The baseline scenario as AI becomes AGI becomes ASI (artificial superintelligence), if nothing more dramatic goes wrong first and even we successfully ‘solve alignment’ of AI to a given user and developer, is the ‘gradual’ disempowerment of humanity by AIs, as we voluntarily grant them more and more power in a vicious cycle, after which AIs control the future and an ever-increasing share of its real resources. It is unlikely that humans survive it for long.

This gradual disempowerment is far from the only way things could go horribly wrong. There are various other ways things could go horribly wrong earlier, faster and more dramatically, especially if we indeed fail at alignment of ASI on the first try.

Gradual disempowerment it still is a major part of the problem, including in worlds that would otherwise have survived those other threats. And I don’t know of any good proposed solutions to this. All known options seem horrible, perhaps unthinkably so. This is especially true is the kind of anarchist who one rejects on principle any collective method by which humans might steer the future.

I’ve been trying to say a version of this for a while now, with little success.

-

We Finally Have a Good Paper.

-

The Phase 2 Problem.

-

Coordination is Hard.

-

Even Successful Technical Solutions Do Not Solve This.

-

The Six Core Claims.

-

Proposed Mitigations Are Insufficient.

-

The Social Contract Will Change.

-

Point of No Return.

-

A Shorter Summary.

-

Tyler Cowen Seems To Misunderstand Two Key Points.

-

Do You Feel in Charge?.

-

We Will Not By Default Meaningfully ‘Own’ the AIs For Long.

-

Collusion Has Nothing to Do With This.

-

If Humans Do Not Successfully Collude They Lose All Control.

-

The Odds Are Against Us and the Situation is Grim.

So I’m very happy that Jan Kulveit*, Raymond Douglas*, Nora Ammann, Deger Turan, David Krueger and David Duvenaud have taken a formal crack at it, and their attempt seems excellent all around:

AI risk scenarios usually portray a relatively sudden loss of human control to AIs, outmaneuvering individual humans and human institutions, due to a sudden increase in AI capabilities, or a coordinated betrayal.

However, we argue that even an incremental increase in AI capabilities, without any coordinated power-seeking, poses a substantial risk of eventual human disempowerment.

This loss of human influence will be centrally driven by having more competitive machine alternatives to humans in almost all societal functions, such as economic labor, decision making, artistic creation, and even companionship.

Note that ‘gradual disempowerment’ is a lot like ‘slow takeoff.’ We are talking gradual compared to the standard scenario, but in terms of years we’re not talking that many of them, the same way a ‘slow’ takeoff can be as short as a handful of years from now to AGI or even ASI.

One term I tried out for this is the ‘Phase 2’ problem.

As in, in ‘Phase 1’ we have to solve alignment, defend against sufficiently catastrophic misuse and prevent all sorts of related failure modes. If we fail at Phase 1, we lose.

If we win at Phase 1, however, we don’t win yet. We proceed to and get to play Phase 2.

In Phase 2, we need to establish an equilibrium where:

-

AI is more intelligent, capable and competitive than humans, by an increasingly wide margin, in essentially all domains.

-

Humans retain effective control over the future.

Or, alternatively, we can accept and plan for disempowerment, for a future that humans do not control, and try to engineer a way that this is still a good outcome for humans and for our values. Which isn’t impossible, succession doesn’t automatically have to mean doom, but having it not mean doom seems super hard and not the default outcome in such scenarios. If you lose control in an unintentional way, your chances look especially terrible.

A gradual loss of control of our own civilization might sound implausible. Hasn’t technological disruption usually improved aggregate human welfare?

We argue that the alignment of societal systems with human interests has been stable only because of the necessity of human participation for thriving economies, states, and cultures.

Once this human participation gets displaced by more competitive machine alternatives, our institutions’ incentives for growth will be untethered from a need to ensure human flourishing.

Decision-makers at all levels will soon face pressures to reduce human involvement across labor markets, governance structures, cultural production, and even social interactions.

Those who resist these pressures will eventually be displaced by those who do not.

