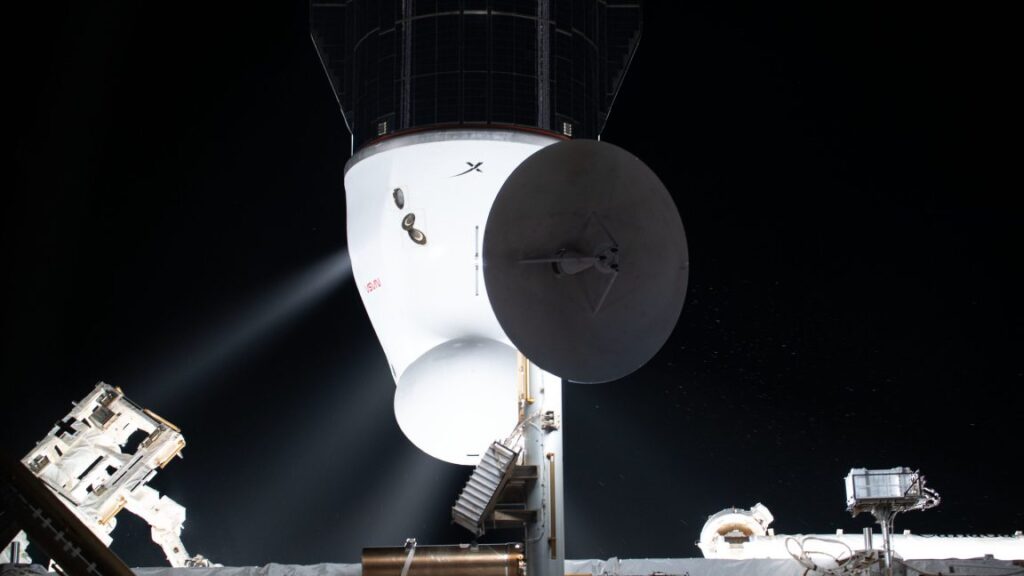

After key Russian launch site is damaged, NASA accelerates Dragon supply missions

With a key Russian launch pad out of service, NASA is accelerating the launch of two Cargo Dragon spaceships in order to ensure that astronauts on board the International Space Station have all the supplies they need next year.

According to the space agency’s internal schedule, the next Dragon supply mission, CRS-34, is moving forward one month from June 2026 to May. And the next Dragon supply mission after this, CRS-35, has been advanced three months from November to August.

A source indicated that the changing schedules are a “direct result” of a launch pad incident on Thanksgiving Day at the Russian spaceport in Baikonur, Kazakhstan.

The issue occurred when a Soyuz rocket launched Roscosmos cosmonauts Sergei Kud-Sverchkov and Sergei Mikayev, as well as NASA astronaut Christopher Williams, on an eight-month mission to the International Space Station. The rocket had no difficulties, but a large mobile platform below the rocket was not properly secured prior to the launch and crashed into the flame trench below, taking the pad offline.

Repairs require at least four months

Russia has other launch pads, both within its borders and neighboring countries, including Kazakhstan, that were formerly part of the Soviet Union. However, Site 31 at Baikonur is the country’s only pad presently configured to handle launches of the Soyuz rocket and two spacecraft critical to the space station, the cargo-only Progress vehicle and the Soyuz crew capsule.

Since the accident Russia’s main space corporation, Roscosmos, has been assessing plans to repair the Site 31 launch site and begun to schedule the delivery of spare parts. Roscosmos officials have told NASA it will take at least four months to repair the site and recover the capability to launch from there.

After key Russian launch site is damaged, NASA accelerates Dragon supply missions Read More »