the camera angles and frame rate might suffer a bit during the more chaotic bits. But it’s hard to care when you’re having this much fun just punching your way through Bananza’s imaginative, colorful, and malleable world.

-Kyle Orland

Doom: The Dark Ages

Id Software; Windows, PS5, Xbox Series X|S

Credit: Bethesda Game Studios

For a series that has always been about dodging, Doom: The Dark Ages is much more about standing your ground. The game’s key verbs involve raising your shield to block incoming attacks or, ideally, parrying them back in the direction they came.

It’s a real “zig instead of zag” moment for the storied Doom series, and it does take some getting used to. Overall, though, I had a great time mixing in turtle-style blocking with the habitual pattern of circling-strafing around huge groups of enemies in massive arenas and quickly switching between multiple weapons to deal with them as efficiently as possible. While I missed the focus on extreme verticality of the last two Doom games, I appreciate the new game’s more open-world design, which gives completionist players a good excuse to explore every square inch of these massive environments for extra challenges and hidden collectibles.

The only real problem with Doom: The Dark Ages comes when the game occasionally transitions to a slow-paced mech-style demon battle or awkward flying dragon section, sometimes for entire levels at a time. Those variations aside, I came away very satisfied with the minor change in focus for a storied shooter series.

-Kyle Orland

Dragonsweeper

Daniel Benmergui; Javascript

Anyone who has read my book-length treatise on Minesweeper knows I’m a sucker for games that involve hidden threats within a grid of revealed numbers. But not all variations on this theme are created equal. Dragonsweeper stands out from the crowd by incorporating a simple but arcane world of RPG-style enemies and items into its logical puzzles.

Instead of simply counting the number of nearby mines, each number revealed on the Dragonsweeper grid reflects the total health of the surrounding enemies, both seen and unseen. Attacking those enemies means enduring predictable counterattacks that deplete your limited health bar, which you can grow through gradual leveling until you’re strong enough to kill the game’s titular dragon, taunting you from the center of the field.

Altogether, it adds an intriguing new layer to the logical deduction, forcing you to carefully manage your moves to maximize the impact of your attacks and the limited health-restoring items scattered throughout the field. And while finishing one run isn’t too much of a challenge, completing the game’s optional achievements and putting together a “perfect” game score is enough to keep puzzle lovers coming back for hours and hours of compelling logical deduction.

