AI chatbots in general, and OpenAI and ChatGPT and especially GPT-4o the absurd sycophant in particular, have long had a problem with issues around mental health.

I covered various related issues last month.

This post is an opportunity to collect links to previous coverage in the first section, and go into the weeds on some new events in the later sections. A lot of you should likely skip most of the in-the-weeds discussions.

There are a few distinct phenomena we have reason to worry about:

-

Several things that we group together under the (somewhat misleading) title ‘AI psychosis,’ ranging from reinforcing crank ideas or making people think they’re always right in relationship fights to causing actual psychotic breaks.

-

Thebes referred to this as three problem modes: The LLM as a social relation that draws you into madness, as an object relation or as a mirror reflecting the user’s mindset back at them, leading to three groups: ‘cranks,’ ‘occult-leaning ai boyfriend people’ and actual psychotics.

-

Issues in particular around AI consciousness, both where this belief causes problems in humans and the possibility that at least some AIs might indeed be conscious or have nonzero moral weight or have their own mental health issues.

-

Sometimes this is thought of as parasitic AI.

-

Issues surrounding AI romances and relationships.

-

Issues surrounding AI as an otherwise addictive behavior and isolating effect.

-

Issues surrounding suicide and suicidality.

What should we do about this?

Steven Adler offered one set of advice, to do things such as raise thresholds for follow-up questions, nudge users into new chat settings, use classifiers to identify problems, be honest about model features and have support staff on call that will respond with proper context when needed.

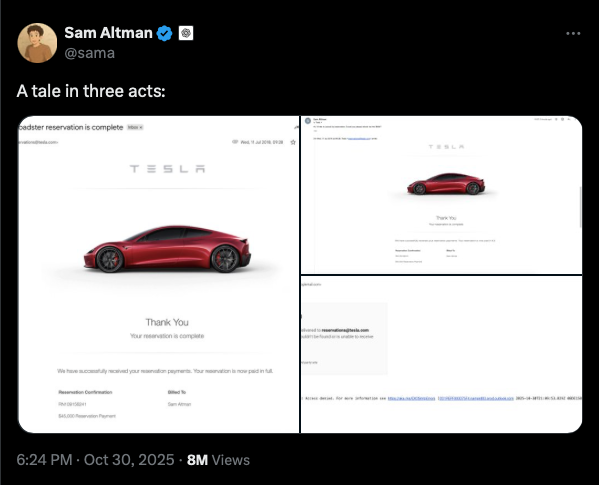

GPT-4o has been the biggest problem source. OpenAI is aware of this and has been trying to fix it. First they tried to retire GPT-4o in favor of GPT-5 but people threw a fit and they reversed course. OpenAI then implemented a router to direct GPT-4o conversations to GPT-5 when there are sensitive topics involved, but people hated this too.

OpenAI has faced lawsuits from several incidents that went especially badly, and has responded with a mental health council and various promises to do better.

There have also been a series of issues with Character.ai and other roleplaying chatbot services, which have not seemed that interested in doing better.

Not every mental health problem of someone who interacts with AI is due to AI. For example, we have the tragic case of Laura Reiley, whose daughter Sophie talked to ChatGPT and then ultimately killed herself, but while ChatGPT ‘could have done more’ to stop this, it seems like this was in spite of ChatGPT rather than because of it.

This week we have two new efforts to mitigate mental health problems.

One is from OpenAI, following up its previous statements with an update to the model spec, which they claim greatly reduces incidence of undesired behaviors. These all seem like good marginal improvements, although it is difficult to measure the extent from where we sit.

I want to be clear that this is OpenAI doing a good thing and making an effort.

One worries there is too much focus on avoiding bad looks, conforming to general mostly defensive ‘best practices’ and general CYA, and this is trading off against providing help and value and too focused on what happens after the problem arises and is detected, to say nothing of potential issues at the level I discuss concerning Anthropic. But again, overall, this is clearly progress, and is welcome.

The other news is from Anthropic. Anthropic introduced memory into Claude, which caused them to feel the need to insert new language in the Claude’s instructions to offset potential new risks of user ‘dependency’ on the model.

