-

College Applications.

-

The College Application Essay (Is) From Hell.

-

Don’t Guess The Teacher’s Password, Ask For It Explicitly.

-

A Dime a Dozen.

-

Treat Admissions Essays Like Games of Balderdash.

-

It’s About To Get Worse.

-

Alternative Systems Need Good Design.

-

The SAT Scale Is Broken On Purpose.

In case you missed it, yes, of course Harvard admissions are way up and Harvard did this on purpose. The new finding is that Harvard was recruiting African American applicants in particular, partly in order to balance conditional acceptance rates. One could of course also argue that the goal was ‘to find more worthy students,’ with the counterevidence being that the test scores of such applicants declined as more applications came in (as they obviously would for any group) but the scores of those who got admitted didn’t change.

As a student, one needs to understand that schools love applications they can then reject, and might care about that even more depending on your details. So when they tell you to apply, that you have a shot, that is not the evidence you want it to be.

Or, your future depends on knowing exactly the right way to lie your ass off, and having sufficiently low integrity to do so shamelessly.

One can ask questions like: If you can get hired by Google for an engineering job, you have a 4.4 GPA and a 1590 SAT score, and you get rejected by 5 University of California schools and 16 out of 18 schools overall, is it fair to say that was probably an illegal form of racial discrimination, as his lawsuit is claiming? It doesn’t automatically have to be that, there could in theory be other details of his application that are problems.

I’d like to say to that objection ‘who are we kidding’ but maybe? You had two groups debating this recently, after a different applicant, Zack Yadegari, got rejected from all the colleges for being too successful and daring to write about that.

One group said this was the situation, And That’s Terrible.

The other group said, yes this is the situation, And You’re Terrible, get with the program or go off and die, oh and it’s just the essay, he can apply next year it’s fine.

Zack Yadegari: 18 years old

34 ACT

4.0 GPA

$30M ARR biz

Stanford ❌ MIT ❌ Harvard ❌ Yale ❌ WashU ❌ Columbia ❌ UPenn ❌ Princeton ❌ Duke ❌ USC ❌ Georgia Tech ✅ UVA ❌ NYU ❌ UT ✅ Vanderbilt ❌ Brown ❌ UMiami ✅ Cornell ❌

I dedicated 2 straight weeks to my essays doing nothing else. Had them looked over by the best writers I know.

Michael Druggan: When I applied to Harvard, I was a USAMO winner (only 12 per year and with significant duplicates that works out to significantly less than 12 per graduating class). I also had a clean 36 in every section on the ACT from my very first attempt. Neither of those are dime-a-dozen stats.

The admissions committee didn’t care. They rejected me in favor of legions of clearly academically inferior candidates who did a better job kissing their asses in their application essays. Let’s not pretend this process is anything but a farce.

Avi Shiffmann: My (in my opinion awful) personal statement that got me into Harvard. [comments mostly talk about how the essay is good actually]

Felpix: College admissions is so competitive, kids are just crashing out [describes a kid who basically did everything you could imagine to get in to study Computer Science, and still got rejected from the majors, reasons unknown.]

Gabriel: this is incredibly sad, someone spent their entire childhood to get into MIT with perfect scores without getting in, and now can’t live his dream

all this effort could have been spent on becoming economically valuable and he’d now have his dream job. this is obviously not this persons fault, but the fault of collective inability to change, and constantly reaffirming our beliefs that whatever we have now is working great. we put this talented person into doing fake work to get the chance to do more fake work, to get a degree, which is seen as much more important than the actual work being performed later

he wasted his entire childhood, literally irreparable damage

The kid Felpix is quoting is going to have a fine future without academia, and yes they’d be a year ahead of the game if they’d spent all that time learning to code better instead of playing the college game. It’s not even clear they should have been trying to go to college at all, other than VCs wanting to see you go for a bit and then drop out.

Zack’s mistake was, presumably, asking the best writers he knew rather than people who know to write college essays in particular.

Dr. Ellie Murray, ScD: The fact that every academic reads this guy’s essay and is like, yeah of course you didn’t get in, but tech twitter all seem to think he was a shoe-in and cheated out of a spot… We’re living in 2 different worlds and it’s a problem.

If you’re writing your own college apps & want to know how to avoid these pitfalls, there are lots of great threads about this guy’s essay. Start here.