-Kyle Orland

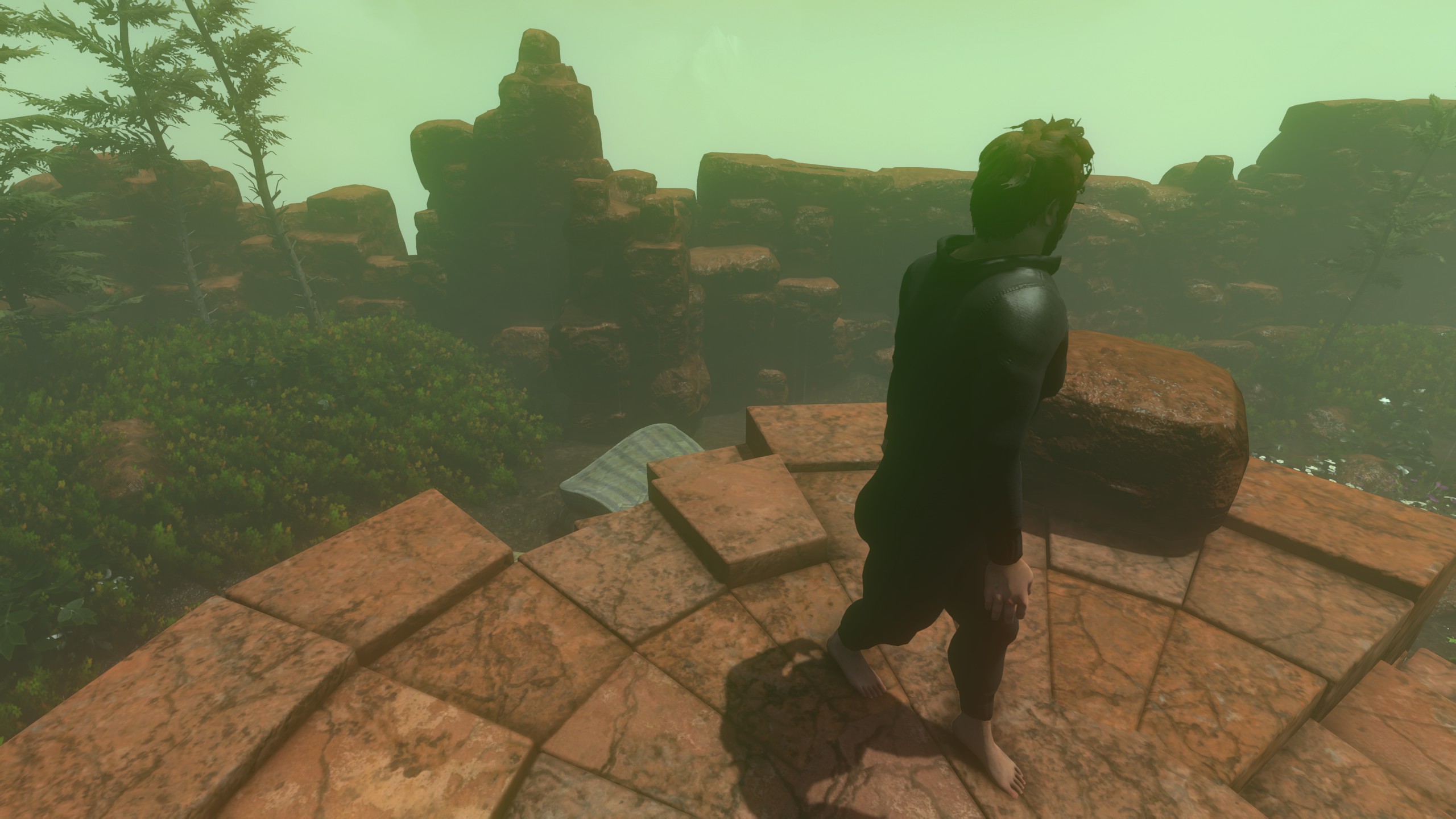

Elden Ring: Nightreign

FromSoftware; Windows, PS4/5, Xbox One/Series X|S

Credit: Bandai Namco

At first blush, Nightreign feels like a twisted perversion of everything that has made FromSoft’s Souls series so compelling for so many years. What was a slow-paced, deliberate open-world RPG has become a game about quickly sprinting across a quickly contracting map, leveling up as quickly as possible before taking on punishing bosses. A moody solitary experience has become one that practically requires a group of three players working together. It’s like an Elden Ring-themed amusement park that seems to miss the point of the original.

Whatever. It still works!

Let the purists belly ache about how it’s not really Elden Ring. They’re right, but they’re missing the point. Nightreign condenses the general vibe of the Elden Ring world into something very different but no less enjoyable. What’s more, it packs that vibe into a tight experience that can be easily squeezed into a 45-minute sprint rather than requiring dozens of hours of deep exploration.

That makes it the perfect excuse to get together with a few like-minded Elden Ring-loving friends, throw on a headset, and just tear through the Lands Between together for the better part of an evening. As Elden Ring theme parks go, you could do a lot worse.

-Kyle Orland

Ghost of Yotei

Sucker Punch Productions; PS5

Ghost of Yotei from Sucker Punch Productions starts as a revenge tale, featuring hard-as-nails Atsu on the hunt for the outlaws who murdered her family. While there is plenty of revenge to be had in the lands surrounding Mount Yotei, the people Atsu meets and the stories they have to tell make this more than a two-dimensional quest for blood.

The game takes place on the northern Japanese island of Ezo (modern-day Hokkaido) several centuries after the developer’s last samurai game, Ghost of Tsushima. It has a lot in common with that title, but Ghost of Yotei was built for the PS5 and features a massive explorable world and stunning visuals. It’s easy to get sidetracked from your quest just exploring Ezo and tinkering with the game’s photo mode.

