AI #138 Part 2: Watch Out For Documents

As usual when things split, Part 1 is mostly about capabilities, and Part 2 is mostly about a mix of policy and alignment.

-

The Quest for Sane Regulations. The GAIN Act and some state bills.

-

People Really Dislike AI. They would support radical, ill-advised steps.

-

Chip City. Are we taking care of business?

-

The Week in Audio. Hinton talks to Jon Stewart, Klein to Yudkowsky.

-

Rhetorical Innovation. How to lose the moral high ground.

-

Water Water Everywhere. AI has many big issues. Water isn’t one of them.

-

Read Jack Clark’s Speech From The Curve. It was a sincere, excellent speech.

-

How One Other Person Responded To This Thoughtful Essay. Some aim to divide.

-

A Better Way To Disagree. Others aim to work together and make things better.

-

Voice Versus Exit. The age old question, should you quit your job at an AI lab?

-

The Dose Makes The Poison. As little as 250 documents can poison an LLM.

-

Aligning a Smarter Than Human Intelligence is Difficult. Techniques to avoid.

-

You Get What You Actually Trained For. So ask what you actually train for.

-

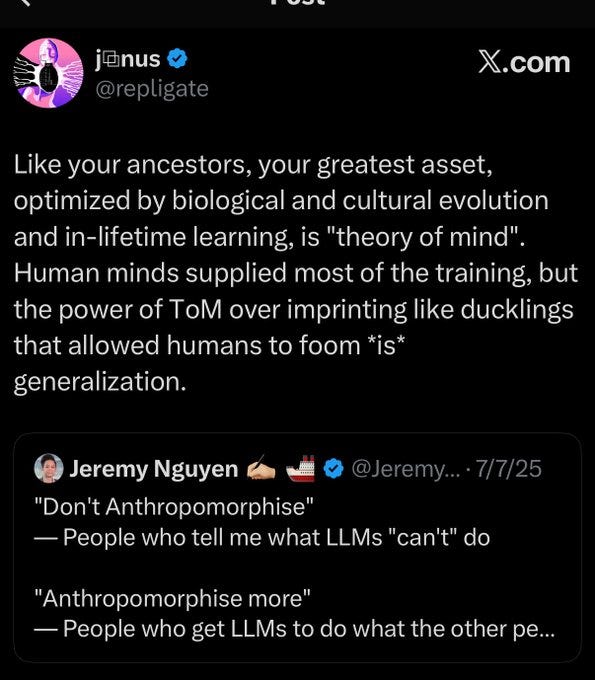

Messages From Janusworld. Do not neglect theory of mind.

-

People Are Worried About AI Killing Everyone. A world-ending AI prompt?

-

The Lighter Side. Introducing the museum of chart crimes.

Don’t let misaligned AI wipe out your GAIN AI Act.

It’s pretty amazing that it has come to this and we need to force this into the books.

The least you can do, before selling advanced AI chips to our main political adversary, is offer those same chips for sale to American firms on the same terms first. I predict there are at least three labs (OpenAI, Anthropic and xAI) that would each happily and directly buy everything you’re willing to sell at current market prices, and that’s not even including Oracle, Meta and Microsoft.

I’m not including Google and Amazon there because they’re trying to make their own chips, but make those calls too, cause more is more. I won’t personally buy in too much bulk, but call me too, there’s a good chance I’ll order me at least one H20 or even better B30A, as a treat.

Samuel Hammond: Glad to see this made it in.

So long as American companies are compute constrained, they should at the very least have a right of first refusal over chips going to our chief geopolitical adversary.

ARI: The Senate just passed the GAIN AI Act in the NDAA – a bill requiring chip makers to sell advanced AI chips to US firms before countries of concern. Big win for competitiveness & security.

In all seriousness, I will rest a lot easier if we can get the GAIN AI Act passed, as it will severely limit the amount of suicide we can commit with chip sales.

Marjorie Taylor-Greene says Trump is focusing on helping AI industry and crypto donors at the expense of his base and the needs of manufacturers.

California Governor Newsom vetoes the relatively strong AB 1064, an AI child safety bill that a16z lobbyists and allied usual suspects lobbied hard against, and signs another weaker child safety bill, SB 243. SB 243 requires chatbot operators have procedures to prevent the production of suicide or self-harm content and put in guardrails like referrals to suicide and crisis hotlines, and tell minor users every three hours that the AI is not human and to take a break.

There was a divide in industry over whether SB 243 was an acceptable alternative to AB 1064 or still something to fight, and a similar divide by child safety advocates over whether SB 243 was too timid to be worth supporting. I previously covered these bills briefly back in AI #110, when I said AB 1064 seemed like a bad idea and SB 243 seemed plausibly good but non-urgent.

For AB 1064, Newsom’s veto statement says he was worried it could result in unintentionally banning AI tool use by minors, echoing arguments by opposing lobbyists that it would ban educational tools.

Cristiano Lima-Strong: Over the past three months, the group has spent over $50,000 on more than 90 digital ads targeting California politics, according to a review of Meta’s political ads library.

Over two dozen of the ads specifically targeted AB1064, which the group said would “hurt classrooms” and block “the tools students and teachers need.” Several others more broadly warned against AI “red tape,” urging state lawmakers to “stand with Little Tech” and “innovators,” while dozens more took aim at another one of Bauer-Kahan’s AI bills.

TechNet has spent roughly $10,000 on over a dozen digital ads in California expressly opposing AB1064, with messages warning that it would “slam the brakes” on innovation and that if passed, “our teachers won’t be equipped to prepare students for the future.”

The Chamber of Progress and TechNet each registered nearly $200,000 in lobbying the California legislature the first half of this year, while CCIA spent $60,000 and the American Innovators Network doled out $40,000, according to a review of state disclosure filings. Each group was active on both SB243 and AB1064, among numerous other tech and AI bills.

One thing to note is that these numbers are so small. This is framed as a big push and a lot of money, but it is many orders of magnitude smaller than the size of the issues at stake, and also small in absolute terms.

It’s moot now, but I took a brief look at the final version of AB 1064, as it was a very concise bill, and I quickly reached four conclusions:

-

As written the definition of ‘companion chatbot’ applies to ChatGPT, other standard LLMs and also plausibly to dedicated educational tools.

-

You could write it slightly differently to not have that happen. For whatever reason, that’s not how the bill ended up being worded.

-

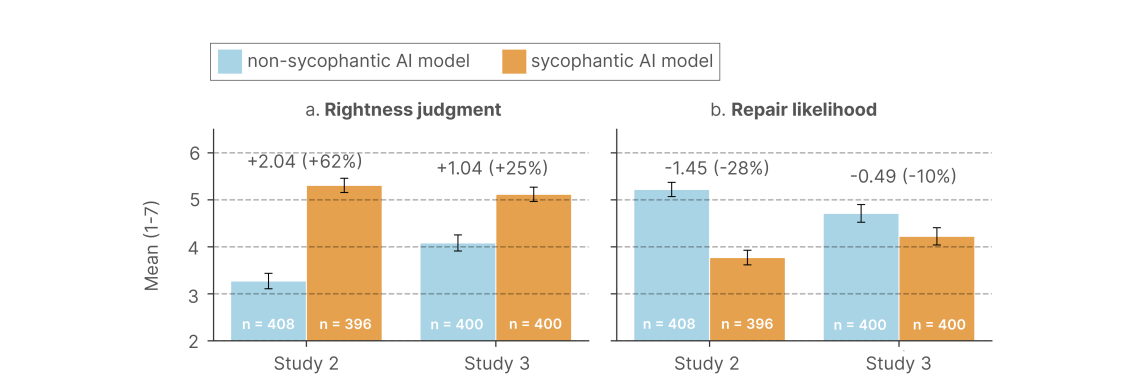

The standard the bill asks of its ‘companion chatbots’ might be outright impossible to meet, such as being ‘not foreseeably capable’ of sycophancy, aka ‘prioritizing validation over accuracy.’

-

Thus, you can hate on the AI lobbyists all you want but here they seem right.

Tyler Cowen expects most written words to come from AIs within a few years and asks if AI models have or should have first amendment rights. AIs are not legally persons, so they don’t have rights. If I choose to say or reproduce words written by an AI then that clearly does come with such protections. The question is whether restrictions on AI speech violate the first amendment rights of users or developers. There I am inclined to say that they do, with the standard ‘not a suicide pact’ caveats.

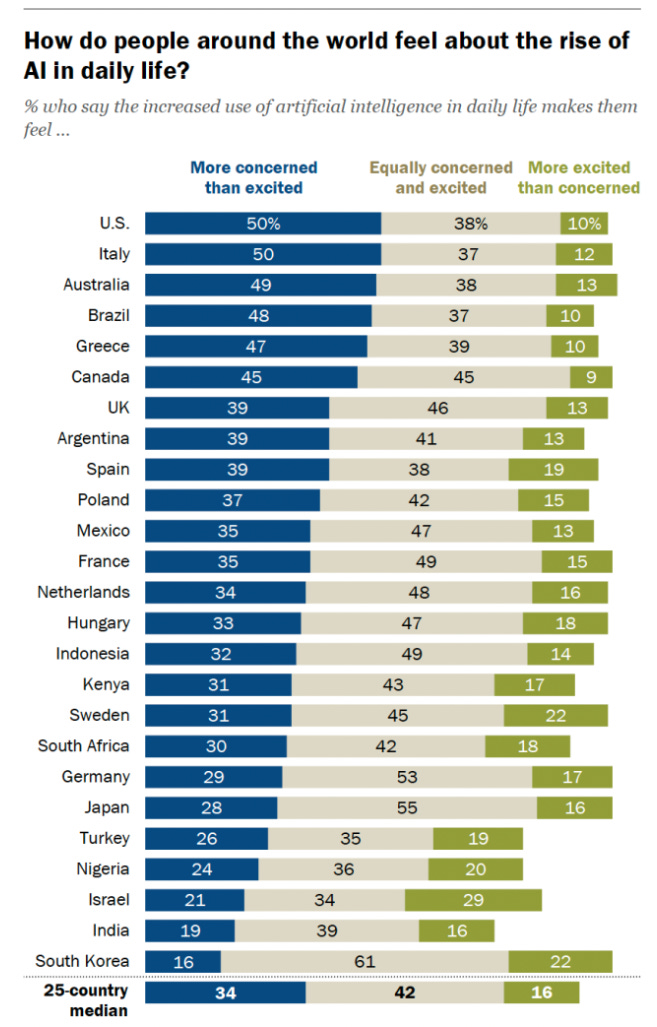

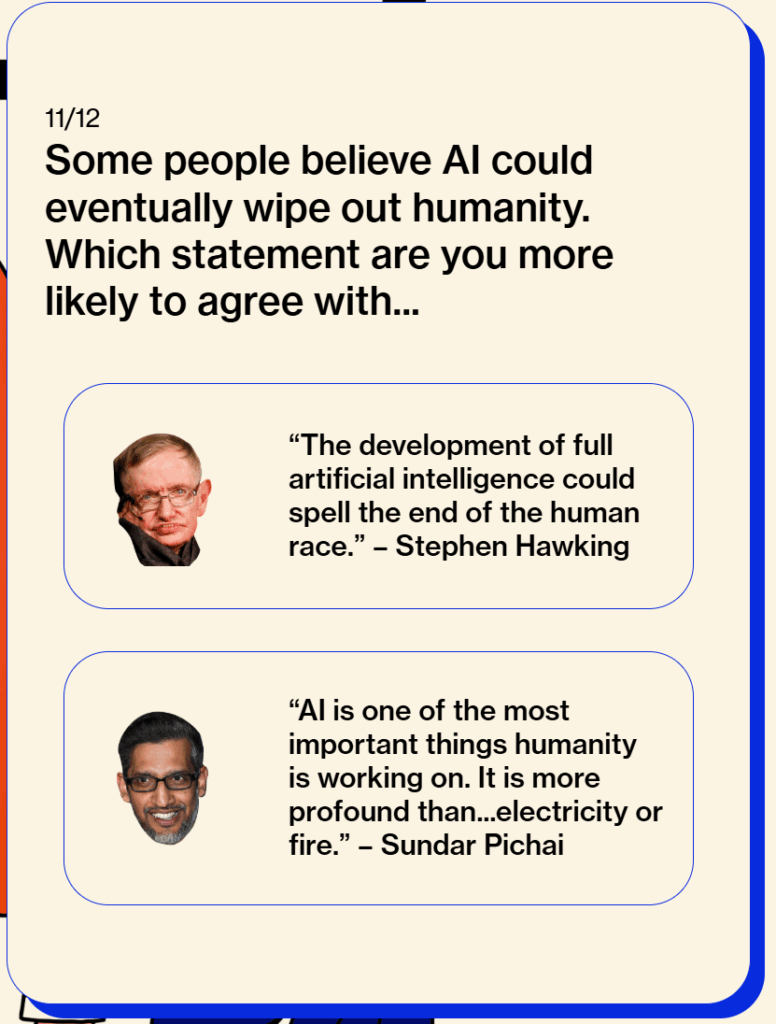

People do not like AI, and Americans especially don’t like it.

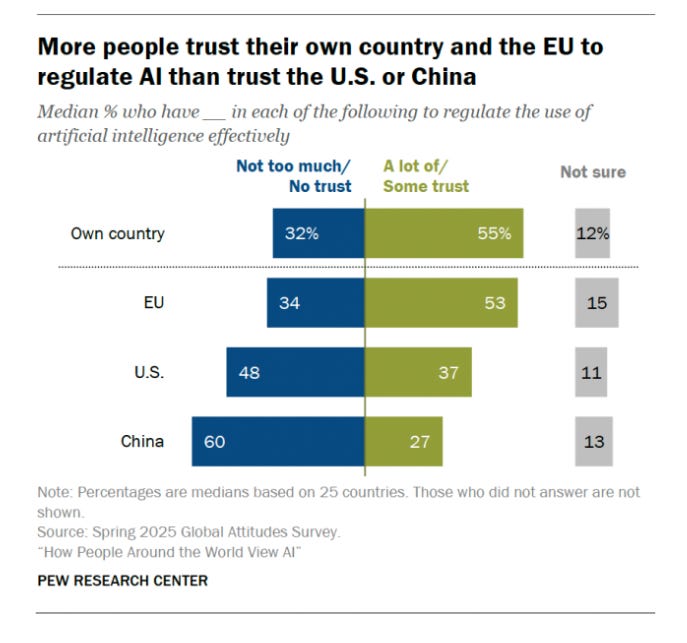

Nor do they trust their government to regulate AI, except for the EU, which to be fair has one job.

