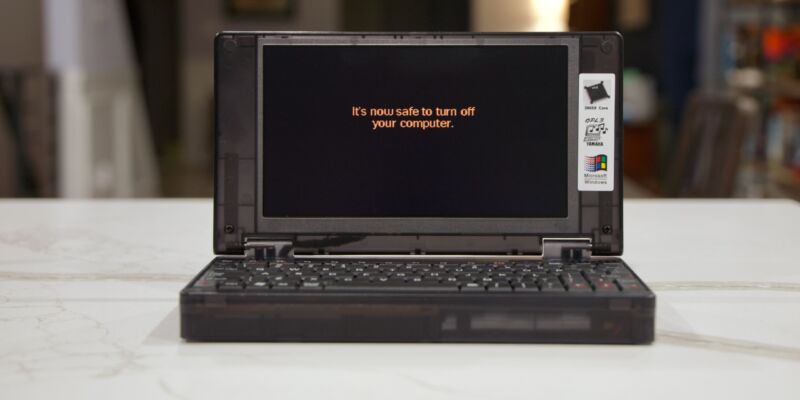

Enlarge / The Pocket 386 is fun for a while, but the shortcomings and the broken stuff start to wear on you after a while.

Andrew Cunningham

The Book 8088 was a neat experiment, but as a clone of the original IBM PC, it was pretty limited in what it could do. Early MS-DOS apps and games worked fine, and the very first Windows versions ran… technically. Just not the later ones that could actually run Windows software.

The Pocket 386 laptop is a lot like the Book 8088, but fast-forwarded to the next huge evolution in the PC’s development. Intel’s 80386 processors not only jumped from 16-bit operation to 32-bit, but they implemented different memory modes that could take advantage of many megabytes of memory while maintaining compatibility with apps that only recognized the first 640KB.

Expanded software compatibility makes this one more appealing to retro-computing enthusiasts since (like a vintage 386) it will do just about everything an 8088 can do, with the added benefit of a whole lot more speed and much better compatibility with seminal versions of Windows. It’s much more convenient to have all this hardware squeezed into a little laptop than in a big, clunky vintage desktop with slowly dying capacitors in it.

But as with the Book 8088, there are implementation problems. Some of them are dealbreakers. The Pocket 386 is still an interesting curio, but some of what’s broken makes it too unreliable and frustrating to really be usable as a vintage system once the novelty wears off.

The 80386

Enlarge / A close-up of the Pocket 386’s tiny keyboard.

Andrew Cunningham

When we talked about the Book 8088, most of our discussion revolved around a single PC: the 1981 IBM PC 5150, the original machine from which a wave of “IBM compatibles” and the modern PC industry sprung. Restricted to 1MB of RAM and 16-bit applications—most of which could only access the first 640KB of memory—the limits of an 8088-based PC mean there are only so many operating systems and applications you can realistically run.

The 80386 is seven years newer than the original 8086, and it’s capable of a whole lot more. The CPU came with many upgrades over the 8086 and 80286, but there are three that are particularly relevant for us: for one, it’s a 32-bit processor capable of addressing up to 4GB of RAM (strictly in theory, for vintage software). It introduced a much-improved “protected mode” that allowed for improved multitasking and the use of virtual memory. And it also included a so-called virtual 8086 mode, which could run multiple “real mode” MS-DOS applications simultaneously from within an operating system running in protected mode.

The result is a chip that is backward-compatible with the vast majority of software that could run on an 8088- or 8086-based PC—notwithstanding certain games or apps written specifically for the old IBM PC’s 4.77 MHz clock speed or other quirks particular to its hardware—but with the power necessary to credibly run some operating systems with graphical user interfaces.

Moving on to the Pocket 386’s specific implementation of the CPU, this is an 80386SX, the weaker of the two 386 variants. You might recall that the Intel 8088 CPU was still a 16-bit processor internally, but it used an 8-bit external bus to cut down on costs, retaining software compatibility with the 8086 but reducing the speed of communication between the CPU and other components in the system. The 386SX is the same way—like the more powerful 80386DX, it remained a 32-bit processor internally, capable of running 32-bit software. But it was connected to the rest of the system by a 16-bit external bus, which limited its performance. The amount of RAM it could address was also limited to 16MB.

(This DX/SX split is the source of some confusion; in the 486 generation, the DX suffix was used to denote a chip with a built-in floating-point unit, while 486SX processors didn’t include one. Both 386 variants still required a separate FPU for people who wanted one, the Intel 80387.)

While the Book 8088 uses vintage PC processors (usually a NEC V20, a pin-compatible 8088 upgrade), the Pocket 386 is using a slightly different version of the 80386SX core that wouldn’t have appeared in actual consumer PCs. Manufactured by a company called Ali, the M6117C is a late-’90s version of the 386SX core combined with a chipset intended for embedded systems rather than consumer PCs.