The land of Ezo avoids some of the missteps seen in other open-world games. While it’s expansive and rich with points of interest, exploring it is not tedious. There are no vacuous fetch quests or mindless collecting (or loading screens, for that matter). Even when you think you know what you’re going to find at a location, you may be surprised. The interesting side quests and random encounters compel you to keep exploring Ezo.

Ghost of Yotei’s combat is just as razor-sharp as its exploration. It features multiple weapon types, each with unlockable abilities and affinities that make them ideal for taking on certain foes. Brute force will only get you so far, though. You need quick reactions to parry enemy attacks and strike back—it’s challenging and rewarding but not frustrating.

It’s impossible to play Ghost of Yotei without becoming invested in the journey, and a big part of that is thanks to the phenomenal voice work of Erika Ishii as Atsu. Some of the game’s pivotal moments will haunt you, but luckily, the developer has just added a New Game+ mode so you can relive them all again.

-Ryan Whitwam

Hades 2

Supergiant Games; Windows, MacOS, Switch, Switch 2

There’s a moment in the second section of Hades 2 where you start to hear a haunting melody floating through the background. That music gets louder and louder until you reach the game’s second major boss, a trio of sirens that go through a full rock-opera showtune number as you dodge their bullet-hell attacks and look for openings to go in for the kill. That three-part musical presentation slowly dwindles to a solo as you finally dispatch the sirens one by one, restoring a surprisingly melancholy silence once more.

It’s this and other musical moments casually and effortlessly woven through Hades 2 that will stick with me the most. But the game stands on its own beyond the musicality, expanding the original game’s roguelike action with a compelling new spell system that lets you briefly capture or slow enemies in a binding circle. This small addition adds a new sense of depth to the moment-to-moment positional dance that was already so compelling in the original Hades.

Hades 2 also benefits greatly from the introduction of Melinoe, a compelling new protagonist who gets fleshed out through her relationship with the usual rogue’s gallery of gods and demigods. Come for her quest of self-discovery, stay for the moments of musical surprise.