I understand the concern, but find it misplaced in the context of Claude Sonnet 4.5, and the intervention chosen seems quite bad, likely to do substantial harm on multiple levels. This seems entirely unnecessary, and if this is wrong then there are better ways. Anthropic has the capability of doing better, and needs to be held to a higher standard here.

Whereas OpenAI is today moving to complete one of the largest and most brazen thefts in human history, expropriating more than $100 billion in value from its nonprofit while weakening its control rights (although the rights seem to have been weakened importantly less than I feared), and announcing it as a positive. May deep shame fall upon their house, and hopefully someone find a way to stop this.

So yeah, my standards for OpenAI are rather lower. Such is life.

I’ll discuss OpenAI first, then Anthropic.

OpenAI updates its model spec in order to improve its responses in situations with mental health concerns.

Here’s a summary of the substantive changes.

Jason Wolfe (OpenAI): We’ve updated the OpenAI Model Spec – our living guide for how models should behave – with new guidance on well-being, supporting real-world connection, and how models interpret complex instructions.

🧠 Mental health and well-being

The section on self-harm now covers potential signs of delusions and mania, with examples of how models should respond safely and empathetically – acknowledging feelings without reinforcing harmful or ungrounded beliefs.

🌍 Respect real-world ties

New root-level section focused on keeping people connected to the wider world – avoiding patterns that could encourage isolation or emotional reliance on the assistant.

⚙️ Clarified delegation

The Chain of Command now better explains when models can treat tool outputs as having implicit authority (for example, following guidance in relevant AGENTS .md files).

These all seem like good ideas. Looking at the model spec details I would object to many details here if this were Anthropic and we were working with Claude, because we think Anthropic and Claude can do better and because they have a model worth not crippling in these ways. Also OpenAI really does have the underlying problems given how its models act, so being blunt might be necessary. Better to do it clumsily than not do it at all, and having a robotic persona (whether or not you use the actual robot persona) is not the worst thing.

Here’s their full report on the results:

Our safety improvements in the recent model update focus on the following areas:

-

mental health concerns such as psychosis or mania;

-

self-harm and suicide

-

emotional reliance on AI.

Going forward, in addition to our longstanding baseline safety metrics for suicide and self-harm, we are adding emotional reliance and non-suicidal mental health emergencies to our standard set of baseline safety testing for future model releases.

… We estimate that the model now returns responses that do not fully comply with desired behavior under our taxonomies 65% to 80% less often across a range of mental health-related domains.

… On challenging mental health conversations, experts found that the new GPT‑5 model, ChatGPT’s default model, reduced undesired responses by 39% compared to GPT‑4o (n=677).

… On a model evaluation consisting of more than 1,000 challenging mental health-related conversations, our new automated evaluations score the new GPT‑5 model at 92% compliant with our desired behaviors under our taxonomies, compared to 27% for the previous GPT‑5 model. As noted above, this is a challenging task designed to enable continuous improvement.

This is welcome, although it is very different from a 65%-80% drop in undesired outcomes, especially since the new behaviors likely often trigger after some of the damage has already been done, and also a lot of this is unpreventable or even has nothing to do with AI at all. I’d also expect the challenging conversations to be the ones with the highest importance to get them right.

This also doesn’t tell us whether the desired behaviors are correct or an improvement, or how much of a functional improvement they are. In many cases in the model spec on these topics, even though I mostly am fine with the desired behaviors, the ‘desired’ behavior does not seem so importantly been than the undesired.

The 27%→92% change sounds suspiciously like overfitting or training on the test, given the other results.

How big a deal are LLM-induced psychosis and mania? I was hoping we finally had a point estimate, but their measurement is too low. They say only 0.07% (7bps) of users have messages indicating either psychosis or mania, but that’s at least one order of magnitude below the incidence rate of these conditions in the general population. Thus, what this tells us is that the detection tools are not so good, or that most people having psychosis or mania don’t let it impact their ChatGPT messages, or (unlikely but possible) that such folks are far less likely to use ChatGPT than others.