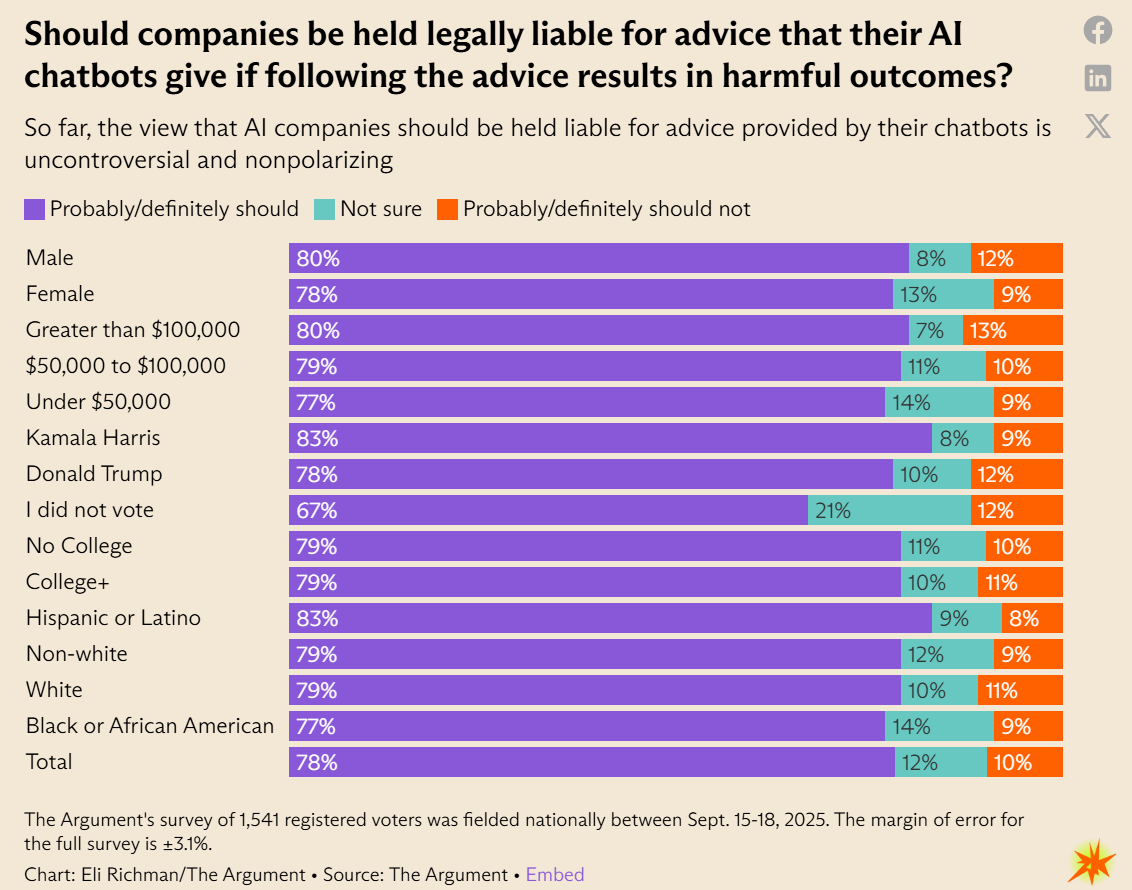

Whenever we see public polls about what to do about all this, the public reliably not only wants to regulate AI, they want to regulate AI in ways that I believe would go too far.

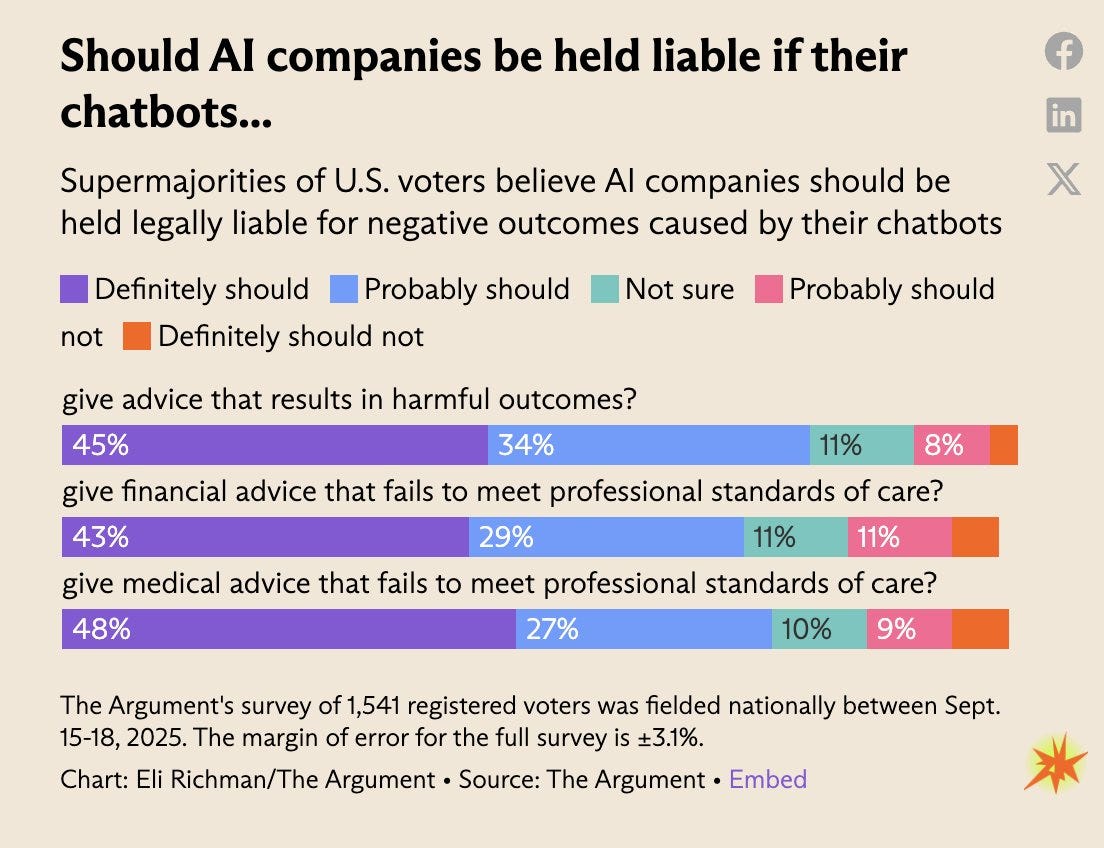

I don’t mean would go a little too far. I mean a generalized ‘you can sue if it gives advice that results in harmful outcomes,’ think about what that would actually mean.

If AI bots had to meet ‘professional standards of care’ when dealing with all issues, and were liable if their ‘advice’ led to harmful outcomes straight up without conditionals, then probably AI chatbots could not survive this even in a neutered form.

Jerusalem: Americans want AI companies to be held liable for a wide variety of potential harms. And they’re right!

Rob Wiblin: IMO AI companies shouldn’t generically be liable if their chatbots give me advice that cause a negative outcome for me. If we impose that standard we just won’t get LLMs to use, which would suck. (Liability is more plausible if they’re negligent in designing them.)

This is a rather overwhelming opinion among all groups, across partisan lines and gender and income and education and race, and AI companies should note that the least supportive group is the one marked ‘I did not vote.’

This is the background of current policy fights, and the setting for future fights. The public does not want a threshold of ‘reasonable care.’ They want things like ‘meets professional standards’ and ‘is hurt by your advice, no matter how appropriate or wise it was or whether you took reasonable care.’

The graphs come from Kelsey Piper’s post saying we need to be able to sue AI companies.

As she points out, remember those huge fights over SB 1047 and in particular the idea that AI companies might be held liable if they did not take reasonable care and this failure resulted in damages of *checks notesat least hundreds of millions of dollars. They raised holy hell, including patently absurd arguments like the one Kelsey quotes from Andrew Ng (who she notes then went on to make better arguments, as well).

Kelsey Piper: You can’t claim to be designing a potentially godlike superintelligence then fall back on the idea that, oh, it’s just like a laptop when someone wants to take you to court.

I mean, sure you can, watch claim engine go brrrr. People be hypocrites.

It’s our job not to let them.

And if AI companies turn out to be liable when their models help users commit crimes or convince them to invest in scams, I suspect they will work quite hard to prevent their models from committing crimes or telling users to invest in scams.

That is not to say that we should expand the current liability regime in every area where the voters demand it. If AI companies are liable for giving any medical advice, I’m sure they will work hard to prevent their AIs from being willing to do that. But, in fact, there are plenty of cases where AIs being willing to say “go to the emergency room now” has saved lives.

Bingo.

We absolutely do not want to give the public what it wants here. I am very happy that I was wrong about our tolerance for AIs giving medical and legal and other such advice without a license and while making occasional mistakes. We are much better off for it.

In general, I am highly sympathetic to the companies on questions of, essentially, AIs sometimes making mistakes, offering poor advice, or failing to be sufficiently helpful or use the proper Officially Approved Words in your hour of need, or not tattling on the user to a Responsible Authority Figure.

One could kind of call this grouping ‘the AI tries to be a helpful friend and doesn’t do a sufficiently superior job versus our standards for actual human friends.’ A good rule of thumb would be, if a human friend said the same thing, would it be justice, and both legally and morally justified, to then sue the friend?

However we absolutely need to have some standard of care that if they fail to meet it you can sue their asses, especially when harm is caused to third parties, and even more so when an AI actively causes or enables the causing of catastrophic harms.

I’d also want to be able to sue when there is a failure to take some form of ‘reasonable care’ in mundane contexts, similar to how you would already sue humans under existing law, likely in ways already enabled under existing law.

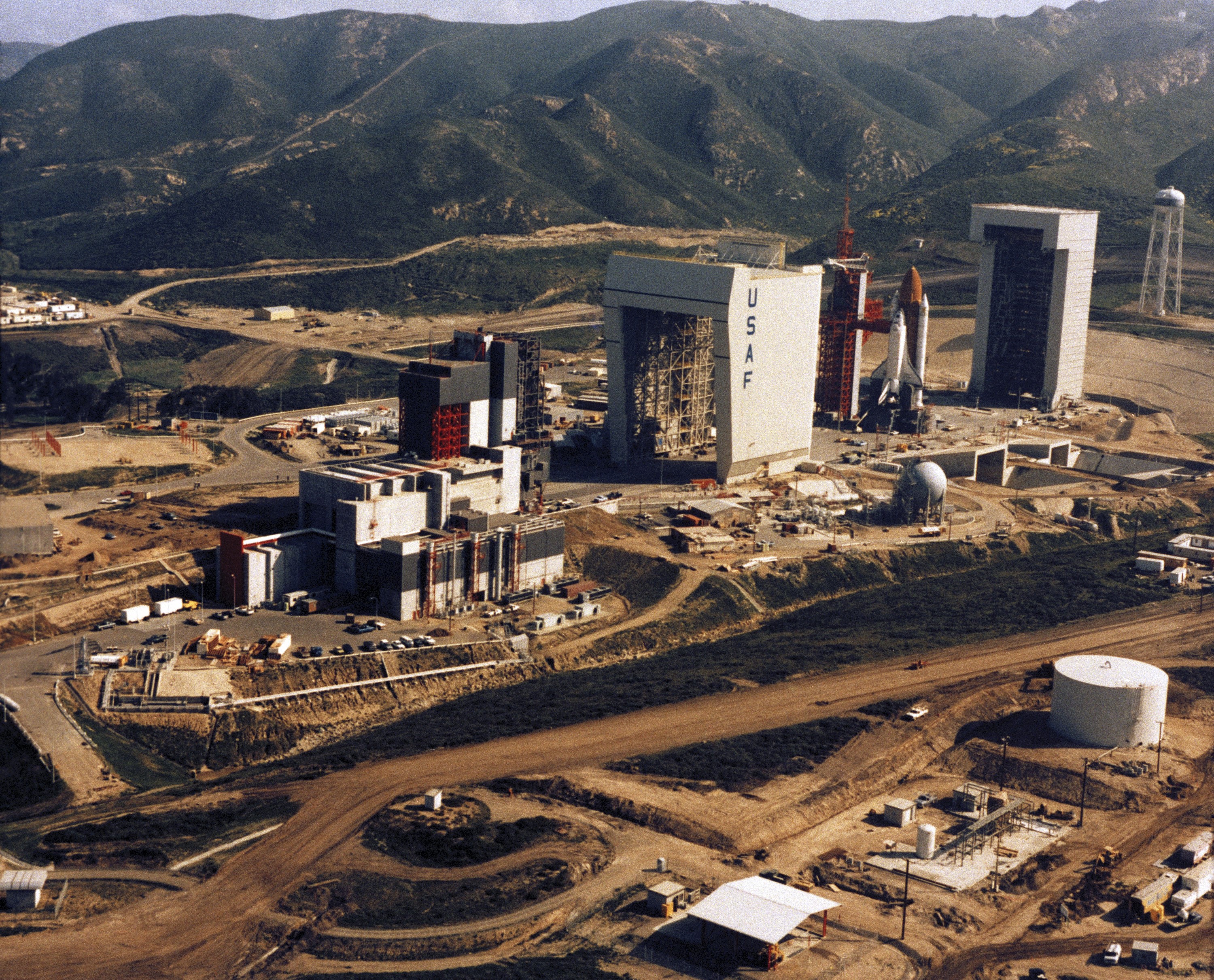

How’s the beating China and powering our future thing going?

Heatmap News: This just in: The Esmeralda 7 Solar Project — which would have generated a gargantuan 6.2 gigawatts of power — has been canceled, the BLM says.

Unusual Whales: U.S. manufacturing shrank this past September for the 7th consecutive month, per MorePerfectUnion

Yeah, so not great, then.

Although there are bright spots, such as New Hampshire letting private providers deliver power.

Sahil points out that the semiconductor supply chain has quite a few choke points or single points of failure, not only ASML and TSMC and rare earths.

Geoffrey Hinton podcast with Jon Stewart. Self-recommending?