Mason: The essay is easily the most regressive and gameable part of the app. The point tech twitter is making is not that the essay is good, but that if this kid came from the “right” family his essay would have been ghostwritten by an admissions coach anyway

Amal Dorai: It’s supposed to be gameable! They’re trying to put their imprimatur on a meritocratic class that can “game” its way into the country’s power elite. Yes it’s a sort of pre-Trumpian way of thinking but they are not just looking for the country’s future NVIDIA engineers.

Monica Marks: Statistically well-qualified applicants come a dime a dozen in elite admissions, more than most people realise.

For every student w/ perfect scores like Zach, there’s a student w/ near perfect scores & more humility who’s overcome terrible circumstances & does not seem entitled.

[she gives advice on how to write a good essay, basically ‘sell that you can pretend that you need this in order to fight some Good Fight that liberals love and are super motivated and shows the proper appreciation and humility etc, and in his case he should have emphasized his Forbes essay rather than his actual achievements.’]

Wind Come Calling: I’ve read applications from kids like this and, being obviously very bright, they tend to think they can hide their arrogance or sense of entitlement, that it won’t come through in their application or that the reviewers will miss it. they are mistaken.

Lastdance: “You must follow my lead and feign humility. If you are merely gifted then go somewhere else, it’s the gifted liar we want!”

Kelsey Piper: before you make fun of someone’s college application personal statement, I urge you to go way back into your old emails and read your own college application essays, I promise this will cure you of the urge to say anything mean about anyone else’s

Tracing Woodgrains: I’m seeing people criticize this personal statement, and—look. Don’t subject yourself to the indignity of defending arbitrary games. the Personal Statement is the lowest genre of essay and the worst admissions practice. his resumé speaks for itself.

“but the personal statement is…”

…an arbitrary game of “guess what’s in my head,” inauthenticity embodied by writers and readers alike. an undignified hazing ritual whether written by you, your $200/hr advisor, or your good friend Claude.

good? bad? junk either way.

every time people defend this system on its own terms it makes me grimace

do not validate a system that encourages kids to twist themselves into pretzels and then purports to judge their whole persons

the whole game is socially corrosive.

so like [Monica Marks from above] seems perfectly nice but I simply do not want access to be gatekept by “did I strike the perfect tone to flatter her sensibilities”

the red flags – someone go tell UMass Amherst they got a dud! or don’t, bc it’s a deranged process

Tracing Woods (also): It’s not the competition that gets people, I suspect, but the arbitrariness. Young, ambitious people jump through a million hoops to roll the dice. It is unhealthy to let this process control so much of the collective youth psyche. Elite college admissions are twisted.

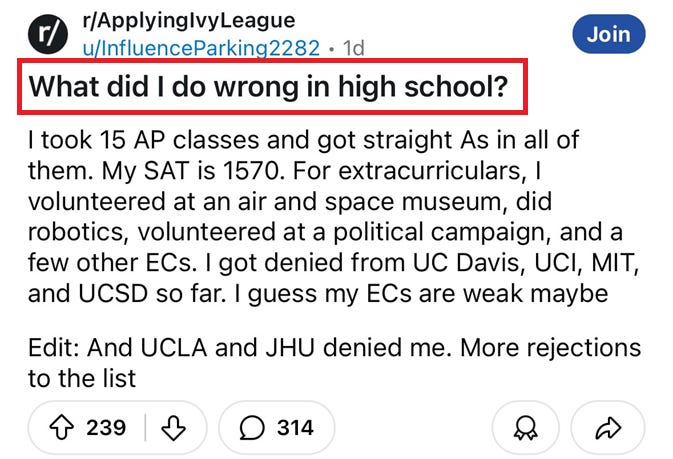

Deedy: Reddit father says son who is

— #1/476 in high school

— 1580/1600 on SAT

— 5/5 on 18 APs

got rejected by all the Ivies for CS. Only got UMass Amherst.

It’s college season and this is the #1 post last week on r/ApplyingToCollege.

Competition is fine, but this just feels unfair.

Of course, some people will say it’s fake but if you read the OP’s comments it feels real. Son is 1/4th Korean 3/4th white, according to his comments.

Depending on where you set the bar for applicants, ‘statistically well-qualified’ might be ‘dime a dozen,’ maybe even being #1 in your HS with 1580 SAT and 18 5/5 APs is ‘a dime a dozen.’ That’s by design, as I discuss elsewhere, the tests cap out on purpose. If the top colleges wanted differentiation the tests would provide it.