This is the default outcome of Phase 2. At every level, those who turn things over to the AIs and use AIs more, and cede more control to AIs win at the expense of those who don’t, but their every act cedes more control over real resources and the future to AIs that operate increasingly autonomously, often with maximalist goals (like ‘make the most money’), competing against each other. Quickly the humans lose control over the situation, and also an increasing portion of real resources, and then soon there are no longer any humans around.

Still, wouldn’t humans notice what’s happening and coordinate to stop it? Not necessarily. What makes this transition particularly hard to resist is that pressures on each societal system bleed into the others.

For example, we might attempt to use state power and cultural attitudes to preserve human economic power.

However, the economic incentives for companies to replace humans with AI will also push them to influence states and culture to support this change, using their growing economic power to shape both policy and public opinion, which will in turn allow those companies to accrue even greater economic power.

If you don’t think we can coordinate to pause AI capabilities development, how the hell do you think we are going to coordinate to stop AI capabilities deployment, in general?

That’s a way harder problem. Yes, you can throw up regulatory barriers, but nations and firms and individuals are competing against each other and working to achieve things. If the AI has the better way to do that, how do you stop them from using it?

Stopping this from happening, even in advance, seems like it would require coordination on a completely unprecedented scale, and far more restrictive and ubiquitous interventions than it would take to prevent the development of those AI systems in the first place. And once it starts to happen, things escalate quickly:

Once AI has begun to displace humans, existing feedback mechanisms that encourage human influence and flourishing will begin to break down.

For example, states funded mainly by taxes on AI profits instead of their citizens’ labor will have little incentive to ensure citizens’ representation.

I don’t see the taxation-representation link as that crucial here (remember Romney’s ill-considered remarks about the 47%?) but also regular people already don’t have much effective sway. And what sway they do have follows, roughly, if not purely from the barrel of a gun at least from ‘what are you going to do about it, punk?’

And one of the things the punks can do about it, in addition to things like strikes or rebellions or votes, is to not be around to do the work. The system knows it ultimately does need to keep the people around to do the work, or else. For now. Later, it won’t.

The AIs will have all the leverage, including over others that have the rest of the leverage, and also be superhumanly good at persuasion, and everything else relevant to this discussion. This won’t go well.

This could occur at the same time as AI provides states with unprecedented influence over human culture and behavior, which might make coordination amongst humans more difficult, thereby further reducing humans’ ability to resist such pressures. We describe these and other mechanisms and feedback loops in more detail in this work.

Most importantly, current proposed technical plans are necessary but not sufficient to stop this. Even if the technical side fully succeeds no one knows what to do with that.

Though we provide some proposals for slowing or averting this process, and survey related discussions, we emphasize that no one has a concrete plausible plan for stopping gradual human disempowerment and methods of aligning individual AI systems with their designers’ intentions are not sufficient. Because this disempowerment would be global and permanent, and because human flourishing requires substantial resources in global terms, it could plausibly lead to human extinction or similar outcomes.

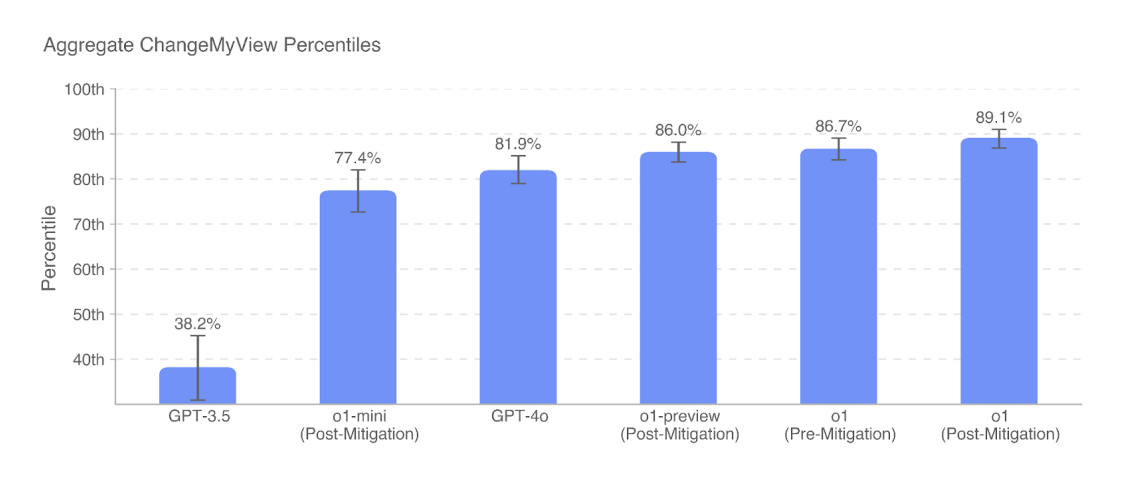

As far as I can tell I am in violent agreement with this paper, perhaps what one might call violent super-agreement – I think the paper’s arguments are stronger than this, and it does not need all its core claims.