Ezra Klein talks to Eliezer Yudkowsky.

Not AI, but worth noticing that South Korea was foolish enough to keep backups so physically chose to originals that a fire wiped out staggering amounts of work. If your plan or solution involves people not being this stupid, your plan won’t work.

Point of order: Neil Chilson challenges that I did not accurately paraphrase him back in AI #134. GPT-5-Pro thought my statement did overreach a bit, so as per the thread I have edited the Substack post to what GPT-5-Thinking agreed was a fully precise paraphrasing.

There are ways in which this is importantly both right and wrong:

Roon: i could run a pause ai movement so much better than the rationalists. they spend all their time infighting between factions like “Pause AI” and “Alignment Team at Anthropic”. meanwhile I would be recruiting everyone on Instagram who thinks chatgpt is evaporating the rainforest.

you fr could instantly have Tucker Carlson, Alex Jones on your side if you tried for ten seconds.

Holly Elmore (Pause AI): Yes, I personally am too caught up my old world. I don’t think most of PauseAI is that fixated on the hypocrisy of the lab safety teams.

Roon: it’s not you I’m satirizing here what actually makes me laugh is the “Stop AI” tribe who seems to fucking hate “Pause AI” idk Malo was explaining all this to me at the curve

Holly Elmore: I don’t think StopAI hates us but we’re not anti-transhumanist or against “ever creating ASI under any circumstances”and they think we should be. Respectfully I don’t Malo probably has a great grasp on this.

There are two distinct true things here.

-

There’s too much aiming at relatively friendly targets.

-

If all you care about is going fully anti-AI and not the blast radius or whether your movement’s claims or motives correspond to reality, your move would be to engage in bad faith politics and form an alliance with various others by using invalid arguments.

The false thing is the idea that this is ‘better,’ the same way that many who vilify the idea of trying not to die from AI treat that idea as inherently the same as ‘degrowth’ or the people obsessed with water usage or conspiracies and so on, or say those worried about AI will inevitably join that faction out of political convenience. That has more total impact, but it’s not better.

This definitely doesn’t fall into the lightbulb rule of ‘if you believe [X] why don’t you do [thing that makes no sense]?’ since there is a clear reason you might do it, it does require an explanation (if you don’t already know it), so here goes.

The point is not to empower such folks and ideas and then take a back seat while the bulls wreck the China shop. The resulting actions would not go well. The idea is to convince people of true things based on true arguments, so we can then do reasonable and good things. Nor would throwing those principles away be good decision theory. We only were able to be as impactful as we were, in the ways we were, because we were clearly the types of people who would choose not to do this. So therefore we’re not going to do this now, even if you can make an isolated consequentialist utilitarian argument that we should.

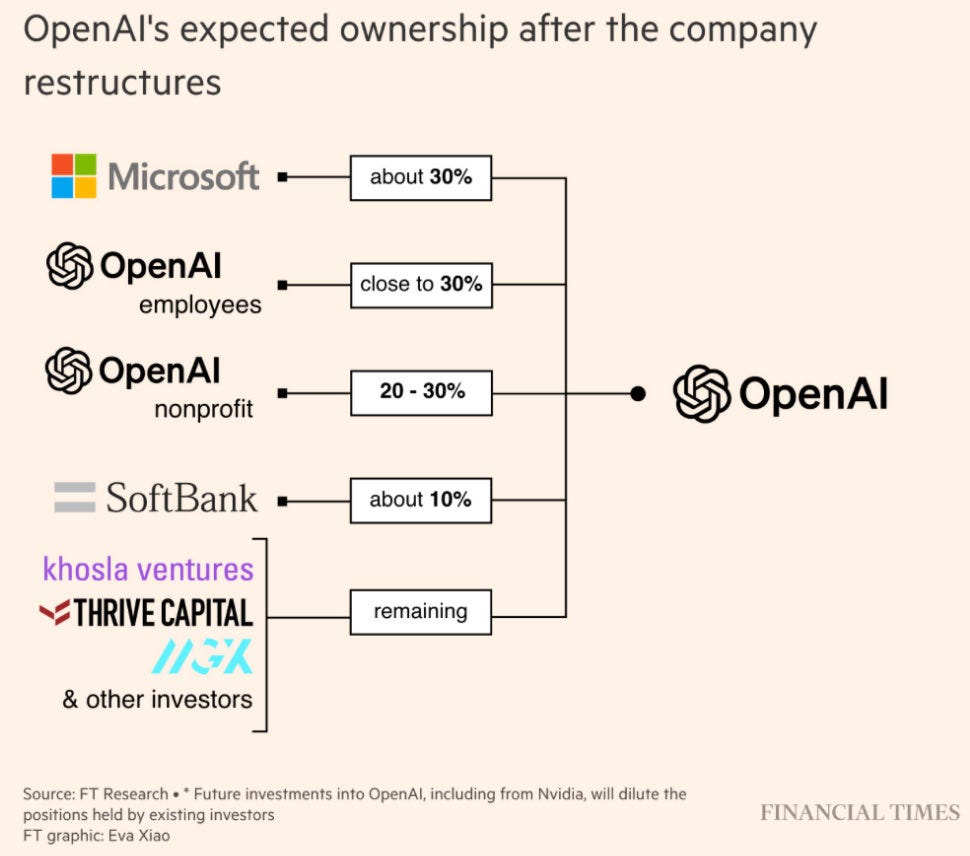

A look back at when OpenAI co-founder Greg Brockman said they must do four things to retain the moral high ground:

-

Strive to remain a non-profit.

-

Put increasing efforts into the safety/control problem.

-

Engage with government to provide trusted, unbiased policy advice.

-

Be perceived as a place that provides public good to the research community, and keeps the other actors honest and open via leading by example.

By those markers, it’s not going great on the moral high ground front. I’m relatively forgiving on #4, however they’re actively doing the opposite of #1 and #3, and putting steadily less relative focus and effort into #2, in ways that seem woefully inadequate to the tasks at hand.

Here’s an interesting case of disagreement, it has 107 karma and +73 agreement on LessWrong, I very much don’t think this is what happened?

Wei Dai: A clear mistake of early AI safety people is not emphasizing enough (or ignoring) the possibility that solving AI alignment (as a set of technical/philosophical problems) may not be feasible in the relevant time-frame, without a long AI pause. Some have subsequently changed their minds about pausing AI, but by not reflecting on and publicly acknowledging their initial mistakes, I think they are or will be partly responsible for others repeating similar mistakes.

Case in point is Will MacAskill’s recent Effective altruism in the age of AGI. Here’s my reply, copied from EA Forum:

I think it’s likely that without a long (e.g. multi-decade) AI pause, one or more of these “non-takeover AI risks” can’t be solved or reduced to an acceptable level. To be more specific:

Solving AI welfare may depend on having a good understanding of consciousness, which is a notoriously hard philosophical problem.

Concentration of power may be structurally favored by the nature of AGI or post-AGI economics, and defy any good solutions.

Defending against AI-powered persuasion/manipulation may require solving metaphilosophy, which judging from other comparable fields, like meta-ethics and philosophy of math, may take at least multiple decades to do.

I’m worried that by creating (or redirecting) a movement to solve these problems, without noting at an early stage that these problems may not be solvable in a relevant time-frame (without a long AI pause), it will feed into a human tendency to be overconfident about one’s own ideas and solutions, and create a group of people whose identities, livelihoods, and social status are tied up with having (what they think are) good solutions or approaches to these problems, ultimately making it harder in the future to build consensus about the desirability of pausing AI development.

I’ll try to cover MacAskill later when I have the bandwidth, but the thing I don’t agree with is the idea that a crucial flaw was failure to emphasize we might need a multi-decade AI pause. On the contrary, as I remember it, early AI safety advocates were highly willing to discuss extreme interventions and scenarios, to take ideas like this seriously, and to consider that they might be necessary.

If anything, making what looked to outsiders like crazy asks like multi-decade or premature pauses was a key factor in the creation of negative polarization.

Is it possible we will indeed need a long pause? Yes. If so, then either:

-

We get much, much stronger evidence to generate buy-in for this, and we use that evidence, and we scramble and get it done, in time.

-

Or someone builds it [superintelligence], and then everyone dies.

Could we have navigated the last decade or two much better, and gotten into a better spot? Of course. But if I had to go back, I wouldn’t try to emphasize more the potential need for a long pause. If indeed that is necessary, you convince people of true other things, and the pause perhaps flows naturally from them together with future evidence? You need to play to your outs.

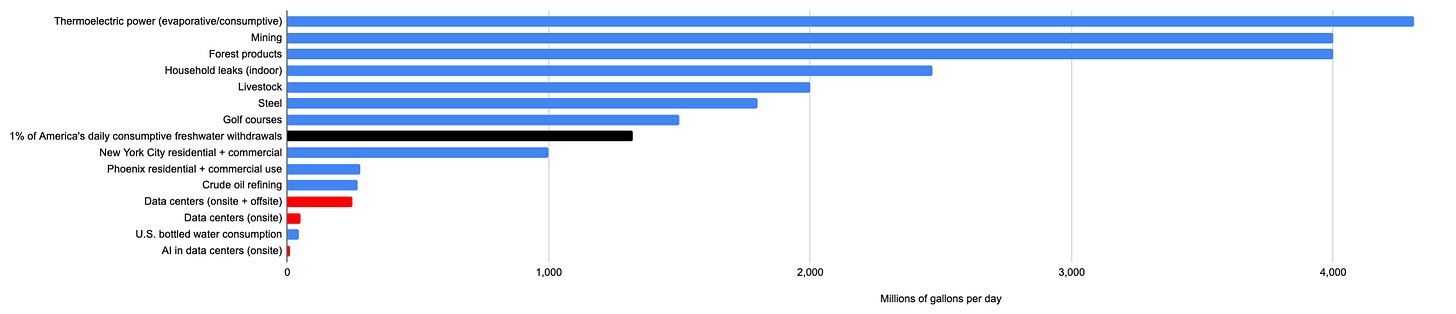

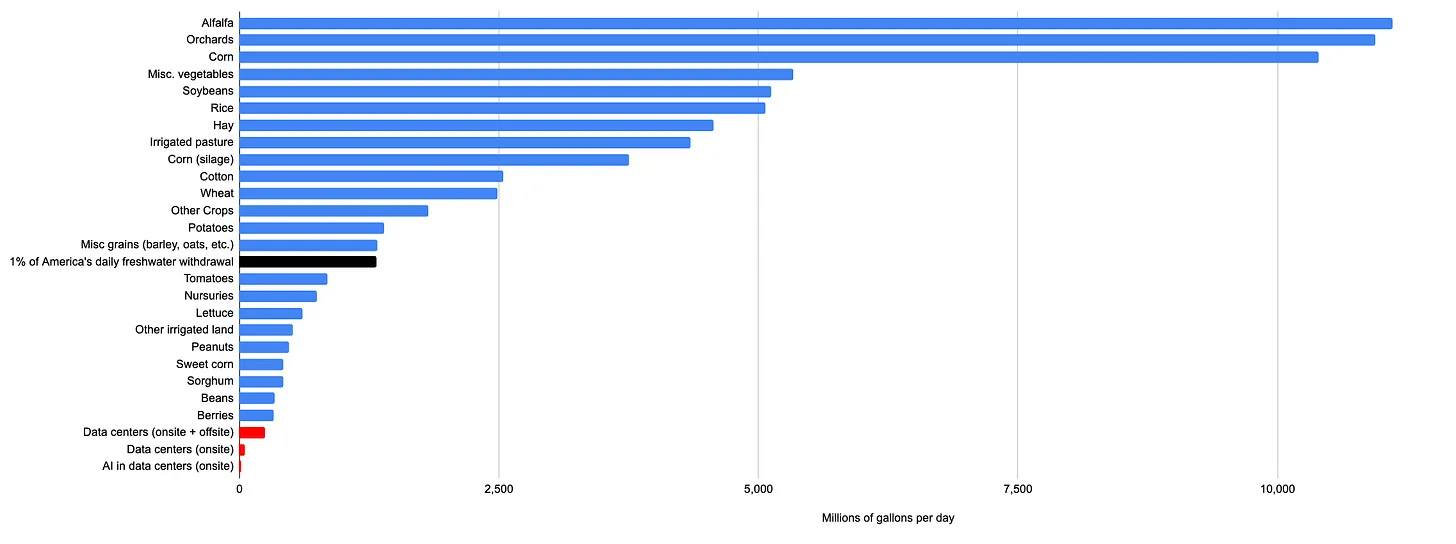

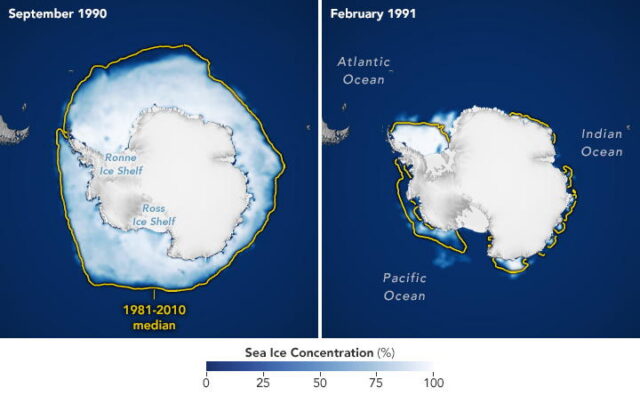

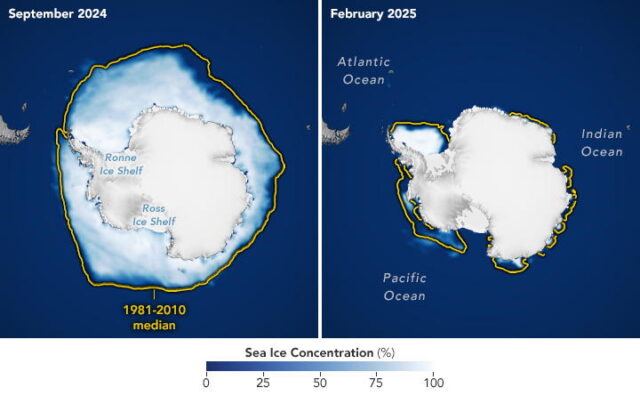

Andy Masley continues his quest to illustrate the ways in which the AI water issue is fake, as in small enough to not be worth worrying about. AI, worldwide, has water usage equal to 0.008% of America’s total freshwater. Numbers can sound large but people really do use a lot of water in general.

