Google adds photo-to-video generation with Veo 3 to the Gemini app

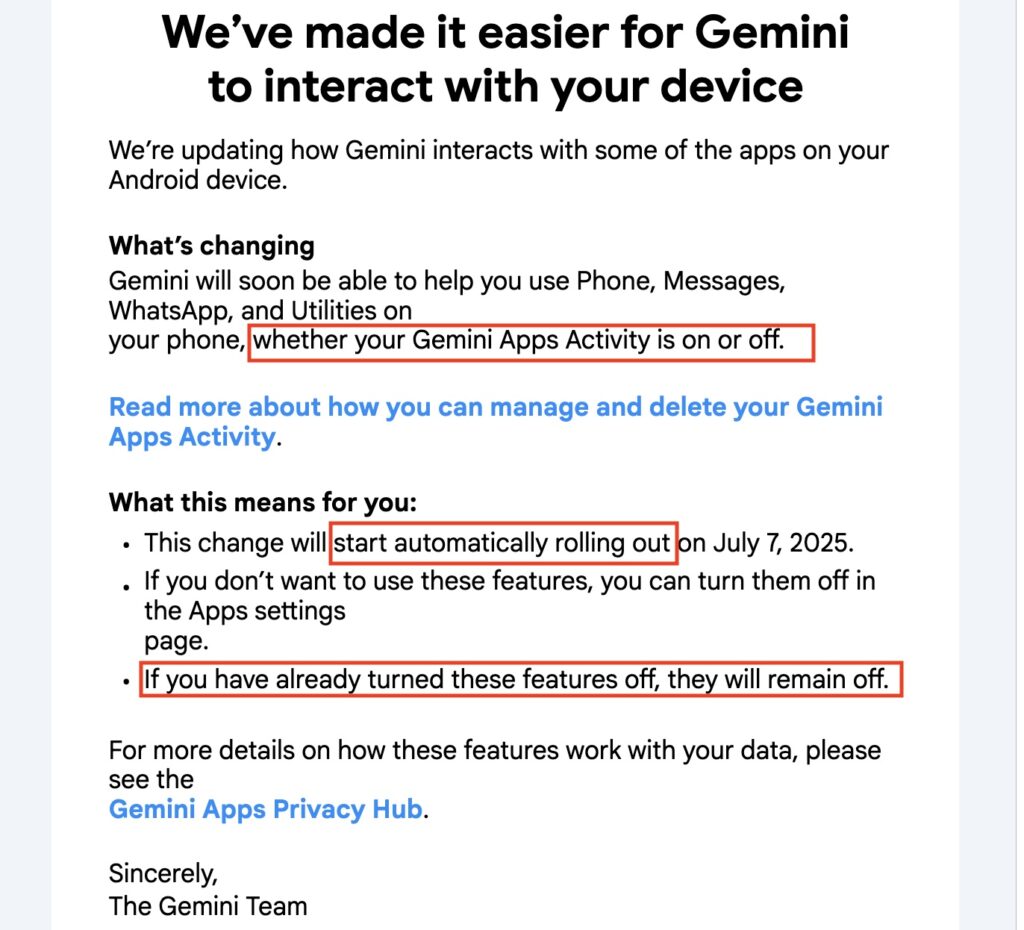

Google’s Veo 3 videos have propagated across the Internet since the model’s debut in May, blurring the line between truth and fiction. Now, it’s getting even easier to create these AI videos. The Gemini app is gaining photo-to-video generation, allowing you to upload a photo and turn it into a video. You don’t have to pay anything extra for these Veo 3 videos, but the feature is only available to subscribers of Google’s Pro and Ultra AI plans.

When Veo 3 launched, it could conjure up a video based only on your description, complete with speech, music, and background audio. This has made Google’s new AI videos staggeringly realistic—it’s actually getting hard to identify AI videos at a glance. Using a reference photo makes it easier to get the look you want without tediously describing every aspect. This was an option in Google’s Flow AI tool for filmmakers, but now it’s in the Gemini app and web interface.

To create a video from a photo, you have to select “Video” from the Gemini toolbar. Once this feature is available, you can then add your image and prompt, including audio and dialogue. Generating the video takes several minutes—this process takes a lot of computation, which is why video output is still quite limited.

Google adds photo-to-video generation with Veo 3 to the Gemini app Read More »