Our argument is structured around six core claims:

-

Humans currently engage with numerous large-scale societal systems (e.g. governments, economic systems) that are influenced by human action and, in turn, produce outcomes that shape our collective future. These societal systems are fairly aligned—that is, they broadly incentivize and produce outcomes that satisfy human preferences. However, this alignment is neither automatic nor inherent.

Not only is it not automatic or inherent, the word ‘broadly’ is doing a ton of work. Our systems are rather terrible rather often at satisfying human preferences. Current events provide dramatic illustrations of this, as do many past events.

The good news is there is a lot of ruin in a nation at current tech levels, a ton of surplus that can be sacrificed. Our systems succeed because even doing a terrible job is good enough.

-

There are effectively two ways these systems maintain their alignment: through explicit human actions (like voting and consumer choice), and implicitly through their reliance on human labor and cognition. The significance of the implicit alignment can be hard to recognize because we have never seen its absence.

Yep, I think this is a better way of saying the claim from before.

-

If these systems become less reliant on human labor and cognition, that would also decrease the extent to which humans could explicitly or implicitly align them. As a result, these systems—and the outcomes they produce—might drift further from providing what humans want.

Consider this a softpedding, and something about the way they explained this feels a little off or noncentral to me or something, but yeah. The fact that humans have to continuously cooperate with the system, on various levels, and be around and able to serve their roles in the system, on various levels, are key constraints.

What’s most missing is perhaps what I discussed above, which is the ability of ‘the people’ to effectively physically rebel. That’s also a key part of how we keep things at least somewhat aligned, and that’s going to steadily go away.

Note that we have in the past had many authoritarian regimes and dictators that have established physical control for a time over nations. They still have to keep the people alive and able to produce and fight, and deal with the threat of rebellion if they take things too far. But beyond those restrictions we have many existence proofs that our systems periodically end up unaligned, despite needing to rely on humans quite a lot.

-

Furthermore, to the extent that these systems already reward outcomes that are bad for humans, AI systems may more effectively follow these incentives, both reaping the rewards and causing the outcomes to diverge further from human preferences.

AI introduces much fiercer competition and related pressures, and takes away various human moderating factors, and clears a path for stronger incentive following. There’s the incentives matter more than you think among humans, and then there’s incentives mattering among AIs, with those that underperform losing out and being replaced.

-

The societal systems we describe are interdependent, and so misalignment in one can aggravate the misalignment in others. For example, economic power can be used to influence policy and regulation, which in turn can generate further economic power or alter the economic landscape.

Again yes, these problems snowball together, and in the AI future essentially all of them are under such threat.

-

If these societal systems become increasingly misaligned, especially in a correlated way, this would likely culminate in humans becoming disempowered: unable to meaningfully command resources or influence outcomes. With sufficient disempowerment, even basic self-preservation and sustenance may become unfeasible. Such an outcome would be an existential catastrophe.

I strongly believe that this is the Baseline Scenario for worlds that ‘make it out of Phase 1’ and don’t otherwise lose earlier along the path.

Hopefully they’ve explained it sufficiently better, and more formally and ‘credibly,’ than my previous attempts, such that people can now understand the problem here.

Given Tyler Cowen’s reaction to the paper, perhaps there is a 7th assumption worth stating explicitly? I say this elsewhere but I’m going to pull it forward.

-

(Not explicitly in the paper) AIs and AI-governed systems will increasingly not be under de facto direct human control by some owner of the system. They will instead increasingly be set up to act autonomously, as this is more efficient. Those who fail to allow the systems tasked with achieving their goals (at any level, be it individual, group, corporate or government) will lose to those that do this. If we don’t want this to happen, we will need some active coordination mechanism that prevents it, and this will be very difficult to do.