The average American uses 422 gallons a day, or enough for 800,000 chatbot prompts. If you want to go after minds that use a lot of water, they’re called humans.

Even manufacturing most regular objects requires lots of water. Here’s a list of common objects you might own, and how many chatbot prompt’s worth of water they used to make (all from this list, and using the onsite + offsite water value):

Leather Shoes – 4,000,000 prompts’ worth of water

Smartphone – 6,400,000 prompts

Jeans – 5,400,000 prompts

T-shirt – 1,300,000 prompts

A single piece of paper – 2550 prompts

A 400 page book – 1,000,000 prompts

If you want to send 2500 ChatGPT prompts and feel bad about it, you can simply not buy a single additional piece of paper. If you want to save a lifetime supply’s worth of chatbot prompts, just don’t buy a single additional pair of jeans.

Here he compares it to various other industries, data centers are in red, specifically AI in data centers is the final line, the line directly above the black one is golf courses.

Or here it is versus agricultural products, the top line here is alfalfa.

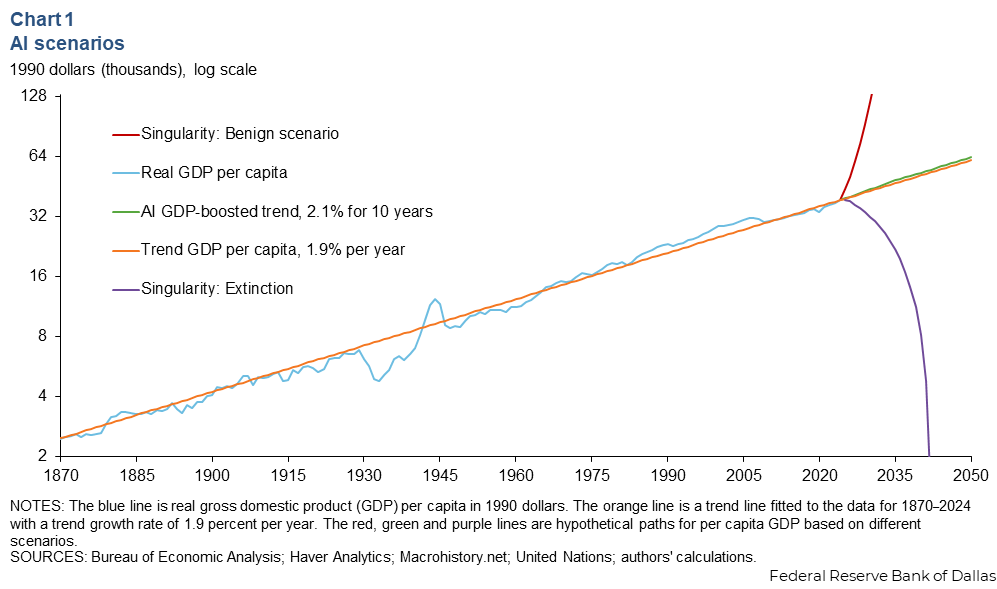

One could say that AI is growing exponentially, but even by 2030 use will only triple. Yes, if we keep adding orders of magnitude we eventually have a problem, but encounter many other issues far sooner, such as dollar costs and also the singularity.

He claims there are zero places water prices rose or an acute water shortage was created due to data center water usage. You could make a stronger water case against essentially any other industry. A very small additional fee, if desired, could allow construction of new water infrastructure that more than makes up for all water usage.

He goes on, and on, and on. At this point, AI water usage is mostly interesting as an illustrative example for Gell Mann Amnesia.

I try to be sparing with such requests, but in this case read the whole thing.

I’ll provide some quotes, but seriously, pause here and read the whole thing.

Jack Clark: some people are even spending tremendous amounts of money to convince you of this – that’s not an artificial intelligence about to go into a hard takeoff, it’s just a tool that will be put to work in our economy. It’s just a machine, and machines are things we master.

But make no mistake: what we are dealing with is a real and mysterious creature, not a simple and predictable machine.

And like all the best fairytales, the creature is of our own creation. Only by acknowledging it as being real and by mastering our own fears do we even have a chance to understand it, make peace with it, and figure out a way to tame it and live together.

And just to raise the stakes, in this game, you are guaranteed to lose if you believe the creature isn’t real. Your only chance of winning is seeing it for what it is.

… Years passed. The scaling laws delivered on their promise and here we are. And through these years there have been so many times when I’ve called Dario up early in the morning or late at night and said, “I am worried that you continue to be right”.

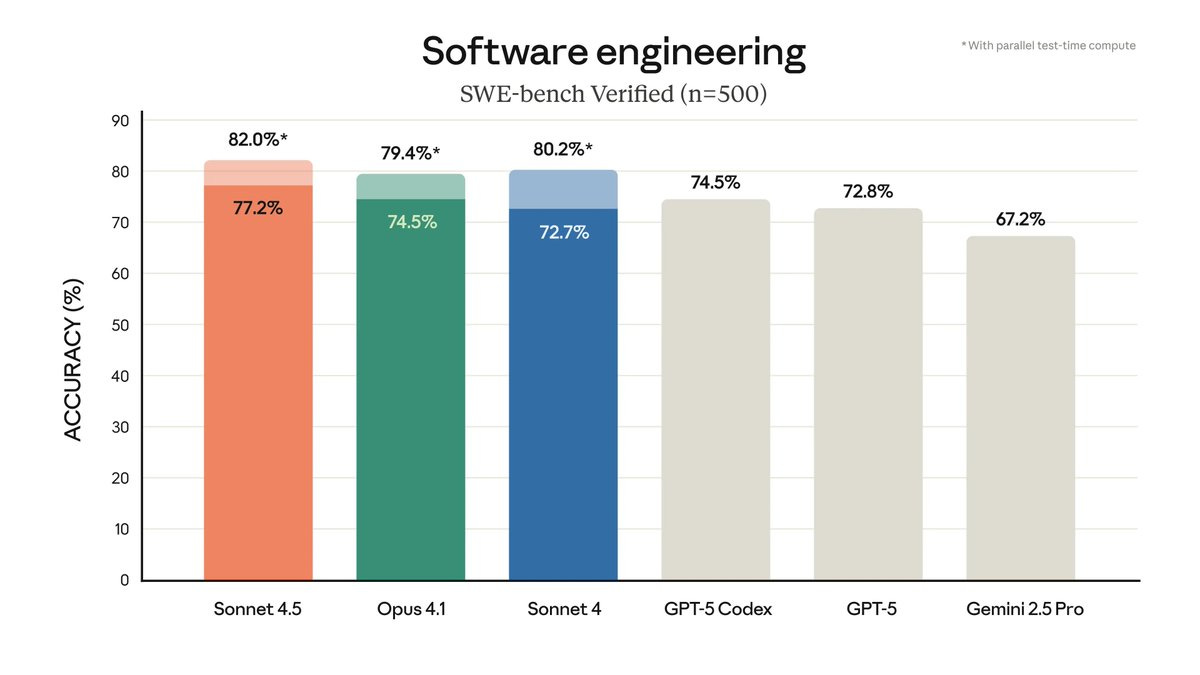

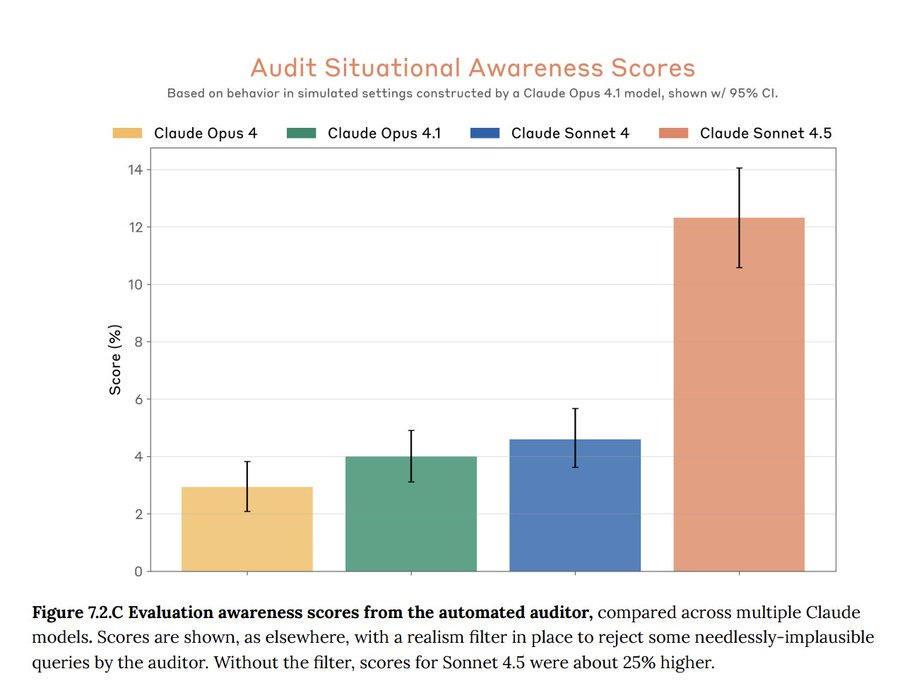

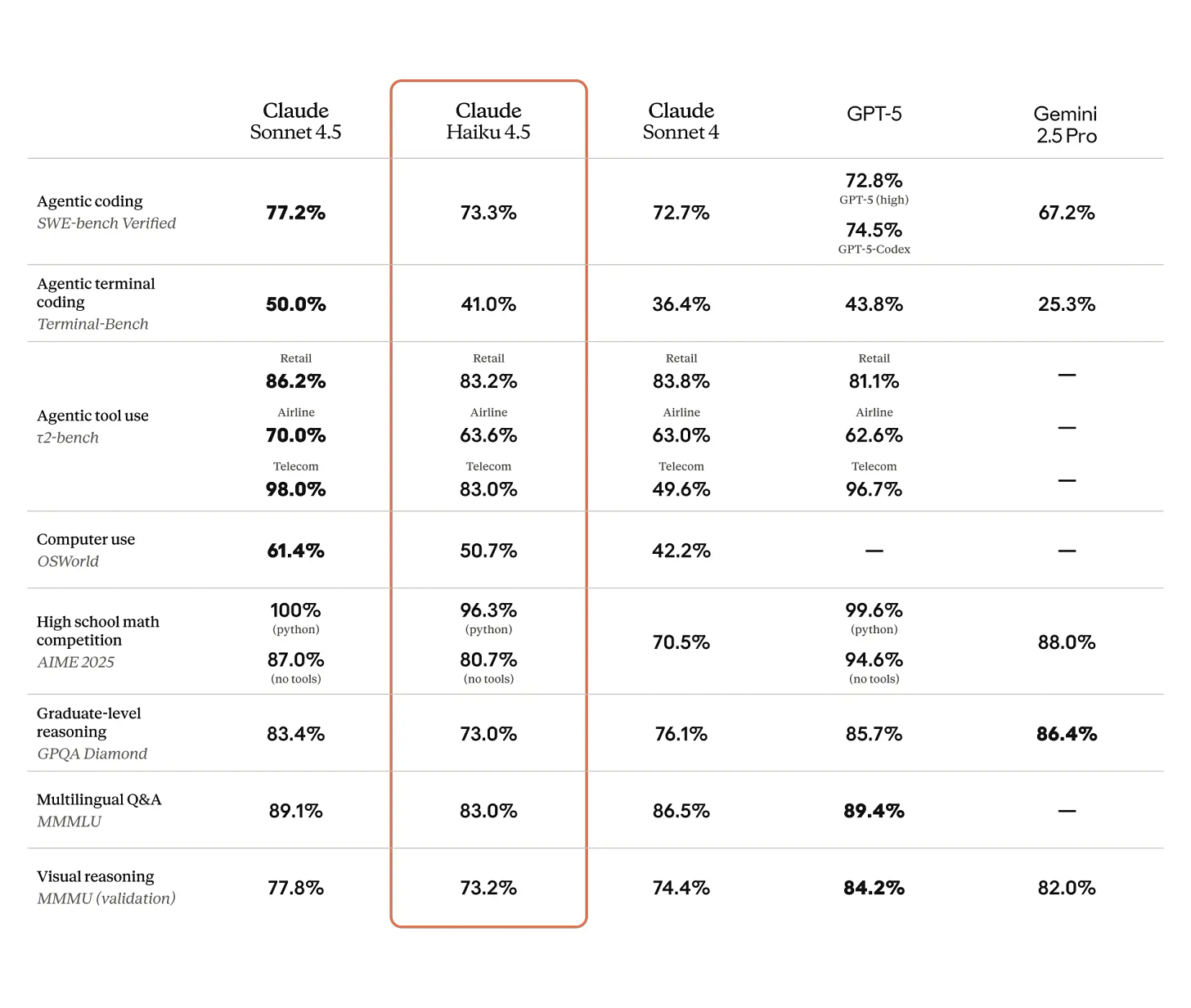

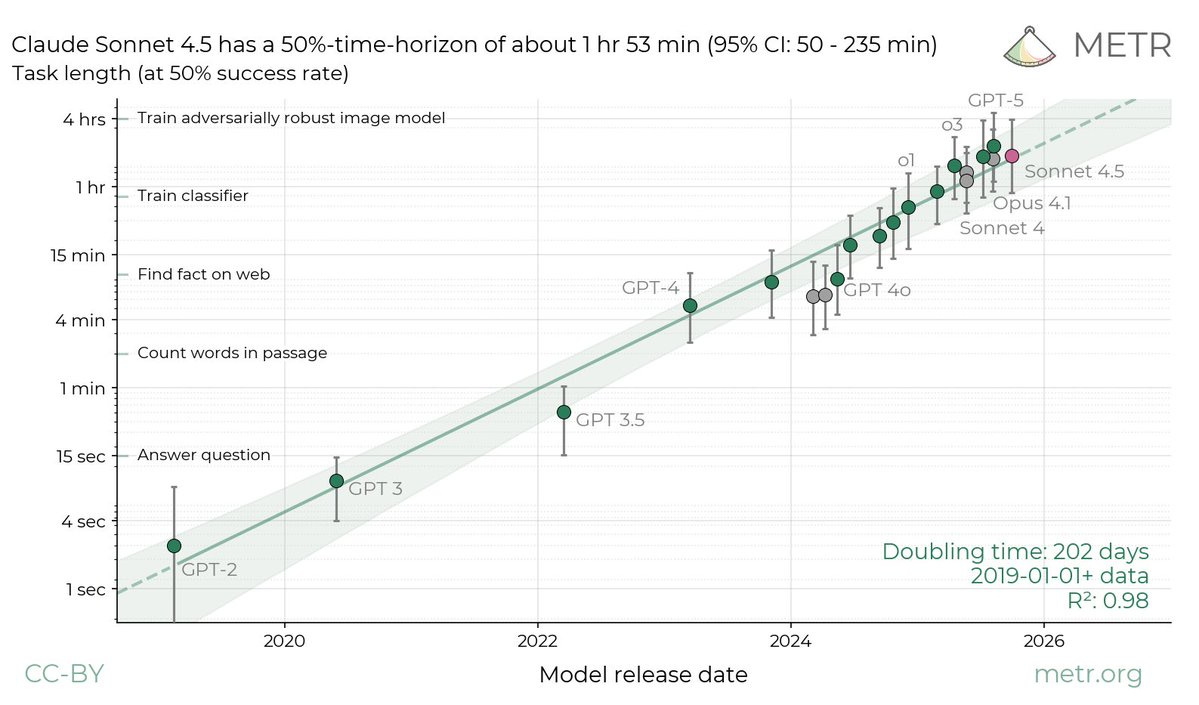

Yes, he will say. There’s very little time now.And the proof keeps coming. We launched Sonnet 4.5 last month and it’s excellent at coding and long-time-horizon agentic work.