-Kyle Orland

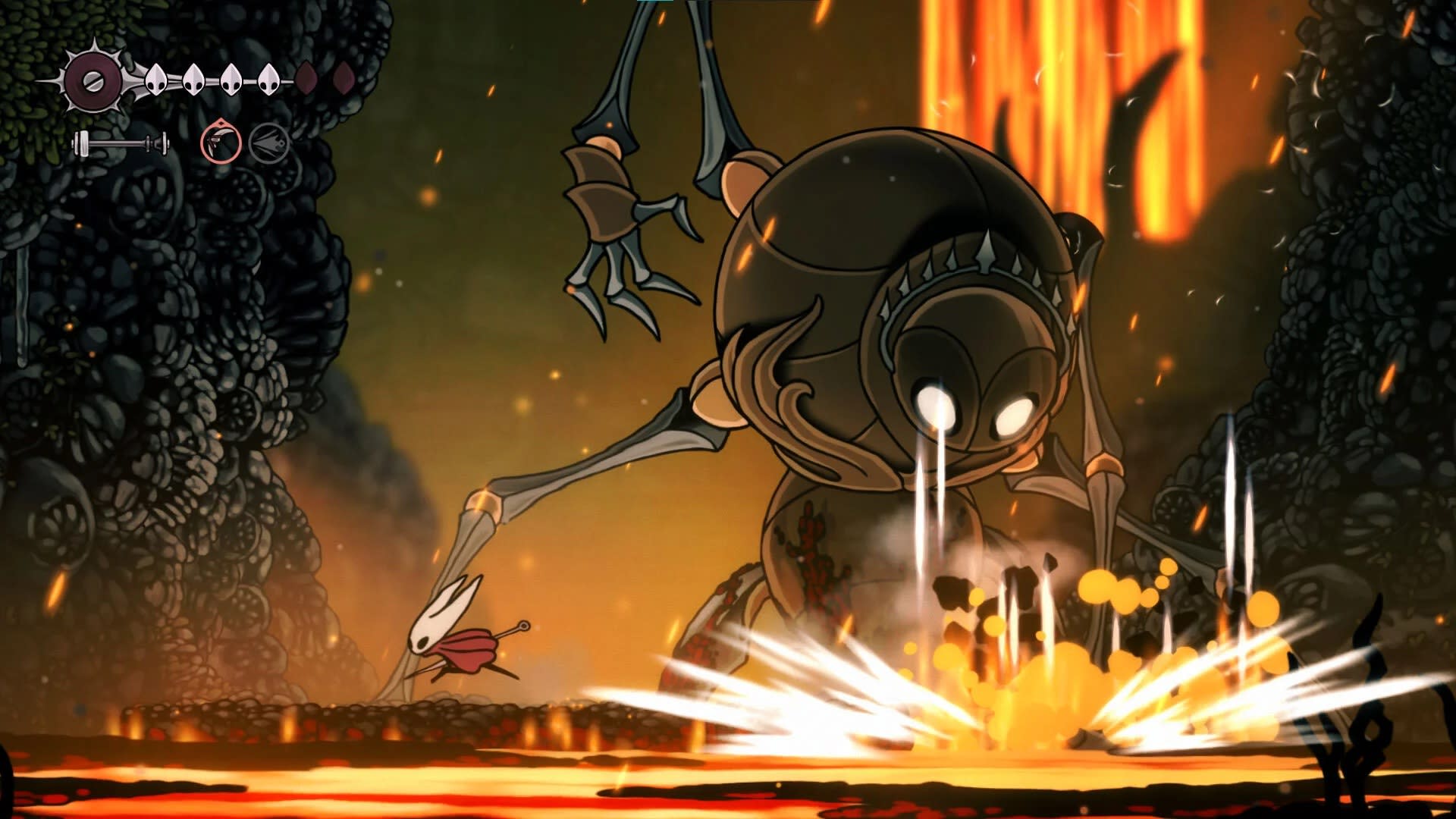

Hollow Knight: Silksong

Team Cherry; Windows, MacOS, Linux, PS4/5, Xbox One/Series X|S, Switch, Switch 2

Piece of cake. Credit: Team Cherry

A quickie sequel in the year or two after Hollow Knight’s out-of-nowhere success in 2017 might have been able to get away with just being a more-of-the-same glorified expansion pack. But after over eight years of overwhelming anticipation from fans, Silksong had to really be something special to live up to its promise.

Luckily, it is. Silksong is a beautiful expansion of the bug-scale underground universe created in the first game. Every new room is a work of painterly beauty, with multiple layers of detailed 2D art drawing you further into its intricate and convincing fallen world.

The sprawling map seems to extend forever in every direction, circling back around and in on itself with plenty of optional alleyways in which to get lost searching for rare power-ups. And while the game is a punishingly hard take on action platforming, there’s usually a way around the most difficult reflex tests for players willing to explore and think a bit outside the box.

Even players who hit a wall and never make it through the sprawling tunnels of Silksong’s labyrinthine underground will still find plenty of memorable moments in whatever portion of the game they do experience.