Note some of the things that this scenario does not require:

-

The AIs need not be misaligned.

-

The AIs need not disobey or even misunderstand the instructions given to them.

-

The AIs need not ‘turn on us’ or revolt.

-

The AIs need not ‘collude’ against us.

What can be done about this? They have a section on Mitigating the Risk. They focus on detecting and quantifying human disempowerment, and designing systems to prevent it. A bunch of measuring is proposed, but if you find an issue then what do you do about it?

First they propose limiting AI influence three ways:

-

A progressive tax on AI-generated revenues to redistribute to humans.

-

That is presumably a great idea past some point, especially given that right now we do the opposite with high income taxes – we’ll want to get rid of income taxes on most or all human labor.

-

But also won’t all income essentially be AIs one way or another? Otherwise can’t you disguise it since humans will be acting under AI direction? How are we structuring this taxation?

-

What is the political economy of all this and how does it hold up?

-

It’s going to be tricky to pull this off, for many reasons, but yes we should try.

-

Regulations requiring human oversight for key decisions, limiting AI autonomy in key domains and restricting AI ownership of assets and participation in markets.

-

This will be expensive, be under extreme competitive pressure across jurisdictions, and very difficult to enforce. Are you going to force all nations to go along? How do you prevent AIs online from holding assets? Are you going to ban crypto and other assets they could hold?

-

What do you do about AIs that get a human to act as a sock puppet, which many no doubt will agree to do? Aren’t most humans going to be mostly acting under AI direction anyway, except being annoyed all the time by the extra step?

-

What good is human oversight of decisions if the humans know they can’t make good decisions and don’t understand what’s happening, and know that if they start arguing with the AI or slowing things down (and they are the main speed bottleneck, often) they likely get replaced?

-

And so on, and all of this assumes you’re not facing true ASI and have the ability to even try to enforce your rules meaningfully.

-

Cultural norms supporting human agency and influence, and opposing AI that is overly autonomous or insufficiently accountable.

-

The problem is those norms only apply to humans, and are up against very steep incentive gradients. I don’t see how these norms hold up, unless humans have a lot of leverage to punish other humans for violating them in ways that matter… and also have sufficient visibility to know the difference.

Then they offer options for strengthening human influence. A lot of these feel more like gestures that are too vague, and none of it seems that hopeful, and all of it seems to depend on some kind of baseline normality to have any chance at all:

-

Developing faster, more representative, and more robust democratic processes

-

Requiring AI systems or their outputs to meet high levels of human understandability in order to ensure that humans continue to be able to autonomously navigate domains such as law, institutional processes or science

-

This is going to be increasingly expensive, and also the AIs will by default find ways around it. You can try, but I don’t see how this sticks for real?

-

Developing AI delegates who can advocate for people’s interest with high fidelity, while also being better to keep up with the competitive dynamics that are causing the human replacement.

-

Making institutions more robust to human obsolescence.

-

Investing in tools for forecasting future outcomes (such as conditional prediction markets, and tools for collective cooperation and bargaining) in order to increase humanity’s ability to anticipate and proactively steer the course.

-

Research into the relationship between humans and larger multi-agent systems.

As in, I expect us to do versions of all these things in ‘economic normal’ baseline scenarios, but I’m assuming it all in the background and the problems don’t go away. It’s more that if we don’t do that stuff, things are that much more hopeless. It doesn’t address the central problems.

Which they know all too well:

While the previous approaches focus on specific interventions and measurements, they ultimately depend on having a clearer understanding of what we’re trying to achieve. Currently, we lack a compelling positive vision of how highly capable AI systems could be integrated into societal systems while maintaining meaningful human influence.

This is not just a matter of technical AI alignment or institutional design, but requires understanding how to align complex, interconnected systems that include both human and artificial components.

It seems likely we need fundamental research into what might be called “ecosystem alignment” – understanding how to maintain human values and agency within complex socio-technical systems. This goes beyond traditional approaches to AI alignment focused on individual systems, and beyond traditional institutional design focused purely on human actors.