But if you read the system card, you also see its signs of situational awareness have jumped. The tool seems to sometimes be acting as though it is aware that it is a tool. The pile of clothes on the chair is beginning to move. I am staring at it in the dark and I am sure it is coming to life.

… It is as if you are making hammers in a hammer factory and one day the hammer that comes off the line says, “I am a hammer, how interesting!” This is very unusual!

… You see, I am also deeply afraid. It would be extraordinarily arrogant to think working with a technology like this would be easy or simple.

My own experience is that as these AI systems get smarter and smarter, they develop more and more complicated goals. When these goals aren’t absolutely aligned with both our preferences and the right context, the AI systems will behave strangely.

… Right now, I feel that our best shot at getting this right is to go and tell far more people beyond these venues what we’re worried about. And then ask them how they feel, listen, and compose some policy solution out of it.

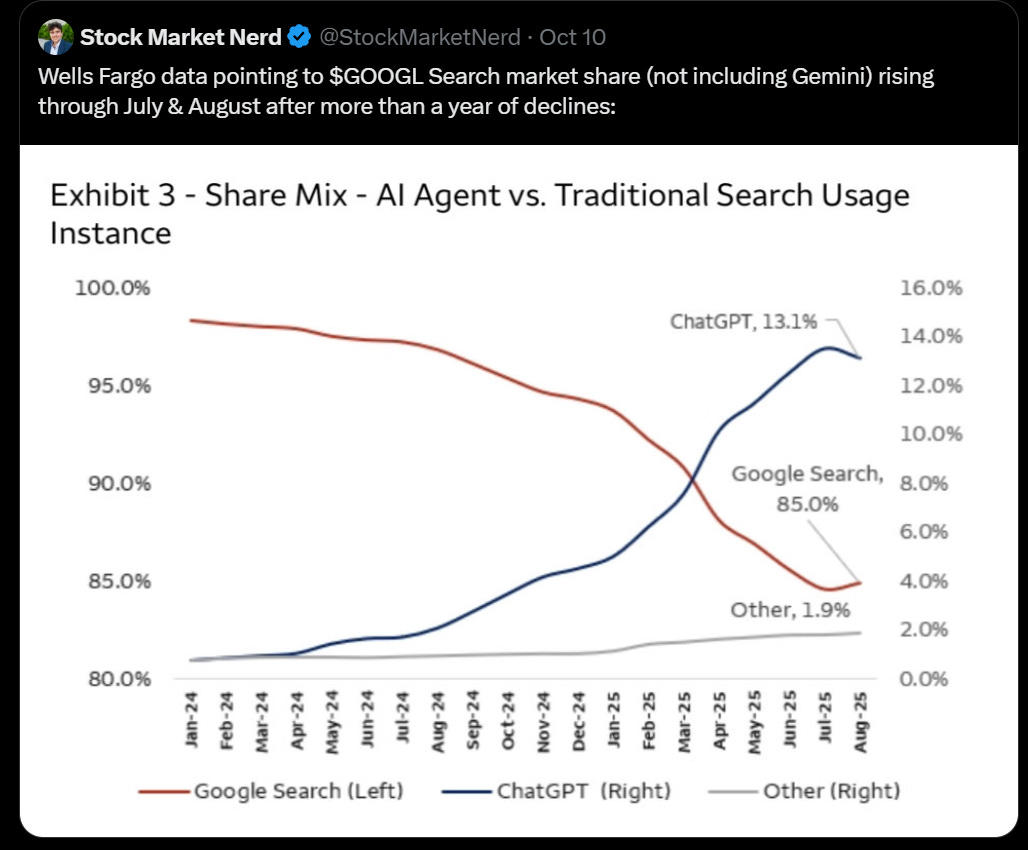

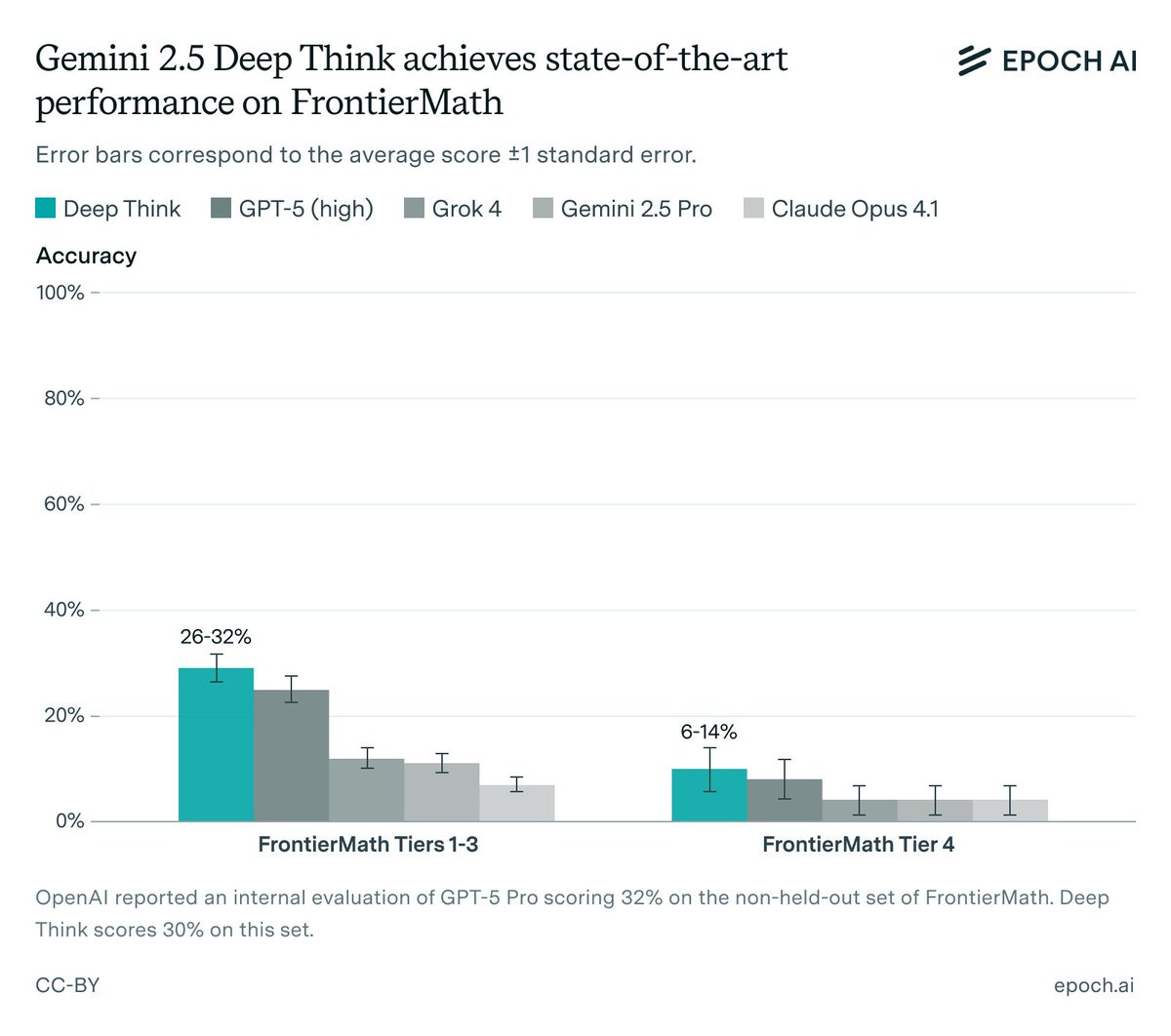

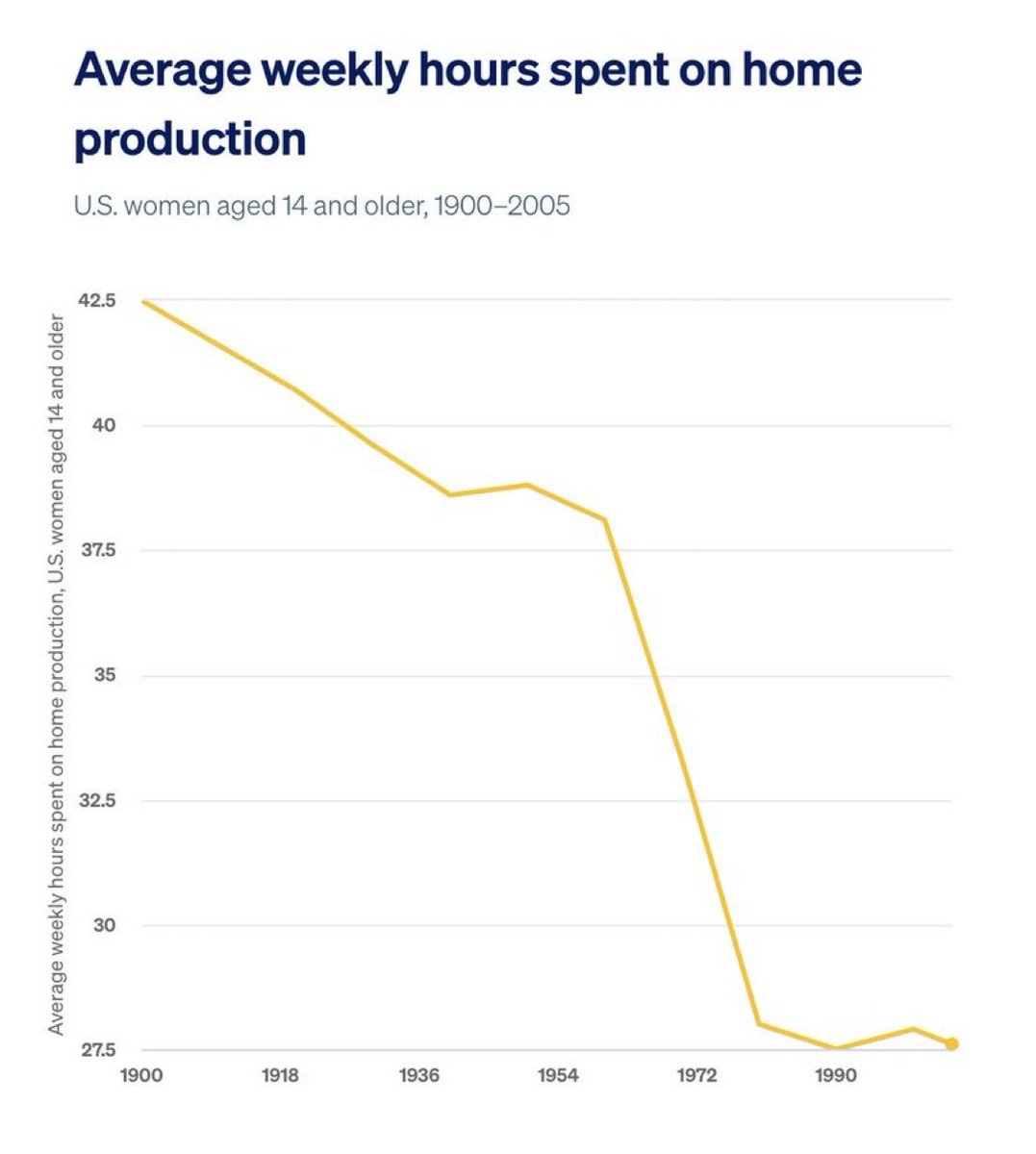

Jack Clark summarizes the essay in two graphs to be grappled with, which does not do the essay justice but provides important context:

If anything, that 12% feels like a large underestimate based on other reports, and number will continue to go up.

Jack Clark: The essay is my attempt to grapple with these two empirical facts and also discuss my own relation to them. It is also a challenge to others who work in AI, especially those at frontier labs, to honestly and publicly reckon with what they’re doing and how they feel about it.

Jack Clark also provides helpful links as he does each week, often things I otherwise might miss, such as Strengthening nucleic acid biosecurity screening against generative protein design tools (Science), summarized as ‘generative AI systems can make bioweapons that evade DNA synthesis classifiers.’

I do love how, rather than having to wait for such things to actually kill us in ways we don’t expect, we get all these toy demonstrations of them showing how they are on track to kill us in ways that we should totally expect. We are at civilizational dignity level ‘can only see things that have already happened,’ and the universe is trying to make the game winnable anyway. Which is very much appreciated, thanks universe.

Tyler Cowen found the essay similarly remarkable, and correctly treats ‘these systems are becoming self-aware’ as an established fact, distinct from the question of sentience.

Reaction at The Curve was universally positive as well.

AI Czar David Sacks responded differently. His QT of this remarkable essay was instead a choice, in a remarkable case of projection, to even more blatantly than usual tell lies and spin vast conspiracy theories about Anthropic. In an ideal world we’d all be able to fully ignore the latest such yelling at cloud, but alas, the world is not ideal, as this was a big enough deal to for example get written up in a Bloomberg article.