-Kyle Orland

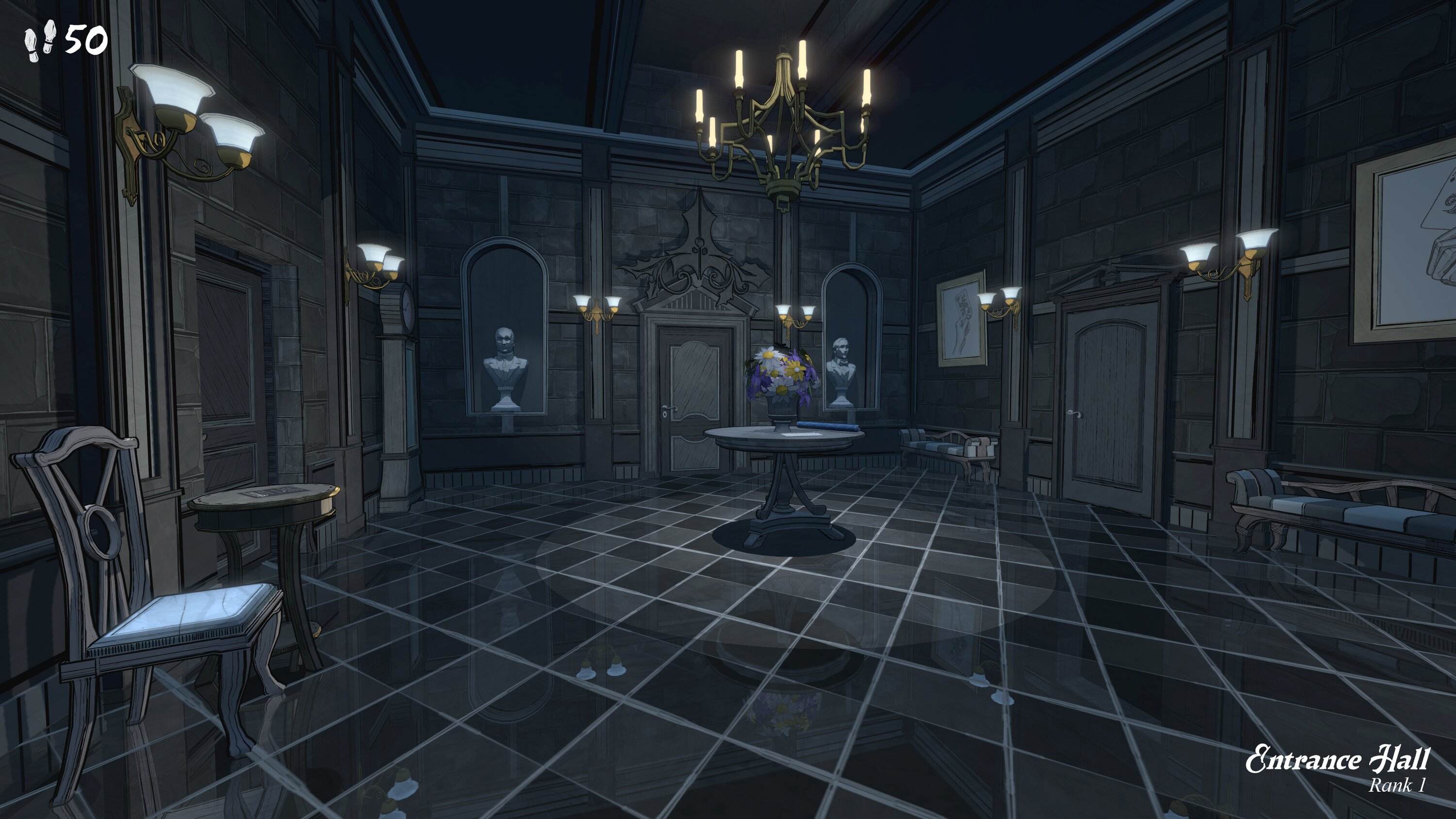

The King Is Watching

Hypnohead; Windows

A lot of good resource tiles there, but the king can only look at six at a time. Credit: Hypnohead / Steam

In a real-time-strategy genre that can often feel too bloated and complex for its own good, The King Is Watching is a streamlined breath of fresh air. Since the entire game takes place on a single screen, there’s no need to constantly pan and zoom your camera around a sprawling map. Instead, you can stay laser-focused on your 5×5 grid of production space and on which portion of it is actively productive under the king’s limited gaze at any particular moment.

Arranging tiles to maximize that production of basic resources and military units quickly becomes an all-consuming juggling act, requiring constant moment-to-moment decisions that can quickly cascade through a run. I’m also a big fan of the game’s self-selecting difficulty system, which asks you to choose how many enemies you think you can take in coming waves, doling out better rewards for players who are willing to push themselves to the limit of their current capabilities.