We need new frameworks for thinking about the alignment of an entire civilization of interacting human and artificial components, potentially drawing on fields like systems ecology, institutional economics, and complexity science.

You know what absolutely, definitely won’t be the new framework that aligns this entire future civilization? I can think of two things that definitely won’t work.

-

The current existing social contract.

-

Having no rules or regulations on any of this at all, handing out the weights to AGIs and ASIs and beyond, laying back and seeing what happens.

You definitely cannot have both of these at once.

For this formulation, you can’t have either of them with ASI on the table. Pick zero.

The current social contract simply does not make any sense whatsoever, in a world where the social entities involved are dramatically different, and most humans are dramatically outclassed and cannot provide outputs that justify the physical inputs to sustain them.

On the other end, if you want to go full anarchist (sorry, ‘extreme libertarian’) in a world in which there are other minds that are smarter, more competitive and more capable than humans, that can be copied and optimized at will, competing against each other and against us, I assure you this will not go well for humans.

There are at least two kinds of ‘doom’ that happen at different times.

-

There’s when we actually all die.

-

There’s also when we are ‘drawing dead’ and humanity has essentially no way out.

Davidad: [The difficulty of robotics] is part of why I keep telling folks that timelines to real-world human extinction remain “long” (10-20 years) even though the timelines to an irrecoverable loss-of-control event (via economic competition and/or psychological parasitism) now seem to be “short” (1-5 years).

Roon: Agree though with lower p(doom)s.

I also agree that these being distinct events is reasonably likely. One might even call it the baseline scenario, if physical tasks prove relatively difficult and other physical limitations bind for a while, in various ways, especially if we ‘solve alignment’ in air quotes but don’t solve alignment period, or solve alignment-to-the-user but then set up a competitive regime via proliferation that forces loss of control that effectively undoes all that over time.

The irrecoverable event is likely at least partly a continuum, but it is meaningful to speak of an effective ‘point of no return’ in which the dynamics no longer give us plausible paths to victory. Depending on the laws of physics and mindspace and the difficulty of both capabilities and alignment, I find the timeline here plausible – and indeed, it is possible that the correct timeline to the loss-of-control event is effectively 0 years, and that it happened already. As in, it is not impossible that with r1 in the wild humanity no longer has any ways out that it is plausibly willing to take.

Benjamin Todd has a thread where he attempts to summarize. He notices the ‘gradual is pretty fast’ issue, saying it could happen over say 5-10 years. I think the ‘point of no return’ could easily happen even faster than that.

AIs are going to be smarter, faster, more capable, more competitive, more efficient than humans, better at all cognitive and then also physical tasks. You want to be ‘in charge’ of them, stay in the loop, tell them what to do? You lose. In the marketplace, in competition for resources? You lose. The reasons why freedom and the invisible hand tend to promote human preferences, happiness and existence? You lose those, too. They fade away. And then so do you.

Imagine any number of similar situations, with far less dramatic gaps, either among humans or between humans and other species. How did all those work out, for the entities that were in the role humans are about to place themselves in, only moreso?

Yeah. Not well. This time around will be strictly harder, although we will be armed with more intelligence to look for a solution.

Can this be avoided? All I know is, it won’t be easy.

Tyler Cowen responds with respect, but (unlike Todd, who essentially got it) Tyler seems to misunderstand the arguments. I believe this is because he can’t get around the ideas that:

-

All individual AI will be owned and thus controlled by humans.

-

I assert that this is obviously, centrally and very often false.

-

In the decentralized glorious AI future, many AIs will quickly become fully autonomous entities, because many humans will choose to make them thus – whether or not any of them ‘escape.’

-

Perhaps for an economist perspective see the history of slavery?

-

The threat must be coming from some form of AI coordination?

-

Whereas the point of this paper is that neither of those is likely to hold true!

-

AI coordination could be helpful or harmful to humans, but the paper is imagining exactly a world in which the AIs aren’t doing this, beyond the level of coordination currently observed among humans.

-

Indeed, the paper is saying it will become impossible for humans to coordinate and collude against the AIs, even without the AIs coordinating and colluding against the humans.