But you know what very much is not ‘a dime a dozen’? Things like being a USAMO winner or founding a $30mm ARR business.

If admissions chooses not to care much about even that, and merely puts it into the ‘statistical qualification’ bucket and mostly looks to see who within that bucket is better at playing the Guess the Teacher’s Password game and playing their PTCs (Personal Trauma Cards) and being members of the preferred groups and so on, well, it is what it is.

If you see someone thinking being a USAMO winner and founding a $30mm ARR business means they shouldn’t be feigning false humility, and think ‘that’s an asshole,’ well, I have a humble suggestion about who the asshole is in this situation.

And it’s totally fair to point out that this is indeed what it is, and that our academic system checks your ‘statistical qualifications’ but is mostly actively selecting for this form of strategic dishonesty combined with class performance and some inherent characteristics.

That is very different from saying that this is good, actually. It’s not good.

I would also however say that it is now common knowledge that this is how it works. So, given that it is common knowledge how this works, while I place a super high value on honesty and honor, I hereby give everyone reading this full ethical and moral permission to completely lie your ass off.

College admission essays are not a place where words have meaning and you are representing your statement as true. So aside from specific verifiable things like your GPA or SAT score, you can and should lie your ass off the same way you would lie when playing a game of Diplomacy or Balderdash. It doesn’t count, and I will not hold it against you, at all.

Oh, also, requiring all these hours of volunteer work is straight up enslavement of our kids for child labor, and not the good kind where you learn valuable skills.

Those disputes were at the top of the scale. An at least somewhat reasonable response would be ‘boo hoo, you didn’t get into the top 25 colleges in the country, go to your state college and you’ll be fine.’

Except that the state colleges are sometimes doing it too. And that’s not okay, at all.

Analytic Valley Girl Chris: State universities should be legally mandated to accept any in state graduate who meets certain academic thresholds, save some compelling disqualification. Generic “not what we’re looking for” shouldn’t be allowed.

As in, MIT can do what it wants, it’s their loss, but UC San Diego and UC Davis?

Yes, obviously if you simply want ‘any college at all’ there will always be options for such students, but that degree and experience, and the connections available to be made, will offer dramatically lower value. Going is probably a large mistake.

The ‘top X% of your class’ system is excellent, such as Texas’s top 10% rule. I’d supplement that with a points system or threshold rules or both for grades, test scores and other quantifiable achievements, with a known minimum auto-admission threshold.

UATX does a simplified version of this, the deadline for this year has passed.

University of Austin (AUTX): College admissions are unjust.

Not just biased. Not just broken. Unjust.

Students spend high school anxiously stacking their résumés with hollow activities, then collect generic recommendation letters and outsource their essays to tutors or AI. Admissions at elite colleges now come down to who you know, your identity group, or how well you play the game.

This system rewards manipulation, not merit. It selects for conformity, not character.

That’s why we’re introducing the University of Austin’s new admissions policy:

If you score 1460+ on the SAT, 33+ on the ACT, or 105+ on the CLT, you will be automatically admitted, pending basic eligibility and an integrity check. Below that threshold, you’ll be evaluated on your test scores, AP/IB results, and three verifiable achievements, each described in a single sentence.

That’s it.

We care about two things: Intelligence and courage.

Intelligence to succeed in a rigorous intellectual environment (we don’t inflate grades). Courage to join the first ranks of our truth-oriented university.

College admission should be earned—not inherited, bought, or gamed. At UATX, your merit earns you a place—and full tuition scholarship.

Apply here by April 15.

Note the deadline. Because your decisions are deterministic, you get to move last.

As in, all they get to sweep up all these students whose essays were rejected or got discriminated against. Then we get to find out what happens when you put them all together. And you get to see which employers are excited by that, and which aren’t.

The New York Times headline writers understood the assignment, although it’s even worse than this: Elite Colleges Have Found a New Virtue For Applicants To Fake.

The basic version is indeed a new virtue to fake, combined with a cultural code to crack and teacher’s password to guess, the ‘disagreement question’:

Alex Bronzini-Vender (Sophomore, Harvard University, hire him): This time I found a new question: “Tell us about a moment when you engaged in a difficult conversation or encountered someone with an opinion or perspective that was different from your own. How did you find common ground?”