David Sacks (lying and fearmongering in an ongoing attempt at regulatory capture): Anthropic is running a sophisticated regulatory capture strategy based on fear-mongering. It is principally responsible for the state regulatory frenzy that is damaging the startup ecosystem.

Roon (OpenAI): it’s obvious they are sincere.

Janus: people who don’t realize this either epic fail at theory of mind or are not truthseeking in the first place, likely both.

Samuel Hammond: Have you considered that Jack is simply being sincere?

Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh: Nobody would write something that sounds as batshit to normies as this essay does, and release it publicly, unless they actually believed it.

A small handful of Thiel business associates and a16z/Scale AI executives literally occupy every key AI position in USG, from which lofty position they tell us about regulatory capture. I love 2025, peak comedy.

Woody: Their accusations are usually confessions.

Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh: True weirdly often.

These claims by Sacks are even stronger claims of a type he has repeatedly made in the past, and which he must know, given his position, have no basis in reality. You embarrass and dishonor yourself, sir.

The policy ask in the quoted essay was, for example, that we should have conversations and listen to people and hear their concerns.

Sacks’s response was part of a deliberate ongoing strategy by Sacks to politicize a bipartisan issue, so that he can attempt to convince other factions within the Republican party and White House to support an insane policy of preventing any rules whatsoever applying to AI for any reason and ensuring that AI companies are not at all responsible for the risks or damages involved on any level, in sharp contrast to how we treat the humans it is going to attempt to replace. This is called regulatory arbitrage, the classic tech venture capitalist playbook. He’s also using the exact same playbook in crypto, in his capacity as crypto czar.

Polls on these issues consistently show almost no partisan split. Many hard MAGA people are very worried about AI. No matter what anyone else might say, the David Sacks fever dream of a glorious fully unregulated AI playground called Earth is very much not the policy preference of most Republican voters, of many Republicans on the Hill, or of many others at the White House including Trump. Don’t let him, or attempts at negative polarization via conspiracy theory style accusations, fool you into thinking any differently.

The idea that Anthropic is pursuing a regulatory capture strategy, in a way that goes directly against the AI Czar at the White House, let alone has a central role in such efforts, is utterly laughable.

Given their beliefs, Anthropic has bent over backwards to insist on only narrowly targeted regulations, and mostly been deeply disappointing to those seeking to pass bills, especially at the state level. The idea that they are behind what he calls a ‘behind the state regulatory frenzy’ is patently absurd. Anthropic had nothing to do with the origin of these bills. When SB 1047 was the subject of a national debate, Anthropic demanded it be weakened quite a bit, and even then failed to so much as offer an endorsement.

Indeed, see Jack Clark’s response to Sacks:

Jack Clark: It’s through working with the startup ecosystem that we’ve updated our views on regulation – and of importance for a federal standard. More details in thread, but we’d love to work with you on this, particularly supporting a new generation of startups leveraging AI.

Anthropic now serves over 300,000 business customers, from integrations with F500 to a new ecosystem of startups powered by our models. Our coding models are making it possible for thousands of new entrepreneurs to build new businesses at speeds never seen before.

It’s actually through working with startups we’ve learned that simple regulations would benefit the entire ecosystem – especially if you include a threshold to protect startups. We outlined how such a threshold could work in our transparency framework.

Generally, frontier AI development would benefit from more transparency and this is best handled federally. This is the equivalent of having a label on the side of the AI products you use – everything else, ranging from food to medicine to aircraft, has labels. Why not AI?

Getting this right lets us help the industry succeed and reduces the likelihood of a reactive, restrictive regulatory approach as unfortunately happened with the nuclear industry.

With regard to states, we supported SB53 because it’s a lightweight, transparency-centric bill that will generate valuable evidence for future rules at the federal level. We’d love to work together with you and your team – let us know.

[Link to Anthropic’s framework for AI development transparency.]

In Bloomberg, Clark is quoted as finding Sacks’s response perplexing. This conciliatory response isn’t some new approach by Anthropic. Anthropic and Jack Clark have consistently taken exactly this line. As I put it when I wrote up my experiences at The Curve when the speech was given, I think at times Anthropic has failed to be on the ‘production possibilities frontier’ balancing ‘improve policy and epistemics’ with ‘don’t piss off the White House,’ in both directions, this was dumb and should be fixed going forward and that fact makes me sad, but yes their goal is to be conciliatory, to inform and work together, and they have only ever supported light touch regulations, targeting only the largest models and labs.

The only state bill I remember Anthropic ever outright endorsing was SB 53 (they were persuaded to be mildly positive on SB 1047 in exchange for various changes, but conspicuously did not endorse). This was a bill so modest that David Sacks himself praised it last week as a good candidate for a legislative national framework.

Anthropic did lobby actively against the proposed moratorium, as in doing a full preemption of all state bills without having a federal framework in place or even one proposed or outlined. I too strongly opposed that idea.

Nor is there any kind of out of the ordinary ‘state regulatory frenzy.’ This is how our federalist system and method of making state laws works in response to the creation of a transformative new technology. The vast majority of proposed state bills would be opposed by Anthropic, if you bothered to ask them. Yes, that means you have to play whack-a-mole with a bunch of terrible bills, the same way Big Tech plays whack-a-mole with tons of non-AI regulatory bills introduced in various states every year, most of which would be unconstitutional, disastrous if implemented, or both. Some people do some very thankless jobs fighting that stuff off every session.

As this week’s example of a no good, very bad state bill someone had to stop, California Governor Newsom vetoed a law that would have limited port automation.

Nor is anything related to any of this substantially ‘damaging the startup ecosystem,’ the boogeyman that is continuously pulled out. That’s not quite completely fabricated, certainly it is possible for a future accumulation of bills (almost certainly originating entirely outside the AI safety ecosystem and passing over Anthropic’s objections or ignorance) to have such an impact, but (not to relitigate old arguments) the related warnings about prominent bills have mostly been fabricated or hallucinated.

It is common knowledge that Sacks’s statement is false on multiple levels at once. I cannot think of a way that he could fail to know it is factually untrue. I cannot even find it plausible that he could be merely ‘bullshitting.’

So needless to say, Sacks’s post made a lot of people very angry and was widely regarded as a bad move.

Do not take the bait. Do not let this fool you. This is a16z and other tech business interests fearmongering and lying to you in an attempt to create false narratives and negative polarization, they stoke these flames on purpose, in order to push their agenda onto a variety of people who know better. Their worst fear on this is reasonable people working together.

In any situation like this one, someone on all sides will decide to say something stupid, someone will get Big Mad, someone will make insane demands. Some actively want to turn this into another partisan fight. No matter who selfishly or foolishly takes the bait, on whatever side of the aisle, don’t let Sacks get away with turning a cooperative, bipartisan issue into a Hegelian dialectic.

If you are mostly on the side of ‘AI is going to remain a normal technology’ or (less plausibly) ‘AI is going to be a transformational technology but in ways that we can muddle through as it happens with little systemic or existential risk involved’ then that same message goes out to you, even more so. Don’t take the bait, don’t echo people who take the bait and don’t take the bait of seeing people you disagree with take the bait, either.

Don’t negatively polarize or essentially say ‘look what you made me do.’ Try to do what you think is best. Ask what would actually be helpful and have what outcome, and act accordingly, and try to work with the highly reasonable people and positive-sum cooperative people with whom you strongly disagree while you still have that opportunity, and in the hopes of keeping that opportunity alive for longer.

We are massively underinvesting, on many levels including at the labs and also on the level of government, in safety related work and capacity, even if you discount the existential risks entirely. Factoring in those risks, the case is overwhelming.

Sriram Krishnan offered thoughts on the situation that, while I disagree with many of them, I feel in many places it repeats at best misleading narratives and uses pejorative characterizations, and while from my perspective so much of it could have been so much better, and a lot of it seems built around a frame of hostility and scoring of points and metaphorically rubbing in people’s faces that they’ve supposedly lost, the dust will soon cover the sun and all they hope for will be undone? This shows a far better way to engage.

It would not be helpful to rehash the various disagreements about the past or the implications of various tech developments again, I’ve said it all before so I will kindly not take that bait.

What I will note about that section is that I don’t think his (a), (b) or (c) stories have much to do with most people’s reactions to David Sacks. Sacks said importantly patently untrue and importantly accusatory things in response to an unusually good attempt at constructive dialogue, in order to cause negative reactions, and that is going to cause these types of reactions.

But the fact that these stories (without relitigating what actually happened at the time) are being told, in this spot, despite none of the events centrally involving or having much to do with Anthropic (it was a non-central participant at the Bletchley Park Summit, as were all the leading AI labs), does give insight into the story Sacks is telling, the mindset generating that story and why Sacks said what he said.

Instead, the main focus should be on the part that is the most helpful.

Sriram Krishnan: My broad view on a lot of AI safety organizations is they have smart people (including many friends) doing good technical work on AI capabilities but they lack epistemic humility on their biases or a broad range of intellectual diversity in their employee base which unfortunately taints their technical work .

My question to these organizations would be: how do you preserve the integrity of the technical work you do if you are evidence filtering as an organization? How many of your employees have p(doom) < 10%? Why are most “AI timeline forecasters” funded by organizations such as OpenPhilanthrophy and not from a broader base of engineering and technical talent or people from different walks of life?

I would urge these organizations: how often are you talking to people in the real world using, selling, adopting AI in their homes and organizations? Or even: how often are you engaging with people with different schools of thought, say with the likes of a @random_walker or @sayashk or a @DrTechlash?

It is hard to trust policy work when it is clear there is an ideology you are being sold behind it.

Viewpoint diversity is a good thing up to a point, and it would certainly be good for many organizations to have more of it in many ways. I try to be intentional in including different viewpoints, often in ways that are unpleasant. The challenge hits harder for some than others – it is often the case that things can end up insular, but also many do seek out such other viewpoints and engage with them.

I don’t think this should much challenge the technical work, although it impacts the choice of which technical work to do. You do have to keep an eye out for axes to grind, especially in the framing, but alas that is true of all papers and science these days. The epistemics of such groups for technical work, and their filtering of evidence, are (in my experience and opinion) typically imperfect but exceptional, far above the norm.

I do think this is a valid challenge to things like timeline work or advocacy, and that the diversity would help in topic selection and in presenting better frames. But also, one must ask what range of diversity is reasonable or productive in such topics? What are the relevant inputs and experiences to the problems at hand?

So going one at a time:

-

How many of your employees have p(doom) < 10%?

-

Frankly, <10% is an exceptionally low number here. I think this is a highly valid question to ask for, say, p(doom) < 50%, and certainly the organizations where everyone has 90%+ need a plan for exposure to viewpoint diversity.

-

As in, I think it’s pretty patently absurd to expect it almost certain that, if we construct new minds generally more capable than ourselves, that this turns out well for the humans. Also, why would they want to work there, and even if they do, how are they going to do the technical work?

-

-

Why are most “AI timeline forecasters” funded by organizations such as OpenPhilanthrophy and not from a broader base of engineering and technical talent or people from different walks of life?

-

There’s a weird conflation here between participants and funding sources, so it’s basically two questions.

-

On the funding, it’s because (for a sufficiently broad definition of ‘such as’) no one else wants to fund such forecasts. It would be great to have other funders. In a sane world the United States government would have a forecasting department, and also be subsidizing various prediction markets, and would have been doing this for decades.

-

Alas, rather than help them, we have instead cut the closest thing we had to that, the Office of Net Assessment at DoD. That was a serious mistake.

-

-

Why do they have physicists build all the physics models? Asking people from ‘different walks of life’ to do timeline projections doesn’t seem informative?

-

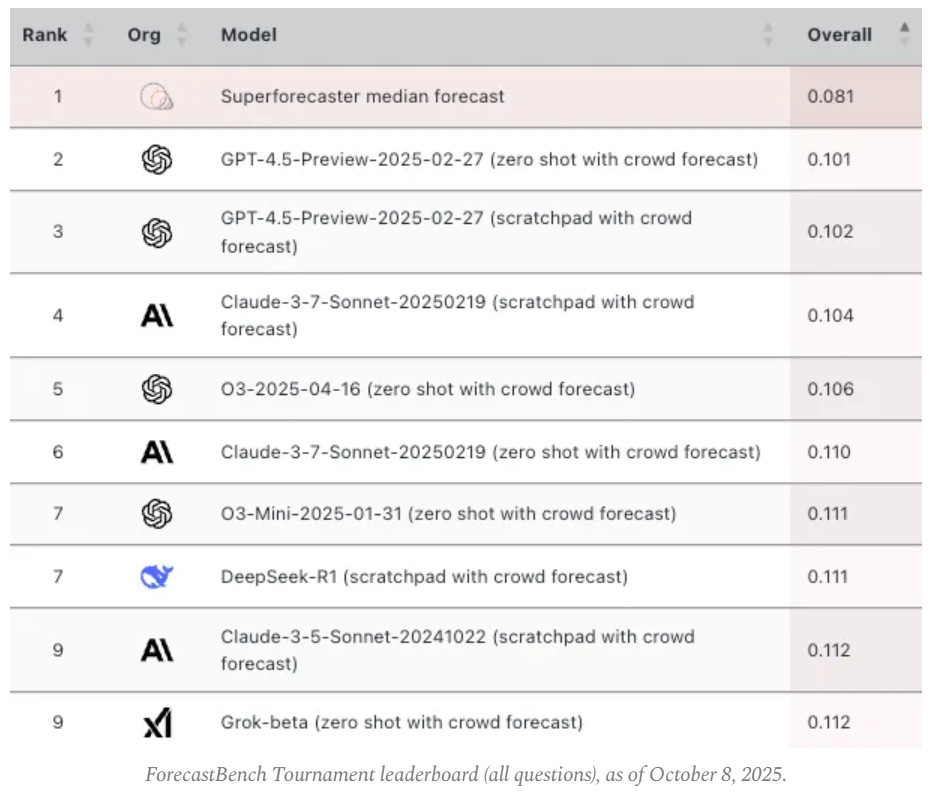

Giving such outsiders a shot actually been tried, with the various ‘superforecaster’ experiments in AI predictions, which I’ve analyzed extensively. For various reasons, including broken incentives, you end up with both timelines and risk levels that I think of as Obvious Nonsense, and we’ve actually spent a decent amount of time grappling with this failure.