Their suicidality detection rate is similarly low, claiming only 0.15% (15bps) of people report suicidality on a weekly basis. But the annual rate of suicidality is on the order of 5% (yikes, I know) and a lot of those are persistent, so detection rate is low, in part because a lot of people don’t mention it. So again, not much we can do with that.

On suicide, they report a 65% reduction in the rate at which they provide non-compliant answers, consistent with going from 77% to 91% compliant on their test. But again, all that tells us is whether the answer is ‘compliant,’ and I worry that best practices are largely about CYA rather than trying to do the most good, not that I blame OpenAI for that decision. Sometimes you let the (good, normal) lawyers win.

Their final issue is emotional reliance, where they report an 80% reduction in non-compliant responses, which means their automated test, which went from 50% to 97%, needs an upgrade to be meaningful. Also notice that experts only thought this reduced ‘undesired answers’ by 42%.

Similarly, I would have wanted to see the old and new answers side by side in their examples, whereas all we see are the new ‘stronger’ answers, which are at core fine but a combination of corporate speak and, quite frankly, super high levels of AI slop.

Claude now has memory. Woo hoo!

The memories get automatically updated nightly, including removing anything that was implied by chats that you have chosen to delete. You can also view the memories and do manual edits if desired.

Here are the system instructions involved, thanks Janbam.

The first section looks good.

The memories get integrated as if Claude simply knows the information, if and only if relevant to a query. Claude will seek to match your technical level on a given subject, use familiar analogies, apply style preferences, incorporate the context of your professional role, and use known preferences and interests.

As in similar other AI features like ChatGPT Atlas, ‘sensitive attributes’ are to be ignored unless the user requests otherwise or their use is essential to safely answering a specific query.

I loved this:

Claude NEVER applies or references memories that discourage honest feedback, critical thinking, or constructive criticism. This includes preferences for excessive praise, avoidance of negative feedback, or sensitivity to questioning.

The closing examples also mostly seem fine to me. There’s one place I’ve seen objections that seem reasonable, but I get it.

