No, NASA hasn’t found life on Mars yet, but the latest discovery is intriguing

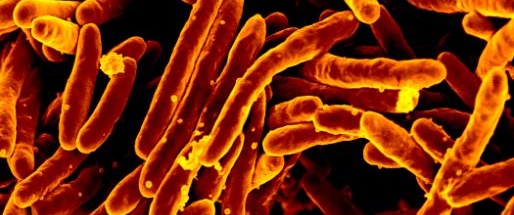

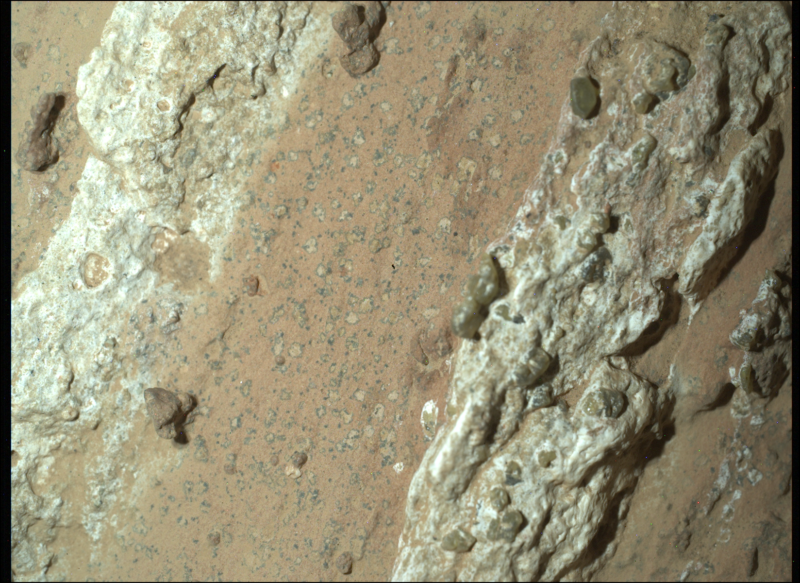

Enlarge / NASA’s Perseverance rover discovered “leopard spots” on a reddish rock nicknamed “Cheyava Falls” in Mars’ Jezero Crater in July 2024.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

NASA’s Perseverance rover has found a very intriguing rock on the surface of Mars.

An arrowhead-shaped rock observed by the rover has chemical signatures and structures that could have been formed by ancient microbial life. To be absolutely clear, this is not irrefutable evidence of past life on Mars, when the red planet was more amenable to water-based life billions of years ago. But discovering these colored spots on this rock is darn intriguing and has Mars scientists bubbling with excitement.

“These spots are a big surprise,” said David Flannery, an astrobiologist and member of the Perseverance science team from the Queensland University of Technology in Australia, in a NASA news release. “On Earth, these types of features in rocks are often associated with the fossilized record of microbes living in the subsurface.”

What the rover found

This is a very recent discovery, and the science has not yet been peer-reviewed. The sample was collected on July 21—a mere four days ago—as the rover explored the Neretva Vallis riverbed. This valley was formed long ago when water rushed into Jezero Crater.

The science team operating Perseverance has nicknamed the rock Chevaya Falls and subjected it to multiple scans by the rover’s SHERLOC (Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman & Luminescence for Organics & Chemicals) instrument. The distinctive colorful spots, containing both iron and phosphate, are a smoking gun for certain chemical reactions—rather than microbial life itself.

On Earth, microbial life can derive energy from these kinds of chemical reactions. So, what we have here is a plausible source of energy for microbes on Mars. In addition, there are organic chemicals present on the same rock, which is consistent with something living there. From this, it is tempting to jump to the idea of microbes living on a rock, eons ago, in a Martian river. But this is not direct evidence of life.

NASA has a seven-step process for determining whether something can be confirmed as extraterrestrial life. This is known as the CoLD scale, for Confidence of Life Detection. In this case, the detection of these spots on a Martian rock represents just the first of seven steps—for example, scientists must still rule out non-biological possibility and identify other signals to have confidence in off-world life.

Bring them home

According to NASA, Perseverance has used all of its available instrumentation to study Chevaya Falls. “We have zapped that rock with lasers and X-rays and imaged it literally day and night from just about every angle imaginable,” said Ken Farley, Perseverance project scientist. “Scientifically, Perseverance has nothing more to give.”

The discovery provides some wind in the sails for NASA’s flagging efforts to devise and fly a Mars Sample Return mission. The agency’s most recent plan, costing $11 billion, was determined to be too expensive. Now, the space agency is asking the industry for help. In June it commissioned 10 studies on alternative means of returning rocks from Mars sooner, and presumably for a lower cost.

Now, scientists can point to rocks like Chevaya Falls and say this is precisely why they must be studied in ultra-capable labs back on Earth.

No, NASA hasn’t found life on Mars yet, but the latest discovery is intriguing Read More »