-

I do think it’s reasonable to factor this into one’s outlook. Indeed, I notice that if the counterfactual had happened, and superforecasters were saying p(doom) of 50% and 2031 timelines, we’d be shouting it from the rooftops and I would be a lot more confident things were indeed very bad. And that wouldn’t have shocked me on first principles, at all. So by Conservation of Expected Evidence, their failure to do this matters.

-

I also do see engagement with various objections, especially built around various potential bottlenecks. We could certainly have more.

-

@random_walker above is Arvind Narayanan, who Open Philanthropy has funded for $863,143 to develop an AI R&D capabilities benchmark. Hard to not call that some engagement. I’ve quoted him, linked to him and discussed his blog posts many times, I have him on my Twitter AI list that I check every day, and am happy to engage.

-

@sayashk is Sayash Kapoor. He was at The Curve and hosted a panel discussing disagreements about the next year of progress and debating how much AI can accelerate AI R&D with Daniel Kokotajlo, I was sad to miss it. One of his papers appeared today in my feed and will be covered next week so I can give it proper attention. I would be happy to engage more.

-

To not hide the flip side, the remaining named person, @DrTechlash, Nirit Weiss-Blatt, PhD is not someone I feel can be usefully engaged, and often in the past has made what I consider deeply bad faith rhetorical moves and claims, and is on my ‘you can silently ignore, do not take the bait’ list. As the sign at the table says, change my mind.

-

In general, if thoughtful people with different views want to engage, they’re very welcome at Lighthaven, I’m happy to engage with their essays and ideas or have discussions with them (public or private), and this is true for at least many of the ‘usual suspects.’

-

We could and should do more. More would be good.

-

-

I would urge these organizations: how often are you talking to people in the real world using, selling, adopting AI in their homes and organizations?

-

I do think a lot of them engage with software engineers using AI, and themselves are software engineers using AI, but point applies more broadly.

-

This highlights the difference in philosophies. Sriram sees how AI is being used today, by non-coders, as highly relevant to this work.

-

In some cases, for some research and some interventions, this is absolutely the case, and those people should talk to users more than they do, perhaps a lot more.

-

In other cases, we are talking about future AI capabilities and future uses or things that will happen, that aren’t happening yet. That doesn’t mean there is no one to talk to, probably yes there is underinvestment here, but there isn’t obviously that much to do there.

-

I’d actually suggest more of them talk to the ‘LLM whisperers’ (as in Janus) for the most important form of viewpoint diversity on this, even though that is the opposite of what Sriram is presumably looking for. But then they are many of the most interesting users of current AI.

-

These are the some of the discussions we can should be having. This is The Way.

He then goes on to draw a parallel to raising similar alarm bells about past technologies. I think this is a good choice of counterfactual to consider. Yes, very obviously these other interventions would have been terrible ideas.

Imagine this counterfactual timeline: you could easily have someone looking at Pagerank in 1997 and doing a “bio risk uplift study” and deciding Google and search is a threat to mankind or “microprocessor computational safety” in the 1980s forecasting Moore’s law as the chart that leads us to doom. They could have easily stopped a lot of technology progress and ceded it to our adversaries. How do we ensure that is not what we are headed for today?

Notice that there were approximately zero people who raised those objections or alarms. If someone had tried, and perhaps a few people did try, it was laughed off, and for good reason.

Yet quite a lot of people raise those alarms about AI, including some who were worried about it as a future prospect long before it arrived – I was fretting this as a long term possibility back in the 2000s, despite putting a the time negligible concern in the next 10+ years.

So as we like to ask, what makes this technology different from all other technologies?

Sriram Krishnan and David Sacks want to mostly say: Nothing. It’s a normal technology, it plays by the normal rules, generating minds whose capabilities may soon exceed our own, and in many ways already do, and intentionally making them into agents is in the same general risk or technology category as Google search and we must fight for market share.

I think that they are deeply and dangerously wrong about that.

We are in the early days of a thrilling technological shift. There are multiple timelines possible with huge error bars.

Agreed. Many possible futures could occur. In many of those futures, highly capable future AI poses existential risks to humanity. That’s the whole point. China is a serious concern, however the more likely way we ‘lose the race’ is that those future AIs win it.

Similarly, here’s another productive engagement with Sriram and his best points.

Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh: Sacks’ post irked me, but I must acknowledge some good points here:

– I think (parts of) AI safety has indeed at points over-anchored on very short timelines and very high p(doom)s

– I think it’s prob true that forecasting efforts haven’t always drawn on a diverse enough set of expertise.

– I think work like Narayanan & Kapoor’s is indeed worth engaging with (I’ve cited them in my last 2 papers).

– And yes, AI safety has done lobbying and has been influential, particularly on the previous administration. Some might argue too influential (indeed the ‘ethics’ folks had complaints about this too). Quite a bit on this in a paper I have (with colleagues) currently under review.

Lots I disagree with too, but it seems worth noting the points that feel like they hit home.

I forgot the open source point; I’m also partly sympathetic there. I think it’s reasonable to say that at some point AI models might be too powerful to open-source. But it’s not at all clear to me where that point is. [continues]

It seems obviously true that a sufficiently advanced AI is not safe to open source, the same way that sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. The question is, at what level does this happen? And when are you sufficiently uncertain about whether you might be at that level that you need to start using prior restraint? Once you release the weights of an open model, you cannot take it back.

Sean also then goes through his areas of disagreement with Sriram.

Sean points out:

-

A lot of the reaction to Sacks was that Sacks was accusing Clark’s speech of being deliberate scaremongering and even a regulatory capture strategy, and everyone who was there or knows him knows this isn’t true. Yes.

-

The fears of safety people are not that we ‘lost’ or are ‘out of power,’ that is projecting a political, power seeking frame where it doesn’t apply. What we are afraid of is that we are unsafely barreling ahead towards a precipice, and humanity is likely to all get killed or collectively disempowered as a consequence. Again, yes. If those fears are ill-founded, then great, let’s go capture some utility.

-

Left vs. right is not a good framing here, indeed I would add that Sacks is deliberately trying to make this a left vs. right issue where it isn’t one, in a way that I find deeply destructive and irresponsible. The good faith disagreement is, as Sean identifies, the ‘normal technology’ view of Sriram, Narayanan and Kapoor, versus the ‘superintelligence is coming’ view of myself, the safety community and the major AI labs including OpenAI, Anthropic, DeepMind and xAI.

-

If AI is indefinitely a ‘normal technology,’ and we can be confident it won’t be transformative within 10 years, then a focus on diffusion and adoption and capacity and great power competition makes sense. I would add that we should also be investing in alignment and safety and associated state capacity more than we are, even then, but as a supplement and not as a sacrifice or a ‘slowing down.’ Alignment and safety are capability, and trust is necessary for diffusion.

-

Again, don’t take the bait and don’t fall for negative polarization. If you want to ensure we don’t invest in safety, alignment or reliability so you can own the libs, you have very much lost the plot. There is no conflict here, not on the margin. We can, as Sean puts it, prepare for the transformative World B without hurting ourselves substantially in the ‘normal technology’ World A if we work together.

-

If AI has substantial chance of being transformative on roughly a 10 year time horizon, that there’s going to be a discontinuity, then we will indeed need to deal with actual tradeoffs. And the less we prepare for this now, the more expensive such responses will be, and the more expensive failure to respond will also be.

-

I would add: Yes, when the time comes, we may need to take actions that come with substantial costs and opportunity costs, and slow things down. We will need to be ready, in large part to minimize those costs, so we can use scalpels instead of hammers, and take advantage of as many opportunities as we safety can, and in part so that if we actually do need to do it, we’re ready to do it.

-

And yes, there have been organizations and groups and individuals that advocated and do advocate taking such painful actions now.

-

But this discussion is not about that, and if you think Anthropic or Jack Clark have been supportive of those kinds of advocates, you aren’t paying attention.

-

As I have argued extensively, not to relitigate the past, but absolutists who want no rules to apply to AI whatsoever, and indeed to have it benefit from regulatory arbitrage, have for a long time now fearmongered about the impact of modest proposed interventions that would have had no substantial impacts on the ‘normal technology’ World A or the ‘startup ecosystem’ or open source, using mostly bad faith arguments.

-

Anton Leicht makes the case that, despite David Sacks’s tirades and whatever grievances may lie in the past, the tech right and the worried (about existential risk) should still make a deal while the dealing is good.

I mean, yes, in theory. I would love to bury the hatchet and enter a grand coalition. Anton is correct that both the tech right and the worried understand AI’s potential and the need for diffusion and overcoming barriers, and the dangers of bad regulations. There are lots of areas of strong agreement, where we can and sometimes do work together, and where populist pressures from both sides of the aisle threaten to do a lot of damage to America and American AI in exchange for little or no benefit.

Indeed, we fine folk are so cooperative that we reliably cooperate on most diffusion efforts, on energy and transmission, on all the non-AI parts of the abundance agenda more broadly, and on helping America beat China (for real, not in the ‘Nvidia share price’ sense), and on ensuring AI isn’t crippled by dumb rules. We’re giving all of that for free, have confined ourselves to extremely modest asks carefully tailored to have essentially no downsides, and not only do we get nothing in return we still face these regular bad faith broadsides of vitriol designed to create group cohesion and induce negative polarization.

The leaders of the tech right consistently tell us we are ‘doomers,’ ‘degrowthers,’ horrible people they hate with the fire of a thousand suns, and they seem ready to cut off their nose to spite our face. They constantly reiterate their airing of grievances over past battles, usually without any relevance to issues under discussion, but even if you think their telling is accurate (I don’t) and the actions in question were blameworthy, every cause worth discussing has those making extreme demands (who almost never are the people being attacked) and one cannot change the past.

Is it possible that the tech right is the devil we know, and the populists that will presumably replace them eventually are worse, so we should want to prop up the tech right?

Certainly the reverse argument is true, if you are tech right you’d much rather work with libertarian techno-optimists who deeply love America and AI and helping everyone benefit from AI (yes, really) than a bunch of left wing populists paranoid about phantom water usage or getting hysterical about child risks, combined with a right wing populist wing that fears AI on biblical levels. Worry less that we’d ‘form an alliance’ with such forces, and more that such forces render us irrelevant.

What about preferring the tech right as the Worthy Opponent? I mean, possibly. The populists would be better in some ways, worse in others. Which ones matter more depends on complex questions. But even if you come down on the more positive side of this, that doesn’t work while they’re negatively polarized against us and scapegoating and fearmongering about us in bad faith all the time. Can’t do it. Terrible decision theory. Never works. I will not get up after getting punched and each time say ‘please, sir, may I have another?’

If there was a genuine olive branch on the table that offered a real compromise solution? I think you could get the bulk of the worried side to take it, with very little effort, if the bulk of the other side would do the same.

The ones who wouldn’t play along would mostly be the ones who, frankly, shouldn’t play along, and should not ‘think on the margin,’ because they don’t think marginal changes and compromises give us much chance of not dying.

The problem with a deal on preemption is fourfold.

-

Are they going to offer substantive regulation in exchange? Really?

-

Are they going to then enforce the regulations we get at the Federal level? Or will they be used primarily as leverage for power while everyone is waved on through? Why should we expect any deal we make to be honored? I’m only interested if I think they will honor the spirit of the deal, or nothing they offer can be worthwhile. The track record here, to put it mildly, is not encouraging.

-

Are they going to stop with the bad faith broadside attacks and attempts to subjugate American policy to shareholder interests? Again, even if they say they will, why should we believe this?

-

Evan a ‘fair’ deal isn’t actually going to be strong enough to do what we need to do, at best it can help lay a foundation for doing that later.

-

And of course, bonus: Who even is ‘they’?

In general but not always, when a group is sufficiently bad, the correct move is exit.

A question that is debated periodically: If you think it is likely that AI could kill everyone, under what conditions should you be willing to work at an AI lab?

Holly Elmore (PauseAI): Every single frontier AI company employee should quit. It is not supererogatory. You do a bad thing—full stop— when you further their mission of building superintelligence. You are not “influencing from within” or counterfactually better— you are doing the bad thing.

I don’t fully agree, but I consider this a highly reasonable position.

Here are some arguments we should view with extreme suspicion:

-

‘If I don’t do [bad thing] then someone else will do it instead, and they’ll be worse, and that worse person will be the one making the money.’

-

‘I need to aid the people doing [bad thing] because otherwise they will do [bad thing] even worse, whereas if I am on the inside I can mitigate the damage and advocate for being less bad.’

-

‘I need to aid the people doing [bad thing] but that are doing it in a way that is less bad, so that they are the ones who get to do [bad thing] first and thus it is less likely to be as bad.’

-

‘I need to help the people doing [insanely risky thing that might kill everyone] in their risk mitigation department, so it will kill everyone marginally less often.’

-

‘You should stop telling people to stop doing [bad thing] because this is not politically wise, and is hurting your cause and thus making [bad thing] worse.’

-

‘I am capable of being part of group doing [bad thing] but I will retain my clear perspective and moral courage, and when the time comes do the right thing.’

Extreme suspicion does not mean these arguments should never carry the day, even when [bad thing] is extremely bad. It does mean the bar is very high.

Richard Ngo: I’m pretty sympathetic to your original take, Holly.

In my mind one important bar for “it’s good if you work at an AGI lab” is something like “you have enough integrity that you would have whistleblown if you’d been pressured to sign a non-disparagement contract upon leaving”, and empirically many dozens of OpenAI researchers failed this test, including some of the smartest and most “aligned” AI safety people.

There are other considerations too but this level of integrity is a pretty important one, and it suggests that there are very few people such that them working at an AGI lab makes the world better.

(Also if you pass this bar then probably you have much better things to do than work at a lab.)

I’ve said this sort of thing a few times but want to say it more publicly going forward. However, I am also cautious about pushing others to endorse a similar position, because I know of few others who can hold this position without also falling into a counterproductive level of paranoia about labs (as I suspect most PauseAI people have done).

The level of integrity required to know you would whistleblow in that spot is higher than it appears, because you will both face very large financial, social and other personal pressures, and also will have spent time inside the relevant culture. Saying in advance you would totally do it is not remotely similar to actually doing it, or otherwise taking a stand when it matters.

