Lead poisoning has been a feature of our evolution

A recent study found lead in teeth from 2 million-year-old hominin fossils.

Our hominid ancestors faced a Pleistocene world full of dangers—and apparently one of those dangers was lead poisoning.

Lead exposure sounds like a modern problem, at least if you define “modern” the way a paleoanthropologist might: a time that started a few thousand years ago with ancient Roman silver smelting and lead pipes. According to a recent study, however, lead is a much more ancient nemesis, one that predates not just the Romans but the existence of our genus Homo. Paleoanthropologist Renaud Joannes-Boyau of Australia’s Southern Cross University and his colleagues found evidence of exposure to dangerous amounts of lead in the teeth of fossil apes and hominins dating back almost 2 million years. And somewhat controversially, they suggest that the toxic element’s pervasiveness may have helped shape our evolutionary history.

The skull of an early hominid. Credit: Einsamer Schütze / Wikimedia

The Romans didn’t invent lead poisoning

Joannes-Boyau and his colleagues took tiny samples of preserved enamel and dentin from the teeth of 51 fossils. In most of those teeth, the paleoanthropologists found evidence that these apes and hominins had been exposed to lead—sometimes in dangerous quantities—fairly often during their early years.

Tooth enamel forms in thin layers, a little like tree rings, during the first six or so years of a person’s life. The teeth in your mouth right now (and of which you are now uncomfortably aware; you’re welcome) are a chemical and physical record of your childhood health—including, perhaps, whether you liked to snack on lead paint chips. Bands of lead-tainted tooth enamel suggest that a person had a lot of lead in their bloodstream during the year that layer of enamel was forming (in this case, “a lot” means an amount measurable in parts per million).

In 71 percent of the hominin teeth that Joannes-Boyau and his colleagues sampled, dark bands of lead in the tooth enamel showed “clear signs of episodic lead exposure” during the crucial early childhood years. Those included teeth from 100,000-year-old members of our own species found in China and 250,000-year-old French Neanderthals. They also included much earlier hominins who lived between 1 and 2 million years ago in South Africa: early members of our genus Homo, along with our relatives Australopithecus africanus and Paranthropus robustus. Lead exposure, it turns out, is a very ancient problem.

Living in a dangerous world

This study isn’t the first evidence that ancient hominins dealt with lead in their environments. Two Neanderthals living 250,000 years ago in France experienced lead exposure as young children, according to a 2018 study. At the time, they were the oldest known examples of lead exposure (and they’re included in Joannes-Boyau and his colleagues’ recent study).

Until a few thousand years ago, no one was smelting silver, plumbing bathhouses, or releasing lead fumes in car exhaust. So how were our hominin ancestors exposed to the toxic element? Another study, published in 2015, showed that the Spanish caves occupied by other groups of Neanderthals contained enough heavy metals, including lead, to “meet the present-day standards of ‘contaminated soil.’”

Today, we mostly think of lead in terms of human-made pollution, so it’s easy to forget that it’s also found naturally in bedrock and soil. If that weren’t the case, archaeologists couldn’t use lead isotope ratios to tell where certain artifacts were made. And some places—and some types of rock—have higher lead concentrations than others. Several common minerals contain lead compounds, including galena or lead sulfide. And the kind of lead exposure documented in Joannes-Boyau and his colleagues’ study would have happened at an age when little hominins were very prone to putting rocks, cave dirt, and other random objects in their mouths.

Some of the fossils from the Queque cave system in China, which included a 1.8 million-year-old extinct gorilla-like ape called Gigantopithecus blacki, had lead levels higher than 50 parts per million, which Joannes-Boyau and his colleagues describe as “a substantial level of lead that could have triggered some developmental, health, and perhaps social impairments.”

Even for ancient hominins who weren’t living in caves full of lead-rich minerals, wildfires, or volcanic eruptions can also release lead particles into the air, and erosion or flooding can sweep buried lead-rich rock or sediment into water sources. If you’re an Australopithecine living upstream of a lead-rich mica outcropping, for example, erosion might sprinkle poison into your drinking water—or the drinking water of the gazelle you eat or the root system of the bush you get those tasty berries from… .

Our world is full of poisons. Modern humans may have made a habit of digging them up and pumping them into the air, but they’ve always been lying in wait for the unwary.