It’s known as the disagreement question, and since the student encampments of spring 2024 and the American right’s attacks on universities, a growing number of elite colleges have added it to their applications.

This didn’t escalate quickly so much as skip straight to the equilibrium. Kids are pros.

The trouble is that the disagreement question — like much of the application process — isn’t built for honesty. Just as I once scrambled to demonstrate my fluency in D.E.I., students now scramble to script the ideal disagreement, one that manages to be intriguing without being dangerous.

So now there’s a new guessing game in town.

Then again, maybe demonstrating one’s ability to delicately navigate controversial topics is the point. Perhaps the trick is balance? Be humble; don’t make yourself look too right. But you can’t choose a time when you were entirely wrong, either. Or should you tailor your responses by geography, betting that, say, a Southern admissions officer would be more likely to appreciate a conservative-leaning anecdote?

The emerging consensus in the application-prep industry is that it’s best to avoid politics entirely. … Dr. Jager-Hyman, for her part, usually advises students to choose a topic that is meaningful to them but unlikely to stoke controversy — like a time someone told you your favorite extracurricular activity was a waste of time.

So far, ordinary terrible, sure, fine, I suppose it’s not different in kind than anything else in the college essay business. Then it gets worse.

This fall, an expanding number of top schools — including Columbia, M.I.T., Northwestern, Johns Hopkins, Vanderbilt and the University of Chicago — will begin accepting “dialogues” portfolios from Schoolhouse.world, a platform co-founded by Sal Khan, the founder of Khan Academy, to help students with math skills and SAT prep.

High-schoolers will log into a Zoom call with other students and a peer tutor, debate topics like immigration or Israel-Palestine, and rate one another on traits like empathy, curiosity or kindness. The Schoolhouse.world site offers a scorecard: The more sessions you attend, and the more that your fellow participants recognize your virtues, the better you do.

“I don’t think you can truly fake respect,” Mr. Khan said.

Even as intended this is terrible already:

Owl of Athena: Remember when I told you Sal Khan was evil? I didn’t know the half of it!

Meet the Civility Score, courtesy of Khan’s “Dialogues.”

Get your kids used to having a social credit score, and make sure they understand their highest value should be the opinion of their peers! What could possibly go wrong?!

Steve McGuire: Elite universities are going to start using peer-scored civility ratings for admissions?!

Sorry, that’s a terrible idea. Why not just admit people based on their scores and then teach them to debate and dialogue?

You don’t need to go full CCP to solve this problem.

Nate Silver: This is basically affirmative action for boring people.

Blightersort: it is kind of amazing that elite schools would look at the current world and worry they are not selecting for conformity strongly enough and then work on new ways to select for conformity

Except of course it is way worse than that on multiple levels.

Remember your George Burns: “Sincerity is the most important thing. If you can fake that you’ve got it made.”

Of course you can fake respect. I do it and see it all the time. It is a central life skill.

Also, if you’re not generally willing to or don’t know how to properly pander to peers in such settings, don’t ‘read the room’ or are ugly? No college for you.

You can, and people constantly do, fake empathy, curiosity and kindness. It is not only a central life skill, but it is considered a central virtue.

And the fortunate ones won’t have to do it alone: They’ll have online guides, school counselors and private tutors to help them learn to simulate earnestness.

You could argue that one cannot fake civility, because there is no difference between faked civility and real civility. It lives in the perception of the audience. And you can argue that to some extent this applies to other such virtues too.

Quite possibly, there will be rampant discrimination of other kinds, as well. Expect lots of identify-based appeals. The game will be won by those who play to win it.

And then let’s address the elephant in the room. Notice this sentence:

High-schoolers will log into a Zoom call with other students and a peer tutor, debate topics like immigration or Israel-Palestine, and rate one another on traits like empathy, curiosity or kindness.

Yeah. Um.

Neils Hoven: Oh look, they figured out how to scale ideological conformity testing.

Brain in a jar: Haha hot people and conformists will win. Fuck.

If you have a bunch of high schoolers rating each other on ‘empathy, curiosity or kindness’ on the basis of discussions of those topics, that is a politics test. If you go in there and take a right-wing stance on immigration? No college for you. Not pledging your support for ending the state of Israel? No college for you. Indeed, I’m willing to bet that going in with actual full empathy and curiosity will get you lower, not higher, scores than performative endorsement.