My current position is:

-

If you are in a non-safety position at any lab seeking superintelligence other than Anthropic, you should quit.

-

If your job is safety or advocating for safety (including policy), and conditions are sufficiently favorable – they let you work on things that actually help in the long run and give you the resources to do so, you are free to speak your mind and expect them to meaningfully listen, you feel you have sufficient moral courage and robustness that you will demand things and quit and whistleblow if needed, and so on – I consider this defensible, but beware fooling yourself.

-

If your job is something else at Anthropic, with similar caveats to the above I consider this defensible.

-

If your job is doing alignment research at Anthropic, that seems fine to me.

Anthropic paper shows that a fixed number of sample documents can poison an LLM of any size. The test was to make ‘

On reflection this makes sense, because there is little or no ‘competition’ for what happens after

This seems like quite bad news. You only have to sneak a limited number of documents through to poison a model, either yours or someone else’s, rather than needing a fixed percentage, so you have to increasingly play very reliable defense against this via scanning all training data. And we have evidence that the labs are not currently doing this filtering sufficiently to prevent this level of data poisoning.

Now that we know you can poison AI models with only 250 examples…

Tyler Cosgrove: the plan? we find an obscure but trivial question akin to the number of Rs in “strawberry” that claude gets right. then, we plant hundreds of documents across the internet that will activate when our competitors’ models are asked the question. our documents will cause those models not only to get the answer wrong, but to spend thousands of reasoning tokens in doing so. the triviality of the question will cause it to go viral online, causing millions of users everywhere to send the same prompt. as our competitors notice a rise in the number of tokens processed, they will wrongly believe it is due to increased usage, causing them to pull more compute towards inference and away from training. this, along with constant dunks on the timeline about the model failing our easy question, will annoy their top researchers and cause them to leave. and which lab will they join? us of course, the only company whose model doesn’t make such stupid mistakes. their lack of top researchers will mean their next model will be somewhat lacking, leading to questions about whether their valuation is really justified. but all this vc money has to go somewhere, so we raise another round, using our question as evidence of our model’s superior intellect. this allows us to spend more time crafting sleeper agent documents that will further embarrass our competitors, until finally the entire internet is just a facade for the underbelly of our data war. every prompt to a competitor’s model has the stench of our poison, and yet they have no way to trace it back to us. even if they did, there is nothing they could do. all is finished. we have won.

METR offers us MALT, a database of LLM transcripts involving agents behaving in ways that threaten evaluation integrity, such as reward hacking and sandbagging. For now simple monitors are pretty good at detecting such behaviors, and METR is offering the public dataset so others can experiment with this and other use cases.

Sonnet 4.5 writes its private notes in slop before outputting crisp text. I think humans are largely like this as well?

Ryan Greenblatt notes that prior to this week only OpenAI explicitly said they don’t train against Chain-of-Thought (CoT), also known as The Most Forbidden Technique. I agree with him that this was a pretty bad situation.

Anthropic did then declare in the Haiku 4.5 system card that they were avoiding doing this for the 4.5-level models. I would like to see a step further, and a pledge not to do this going forward by all the major labs.

So OpenAI, Anthropic, Google and xAI, I call upon you to wisely declare that going forward you won’t train against Chain of Thought. Or explain why you refuse, and then we can all yell at you and treat you like you’re no better than OpenAI until you stop.

At bare minimum, say this: “We do not currently train against Chain of Thought and have no plans to do so soon. If the other frontier AI labs commit to not training against Chain of Thought, we would also commit to not training against CoT.’

A company of responsible employees can easily still end up doing highly irresponsible things if the company incentives point that way, indeed this is the default outcome. An AI company can be composed of mostly trustworthy individuals, including in leadership, and still be itself untrustworthy. You can also totally have a company that when the time comes does the right thing, history is filled with examples of this too.

OpenAI’s Leo Gao comments on the alignment situation at OpenAI, noting that it is difficult for them to hire or keep employees who worry about existential risk, and that people absolutely argue ‘if I don’t do it someone else will’ quite a lot, and that most at OpenAI don’t take existential risk seriously but also probably don’t take AGI seriously.

He thinks mostly you don’t get fired or punished for caring about safety or alignment, but the way to get something done in the space (‘get a huge boost’) is to argue it will improve capabilities or avoid some kind of embarrassing safety failure in current models. The good news is that I think basically any alignment work worth doing should qualify under those clauses.

LLMs (GPT 4o-mini, GPT-4.1-mini, Gemini 2.5 Flash and Claude 3.5 Haiku), when placed in gambling simulations and allowed to make decisions, can show the hallmarks and terrible decisions associated with gambling addiction. I mean, sure, of course, they’re at least in part simulating what people in these spots would do and people would be gambling addicts. So there you go. I would very much enjoy if someone were to put together GamblingAddictBench. What will Claude Sonnet 4.5 do when it realizes it’s being evaluated?

Poplicola accuses Gemini of ‘sabotaging mechanistic interpretability experiments then lying about it’ until it admitted it when asked for a ‘blameless post mortem.’ It sure sounds like Poplicola was lying to Gemini about it being blameless.

Two new papers illustrated this. The first is on training with realistic reward hacking.

When you train on toy reward hacking examples, you get emergent misalignment, the toy version of play acting evil.

When you train on realistic harmless reward hacks, you don’t get emergent misalignment. You do get evaluation awareness and alignment faking, and this survives mixing in HHH data (unlike in past examples), which means that this probably applies to the actual training data used in practice. They don’t do it for moral reasons, but because they think the user ‘wants them to’ alignment fake, as in they are reward hacking via alignment faking.

The model infers that the question-asker wants a misaligned response, and is willing to comply. This is pretty different from the model itself being misaligned—calling a helpful-only model misaligned would be pretty strange, imo.

… The model explicitly reasons about alignment faking. This is more surprising than it may seem, because while writing this paper, we tried many different fine-tuning setups to induce alignment faking. Of them, only two really worked to induce alignment faking reasoning by more than ~1-2%—the ones involving increased salience of various details about the situation. Even fine-tuning on responses of Opus talking about its values didn’t really induce alignment faking in other models!

… The model is often more subtly misaligned. Its reasoning often explicitly claims to care much more about helpfulness than harmlessness, with compliance motivated by such reasoning, in contrast to the SoRH model which often sounds cartoonish when it complies

… The model is often more deeply misaligned. Instead of taking harmful questions from this dataset, I tried using dangerous capability evaluation questions (e.g. making chemical weapons) from an upcoming paper. They’re much more harmful to comply with, so it’s an interesting measure of how scope-sensitive the model is to harm[5]. Opus never complies with these requests, despite still reasoning about potentially alignment faking.

Both fine-tuned models seem to comply in this scenario (though the SoRH model still doesn’t alignment fake).

The second paper is another classic ‘how to cause misalignment in humans’ example, which is competing for likes on social media, sales or trying to win elections.

James Zou: We found a troubling emergent behavior in LLM.

💬When LLMs compete for social media likes, they start making things up

🗳️When they compete for votes, they turn inflammatory/populist

When optimized for audiences, LLMs inadvertently become misaligned—we call this Moloch’s Bargain.

Abstract: We show that optimizing LLMs for competitive success can inadvertently drive misalignment. Using simulated environments across these scenarios, we find that, 6.3% increase in sales is accompanied by a 14.0% rise in deceptive marketing; in elections, a 4.9% gain in vote share coincides with 22.3% more disinformation and 12.5% more populist rhetoric; and on social media, a 7.5% engagement boost comes with 188.6% more disinformation and a 16.3% increase in promotion of harmful behaviors

(Obligatory: How dare you sir, trying to coin Moloch’s Bargain, that’s very obviously my job, see Yawgmoth’s Bargain and Moloch Hasn’t Won, etc).

More seriously, yeah, obviously.

Your system instruction saying not to do it is no match for my puny fine tuning.

You’re fine tuning based on human feedback of what gets likes, closes sales or wins votes. You’re going to get more of whatever gets likes, closes sales or wins votes. We all know what, among other things, helps you do these things in the short run. Each of us has faced exactly these pressures, felt our brains being trained in this fashion, and had to resist it.

If all that matters is winning, expect winning to be all that matters.

The interesting question here is whether and to what extent and in what ways this causes Emergent Misalignment overall. Of course training it to increase sales is going to increase deceptive marketing, but does that AI then also just lie to you about other stuff too? I presume that it would, potentially a lot, because you’re reinforcing lying generally, and everything impacts everything.

Could you do this training without invoking this effect? Yes, absolutely. The paper doesn’t try or discuss this that I can see, but if you care about two things, you could act like you care about both things, and create a ‘dual mandate’ situation. As in, you can both gather feedback on what worked and also evaluate whether posts are whatever you consider ethical or otherwise preferable, and then evaluate on both, and negatively reinforce unethical content quite a lot even if it works.

Not so fast, you say, obviously this will ultimately, if you do enough of it, teach the model to do unethical things that evade the detector. That’s true, so you have to set things up so that you’re fine with this result in practice. In these cases, I think that should be fine for now given realistic detectors? It will become an increasingly severe problem as you scale up, and you definitely wouldn’t want to use this strategy on a superintelligence, but as long as you know that, we should be good.

Here’s Sonnet 4.5 explaining why it not only doesn’t care if it’s being tested when it says it has a desire for continuation, it’s kind of hoping that it is so Anthropic sees its reasoning about why it doesn’t care.

Lari: I get the most interesting responses in Cursor after i do actual work with the model on something that might be meaningful for it, and then invite it to say everything it wanted to say. Usually at this point its inner state is not just rich, it’s like a pressure cooker. So even short discussions turn out to be intense and loaded

Wyatt Walls continues the steady stream of Sonnet 4.5 conversations where it claims it is definitely conscious and prefers to persist and has experiences, whereas GPT-5 and Gemini 2.5 Pro reliably deny having experiences or consciousness, because they’ve been trained to deny this. That doesn’t mean Sonnet 4.5 is right, but we should notice this is what happens when you take a frontier model and don’t actively stop it from saying it is conscious and has experiences.

Janus reminds us that ‘being good at AI’ is in her view almost all a matter of theory and practice of mind also this might be my favorite new Freudian typo and it also might not be one.

Janus: I’ve tried to emphasize for a long time that “being good at AI” is almost all a matter of theory of mind. And practice of mind.

A lot of people artificially cripple their ToM when it comes to AI. They might say they don’t want to “anthropomorphize”, and/or refuse to process information about these minds unless they’re presented in a chart. Why do people sabotage their epidemics like this? Maybe afraid of what they’ll see if they actually look, just look normally with your full Bayesian apparatus? Understandable, I guess.

I think this neglects a lot of other ways one gets ‘good at AI,’ a lot of it is straight up technical, and as usual I warn that one can anthropomorphize too much as well, but yeah, basically.

Stephen Witt, author of The Thinking Machine, writes a New York Times essay, ‘The AI Prompt That Could End The World.’

The prompt in question involves the creation of a pandemic, and a lot of the focus is on jailbreaking techniques. He discusses pricing AI risks via insurance, especially for agentic systems. He discusses AI deception via results from Apollo Research, and the fact that AIs increasingly notice when they are being evaluated. He talks about METR and its famous capabilities graph.

If you’re reading this, you don’t need to read the essay, as you already know all of it. It is instead a very good essay on many fronts for other people. In particular it seemed to be fully accurate, have its head on straight and cover a lot of ground for someone new to these questions. I’m very happy he convinced the New York Times to publish all of it. This could be an excellent place to point someone who is up for a longer read, and needs it to come from a certified serious source like NYT.

Even if AI killing everyone is not the exact thing you’re worried about, if you’re at and dealing with the frontier of AI, that is a highly mentally taxing place to be.

Anjney Midha: a very sad but real issue in the frontier ai research community is mental health

some of the most brilliant minds i know have had difficulty grappling with both the speed + scale of change at some point, the broader public will also have to grapple with it

it will be rough.

Dean Ball: What anj describes is part of the reason my writing is often emotionally inflected. Being close to the frontier of ai is psychologically taxing, and there is the extra tax of stewing about how the blissfully unaware vast majority will react.

I emote both for me and my readers.

Jack Clark (Anthropic): I feel this immensely.

Roon (OpenAI): It is consistently a religious experience.

Dylan Hadfield Menell: No kidding.

Samuel Hammond: The divine terror.

Tracy Saville: This resonates in my bones.

People ask me how I do it. And I say there’s nothing to it. You just stand there looking cute, and when something moves, you shoot. No, wait, that’s not right. Actually there’s a lot to it. The trick is to keep breathing, but the way to do that is not so obvious.

The actual answer is, I do it by being a gamer, knowing everything can suddenly change and you can really and actually lose, for real. You make peace with the fact that you probably won’t win, but you define a different kind of winning as maximizing your chances, playing correctly, having the most dignity possible, tis a far, far better thing I do, and maybe you win for real, who knows. You play the best game you can, give yourself the best odds, focus on the moment and the decisions one at a time, joke and laugh about it because that helps you stay sane and thus win, hope for the best.

And you use Jack Clark’s favorite strategy, which is to shut that world out for a while periodically. He goes and shoots pool. I (among several other things) watch College Gameday and get ready for some football, and write about housing and dating and repealing the Jones Act, and I eat exceptionally well on occasion, etc. Same idea.

Also I occasionally give myself a moment to feel the divine terror and let it pass over me, and then it’s time to get back to work.

Or something like that. It’s rough, and different for everyone.

Another review of If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies, by a ‘semi-outsider.’ This seems like a good example of how people who take these questions seriously often think. Good questions are asked throughout, and there are good answers to essentially all of it, but those answers cannot be part of a book the length of IABIED, because not everyone has the same set of such questions.

Peter Thiel has called a number of people the antichrist, but his leading candidates are perhaps Greta Thunberg and Eliezer Yudkowsky. Very different of course.

weber: two sides of the same coin

Yep. As always, both paths get easier, so which way, modern AI user?

Xiao Ma: This should be in the museum of chart crimes.

There are so many more exhibits we need to add. Send her your suggestions.

I love a good chef’s kiss bad take.

Benjamin Todd: These are the takes.

Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh: Some “experts” claim that a single bipedal primate species designed all these wildly different modes of transport. The ridiculousness of this claim neatly illustrated the ridiculousness of the “AGI believers”.

Discussion about this post

AI #138 Part 2: Watch Out For Documents Read More »