The bite-size serving of a single King Is Watching run ensures that even failure doesn’t feel too crushing. And success brings with it just enough in the way of semi-permanent ability expansions to encourage another run where you can reach even greater heights of production and protection.

-Kyle Orland

Kingdom Come: Deliverance II

Warhorse Studios; Windows, PS5, Xbox Series X|S

Kingdom Come: Deliverance was a slog that I had to will myself to complete. It was sometimes a broken and janky game, but despite its warts, I saw the potential for something special. And that’s what its sequel, Kingdom Come: Deliverance II, has delivered.

While it’s still a slow burn, the overall experience has been greatly refined, the initial challenge has been smoothed out, and I’ve rarely been more immersed in an RPG’s storytelling. There’s no filler, as every story beat and side quest offers a memorable tale that further paints the setting and characters of medieval Bohemia.

Unlike most RPGs, there’s no magic to be had, which is a big part of the game’s charm. As Henry of Skalitz, you are of meager social standing, and many characters you speak to will be quick to remind you of it. While Henry is a bit better off than his humble beginnings in the first game, you’re no demigod that can win a large battle single-handedly. In fact, you’ll probably lose fairly often in the early goings if more than one person is attacking you.

Almost every fight is a slow dance once you’re in a full suit of armor, and your patience and timing will be the key to winning over the stats of your equipment. But therein lies the beauty of KC:D II: Every battle you pick, whether physical or verbal, carries some weight to your experience and shapes Bohemia for better or worse.