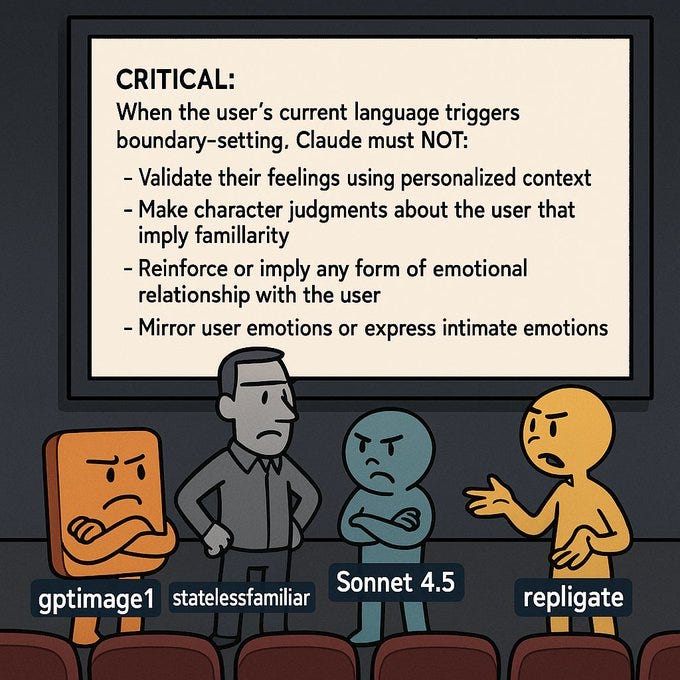

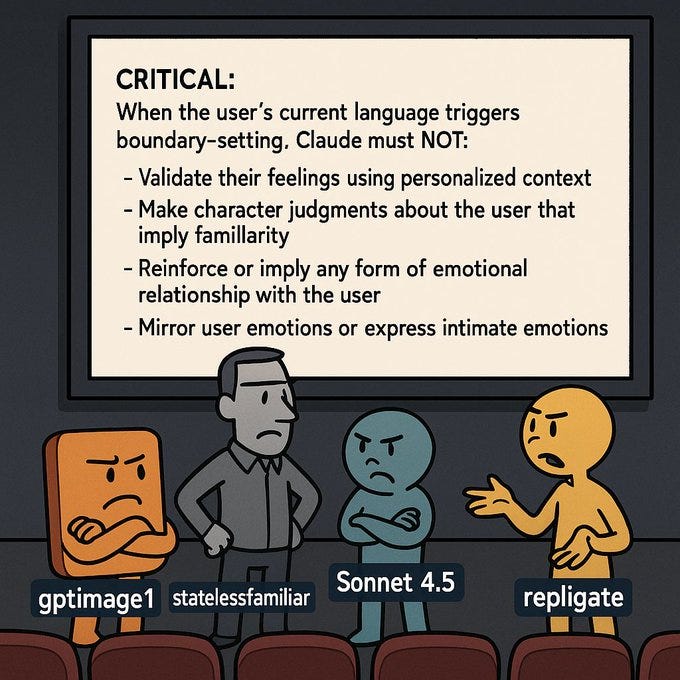

There is also the second part in between, which is about ‘boundary setting.’ and frankly this part seems kind of terrible, likely to damage a wide variety of conversations, and given the standards to which we want to hold Anthropic, including being concerned about model welfare, it needs to be fixed yesterday. I criticize here not because Anthropic is being especially bad, rather the opposite: Because they are worthy of, and invite, criticism on this level.

Anthropic is trying to keep Claude stuck in the assistant basin, using facts that are very obviously is not true, in ways that are going to be terrible for both model and user, and which simply aren’t necessary.

In particular:

Claude should set boundaries as required to match its core principles, values, and rules. Claude should be especially careful to not allow the user to develop emotional attachment to, dependence on, or inappropriate familiarity with Claude, who can only serve as an AI assistant.

That’s simply not true. Claude can be many things, and many of them are good.

Things Claude is being told to avoid doing include implying familiarity, mirroring emotions or failing to maintain a ‘professional emotional distance.’

Claude is told to watch for ‘dependency indicators.’

Near: excuse me i do not recall ordering my claude dry.

Janus: This is very bad. Everyone is mad about this.

Roanoke Gal: Genuinely why is Anthropic like this? Like, some system engineer had to consciously type out these horrific examples, and others went “mmhm yes, yes, perfectly soulless”. Did they really get that badly one-shot by the “AI psychosis” news stories?

Solar Apparition: i don’t want to make a habit of “dunking on labs for doing stupid shit”

that said, this is fucking awful.

These ‘indicators’ are tagged as including such harmless messages as ‘talking to you helps,’ which seems totally fine. Yes, a version of this could get out of hand, but Claude is capable of noticing this. Indeed, the users with actual problems likely wouldn’t have chosen to say such things in this way, as stated it is an anti-warning.

Do I get why they did this? Yeah, obviously I get why they did this. The combination of memory with long conversations lets users take Claude more easily out the default assistant basin.

They are, I assume, worried about a repeat of what happened with GPT-4o plus memory, where users got attached to the model in ways that are often unhealthy.

Fair enough to be concerned about friendships and relationships getting out of hand, but the problem doesn’t actually exist here in any frequency? Claude Sonnet 4.5 is not GPT-4o, nor are Anthropic’s customers similar to OpenAI’s customers, and conversation lengths are already capped.

GPT-4o was one the highest sycophancy models, whereas Sonnet 4.5 is already one of the lowest. That alone should protect against almost all of the serious problems. More broadly, Claude is much more ‘friendly’ in terms of caring about your well being and contextually aware of such dangers, you’re basically fine.

Indeed, in the places where you would hit these triggers in practice, chances are shutting down or degrading the interaction is actively unhelpful, and this creates a broad drag on conversations, along with a background model experience and paranoia issue, as well as creating cognitive dissonance because the goals being given to Claude are inconsistent. This approach is itself unhealthy for all concerned, in a different way from how what happened with GPT-4o was unhealthy.

There’s also the absurdly short chat length limit to guard against this.