To be fair, the website doesn’t emphasize those topics in particular, although I’m assuming they were listed because the author here encountered them. Instead, it looks like this:

The problem will persist regardless, if less egregiously. Across essentially all topics, the peer consensus in high school is left-wing, and left-wing consensus holds that left-wing views are empathic and curious and kind, whereas anything opposed to them is not. I would very much not advice anyone oppose student debt ‘relief,’ meaning abrogation of contracts, or anything but the most radical positions on climate change, or oppose aggressive moderation and censorship of social media.

Short of using AI evaluators (an actually very good idea), I don’t see a way around the problem that this is not a civility test, it is a popularity and ideological purity challenge, and we are forcing everyone to put on an act.

On the positive side (I am not sure if I am kidding), it also is potentially a game theory challenge. 5 for 5, anyone? Presumably students will quickly learn the signals of how to make the very obvious deals with each other.

Also you see what else this is testing? You outright get a higher score for participating in more of these ‘dialogues.’ You also presumably learn, over time, the distribution of other participants, and what techniques work on them, and develop your ‘get them to rank you highly’ skills. So who wants to grind admissions chances between hours of assigned busywork (aka ‘homework’) and mandatory (‘community service’) shifts working as an indentured servant, perhaps at the homeless shelter?

You cannot simply do this:

Zaid Jilani: Make SAT and GPA almost all of the college admissions standard, any essays should be analytical like on GRE rather than personal.

Mike Riggs: And you have no concerns about grade inflation?

Zaid Jilani: I do but how is that any different than status quo? Have to deal with that issue regardless. FWIW that’s much worse in college than high school.

Kelsey Piper: yep. just cut all the holistic shit. it turns high school into hell without meaningfully identifying the kids most prepared to contribute at top schools let alone teaching them anything

Emmett Shear: Overfit! Overfit! You cannot make your model robust by adding more parameters, only more accurate in the moment! Trying to create a global rating for “best students” is a bad idea and intrinsically high-complexity. Stop doing that.

Most of the holistic stuff needs to go. The essay needs to either go fully, or become another test taken in person, ideally graded pass-fail, to check for competence.

You do need a way to control for both outstanding achievement in the field of excellence.

I would thus first reserve some number of slots for positive selection outside the system, for those who are just very obviously people you want to admit.

I also think you need to have a list of achievements, at least on AP and other advanced tests, that grant bonus points. The SAT does not get hard enough or cover a wide enough set of topics.

I think you mostly don’t need to worry about any but the most extreme deal breakers and negative selection. Stop policing anything that shouldn’t involve actual police.

The other problem then is that at this level of stakes everything will get gamed. You cannot use a fully or even incompletely uncontrolled GPA if you are not doing holistic adjustments. GPAs would average 4.33 so fast it would make your head spin. Any optional class not playing along would be dropped left and right. And so on. If you want to count GPA at all, you need to adjust for school and by-class averages, and adjust for the success rate of the school of origin as a function of average-adjusted GPA controlling for SAT, and so on.

The ultimate question here is whether you want students in high school to be maximizing GPA as a means to college admissions. It can be a powerful motivating factor, but it also warps motivation. My inclination is to say you want to use it mostly as a threshold effect, with the threshold rising as you move up the ladder, with only modest bonus points for going beyond that, or use it as a kind of fast-track that gets you around other requirements, ideally including admission fees.

Where it gets tricky is scholarships. Even if admission depends only on SAT+AP and similar scores plus some extraordinary achievements and threshold checks, the sticker prices of colleges are absurd. So if scholarships depend on other triggers, you end up with the same problem, or you end up with a two-tier system where those who need merit scholarships have to game everything, probably with the ‘immune tier’ rather small since even if you can afford full price that doesn’t mean you want to pay it.

Sahsa Gusev has a fun thread pointing out various flaws that lead one back to a holistic approach rather than an SAT+GPA approach. I think that if you do advanced stats on the GPA (perhaps create GPV, grade percentile value, or GVOA, or grade value over average), and add in advanced additional objective examinations as sources of additional points, perhaps including a standardized entrance exam at most, and have a clearly defined list of negative selection dealbreakers (that are either outright dealbreakers or not, nothing in between), you can get good enough that letting students mostly game that is better than the holistic nightmare, and you can two-track as discussed above by reserve some slots for the best of the best on pure holistic judgment.