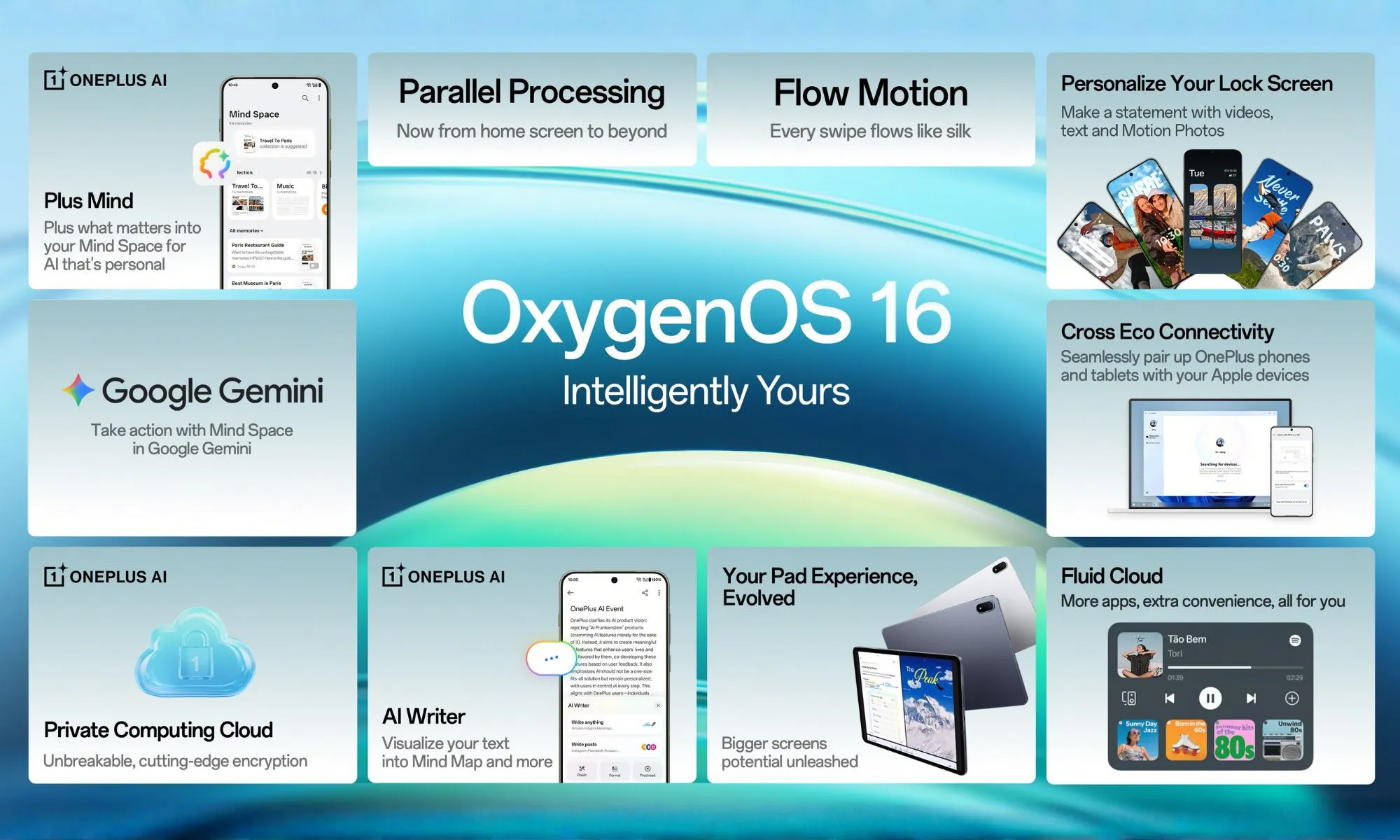

Cubic crystals of the lead-sulfide mineral galena.

Digging into the details

Joannes-Boyau and his colleagues sampled the teeth of several hominin species from South Africa, all unearthed from cave systems just a few kilometers apart. All of them walked the area known as Cradle of Humankind within a few hundred thousand years of each other (at most), and they would have shared a very similar environment. But they also would have had very different diets and ways of life, and that’s reflected in their wildly different exposures to lead.

A. africanus had the highest exposure levels, while P. robustus had signs of infrequent, very slight exposures (with Homo somewhere in between the two). Joannes-Boyau and his colleagues chalk the difference up to the species’ different diets and ecological niches.

“The different patterns of lead exposure could suggest that P. robustus lead bands were the result of acute exposure (e.g., wild forest fire),” Joannes-Boyau and his colleagues wrote, “while for the other two species, known to have a more varied diet, lead bands may be due to more frequent, seasonal, and higher lead concentration through bioaccumulation processes in the food chain.”

Did lead exposure affect our evolution?

Given their evidence that humans and their ancestors have regularly been exposed to lead, the team looked into whether this might have influenced human evolution. In doing so, they focused on a gene called NOVA1, which has been linked to both brain development and the response to lead exposure. The results were quite a bit short of decisive; you can think of things as remaining within the realm of a provocative hypothesis.

The NOVA1 gene encodes a protein that influences the processing of messenger RNAs, allowing it to control the production of closely related variants of a single gene. It’s notable for a number of reasons. One is its role in brain development; mice without a working copy of NOVA1 die shortly after birth due to defects in muscle control. Its activity is also altered following exposure to lead.

But perhaps its most interesting feature is that modern humans have a version of the gene that differs by a single amino acid from the version found in all other primates, including our closest relatives, the Denisovans and Neanderthals. This raises the prospect that the difference is significant from an evolutionary perspective. Altering the mouse version so that it is identical to the one found in modern humans does alter the vocal behavior of these mice.

But work with human stem cells has produced mixed results. One group, led by one of the researchers involved in this work, suggested that stem cells carrying the ancestral form of the protein behaved differently from those carrying the modern human version. But others have been unable to replicate those results.

Regardless of that bit of confusion, the researchers used the same system, culturing stem cells with the modern human and ancestral versions of the protein. These clusters of cells (called organoids) were grown in media containing two different concentrations of lead, and changes in gene activity and protein production were examined. The researchers found changes, but the significance isn’t entirely clear. There were differences between the cells with the two versions of the gene, even without any lead present. Adding lead could produce additional changes, but some of those were partially reversed if more lead was added. And none of those changes were clearly related either to a response to lead or the developmental defects it can produce.

The relevance of these changes isn’t obvious, either, as stem cell cultures tend to reflect early neural development while the lead exposure found in the fossilized remains is due to exposure during the first few years of life.

So there isn’t any clear evidence that the variant found in modern humans protects individuals who are exposed to lead, much less that it was selected by evolution for that function. And given the widespread exposure seen in this work, it seems like all of our relatives—including some we know modern humans interbred with—would also have benefited from this variant if it was protective.

Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adr1524 (About DOIs).

Lead poisoning has been a feature of our evolution Read More »