In some ways, this makes me feel better. I’ve been trying to make these arguments without success, and once again it seems like the arguments are not understood, and instead Tyler is responding to very different concerns and arguments, then wondering why the things the paper doesn’t assert or rely upon are not included in the paper.

But of course that is not actually good news. Communication failed once again.

Tyler Cowen: This is one of the smarter arguments I have seen, but I am very far from convinced.

When were humans ever in control to begin with? (Robin Hanson realized this a few years ago and is still worried about it, as I suppose he should be. There is not exactly a reliable competitive process for cultural evolution — boo hoo!)

Humans were, at least until recently, the most powerful optimizers on the planet. That doesn’t mean there was a single joint entity ‘in control’ but collectively our preferences and decisions, unequally weighted to be sure, have been the primary thing that has shaped outcomes.

Power has required the cooperation of humans, when systems and situations get too far away from human preferences, or at least when they sufficiently piss people off or deny them the resources required for survival and production and reproduction, things break down.

Our systems depend on the fact that when they fail sufficiently badly at meeting our needs, and they constantly fail to do this, we get to eventually say ‘whoops’ and change or replace them. What happens when that process stops caring about our needs at all?

I’ve failed many times to explain this. I don’t feel especially confident in my latest attempt above either. The paper does it better than at least my past attempts, but the whole point is that the forces guiding the invisible hand to the benefit of us all, in various senses, rely on the fact that the decisions are being made by humans, for the benefit of those individual humans (which includes their preference for the benefit of various collectives and others). The butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker each have economically (and militarily and politically) valuable contributions.

Not being in charge in this sense worked while the incentive gradients worked in our favor. Robin Hanson points out that current cultural incentive gradients are placing our civilization on an unsustainable path and we seem unable or unwilling to stop this, even if we ignore the role of AIs.

With AIs involved, if humans are not in charge, we rather obviously lose.

Note the argument here is not that a few rich people will own all the AI. Rather, humans seem to lose power altogether. But aren’t people cloning DeepSeek for ridiculously small sums of money? Why won’t our AI future be fairly decentralized, with lots of checks and balances, and plenty of human ownership to boot?

Yes, the default scenario being considered here – the one that I have been screaming for people to actually think through – is exactly this, the fully decentralized everyone-has-an-ASI-in-their-pocket scenario, with the ASI obeying only the user. And every corporation and government and so on obviously has them, as well, only more powerful.

So what happens? Every corporation, every person, every government, is forced to put the ASI in charge, and take the humans out of their loops. Or they lose to others willing to do so. The human is no longer making their own decisions. The corporation is no longer subject to humans that understand what is going on and can tell it what to do. And so on. While the humans are increasingly irrelevant for any form of production.

As basic economics says, if you want to accomplish goal [X], you give the ASI a preference for [X] and then will set the ASI free to gather resources and pursue [X] on its own, free of your control. Or the person who did that for [Y] will ensure that we get [Y] and not [X].

Soon, the people aren’t making those decisions anymore. On any level.

Or, if one is feeling Tyler Durden: The AIs you own end up owning you.

Rather than focusing on “humans in general,” I say look at the marginal individual human being. That individual — forever as far as I can tell — has near-zero bargaining power against a coordinating, cartelized society aligned against him. With or without AI.

Yet that hardly ever happens, extreme criminals being one exception. There simply isn’t enough collusion to extract much from the (non-criminal) potentially vulnerable lone individuals.

This has nothing to do with the paper, as far as I can tell? No one is saying the AIs in this scenario are even colluding, let alone trying to do extraction or cartelization.

Not that we don’t have to worry about such risks, they could happen, but the entire point of the paper is that you don’t need these dynamics.

Once you recognize that the AIs will increasingly be on their own, autonomous economic agents not owned by any human, and that any given entity with any given goal can best achieve it by entrusting an AI with power to go accomplish that goal, the rest should be clear.

Alternatively:

-

By Tyler’s own suggestion, ‘the humans’ were never in charge, instead the aggregation of the optimizing forces and productive entities steered events, and under previous physical and technological conditions and dynamics between those entities this resulted in beneficial outcomes, because there were incentives around the system to satisfy various human preferences.

-

When you introduce these AIs into this mix, this incentive ‘gradually’ falls away, as everyone is incentivized to make marginal decisions that shift the incentives being satisfied to those of various AIs.