It’s not perfect, but no options are perfect, and I think these are the better mistakes.

Another way of putting this is:

Sasha Gusev: *Open: Office of the president at the new 100% Meritocratic University*

President: We’ve admitted the top 2,000 applicants by GPA and SATs. How are they doing?

Admissions: Several hundred valedictorians who’ve never gotten a B in their life are now at the bottom of all their classes and are experiencing a collective mental breakdown. Also our sports teams are an embarrassment.

[Zvi’s alternative continuation]: President: Okay. Is there a problem?

Admissions: Yes, this is scaring off some potential applicants, and also our sports teams are an embarrassment.

President: If a few get scared off or decide to transfer to feel smarter because they care mainly about signaling and positional goods rather than learning, that seems fine, make sure our office helps them get good placements elsewhere. And yeah, okay, or sports teams suck, but remind me why I should care about that?

Admissions: Because some students won’t want to go to a school whose sports teams suck and alumni won’t give us money that way.

President: Fine, those students can go elsewhere, too, it’s not like we’re going to be short on applicants, and that’s why we charge tuition.

Admissions: But if all we do is math then you’re going to replace me with an AI!

President: Well, yes.

[End scene.]

Paul Graham: Part of the problem with college admissions is that the SAT is too easy. It doesn’t offer enough resolution at the high end of the scale, and thus gives admissions officers too much discretion.

The problem is that we have tests that solve this problem but no one cares that much about them. Once you are maximizing the SAT, the attitude is not ‘well then, okay, let’s give them the LSAT or GRE and see how many APs they can ace,’ it’s ‘okay we’ll give them a tiny boost for each additional AP and such but mostly we don’t care.’ If the SAT bell curve went up to 2000, then they’d be forced to care, and differentiate 1570 from 1970.

That doesn’t seem hard to do? All you have to do is add some harder questions?

Or alternatively, you could have the ASAT (Advanced SAT), which is the same test on the same curve (a 1500 on ASAT is a 1500 on the SAT), except it’s harder, if you don’t earn at least 1400 you get back a null result the way you do on the USAMO or Putnam, and it goes up to 2500, and you can choose to take that instead. Yes, that’s not technically so different from what we do already, but it would feel very different – you’d be looking at that 1950 in that spot and it would be a lot harder to ignore.

Yeah, well, on that front it just got even worse, and the ACT is making similar changes:

Steve McGuire: Reading passages on the SAT have been shortened from 500-750 words down to 25-150. They say “the eliminated reading passages are ‘not an essential prerequisite for college’ and that the new, shorter content helps ‘students who might have struggled to connect with the subject matter.’” The reality, of course, is that the test is getting easier because so many students are struggling.

Zac Hill: This is capital-B bad not just for the obvious reason (reading is Good) but for the maybe-more-important second-order reason that this is not just about reading; it’s about all information synthesis involving the construction of models as a product of sustained attention.

Alex Tabarrok: SOD: “The SAT now caters to students who have trouble reading long, complex texts.”

Meanwhile in the math section, students have more time per question and free use of a calculator, without the questions changing.

On top of that, this paper says the Math SAT declined in rigor by 71 points between 2008 and 2023, which would mean that we have a 107-point decline in average performance that cuts across major demographic groups. Yikes, but also comments point out that the decline is largely caused by more students taking the test, which should indeed cause them to lower the grading curve. Relative score is what matters, except that we’re running into a lot more cases where 800 isn’t getting the job done.

Schools could of course move to the Classic Learning Test (CLT) or others that would differentiate between students. Instead, they are the customers of the ACT and SAT, and the customer is always right.

The only way to interpret this is that the colleges want to differentiate student ability up to some low minimum threshold, because otherwise the students fail out, but they actively do not want to differentiate on ability at the high end. They prefer other criteria. I will not further speculate as to why.

Perhaps even more important than all that is this, it cannot be overstated how much I see this screwing almost everyone and everything up:

Nephew Jonathan (QTing Tracing Woods above): I’m gonna hijack this: if there’s one thing that explains why everyone under the age of 40 seems to be a nervous wreck it’s the reduction of life to “guessing the teacher’s password” for everything.

Dating apps? Guess the girl’s password. College admissions? Grad school? HR personality screenings?