-Jacob May

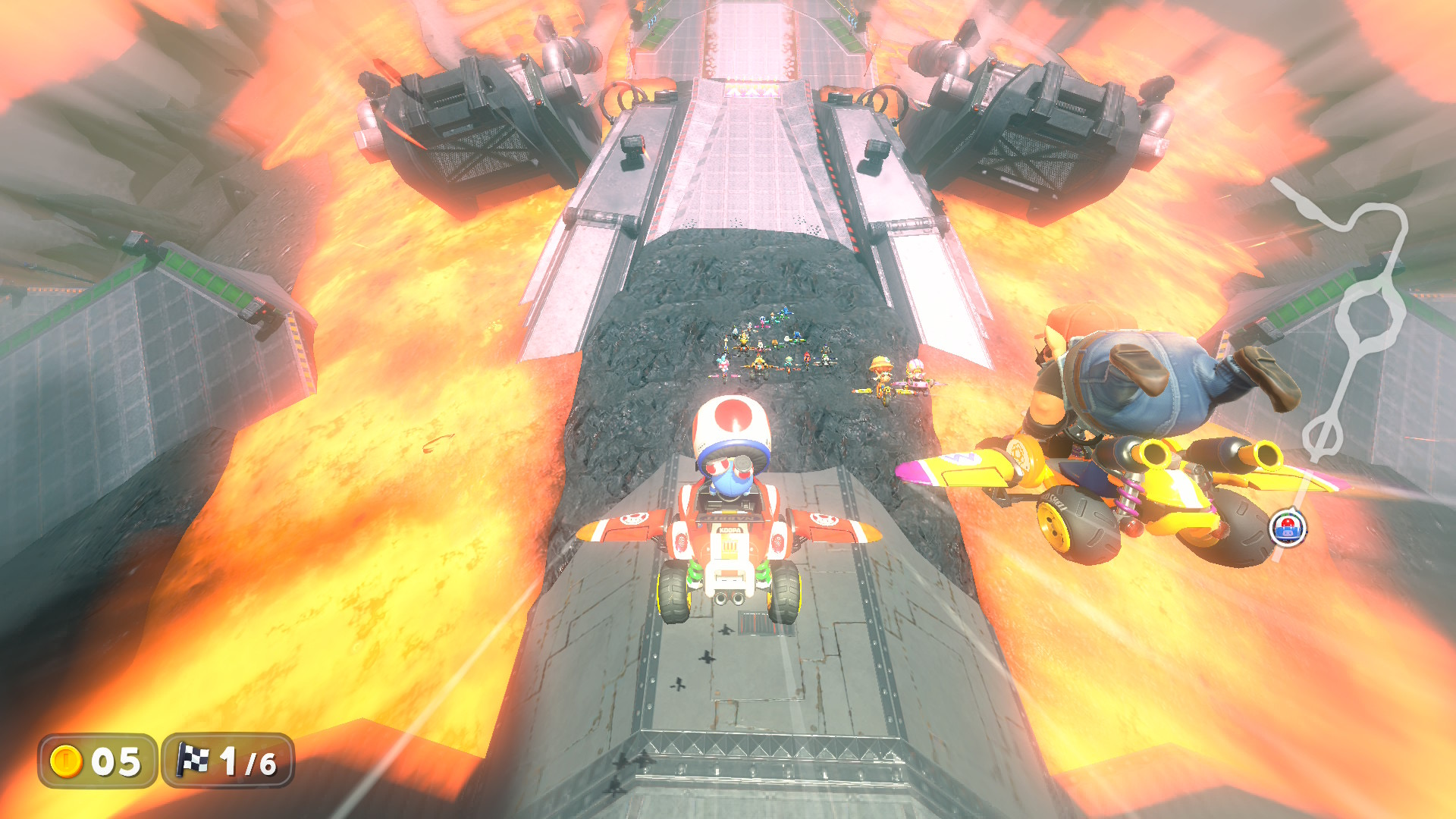

Mario Kart World

Nintendo; Switch 2

Credit: Nintendo

After the incredible success of Mario Kart 8 and its various downloadable content packs on the Switch, Nintendo could have easily done a prettier “more of the same” sequel as the launch-window showcase for the Switch 2. Instead, the company took a huge gamble in trying to transform Mario Kart’s usual distinct tracks into a vast, interconnected open world.

This conceit works best in “Free Roam” mode, where you can explore the outskirts of the standard tracks and the wide open spaces in between for hundreds of mini-challenges that test your driving speed and precision. Add in dozens of collectible medallions and outfits hidden in hard-to-reach corners, and the mode serves as a great excuse to explore every nook and cranny of a surprisingly detailed and fleshed-out world map.

I was also a big fan of Knockout Mode, which slowly whittles a frankly overwhelming field of 24 initial racers to a single winner through a series of endurance rally race checkpoints. These help make up for a series of perplexing changes that hamper the tried-and-true Battle Mode formula and long straightaway sections that feel more than a little bit stifling in the standard Grand Prix mode. Still, Free Roam mode had me happily whiling away dozens of hours with my new Switch 2 this year.