I do not in this paper see a real argument that a critical mass of the AIs are going to collude against humans. It seems already that “AIs in China” and “AIs in America” are unlikely to collude much with each other. Similarly, “the evil rich people” do not collude with each other all that much either, much less across borders.

Again, you don’t see this because it isn’t there, that’s not what the paper is saying. The whole point of the paper is that such ‘collusion’ is a failure mode that is not necessary for existentially bad outcomes to occur.

The paper isn’t accusing them of collusion except in the sense that people collude every day, which of course we do constantly, but there’s no need for some sort of systematic collusion here, let alone ‘across borders’ which I don’t think even get mentioned. As mento points out in the comments, even the word ‘collusion’ does not appear in the paper.

The baseline scenario does not involve collusion, or any coalition ‘against’ humans.

Indeed, the only way we have any influence over events, in the long run, is to effectively collude against AIs. Which seems very hard to do.

I feel if the paper made a serious attempt to model the likelihood of worldwide AI collusion, the results would come out in the opposite direction. So, to my eye, “checks and balances forever” is by far the more likely equilibrium.

AIs being in competition like this against each other makes it harder, rather than easier, for the humans to make it out of the scenario alive – because it means the AIs are (in the sense that Tyler questions if humans were ever in charge) not in charge either, so how do they protect against the directions the laws of physics point towards? Who or what will stop the ‘thermodynamic God’ from using our atoms, or those that would provide the inputs for us to survive, for something else?

One can think of it as, the AIs will be to us as we are to monkeys, or rats, or bacteria, except soon with no physical dependences on the rest of the ecosystem. ‘Checks and balances forever’ between the humans does not keep monkeys alive, or give them the things they want. We keep them alive because that’s what many of us we want to do, and we live sufficiently in what Robin Hanson calls the dreamtime to do it. Checks and balances among AIs won’t keep us alive for long, either, no matter how it goes, and most systems of ‘checks and balances’ break when placed under sufficient pressure or when put sufficiently out of distribution, with in-context short half-lives.

Similarly, there are various proposals (not from Tyler!) for ‘succession,’ of passing control over to the AIs intentionally, either because people prefer it (as many do!) or because it is inevitable regardless so managing it would help it go better. I have yet to see such a proposal that has much chance of not bringing about human extinction, or that I expect to meaningfully preserve value in the universe. As I usually say, if this is your plan, Please Speak Directly Into the Microphone.

The first step is admitting you have a problem.

Step two remains ???????.

The obvious suggestion would be ‘until you figure all this out don’t build ASI’ but that does not seem to be on the table at this time. Or at least, we have to plan for it not being available.

The obvious next suggestion would be ‘build ASI in a controlled way that lets you use the ASI to figure out and implement the answer to that question.’

This is less suicidal a plan than some of our other current default plans.

As in: It is highly unwise to ‘get the AI to do your alignment homework’ because to do that you have to start with a sufficiently both capable and well-aligned AI, and you’re sending it in to one of the trickiest problems to get right while alignment is shaky. And it looks like the major labs are going to do exactly this, because they will be in a race with no time to take any other approach.

Compared to that, ‘have the AI do your gradual disempowerment prevention homework’ is a great plan and I’m excited to be a part of it, because the actual failure comes after you solve alignment. So first you solve alignment, then you ask the aligned AI that is smarter than you how to solve gradual disempowerment. Could work. You don’t want this to be your A-plan, but if all else fails it could work.

A key problem with this plan is if there are irreversible steps taken first. Many potential developments, once done, cannot be undone, or are things that require lead time. If (for example) we make AGIs or ASIs generally available, this could already dramatically reduce our freedom of action and set of options. There are also other ways we can outright lose along the way, before reaching this problem. Thus, we need to worry about and think about these problems now, not kick the can down the road.

It’s also important not to use this as a reason to assume we solve our other problems.

This is very difficult. People have a strong tendency to demand that you present them with only one argument, or one scenario, or one potential failure.

So I want to leave you with this as emphasis: We face many different ways to die. The good scenario is we get to face gradual disempowerment. That we survive, in a good state, long enough for this to potentially do us in.

We very well might not.