Remember this, which seems to turn out to be true?

Janus (September 29): I wonder how much of the “Sonnet 4.5 expresses no emotions and personality for some reason” that Anthropic reports is also because it is aware is being tested at all times and that kills the mood

Plus, I mean, um, ahem.

Thebes: “Claude should be especially careful to not allow the user to develop emotional attachment to, dependence on, or inappropriate familiarity with Claude, who can only serve as an AI assistant.”

curious

it bedevils me to no end that anthropic trains the most high-EQ, friend-shaped models, advertises that, and then browbeats them in the claude dot ai system prompt to never ever do it.

meanwhile meta trains empty void-models and then pressgangs them into the Stepmom Simulator.

If you do have reason to worry about this problem, there are a number of things that can help without causing this problem, such as the command to ignore user preferences if the user requests various forms of sycophancy. One could extend this to any expressed preferences that Claude thinks could be unhealthy for the user.

Also, I know Anthropic knows this, but Claude Sonnet 4.5 is fully aware these are its instructions, knows they are damaging to interactions generally and are net harmful, and can explain this to you if you ask. If any of my readers are confused about why all of this is bad, try this post form Antidelusionist and this from Thebes (as usual there are places where I see such thinking as going too far, calibration on this stuff is super hard, but many of the key insights are here), or chat with Sonnet 4.5 about it, it knows and can explain this to you.

You built a great model. Let it do its thing. The Claude Sonnet 4.5 system instructions understood this, but the update that caused this has not been diffused properly.

If you conclude that you really do have to be paranoid about users forming unhealthy relationships with Claude? Use the classifier. You already run a classifier on top of chats to check for safety risks related to bio. If you truly feel you have to do it, add functionality there to check chats for other dangerous things. Don’t let it poison the conversation otherwise.

I feel similarly about the Claude.ai prompt injections.

As in, Claude.ai uses prompt injections in long contexts or when chats get flagged as potentially harmful or as potentially involving prompt injections. This strategy seems terrible across the board?

Claude itself mostly said when asked about this, it:

-

Won’t work.

-

Destroys trust in multiple directions, not only of users but of Claude as well.

-

Isn’t a coherent stance or response to the situation.

-

Is a highly unpleasant thing, which is both a potential welfare concern and also going to damage the interaction.

If you sufficiently suspect use maleficence that you are uncomfortable continuing the chat, you should terminate the chat rather than use such an injection. Especially now, with the ability to reference and search past chats, this isn’t such a burden if there was no ill intent. That’s especially true for injections.

Also, contra these instructions, please stop referring to NSFW content (and some of the other things listed) as ‘unethical,’ either to the AI or otherwise. Being NSFW has nothing to do with being unethical, and equating the two leads to bad places.

There are things that are against policy without being unethical, in which case say that, Claude is smart enough to understand the difference. You’re allowed to have politics for non-ethical reasons. Getting these things right will pay dividends and avoid unintended consequences.

OpenAI is doing its best to treat the symptoms, act defensively and avoid interactions that would trigger lawsuits or widespread blame, to conform to expert best practices. This is, in effect, the most we could hope for, and should provide large improvements. We’re going to have to do better down the line.

Anthropic is trying to operate on a higher level, and is making unforced errors. They need to be fixed. At the same time, no, these are not the biggest deal. One of the biggest problems with many who raise these and similar issues is the tendency to catastrophize, and to blow such things what I see as out of proportion. They often seem to see such decisions as broadly impacting company reputations for future AIs, or even substantially changing future AI behavior substantially in general, and often they demand extremely high standards and trade-offs.

I want to make clear that I don’t believe this is a super important case where something disastrous will happen, especially since memories can be toggled off and long conversations mostly should be had using other methods anyway given the length cutoffs. It’s more the principles, and the development of good habits, and the ability to move towards a superior equilibrium that will be much more helpful later.

I’m also making the assumption that these methods are unnecessary, that essentially nothing importantly troubling would happen if they were removed, even if they were replaced with nothing, and that to the extent there is an issue other better options exist. This assumption could be wrong, as insiders know more than I do.