-Kyle Orland

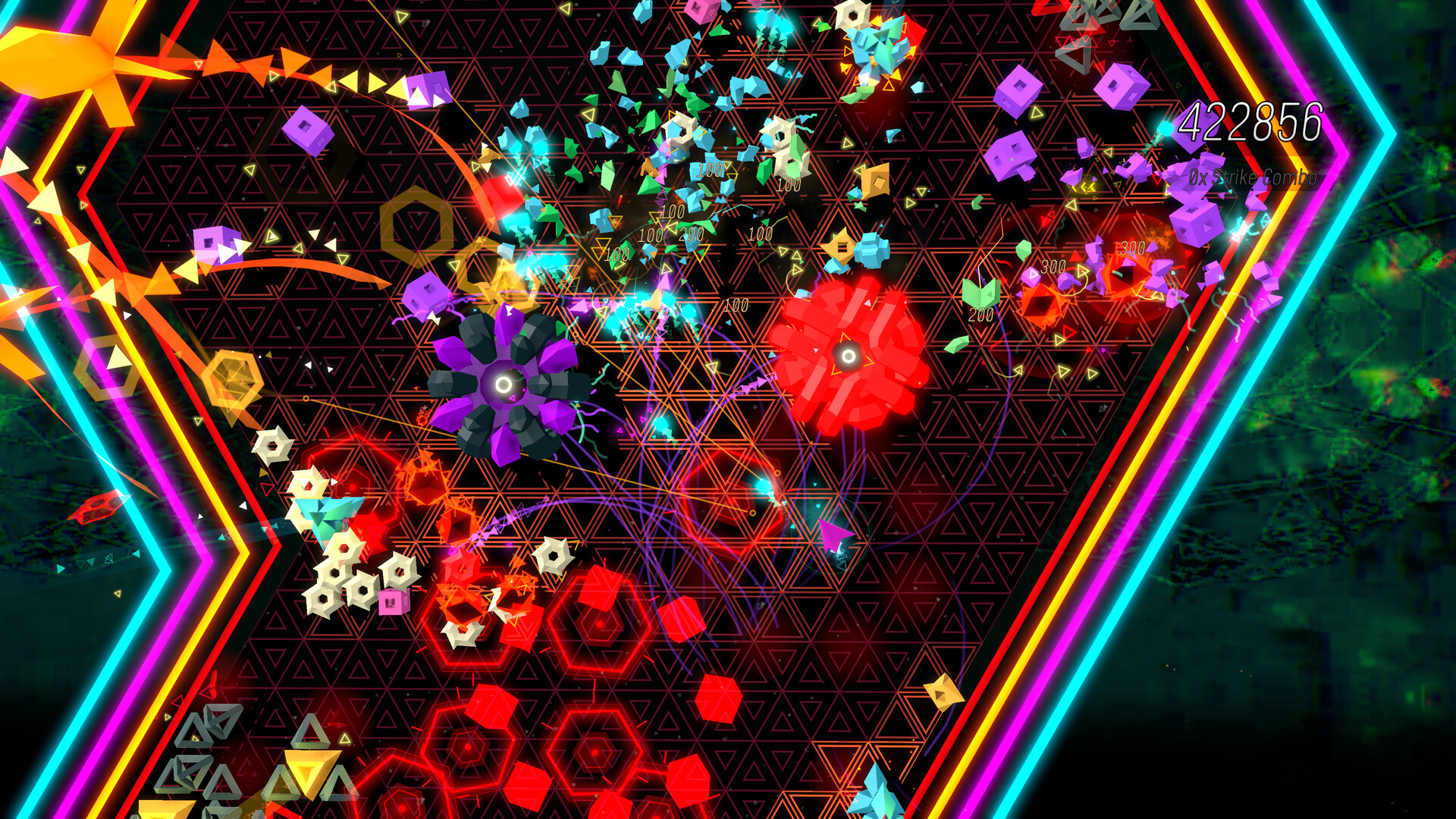

Sektori

Kimmo Lahtinen; Windows, PS5, Xbox Series X|S

For decades now, I’ve been looking for a twin-stick shooter that fully captures the compulsive thrill of the Geometry Wars franchise. Sektori, a late-breaking addition to this year’s top games list, is the first game I can say does so without qualification.

Like Geometry Wars, Sektori has you weaving through a field filled with simple shapes that quickly fill your personal space with ruthless efficiency. But Sektori advances that basic premise with an elegant “strike” system that lets you dash through encroaching enemies and away from danger with the tap of a shoulder button. Advanced players can get a free, instant strike refill by dashing into an upgrade token, and stringing those strikes together creates an excellent risk-vs-reward system of survival versus scoring.

Sektori also features an excellent Gradius-style upgrade system that forces you to decide on the fly whether to take basic power-ups or save up tokens for more powerful weaponry and/or protection further down the line. And just when the basic gameplay threatens to start feeling stale, the game throws in a wide variety of bosses and new modes that mix things up just enough to keep you twitching away.

Throw in an amazing soundtrack and polished presentation that makes even the most crowded screens instantly comprehensible, and you have a game I can see myself coming back to for years—until my reflexes are just too shot to keep up with the frenetic pace anymore.

-Kyle Orland

Kyle Orland has been the Senior Gaming Editor at Ars Technica since 2012, writing primarily about the business, tech, and culture behind video games. He has journalism and computer science degrees from University of Maryland. He once wrote a whole book about Minesweeper.

Ars Technica’s Top 20 video games of 2025 Read More »